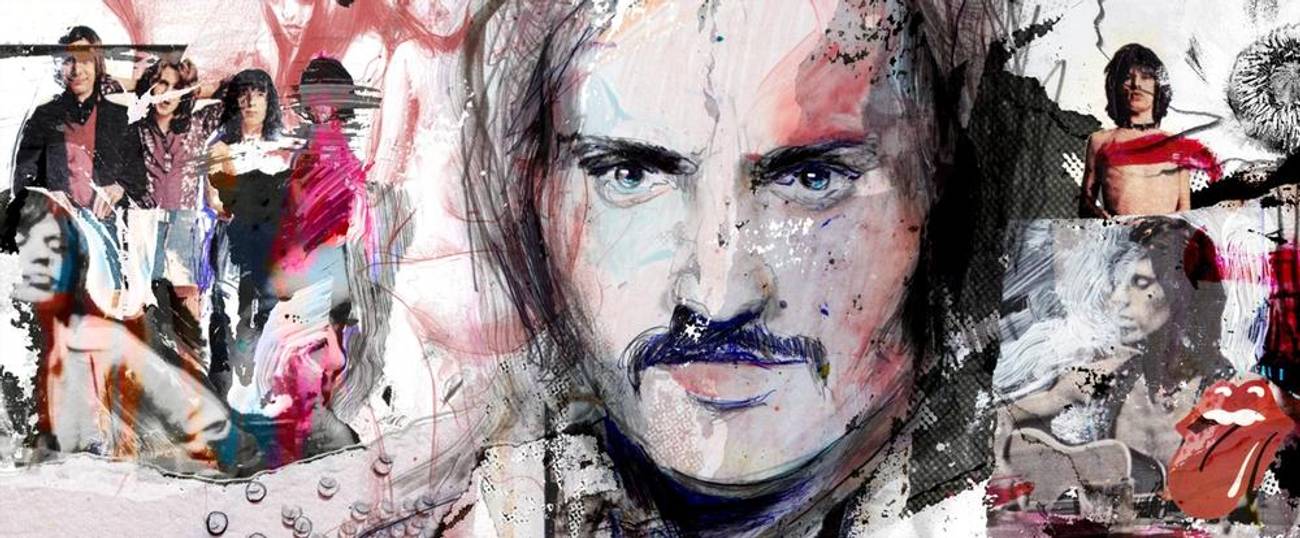

Mr. Jimmy

A tribute to my brother Jimmy Miller, who produced the Rolling Stones’ greatest records and heard the music in everything around him, on the 25th anniversary of his death

“Nothing lasts, except the music.” Jimmy Miller was deep into a hash-induced soliloquy about life, love, loss, and music, contemplating the fleeting nature of fame, as we walked to Olympic Studios on a cold, wet night in London. It was the harsh winter of 1968 following the legendary Summer of Love. My elder half-brother had already become a musical force in London, but it hadn’t fazed him. He was 26; I was 20.

We had all drunk too much at an Indian restaurant near the Olympic, one of the London’s first independent studios where Jimmy was producing what would become one of the Rolling Stones’ and rock’s most iconic albums: Beggars Banquet. He needed to get some air before the session began, he said. He needed to clear his head and find a groove. So we walked, and talked.

An occasional graduate student at the London School of Economics, I far preferred hanging out with Jimmy to my classes. I loved watching him create music from midnight to dawn. Jimmy had just started to produce records for the Rolling Stones when I arrived in London, the center of the ’60s music revolution. Working with the Stones was thrilling, he told me. Though Jimmy’s musical life had started at age 8 playing the drums, writing music and crooning, he had discovered early on that producing records—helping a band create a vibe and an original sound—was what truly inspired him. Addicted to all forms of American music—R&B, gospel, jazz, rock, and folk music—he found it ironic that he had finally found his place in London.

He loved working with great musicians, and there had already been a string of them. Having produced his first record in 1963, Jimmy began working for young New York and Jersey-based groups. After hearing some of his early work, especially “Incense” by The Anglos, Chris Blackwell of Island Records invited him to London to work with younger artists, among them, the mega-talented Steve Winwood, then still a teenager and part of the Spencer Davis Group. The group’s breakthrough single, “Gimme Some Lovin’,” whose driving beat made it a megahit in 1966, had put Winwood, the band, and my brother on rock music’s map. Their place was strengthened by their next hit a year later—“I’m a Man”—which Jimmy co-wrote with Winwood. A bond between them was growing.

Jimmy had quickly sensed that Winwood was a far greater talent than the group itself. When Winwood broke away to form his own group, Traffic, Jimmy began producing their albums, too, including what became a rock classic and still among my all-time favorites, Mr. Fantasy.

Jimmy never seemed to rest. While he was producing records with Traffic, he also worked with Traffic guitarist Dave Mason on Family’s debut album, Music in a Doll’s House. That disc, too, was an instant hit that established the group as among the most original in progressive rock. He also helped keyboard player Gary Wright assemble a new group for Island Records, Spooky Tooth.

Then Mick Jagger came calling. Jimmy had been recording Traffic in Olympic’s Studio B while the Stones were working on their own ill-fated psychedelic offering in Studio A. One night, Jagger dropped by Jimmy’s studio at the suggestion of the Stones’ recording engineer, Glyn Johns, to watch my brother work and get a sense of his musical direction. He must have been impressed with what he saw and heard, for soon after Jagger asked Jimmy to produce a song.

A longtime Stones fan, Jimmy was elated by the offer, though he knew it was a rescue mission of sorts. The mid-1960s had not been kind to the group. The Beatles were all the rage, and the Stones had tried to imitate their Sgt. Pepper sound on the self-produced Their Satanic Majesties Request, losing their own trademark R&B vibe in the process. The album bombed. Critics and fans alike were questioning the band’s direction and whether it even had a future. “We’d run out of gas,” Keith Richards, the Stones’ co-founder, acknowledged in his absorbing memoir, Life.

Friends were showering Mick Jagger with unsolicited, contradictory advice about what to record next. Jimmy, too, had a view, which he gently but firmly shared with Jagger as they began working together: Stick to your roots, he told him. Be who you are. It was the advice he gave everyone he loved.

Jimmy remained true to his own American musical and cultural roots. While many American émigrés to London adopted annoying faux English accents, Jimmy proudly kept his vowels broad and a drawer full of faded jeans. His sole concession to the English fashion then captivating America and much of the world were a pair of cowboy boots he had handmade in Chelsea.

Richards describes their first session together in Life. “We turned up at Olympic Studios and said, we’ll have run-through and see how things go,” Richards recalled. “We just played—anything. We weren’t trying to make a track that day. We were feeling the room, feeling Jimmy out; and Jimmy was feeling us out. … All I remember is having a very, very good feeling about him when we left the session, about twelve hours later.”

Jimmy’s regard for the group, and especially Keith Richards, was mutual. Their initial collaboration resulted in rock ’n’ roll magic, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” a song whose lyrics were inspired, quite literally, by the sound of a gardener’s rubber boots stomping through mud outside Keith’s cottage at Redlands where they had been up all night. Jagger had been awakened by the splash of Jack Dyer’s galoshes. “What’s that?” Mick had asked. “Oh, that’s Jack,” Richards had replied. “Jumping Jack.” The rest is rock history.

Jimmy’s six-year collaboration with the Stones resulted in what many critics regard as the most fruitful in rock history. Writing in Rolling Stone in May 2018, reporter/critic Jim Merlis called Jimmy’s five albums with the Stones—Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main Street, Goats Head Soup—not only the Stones’ best work, but four of the “greatest rock albums of all time.” (I would probably not include Goats Head Soup in that list.)

Merlis wrote that my brother had brought out the best in the band in two ways. First, Jimmy had encouraged experimentation. When the band played the demo for “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” on a mono cassette, for instance, and Richards said how much he liked the distorted sound of his acoustic guitar overloading the tape, Jimmy suggested that they record the guitar part that way.

My brother also brought a groove. Because he was what Richards called such a “damn good drummer,” Jimmy inherently “understood groove.” He made it easy for Richards to “set the groove and the tempos.” “Sympathy for the Devil,” a perfect blend of sensuous rhythm and dark lyrics that had started as a folk-inspired dirge, would have been “nothing without the samba rhythm, which was incorporated under Miller’s watch,” Keith Richards wrote.

My own memory of those magical nights at Olympic with Jimmy and the Stones are shrouded in stoned nostalgia. There are snippets of images—Keith Richards doing solo riffs on his guitar—those “crucial, wonderful riffs that just came, I don’t know where from,” he would write—or Jagger pacing the room, lithe and pencil-thin, leopard-like, waiting to pounce on a new tune or lyric, his then-girlfriend and muse Marianne Faithfull floating thru the studio, a vision in white: long platinum hair, a white dress, white boots.

What also remains indelible is the memory of Jimmy’s quiet, but boundless energy, his infectious enthusiasm for the music, and his inability to stay put. When Jimmy had an idea, he would abandon the giant console where tracks were mixed and ignore the glass wall separating him and the engineer from the band. Suddenly he would appear in the studio, adding percussion to a Stones riff, singing along with them in harmony, or injecting an original sound to a track—that touch of Miller-ian genius—a washboard, a whistle, a flute, a tambourine, finger cymbals, congas, castanets, two Coke bottles, and my favorite, the stuff of rock production legend, the celebrated cowbell that opened the Stones’ classic “Honky Tonk Women.”

He was not a micromanager. Nor did he try to impose his musical vision on a band. Jimmy just heard the unheard music in everything around him, and urged bands to harness it. His innovations were often small–accelerating a tempo or a shift in percussion, and sometimes major—supporting Mick and Keith’s idea of using the London Bach Choir in an English gospel version of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (with its shout-out to Mr. Jimmy in the middle), promoting the haunting gospel backing vocals in the Jimmy Reed-inspired “Gimme Shelter,” and switching to a samba rhythm in “Sympathy for the Devil.”

For Jimmy, it was always about the band and the music, not about politics or the brutal, polarizing Vietnam War that had shattered the nation’s unity, sense of global mission, and moral aspirations. I had left New York to avoid jail for my protest activities. Jimmy had migrated for the music. He almost always underplayed his role as conductor, musician, and mentor. He told one reviewer asking about his contribution to the Stones’ comeback hit “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” for instance, that the song had been written long before he had joined them. When the gifted Stones’ drummer Charlie Watts didn’t feel a rhythm figure that Jimmy had played and everyone liked, Jimmy recalled in an anecdote attributed to Richard Buskin’s Inside Tracks, “Charlie, who was lovely and humble said, ‘Jim, that sounds great, you play it.’”

Watts was effusive about my brother’s role. He told a writer in According to the Rolling Stones that Jimmy had “made me stop and think again about the way I play drums in the studio. And I became a much better drummer in the studio thanks to him. Together we made some of the best records we’ve ever made.” Last month on Steve Jordan’s radio show, “Layin’ It Down,” Watts said that my brother was not only a terrific drummer, “in a studio,” he said, “he was funky,”

In 1968, Jimmy produced Traffic’s second studio offering. His work sparkles on the ethereal “Forty Thousand Headmen” and the staple jam, “Feelin’ Alright.” He brought his amazing touch to Blind Faith, one of the first “supergroups,” which assembled Winwood, Eric Clapton, then with Cream, Ginger Baker, the gifted drummer who recently died, and Rick Grech. The band dissolved soon after its American tour. But Jimmy kept producing albums with the individual members of Blind Faith: Ginger Baker’s Air Force in 1970 and Delaney & Bonnie on Tour, with Eric Clapton. In 1971, he helped produce Refugee, an album by The Savage Rose, the Danish progressive rock band, that was heavily influenced by Jimmy’s love of blues and gospel.

Years later, Eddie Kramer, Jimmy’s protégé and his favorite recording engineer, told Blair Jackson with Mix magazine that my brother knew just how to bring musicians together, rehearse them till the sound was right, and excite them about their work. Jimmy was “unstoppable,” he said. He was a “true musical impresario.”

***

Jimmy would have loved being called an “impresario,” since that’s how our father billed himself. Bill Miller, Jewish and Russian-born, one of those self-made Americans, began his musical life as a vaudeville “hoofer.” He, too, had quickly migrated to management and production, where he worked with some of the greatest artists of his generation.

A nightclub owner and the booker of shows for Las Vegas showrooms, our father took pride in the talent he had discovered, nurtured, and promoted. The list was impressive. At the Riviera nightclub in Fort Lee, New Jersey, a stunning art deco theater/restaurant with a retractable roof overlooking the Hudson, he had promoted some of the era’s great entertainers—Jerry Lewis, Frank Sinatra, the “Tony’s,” as he called them (Martin and Bennett), Zero Mostel, Joel Grey, Sophie Tucker, Marge Champion, Eddie Fisher, Henny Youngman, and several of the nation’s other best comics. Later in Vegas, he had helped discover Sonny & Cher, engineered a comeback for Marlene Dietrich, and recruited Barbra Streisand as an initial act for the MGM Grand’s gigantic new showroom, then Vegas’ largest.

Jimmy had a view he shared with Jagger as they began working together: Stick to your roots. Be who you are. It was the advice he gave everyone he loved.

Jimmy was my father’s only son—the product of his second, brief marriage—and he hadn’t spent much time with us growing up, since my father had remarried and moved away. Dad’s work usually kept him away from all of us—on the road scouting talent, or throughout the night at his hotels and showrooms, absences that drove my own mother to drink and despair. The Miller offspring seemed to have little priority in Bill Miller’s life. This was especially true of Jimmy, whose mother, Ann Wingate, lived in Brooklyn while we were being raised mainly in Miami Beach and Los Angeles. So I had loved getting to know Jimmy in London. Our mutual passion for music and all forms of entertainment was a natural bond.

Jimmy never stopped trying to win our father’s attention and approval. Though Dad had tried to discourage his son from show business, music was in his blood. A faded clip from a Reno, Nevada, newspaper in May 1961 recounts Jimmy’s triumphant impromptu stand-in for an opening act at the Riverside Hotel showroom. When the headline singer got laryngitis and couldn’t perform on opening night, Jimmy, who had been rehearsing one of his own songs in a nearby dressing room, was asked to perform in her stead. He won standing ovations and “3 encores,” the paper reported.

At least one member of the audience was ambivalent about his performance, however. Our father, who owned the Riverside, watched him perform that night. While impressed by his son’s obvious talent, he was distressed to see that Jimmy clearly preferred entertaining to attending the law classes my father was paying for in Miami. Eventually, however, even Big Bill, as we called him, accepted the inevitable and took pride in Jimmy’s success.

Jimmy’s wild, productive years with the Stones were destined not to last. The magic, like fame, faded over time. I sensed it as I listened to the demos Jimmy would send me of songs from Goats Head Soup, their last album together. By then, I was back in the United States, jump-starting my own career in journalism. The Stones were no longer recording at Olympic. First, to avoid British taxes—83% on the highest earners, rising to 98% for investments—the group fled to the south of France, to a spectacular château at the base of Cap Ferrat overlooking Villefrance Bay.

Nellcôte, built around the 1890s by an English banker and eventually bought by Keith Richards, may have been gorgeous, but it was a nightmare as a studio. Recording in the makeshift basement studio proved challenging for Jimmy, and disrupted his normal working rhythms and methods. There were a series of cubicles and no comfortable place to assemble the entire band.

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, Jimmy had also started using heavy drugs. Over time, he and some of the Stones had segued from hash and pills—uppers, downers, and everything in between—to coke and heroin. The band could handle it, for a while, though Richards, after checking himself into a clinic in Switzerland to go cold turkey would eventually write that “the life of a junkie is not recommended to anybody.”

My brother’s susceptibility to hard drugs may have been genetic. Though our father hated drugs—and refused to book performers who openly used them—Jimmy’s mother, like mine, was an alcoholic. I always suspected that he inherently lacked the ability to resist stimulants, be it booze, pills, powders, or potions. I am grateful that my brother’s addiction—and my own terror of needles—saved me from ever trying heroin, which may be too powerful a substance for someone with an inherited family bias toward chemical dependency to handle.

Whether the origins of Jimmy’s addiction were chemical or characterological, the changes in his behavior weren’t hard to spot. The postcards from France became less frequent, and their messages were increasingly incoherent. Even at a distance, I sensed that something had gone wrong. My planned trip to Nellcôte that summer never materialized.

Somehow, Jimmy managed to produce Exile on Main Street. But Richards was increasingly addicted to heroin; Jagger spent most of his time in Paris with his new wife, Bianca. Jimmy was having a harder and harder time battling his own drug-induced demons and holding the band together, finding that magical, elusive groove. He cobbled Exile together by using some earlier tracks and doing a final mix in L.A., where it was easy to cop.

I saw him briefly during the beginning of his personal and professional descent. He acknowledged that he was using. I was horrified. Drugs had destroyed several of my friends in high school and college, victims of the late-1960s political and cultural exuberance. Alcohol was destroying my mother. I had a justified terror of addiction. I recoiled and retreated. Jimmy promised me that he, like Keith, would clean up after the album was finished. Keith Richards did so. My brother did not.

By 1973, Jimmy had gone to Jamaica with the Stones to record what became Goats Head Soup—the last of their collaborations and the least satisfying, he later told me. His drug use increased. Recording sessions were disasters. Richards describes those terrible last days as my brother slowly succumbed to dope and “ended up carving swastikas into the mixing board” as he struggled to complete the album. That was his last work for the band.

“I was turned off by them and myself,” Jimmy would later tell an interviewer. “In a way they made me what I am and then didn’t like what they’d created.”

Nobody forced Jimmy to do drugs, though. The Stones had other habits—like wife/girlfriend swapping and casual sex on tour—that never interested Jimmy. Keith was personally disciplined and resolute enough to actually check himself into rehab in a Swiss clinic, withstand the horrific effects of detox, and kick his habit. Jimmy never did.

***

Jimmy’s separation from the Stones was a musical blow to both of them. Soon after Jimmy stopped producing for them, Stones guitarist Mick Taylor quit the band; the group also dropped the American horn section that Jimmy had adored. “The Stones entered a new era,” music writer Chris Welch wrote for The Independent, “but weak self-produced Eighties albums like Black and Blue and Emotional Rescue showed how much they missed a strong hand at the helm.” While the Stones continued writing hit songs and touring to ever larger audiences and venues, the band never again created the brilliance of the music they produced with my brother at the control board. “To understand Miller’s contribution,” J.P. Gelinas wrote in 2007, “one need only compare the albums Jimmy Miller produced for the Stones with the albums the band has made without him.”

After his relationship with the Stones ended, Jimmy soldiered on, producing for a variety of groups. He could never quit either music or heroin. There were often frantic calls to me late at night, discussions about a new rehab facility he had found, promises to check in after the next album was finished, if only I would lend him some money. What I remember most is the desperation in my older brother’s voice, all the while trying to sound casual.

Those calls from Jimmy were a warning of what drugs, and life, can do to people, including talented people, and people that you love. How could my gifted brother, who had produced lasting work that amazed and delighted millions of listeners, and made a small fortune in the music industry, have permitted himself to become a slave to a stupid drug that would bankrupt him, and destroy his awesome talent and creativity? He lied to his family about seeking treatment, and he undoubtedly spent even more time and effort lying to himself about his willingness and capacity to get off heroin. Every addict is by definition susceptible to addiction. Whatever predispositions we may inherit, we are each the captains of our own ship.

Those encounters with Jimmy during his downward spiral were serially heartbreaking. So were the drug-related losses that followed—the death of his wife, Geraldine, a gorgeous former Playboy hostess whom I adored, and of their son Michael.

But having witnessed the decline or death of friends early on, I knew that the money he was seeking would go straight into his arm, not to a clinic. So I kept saying no whenever he called. My younger sister Susan was more forgiving, or less wised-up. She lent Jimmy money she could ill afford for “rehab,” only to see it squandered. She was at his hospital bed in 1994 in Denver when he died, at age 52, of heroin-related liver failure. Having deliberately distanced myself over the years from him and his struggle with heroin, I was in New York. I still regret that I did not do more to try to help him. A part of me was angry at him, too. I felt like he robbed me of the chance to say goodbye.

Still, I find comfort in the fact that Jimmy continued producing music he loved. In the late 1970s, he produced two superb albums—Overkill and Bomber—for the heavy metal band, Motörhead. He worked on New Hope for the Wretched, a terrific album by the punk band the Plasmatics, and with Primal Scream, a cult rock group whose breakthrough 1991 hit “Movin’ On Up” on its album Screamadelica was heavily influenced by the Stones. Shortly before he died, he had gone to Denver to work with guitarist and songwriter Joey Stec.

On this, the 25th anniversary of his death, there is also comfort in the endurance of the music he helped create—the sound and sensibility of the 1960s which has transcended politics, national borders and ethnic and generational boundaries. I have heard the music that Jimmy helped create with such musical giants as Traffic, Blind Faith, and the Stones nearly every day since his death, in cars, drugstores, supermarkets, health clubs, and in the background of scenes in movies and TV shows. A half-century later, it transmits a unique kind of energy that turns people on. That makes me happy, as it would have made Jimmy happy.

Jimmy wouldn’t have cared that he was never inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, or that few outside music circles know his name or his contribution to rock’s legacy. What mattered, he believed all his life, was the music. Rest in peace, brother.

Judith Miller, Tablet Magazine’s theater critic, is a former New York Times Cairo bureau chief and investigative reporter. She is also the author of the memoir The Story: A Reporter’s Journey.