Mastering the Mechanics of Wealth and Power in ‘A Dual Inheritance’

In Joanna Hershon’s absorbing new novel, a Jew on the margins of American respectability reaches the pinnacle of the class pyramid

The title of Joanna Hershon’s absorbing new novel, A Dual Inheritance, announces its fascination with binary oppositions that are at the same time complementary pairs. Man and woman, parent and child, rich and poor, native and immigrant—all of these clash in Hershon’s story, which has an old-fashioned breadth of scope, spanning 50 years and several continents.

But in each case, she shows, the clash is only one part of a deeper dialectic, by which opposites define and shape one another. How do the rich appreciate their riches unless they come face to face with poverty? What is the child’s rebellion against the parent if not a necessary step on the road to becoming a parent herself? And—to name the opposition that underlies all the others in this novel—how can a Jew discover all the ways he is shaped by Jewishness unless he becomes intimate with a Gentile?

The meeting of Jew and Christian that sets Hershon’s story in motion takes place on the very first page. When Ed Cantowitz and Hugh Shipley run into each other at Harvard in 1962, they are something between archetypes and clichés. We know them before we have met them, because their sociological profiles are so familiar: “Ed was on scholarship and was a rigorous and nakedly ambitious student with a government concentration and a gift for statistics. … Hugh, on the other hand, often smelled like whiskey … and he was, of course, a Shipley, which gave everything he did a kind of simultaneous legitimacy and scandal.”

Ed, in other words, is the scrappy working-class Jew, the son of a steam-fitter, whose brains took him to the Ivy League and who is determined to make the most of the opportunity. Hugh is the handsome, languid WASP, living on the remains of a family fortune, who came to Harvard by right of birth and is just self-aware enough to feel guilty about it. Hershon arranges their first meeting with apt symbolism: Ed comes up behind Hugh and grips him by the arm, forcing his way into Hugh’s line of sight by sheer effrontery.

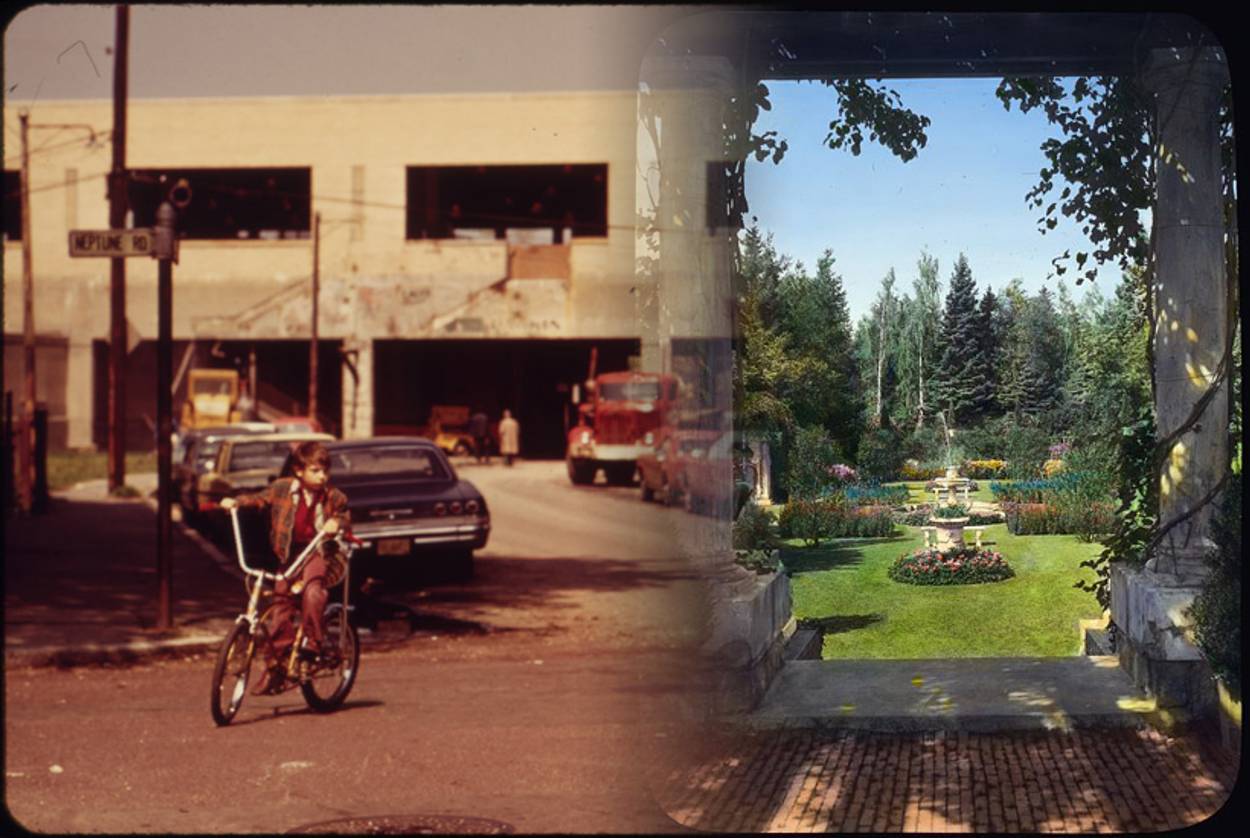

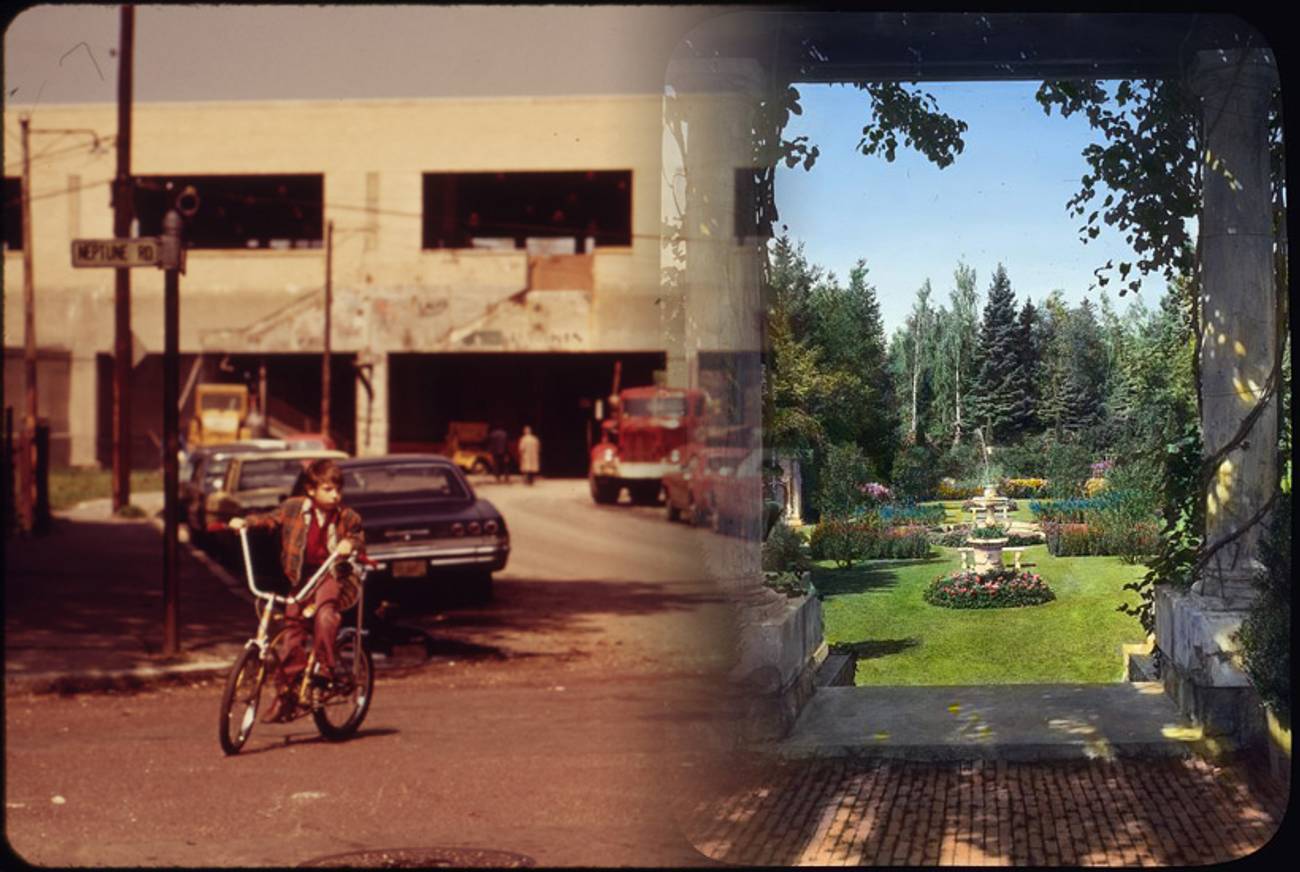

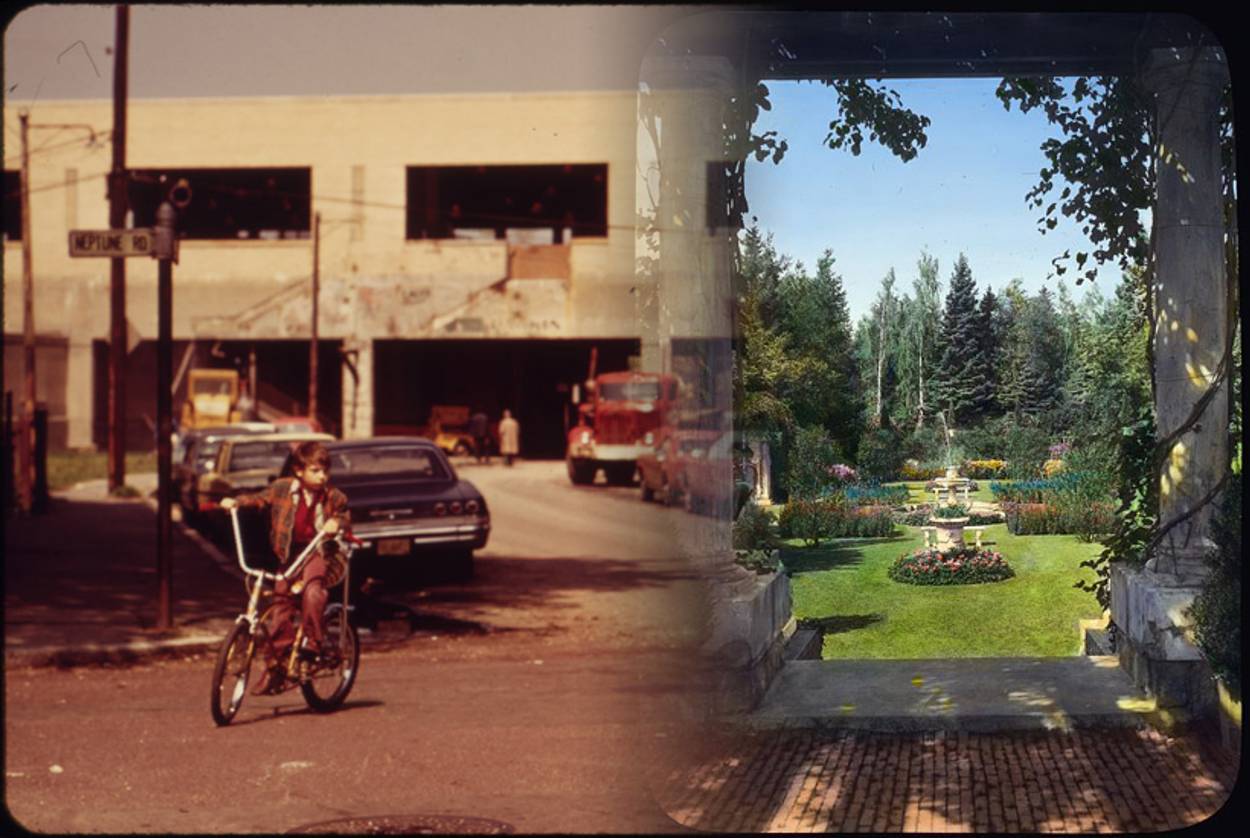

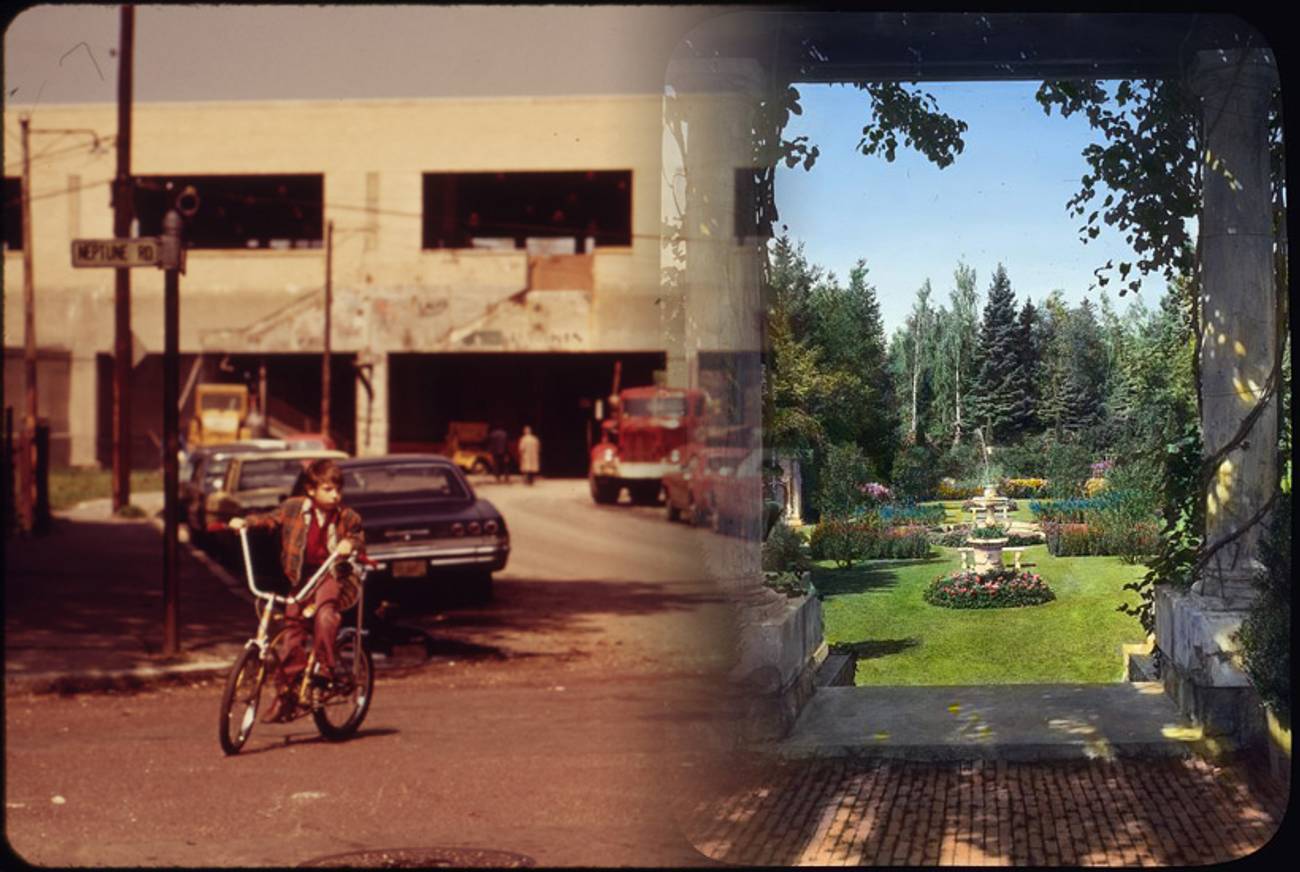

But if class and religion are enough to tell us that Ed and Hugh belong to different species, their individual experiences bring them closer together. Both have lost their mothers and must negotiate relationships with their difficult fathers. When Hugh visits Ed’s childhood home, in the gritty, de-gentrifying Boston neighborhood of Dorchester, he sees everything that Ed is fleeing from: not just poverty or Jewishness, but a father marinated in belligerent self-pity.

Likewise, when Ed accompanies Hugh to the vacation resort of Fishers Island, Maine, he sees the stifling clannishness of the WASP aristocracy, whose hypocrisy has victimized Hugh in a particularly intimate way. As a teenager, we learn early on, Hugh was in love with a fellow-student, Helen, and got her pregnant. But she was spirited away by her family and made to have an abortion, leaving Hugh bewildered and resentful at his seeming abandonment. Only years later do they reunite and try to resume their relationship where they left off.

For all these symmetries, Hershon can’t conceal that the center of the novel’s gravity lies with Ed, not Hugh. This is perhaps inevitable, for strictly novelistic reasons. The social outsider will always be a more compelling protagonist than the insider, because the outsider’s point of view allows the reader to become a spy. Ed at Helen’s family’s house on Fishers Island is like Charles Ryder at Brideshead, discovering a kind of life of which he had never dreamed: yachts, mansions, servants.

At dinner one night, Ed asks Helen’s father to pass the ketchup, only to be amazed when a servant immediately appears bearing ketchup just for him. “He imagined that acquiring a job position in the Ordway household,” Hershon writes, “not only involved extensive hearing examinations and a willingness to press one’s ears against doors but an acute understanding that every desire, no matter how small, no matter how barely articulated, was desire nonetheless.” When he drops his napkin and peers under the table, however, Ed realizes that the servant did not magically anticipate his wish; she was summoned by a concealed electric buzzer. It is a clever metaphor: Wealth and power are not ethereal endowments but mechanisms, which Ed is determined to master.

That determination is enough to impress Helen’s father, who gives Ed a job at his Wall Street firm. Soon enough, and inevitably, he falls in love with Helen herself. She remains a thin character, less a protagonist in her own right than a symbol—for Ed, of upper-class grace; for Hugh, of personal redemption. When this love triangle is resolved in favor of Hugh, Ed is left to nurse a lifelong wound, which eventually shatters Hugh and Ed’s friendship. (It is a nice, comic touch, however, that the excuse for Ed to break with Hugh comes in a disagreement over Israel and the Six Day War—the public masking the private.)

What Hershon manages to show, in this first, scene-setting part of the novel, is that Ed and Hugh, for all their differences, have the same central motivation. Each is fascinated by the tribe to which he does not belong—it’s no accident that Hugh is a student of anthropology—and each wants to flee his family, to create himself anew. For Ed, a Jew on the margins of American respectability, this means getting richer and more conventional. For Hugh, at the pinnacle of the class pyramid, it means getting poorer and more eccentric.

And when the action jumps forward to 1970, we learn that that is exactly what each man has done. Ed starts a Wall Street firm with some Jewish partners, and they turn themselves into rich men. (In another too-perfect development, Ed’s company ends up buying out Helen’s father’s old-WASP firm—a symbolic triumph for Ed and for the Jews of Wall Street.) Meanwhile, Hugh’s guilt over his own privilege leads him to become a humanitarian activist, running medical clinics in Tanzania and, later, Haiti.

But we are still only a few years into what will become a multigenerational story, and Hershon has several tricks up her sleeve. It would be a shame to spoil the coincidences and reversals that will keep the relationship between Ed and Hugh alive. What becomes clear, however, is that Hershon is deeply skeptical of the possibility of genuine rebellion against one’s background. After all, she implies, we can only invent ourselves out of the materials we have to hand, which are the ones we have inherited.

In this way, Hugh’s humanitarian work takes him far from the eastern seaboard and strips him of material luxuries. Yet it can also be read as a grand example of noblesse oblige, the aristocrat’s privilege of doing good. Likewise, Ed’s fortune allows him to move from Dorchester to Park Avenue, where his walls are hung with Rothkos. Yet every token of status he accumulates only fuels the anxiety that drives him and that drives his wife away from him. Such contradictions will increase in the next generation, as Hugh and Ed’s children themselves enact rebellions against their fathers and end up ironically returning to ancestral types.

As Hershon approaches the present, she becomes more adept at capturing the feel of the age, the ways class and privilege manifest themselves in everyday life. In 1962, a Jew at Harvard feels himself to be an outsider. In the 1980s, Ed’s daughter at an elite boarding school is part of a common youth culture, with drugs and music as the great levelers. None of the Jews in Hershon’s story feels the need to deny Jewishness, to convert or pass; the Cantowitzes don’t go to synagogue, but they don’t go to church either. After all, Hershon is writing about a democratizing age, the very time when Jews were making themselves at home in the American upper-middle class. The Jew, A Dual Inheritance reminds us, was once the spy in American society, feeling his way into a society that was still terra incognita. Now that this assimilation is largely accomplished, it is only by looking back, as in a work of historical fiction, that we can remember the pains and pleasures of that kind of exploration.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.