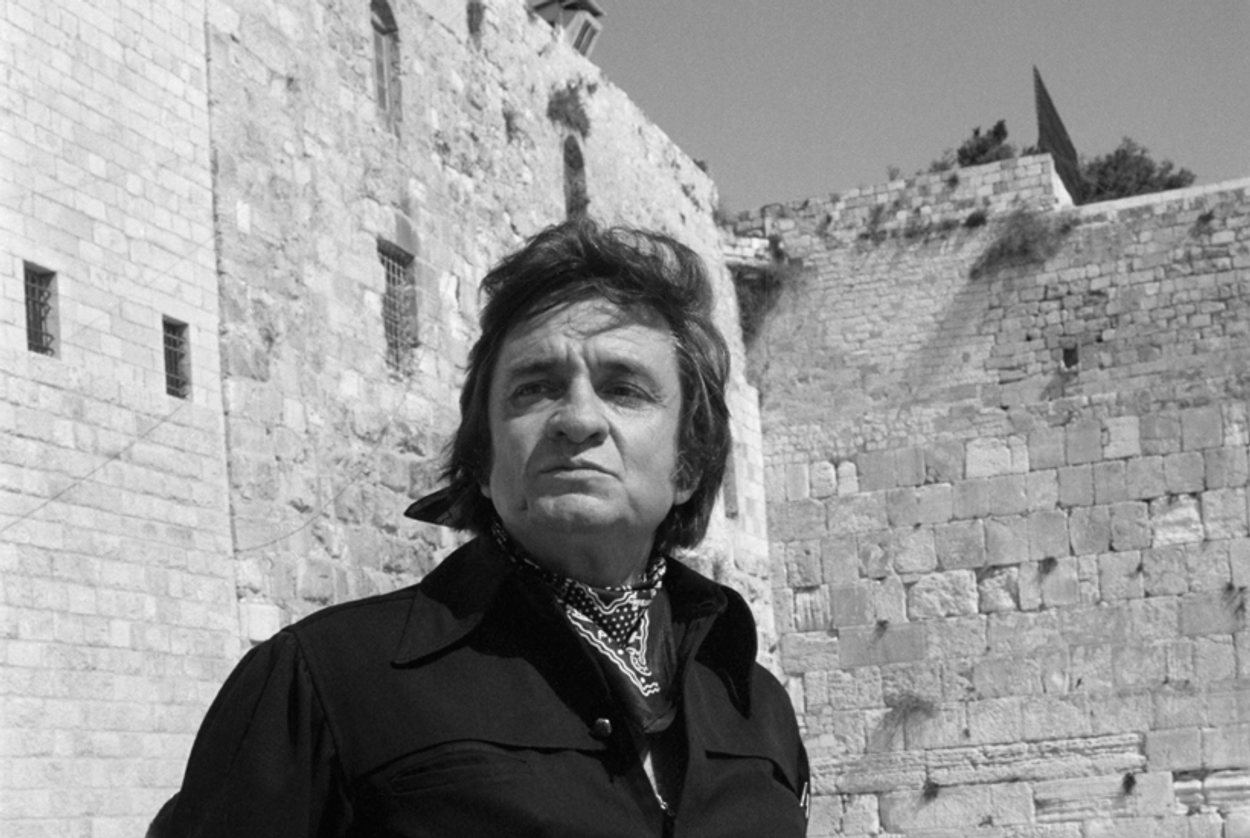

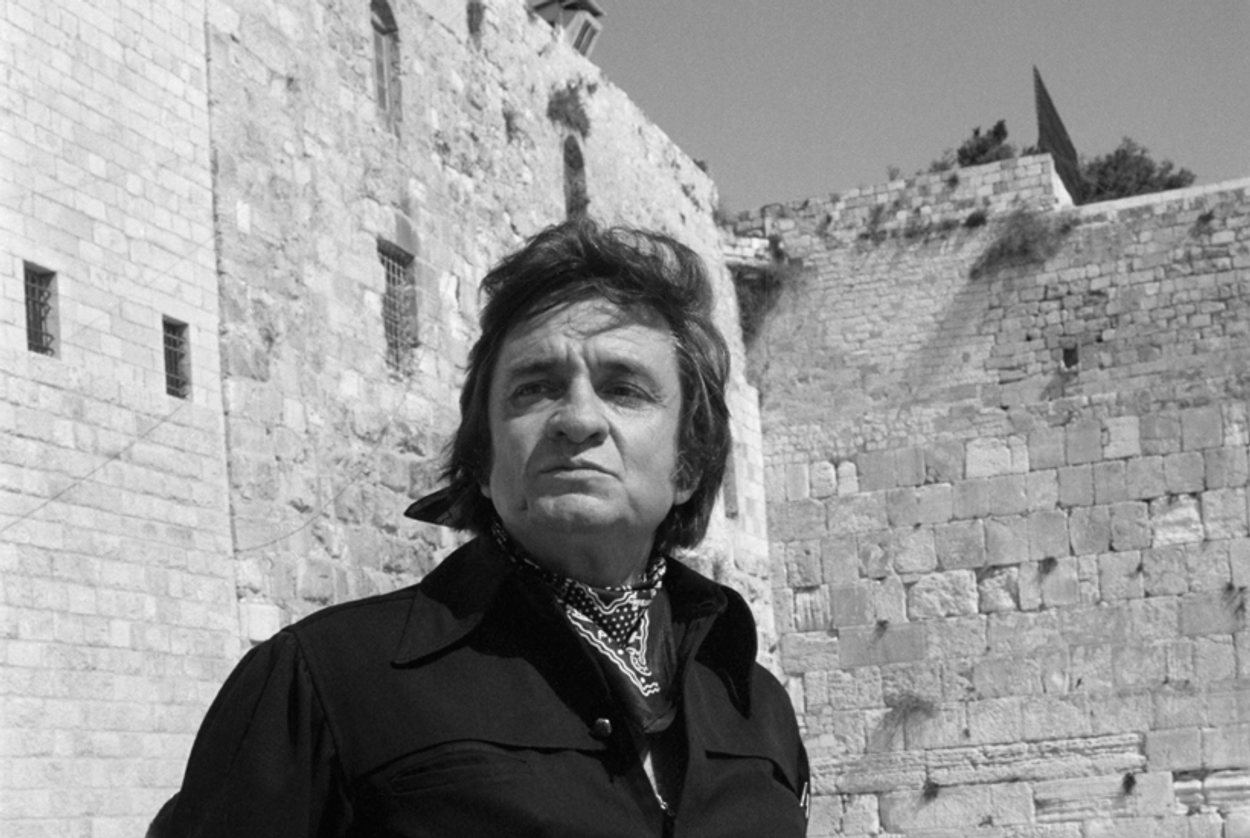

Johnny Cash in the Holy Land

The country singer—and a founding father of American Christian Zionism—died 11 years ago this week

Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash were deeply religious people whose personal and professional lives were imbued with a sense of spiritual struggle and religious engagement. The 2005 biopic Walk the Line was very good at depicting the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll aspect of Cash’s life and art, but, like almost all Hollywood movies, it steers clear of religion in general and of evangelical Protestant religion in particular. Also left out the film was the story of Johnny and June Carter Cash’s passionate engagement with Israel, an engagement that grew out of their religious beliefs. John’s interest in Israel started with a wish to visit the Christian holy sites and “walk where Jesus walked.” Cash’s initial visit to the Israel in 1966 was followed by a trip with June in 1968 and developed into a lifelong project to serve as advocates for the State of Israel, even when such advocacy was unfashionable among American performing artists.

Brought up in a devout Baptist home, Johnny Cash was introduced to music through the local church choir in which his mother sang. She taught Johnny scores of hymns and songs, and it was at age 10, in order to accompany his mother, that he learned to play the guitar. Many decades later, Cash told an interviewer that, of the over 200 albums that he had recorded, his favorite was “My Mother’s Hymn Book,” in which he plays songs that his mother sang in church.

Among those moving songs is “I’m Bound for the Promised Land,” which opens with an evocation of the singer standing on “Jordan’s stormy banks.” For Cash’s mother and the other members of her rural Baptist church in Tennessee, the view from “Jordan’s stormy banks” to “the tranquility of the Promised Land” to which they were bound was a metaphor for the heavenly reward that awaits the righteous when they cross the threshold of death and enter paradise.

“Promised Land” and many other songs that refer to “Canaan,” Jordan, Gilead, and Zion would have all been understood in the 1930s and ’40s as rich metaphors that evoke biblical places in the service of spiritual ideas, a tradition that has deep roots in both the white and black churches. And the promised-land idea informed the thinking of the early American colonists and the Founding Fathers, who spoke of the American experiment as providing a promised land for refugees from the tyranny of the “English Pharaoh,” George III.

But for generations of American, among them the Cash ancestors, Zion, the Promised Land was much more that a metaphor: It was “Jesus’ Land.” In the period after the Civil War many among the American Christian elites flocked there. Steamship travel made it possible to sail from New York, Boston, or Charleston and reach the port of Jaffa in three weeks. Among some American Christians “Zeal for Zion” ran so high that they attempted to create colonies in Palestine. In the second half of the 19th century, before the major era of Zionist settlement, at least four such colonies were founded. Most of them failed, but the American Colony of Jerusalem, co-founded by Swedish Christians, left its mark on Jerusalem.

Many writers on the subject of Christians and Zionism tend to emphasize the “End Time” theology of supporters of Israel. But the long view of American religious and social history reveals that American Christianity, in its many persuasions and denominations, has a very long history of engagement with the idea and reality of Zion. Eleven years after their deaths, Johnny and June Carter Cash stand as exemplars of the complexity and depth of the American connection to both the idea and reality of the promised land.

***

Initially, Johnny Cash’s ties to Israel were more musical than political. The same was true of June Carter, who also grew up with many of the same biblically referenced references and songs, some of them recorded by her family, including her mother Maybelle Carter and related members of the renowned Carter musical family. Gospel songs and hymns remained at the core of June and Johnny Cash’s musical endeavors, though they eventually became icons of what was later dubbed “country” music. In the early 1970s, when Johnny Cash was “reborn” as a Christian, he offered up an unusual form of tithing; every 10th song that he recorded would be a hymn or gospel song.

“Zion” and “Canaan” might have remained only a rich American metaphor. But the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 changed all of that—though the changes in Christian America weren’t immediately apparent. As historian David McCullough noted in his biography of President Harry Truman, most American Christians were enthusiastic about the establishment of the state of Israel, and, in granting diplomatic statehood to Israel just minutes after statehood was declared, Truman was following the will of the American people. For the many Americans who were avidly following world events in the postwar period, the “return of the Jews to their land” was understood as the fulfillment of the biblical promise. To those less devout and less theologically inclined, Israel’s creation may not have been understood as a divine act, but it made sense to many because the metaphor of the promised land was so deeply embedded in American culture and religious thought.

Johnny Cash’s life and career exemplify this biblical understanding of modern history. In the 1960s, Cash became intrigued by the possibility of visiting the Holy Land, and in 1966 at the age of 34, he made the first of many visits (or as he termed them, “pilgrimages”) to Israel. The popular Pentecostal preacher Oral Roberts had been on his first pilgrimage to Israel a few years earlier, and this influenced Cash in his decision to visit the Holy Land and to see the Christian holy sites. It was a brief visit and might have been the singer’s only visit to Israel, but only two years later his religious, personal, and professional lives were to converge in a way that would make Israel the country an abiding focus in his life.

Johnny Cash aficionados are certainly familiar with the performer’s struggles with substance abuse, depression, and the “temptations” of the wilder side of the country music industry. The story told in Cash’s autobiographies, and in Walk the Line, are that Johnny Cash crawled out of his cave (both real and metaphorical) with the help of June Carter Cash, to whom he was married in 1968. What is not as well known (and is not depicted in Walk the Line) is that June insisted that they take their honeymoon in Israel: As June understood Johnny’s destiny, he could only be fully redeemed by being in the Holy Land. June told Johnny of a dream she had in which she saw him standing on a mountain in Galilee preaching to the multitudes with a Bible in his hand. One might say that in June Carter Cash’s view or understanding her new husband could be saved by Jesus only if he were to actually walk in Jesus’ footsteps.

On that 1969 “honeymoon pilgrimage,” Johnny and June recorded an album titled In the Holy Land for Columbia Records. It is a curious but quite effective combination of songs about sacred places in Israel woven together with snippets of sightseeing observations by the Cashes and their Israeli tour guide. East Jerusalem and Bethlehem, areas conquered by the Israelis in the 1967 war, were by 1969 thronged with Christian visitors from Europe and the United States. Johnny and June Carter Cash, like thousands of others, sought to “walk where Jesus walked,” and one can sense their excitement and enthusiasm in the songs and pilgrimage narratives of the In the Holy Land album. Like their close friend Rev. Billy Graham, the Cashes saw Israel’s takeover of Jerusalem as having religious significance. God’s hand could again be seen moving in history.

On a subsequent visit to Israel, Cash and his wife were inspired to make a film set in the biblical landscapes they had described on their Holy Land album. The film, Gospel Road, made in 1971, was a documentary-style narration of the life of Jesus. Cash was the narrator, and June Carter played Mary Magdalene. Though it was a commercial flop on its 1972 release in the United States, Gospel Road, with music by Kris Kristofferson, Cash, and other songwriters, had a long “afterlife” on college campuses in the South and the Midwest. The film, whose screenings were sponsored by Campus Crusade for Christ, was seen by many evangelical Christians in the 1970s and ’80s. The recordings from Folsom Prison and San Quentin had made millions of dollars for Johnny and Columbia Records, while Gospel Road, a religious recording, lost money. As Cash told an interviewer: “My record company would rather I be in prison than in church.”

In the opening moments of Gospel Road, Johnny Cash reenacts his wife’s vision of him preaching to the multitudes in Galilee. We see him on a mountaintop (it is Mount Arbel near the Sea of Galilee) holding a Bible and inviting the film’s viewers to join him in a journey through the Holy Land in the footsteps of Jesus. The film then moves to the retelling of Jesus’ life. But Cash’s introductory remarks serve to remind us that American evangelical enthusiasm for Israel was about Jesus and the history of Christianity, not about the modern Jewish experience—though the Jewish “return to the land” is understood by many Christians as the fulfillment of prophecy. For the hundreds of thousands of Christian pilgrims who visit Israel each year, the Holy Land is primarily a Christian Holy Land and only secondarily a Jewish homeland. For these Christians the state of Israel is significant because of the Bible, not because it is the realization of the ideas of Zionist thinkers like Theodor Herzl.

A few years after Gospel Road was released, Johnny and June returned to Israel. They were joined by their children, who were baptized, like their parents, in the Jordan River. The Cash family visits, and their increasing prominence in the American music industry, brought them to the attention of Israeli government officials, who treated them like visiting royalty and facilitated their travel within the country.

In the mid-1990s, when Israeli cities, and particularly Jerusalem, were attacked by Palestinian suicide bombers, tourism to Israel fell off sharply. The Cashes, now in their sixties, returned to Israel for a fifth visit, and with their own money produced a TV film titled Return to the Holy Land. Throughout the film—a musical travelog through pastoral, bucolic sites associated with the life of Jesus—the Cashes assured their American viewers that Israel was as beautiful and tranquil as ever, and they should not hesitate to visit it soon. There is no mention in the film of the conflict with the Palestinians, nor of any internal debates or dissension within Israel. Despite the changes in Israel, and in world attitudes toward the Jewish state, Johnny and June Carter Cash’s zeal for Zion remained intact.

Johnny Cash’s children, who accompanied them on some of their five pilgrimages to Israel, have in their own ways kept alive the Holy Land legacy of their father. John Carter Cash, who has been supervising the reissues of many of his parents’ recordings, has written about his attachment to Israel, which he visited when he was 13 years old. And in the mid-1990s John’s daughter Roseanne Cash wrote a haunting song titled “Western Wall,” which opens with these evocative lines:

I stand here by the Western Wall,

Baby, look at that wall, standin’ silent an’ tall.

An’ I shove my prayers in the cracks.

Got nothin’ to lose, no-one to answer back.

All these years I’ve brought up for review,

Wasn’t taught this but I learned somethin’ new.

Had to answer a distant call,

At the Western Wall.

Roseanne’s song echoes a song titled “Come to the Wailing Wall” that was recorded 30 years earlier by her father on his In the Holy Land LP:

Bring the lost ones homeward

Lead them to this shore

The city gates are open

Heaven’s blessing o’er

Come to the Wailing Wall.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.