Prostitutes, Thieves—and Vampires

Israeli vampire TV series ‘Juda’ could have been written by I.B. Singer

When David Ben-Gurion reportedly said that Israel would become a normal state once it had its “prostitutes and thieves,” he should have also added “and vampires.” The Israeli series Juda, which premiered in Israel in 2017 and is now streaming on Hulu, is the first full-blown Israeli take on the popular supernatural genre. The Israeli and Jewish aspects are central to its storyline and imagery, which creatively borrows from horror and Gothic traditions—their gore, schlock and all. Israeli critics commended the series for its deliberate embrace of these tropes, which it immerses in Israeli reality and packs in tight with new occult Judaic content. The often comical show has a playful attitude toward its bloody subject and is not so much derivative of it as it is enthralled with it, which makes watching its eight episodes a true guilty pleasure.

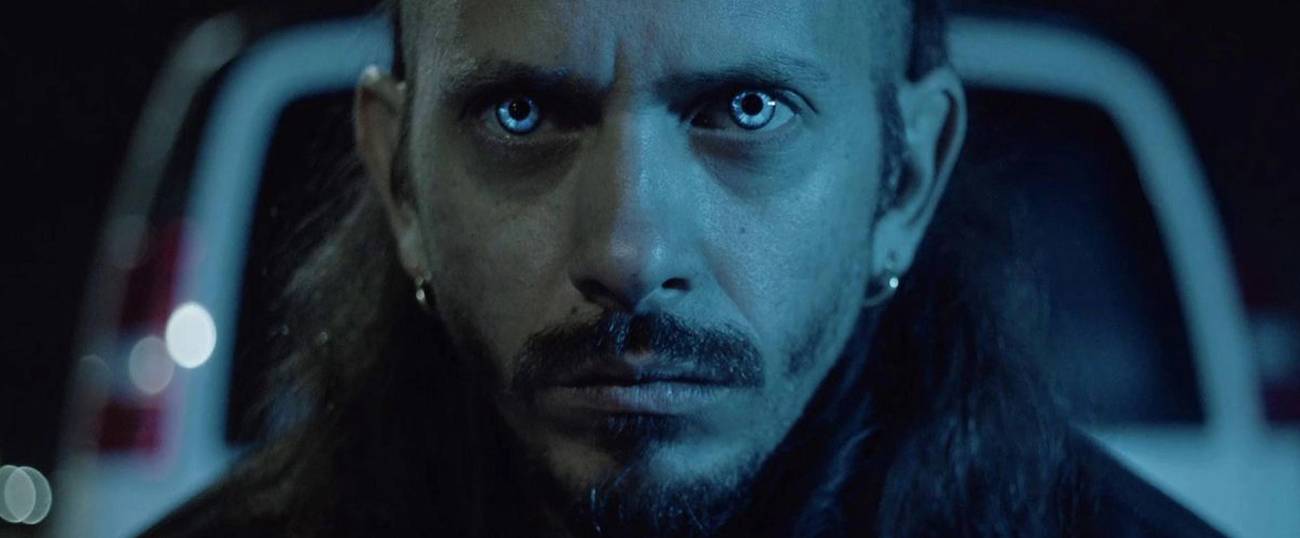

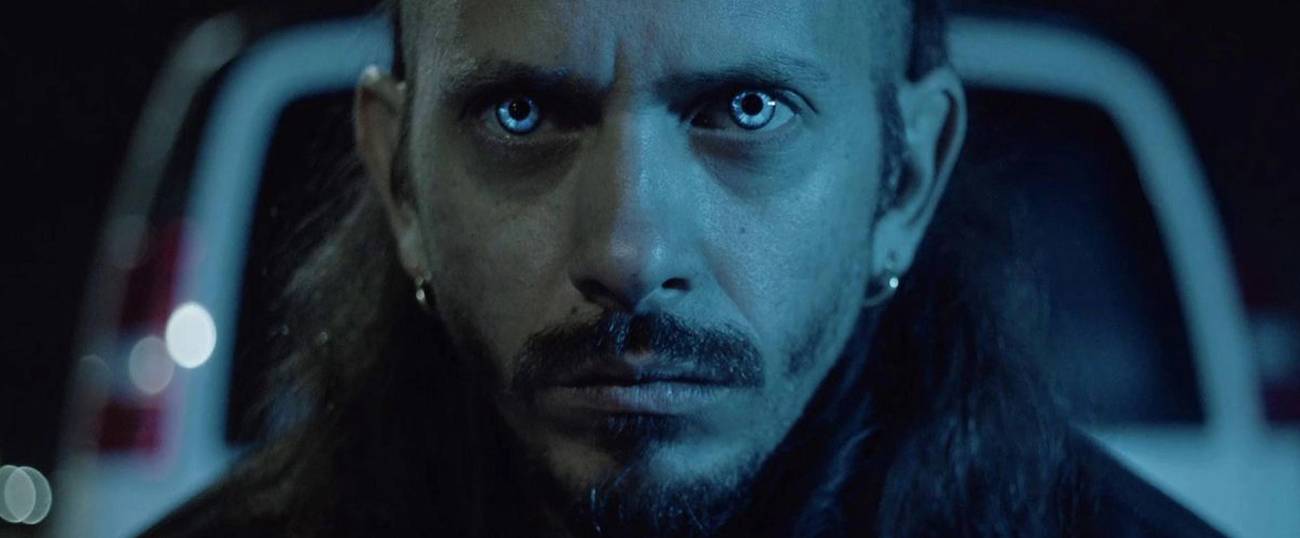

Juda creator and leading star, Israeli actor and director Tzion Baruch, confessed that the show was quite personal for him because it reflected his deep connection to Judaism. Baruch plays Juda, a lowly criminal and gambler in debt to the French Jewish mafia in Israel, who after winning an enormous sum of money at a casino in Romania, is bitten by a stunning vampiress (Anastasia Fein), Dracula’s daughter, whom he mistakes for a prostitute. As expected, the bite transforms him into a vampire, but this is also where the unexpected begins: We learn that the vampires are forbidden from drinking Jewish blood, as it is told that a Jewish vampire will end up vanquishing the entire bloodsucking brood. The rest of the series follows Juda on his return to Israel, where he must deal with his new identity and powers, as well as with the Romanian vampires who come to the Jewish state to find and destroy him before he obliterates them.

Most of the show’s Judaic content is centered on a mysterious rabbi, played by iconic Israeli Yiddish comic Mike Burstyn. The rabbi watches over Juda’s metamorphosis and educates in what it means to be a Jewish vampire: A messianic figure, who, through his beastlike prowess and union with evil, will in fact put an end to vampirism. Instead of relying on actual historical Jewish commentary on vampires, which is present in medieval sources and folklore, Juda freely invents its own Judaic vampire mythos for the 21st century.

There’s a political impetus to Baruch’s vision. As he explains in an interview, he was attracted to the vampire genre precisely because of its anti-Semitic origins, which he wanted to turn on their head in creating an unusual Jewish hero: “The Jewish people were persecuted throughout history, and it’s time for a Jewish superhero.” Baruch’s thinking is certainly linked to the earlier Zionist ethos, but with significant modifications: The superheroes here are not masculine drainers of swamps or sabra-soldiers, but rather a diminutive wisecracking criminal-cum-monster on the run, and an old rabbi who peppers his Hebrew and quotations from holy books with Yiddishisms, and is also a monster-redeemer.

The Israeli present, which Juda lovingly ridicules, is the show’s main setting, but it does not let go of the pre-state Jewish past either: History, particularly the Holocaust, is the key ingredient in this concoction. The series’ most startling section is an animated sequence in the second episode depicting the rabbi’s tale to Juda about a Jewish boy named Dziadek, who escaped the Nazis in a Romanian forest and was saved by none other than Dracula and his son. However, after the boy is found and murdered by the Nazis, Dracula’s son, unable to bear the pain of losing his friend, bites Dziadek and turns him into a vampire. Tragically, Dracula is ultimately forced to kill the boy after learning that a Jewish vampire would eradicate the vampire race. Weeping, he plunges a dagger in Dziadek’s heart and finishes him off—or so we think. What the audience discovers to its shock at the end—forgive the spoiler—is that Dziadek is the rabbi, who did not die, but rather learned to harness his powers and thirst for blood, patiently waiting to fulfill his destiny. Having discovered the truth, Juda asks how he could have survived the war, to which the rabbi responds in typical Jewish fashion with a question: “You still believe that Hitler killed himself?” Thus, the Jewish vampire—a true Jewish superhero—slays the Nazi Amalek and avenges his people.

This revisionist streak is emblematic of how the series approaches the past and its impact on the present. It’s no wonder that Baruch mentions as one of his primary influences Quentin Tarantino, whose Inglourious Basterds (2009) is an irreverent rewriting of the Holocaust with the Jews as unapologetic victors and brutal avengers. Like Dziadek the vampire-rabbi, Tarantino’s Shoshanna (Melanie Laurent) plays a part in the murder of Hitler and his henchmen, putting an end to the Nazi plans.

Yet, with this blurring of lines between the good, the bad, and the ugly, and the idea that in order to defeat evil, one—especially the Jew—must give in to their own dark inclinations, Juda casts a wide pedigree net that goes beyond Tarantino’s cult film. Two sources in particular come to mind: Roman Polanski’s brilliant vampire comedy, Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), and iconic 20th-century Yiddish author Isaac Bashevis Singer. “I.B. Singer could have written it,” I tweeted after finishing the series. Juda echoes Singer and Polanski in its thinking about history—not just how to deal with the past, but how to rewrite it; how to imagine the possibility of Jewish survival in the world where the Jew is perpetually the Other. Unsurprisingly, evil becomes their inevitable main concern and topic of their artistic expression.

***

The Fearless Vampire Killers has aged remarkably well. It still amazes with its cinematographic inventiveness and hilariously bizarre plot twists. Like Juda, it embraces the vampire genre wholesale, playing with its kitsch and gore. The film has been cited for featuring an explicitly Jewish vampire who is unafraid of the cross (the joke about the Yiddish vampire who sniffs at the crucifix, which was recently featured in the currently running HBO series The Outsider, might have been inspired by it), but its Jewishness is much more pervasive and meaningful. Polanski situates his tale in a shtetl lying at the foot of the vampire Count von Krolock’s castle. There are Jews all around, who seem to have come out of the pages of Sholem Aleichem or the Yiddish vaudeville stage: Yoine Shagal the innkeeper (Alfie Bass), who becomes a vampire; his dim-witted domineering wife, Rebecca (Jessie Robins); and his beautiful daughter Sarah, notably played by Sharon Tate, who also turns into a ravishing vampiress. The young nebbish student Alfred, who accompanies professor Abronsius (Jack MacGowran) on his quest to uncover Krolock’s true nature, is suggestively Jewish as well, not least because he is played by Polanski himself.

The Holocaust was never far from Polanski’s mind—his mother died in Auschwitz, while he managed to survive the war in hiding—but it is in this farcical over-the-top comedy that he confronts the memories of his Polish Jewish past for the first time. Polanski described this Jewish subtext in a 1969 interview with the French journal Positif: “In the film there’s an Eastern European culture which was desolated by the Germans and that’s been killed off for good thanks to Polish Stalinism. It’s the kind of thing that you can see in the work of figures like Marc Chagall and Isaac Babel, and also in certain Polish paintings. This culture, which never reappeared after the war, is part of my childhood memories.” Polanski’s sentiment might have been prompted by the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War—the film was released in the United States six months after it—which became a source of pride for many Jews and led to a new anti-Semitic campaign in communist Poland.

Via these childhood memories, Polanski tries to imagine what it would have taken to preserve the destroyed Jewish world. He reimagines evil, embodied in the vampires, as an attractive malevolent force which does not, however, threaten Jewish survival: Both Shagal and his daughter Sarah succumb to and embrace their new nature. At the end of the film, von Krolock lives on, but so does the shtetl. The evil triumphs: Sarah bites Alfred and they ride into the wider world to spread the vampire scourge. The perseverance of evil is a persistent theme in Polanski’s films, but here, to reiterate, the dark forces do not put an end to the Jew. Polanski proposes his own revisionism—a much subtler version than either Tarantino’s or Juda’s: For him, it is as if there never was and never will be a Hitler with his absolute evil, which bitterly and ironically implies that only in a silver screen fairy tale can the Jew endure.

***

In addition to Chagall and Babel as the depictors of Yiddishkeit, Polanski could have also mentioned I.B. Singer, who by 1967 had long become not only the leading Yiddish writer, but a major American Jewish one thanks to the translations of his works into English. Singer consistently revels in the demonic and the macabre, and suffuses his imagination with the awareness of the Holocaust. Though he never portrays the actual events of the war—concentrating either on the remote Jewish past or the postwar present—the Holocaust, similarly to Polanski, is perennially on his mind. His first great Gothic novel, Satan in Goray (1933), which was written in Poland, was already saturated with premonitions of the incoming catastrophe. His Holocaust survivor characters residing in New York resemble the living dead and the vampires. Nevertheless, like in Juda, Singer’s take on evil is playful and wholehearted, though much less blunt and ostentatious than the Israeli series.

In 1943, in the midst of the slaughter raging in Europe, Singer, a refugee in New York, began to write short stories where the protagonist was the Jewish devil. Drawing on the riches of the Yiddish occult, he offered his own intrinsically and indigenously Jewish version of evil as the alternative to the external and eternal hatred of the Jew. For Singer, the Jewish past could only be memorialized via the demonic route; as far as he is concerned, evil is the essential part of what it means to be a human and especially what it means to be an artist. Unlike Juda’s vampire superhero, Singer’s Yiddish devil cannot murder Hitler or rid the world of Dracula, but he can give voice to the Jewish dead and allow Jews to confront morality on the terms of their own horror tales. The beginning of the story “The Last Demon” beautifully and succinctly introduces this point:

I, a demon, bear witness that there are no more demons left. Why demons, when man himself is a demon? Why persuade to evil someone who is already convinced? I am the last of the persuaders. I board in an attic in Tishevitz and draw my sustenance from a Yiddish storybook, a leftover from the days before the great catastrophe. The stories in the book are pablum and duck milk, but the Hebrew letters have a weight of their own. I don’t have to tell you that I am a Jew. What else, a Gentile? I’ve heard that there are Gentile demons, but I don’t know any, nor do I wish to know them. Jacob and Esau don’t become in-laws.

“The stories in the book are pablum and duck milk, but the Hebrew letters have a weight of their own”—this can also be said of Juda. The show’s schlocky entertainment quality does not detract from its Hebrew weightiness—historical, moral, and religious. Its wild mishmash of Jewish lore, the Holocaust, and Israeliness is a testament to the vibrancy of contemporary Israeli culture that looks both outward and inward, as the best of Jewish writers and directors have always done.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marat Grinberg teaches literature and film at Reed College. His forthcoming book is The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf: Culture and Identity Between the Lines (Brandeis University Press).