The Freudian Became a Catholic

Karl Stern, Canadian psychiatrist and writer, was in his day a famous Catholic convert. Why has he been forgotten?

Four years ago, on a January afternoon while Montreal was in the middle of another subarctic deep freeze, I boarded a plane for Munich. Hours before, as the wheels of the taxi spun on the ice and careened toward departures, I realized that I only had one book, Karl Stern’s 1951 memoir The Pillar of Fire, for my flight. I’d found a first edition at a used bookstore, where it cost me the equivalent of two baguettes. It was signed by Stern with a blue fountain pen and addressed in that elegant, unmistakeably European cursive script to a colleague at Montreal’s Saint Mary’s hospital, where he had been psychiatrist-in-chief.

I hadn’t planned on reading it. I’d been reading around Stern, in footnotes and bibliographies, for close to a decade. Every so often, I’d meet an elderly person who remembered him as a Jewish doctor. Others said he was a novelist. Or, a German pianist. My neighbor, a Francophone nun in her eighties, thought he might have been a psychoanalyst for priests. No one ever seemed to be talking about the same man.

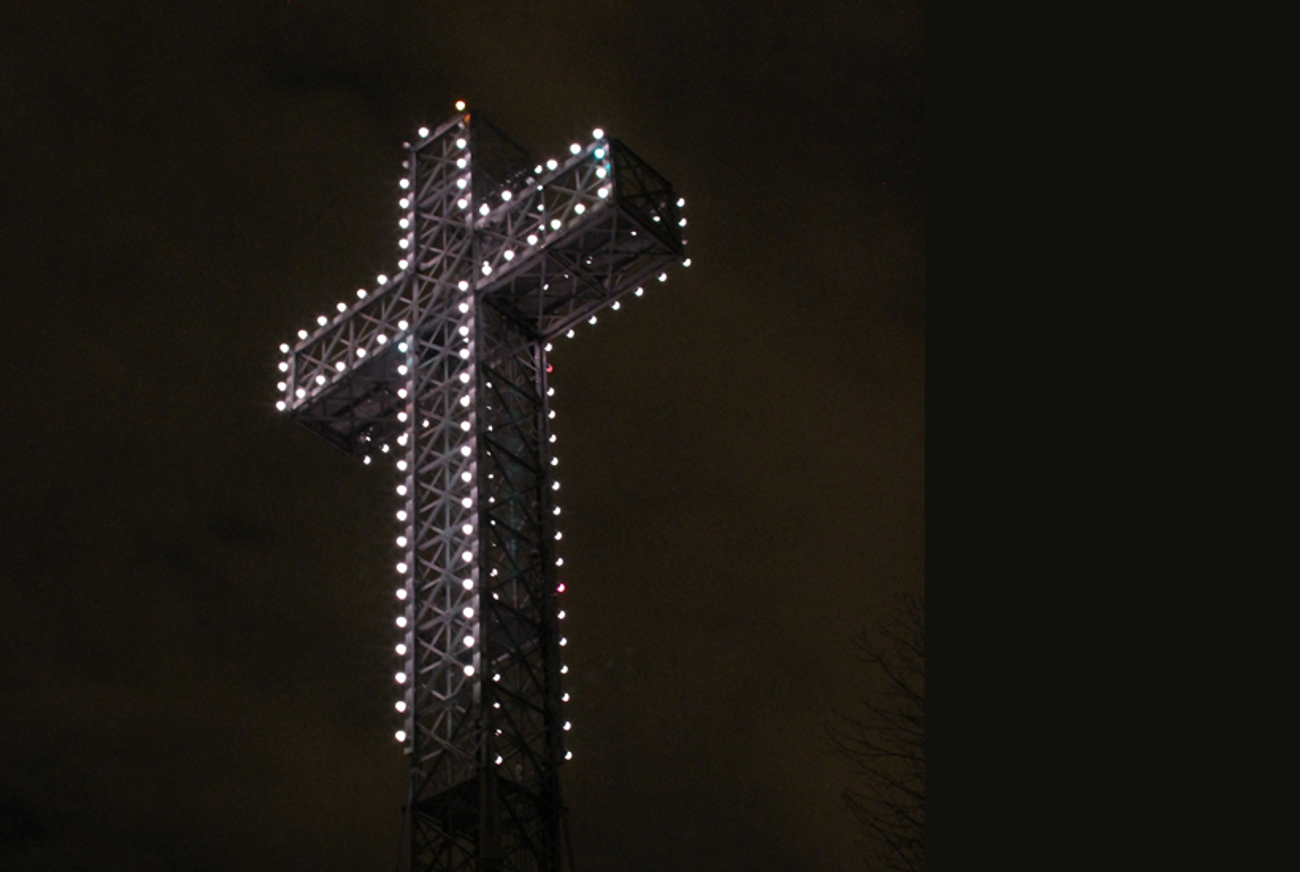

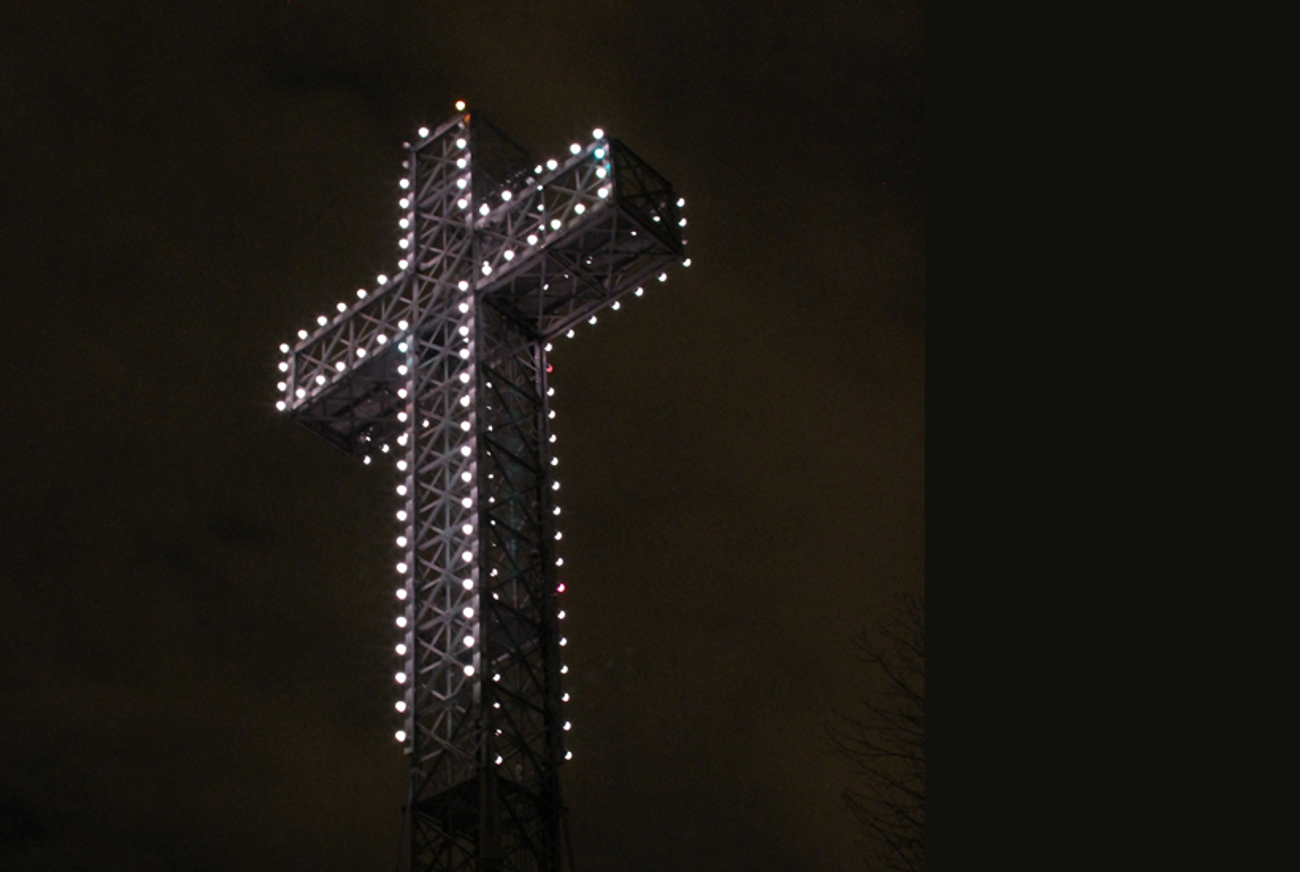

I’d discovered a quotation from The Pillar of Fire in an article about Montreal history by a local scholar, Sherry Simon. Stern, it turns out, was a Bavarian-Jewish refugee, and he recalled looking down at his adoptive city from the mountain at its center. “From the top of Mount Royal,” he writes after his arrival in 1939, “you can almost directly perceive currents of European history of the last few centuries in a petrified form.” I could imagine him at the summit in a continental greatcoat, looking like one of those rootless European émigrés who fill the pages of W.G. Sebald’s novels. Stern would have peered down at the cold-water flats rented by Jewish immigrants on Mordecai Richler’s Saint Urbain street. Then, the French Catholic working-class quartiers further east. He may have turned toward the Anglo-Scottish demesnes in posh Westmount, attempting to situate himself amid the frictions embedded in the cultural genome of this island metropolis. “Thus, the city is parcellated,” he wrote of Montreal’s English, Irish, Jews, French, Catholics, and Protestants, “and everywhere there are frontiers of distrust.”

Who was Stern? Internet searches had turned up little. My plan was, during a European holiday, to donate The Pillar of Fire to Munich’s Jewish museum. It only seemed right: to give it to a place dedicated to a people many of whom scattered to Montreal, London, and Washington Heights, but only if they didn’t perish in Bergen-Belsen or Dachau. I had skimmed the first section and knew that Stern had adored Munich, where he had studied medicine. “With the exception of Paris,” he writes with an ardor usually reserved for descriptions of lovers or great works of art, “there has never been a town which had so much individual expression, so little of the artifact and so much natural growth.”

Later I would discover that Stern’s memoir, his novel, and assorted essays on music, medicine, and religion had made him a quasi-celebrity. Back in 1939, his young family settled in a jerry-built row house near the mental hospital where he worked on Montreal’s outskirts. A decade later, he would become one of Canada’s founding fathers of psychiatry. He would write best-sellers like The Pillar of Fire, reprinted 17 times in paperback and translated into Spanish, French, Italian, Dutch, and German. His 1961 study on psychology and religion, The Third Revolution, would spark correspondence with Carl Jung. The Flight From Woman (1965), a philosophical treatise on modern society’s polarization of the sexes and its de-feminization, would make him a common name in women’s magazines. He corresponded with leading rabbis, poets, and writers—Robert Lowell, Ivan Illich, C.S. Lewis, Thomas Merton—and other religious luminaries of his day. Along with Jean Piaget and Maria Montessori, he would join UNESCO’s Committee of Experts on German Questions. Graham Greene was his houseguest. American Catholic activist Dorothy Day was a close friend. He would be profiled in Time and write for the New York Times.

The Munich museum expressed gratitude for my donation, although they’d never heard of him.

How did Karl Stern become so forgettable? Little has been written about him since the decades following his death in 1975. The list of heavyweight European intellectuals who fled to North America—the Arendts and Adornos, Horkheimers and Fromms—is so long. Is it any wonder that so many others, especially north of the border, have fallen through the cracks?

On the plane to Munich, I read The Pillar of Fire from beginning to end. It is breathtaking. As a historical document, it is nothing less than essential, a pre- and post-1933 doctor’s version of Joseph Roth’s What I Saw, a Who’s Who of Jewish-German life. It possesses that tinge of self-effacement that readers may find endearing and that builds confidence in the narrator’s authority. But by the time we landed and I had closed his book, I understood why Stern may have been easier to forget.

Born in 1906 to an assimilated merchant family in Cham, about 90 miles from the Bavarian capital, Stern is one of those rare figures who, by luck or preternatural talent—in his case both—survived some of the most dangerous episodes of European history. Between the wars, he joined the Jung-Jüdischer Wanderbund(Young Jewish Wanderers) that held meetings on Thierschstrasse, next to Hitler’s original headquarters. Like many young idealists, he dabbled with Marxism and then became a Zionist and part of the habonim. He attended the Orthodox Canal Synagogue on Herzog Rudolf street, where he met Martin Buber. He underwent analysis and trained to be a doctor with some of the 20th century’s most brilliant minds.

He exchanged letters with Thomas Mann. Struck up a deep friendship with Reha Freier, who founded the Youth Aliyah and saved thousands of Jewish children from deportation (“She was beautiful, of a simple Biblical beauty, someone right out of the Old Testament.”). A talented pianist, Stern played Bach’s chamber music in the salons of the well-to-do.

When Hitler came to power, another lucky break. His work at the German Research Institute for Psychiatry was paid for by a Rockefeller grant. He became the only Jewish physician in a non-Jewish institution in Nazi Germany allowed to work under the Aryan laws (until his sympathetic supervisor, Dr. Walther Spielmeyer, died in 1935). Soon he escaped to London, where he conducted important neurological research on dementia. Meanwhile, his brother Ludwig, a Zionist leader, was miraculously released from Buchenwald. His parents were also saved, but he lost extended family and many friends to the death camps.

Stern’s book is a backstage pass into the perverse inner machinations of life in Nazi Germany from which most Jews had already been banished to the harrowing margins. But this is a subfraction of his story’s central theme. The Pillar of Fire is also an account of Stern’s conversion from Judaism to Catholicism. From Munich’s Canal Synagogue on the eve of European Jewry’s destruction Stern is received, in 1943, on the Vigil of Saint Thomas of the Apostle, by Father Ethelbert Sambrooke into the Dorchester Street church of Montreal’s Franciscan Fathers.

His early spiritual awakening is guided by the unlikely figures of pious Bavarian housekeepers, many of whom, he explains, had an instinctual disdain for Hitler. “What do they want to do against the Jews?” asks Babette Klebl, the Catholic maid of family friends in Munich, about the Nazis. “It will end badly with these fellows because our Lord Himself was a Jew.”

In his memoir, Stern speaks with unbridled admiration about women like Klebl, and Kati Huber, the maid of his future wife, who are a balm for his restless intellect and exude “the odor of hard work, the righteousness of the Psalms and the peace of the Gospel.” They display a natural charity and “treasure of anonymous sanctity.” Their simple but mysterious faith is juxtaposed with the somewhat dreary Jewish reality of Stern’s childhood, the mediocrity of his first religious teachers, and the damp, smelly prayer-hall housed within a brewery in his hometown. Even his aunt Clara, of whom he usually writes fondly, can only express sarcasm about his bar mitzvah celebration, which ends with a cousin playing Wagner’s “Magic Fire” from The Valkyrie on the piano.

After many years of wrestling with spiritual questions like Jacob and the angel, Stern finally exchanges his tefillin for the rosary, Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. “We all go through … mental contortions before we have torn up our earthly roots,” Stern reflects on accepting Jesus Christ as saviour, “and let ourselves fall into space and into the great embrace.”

Stern’s fall into the great embrace catapulted his name beyond Montreal’s hospital wards and the leafy campus of McGill University’s medical school, into a postwar universe of broken souls yearning for spiritual comfort. Over 60 years later, Catholic readers still draw on his memoir for nourishing their faith. Dr. Bernard Nathanson, a Jewish convert from New York who co-founded the National Association for the Repeal of the Abortion Laws, credited The Pillar of Fire as an inspiration behind his own turn toward Catholicism and the pro-life camp. “There was something indefinably serene about him,” he writes of Stern, who was also his professor at medical school. Stern’s memoir, Nathanson wrote, was “perhaps the most eloquent and persuasive document on the experience of religious conversion written in the modern age.”

Despite The Pillar of Fire’s reputation as a wellspring of faith and conviction for Catholic readers, there has been little biographical probing about his life beyond it and even less interest in some of his other achievements. He is frequently positioned alongside Edith Stein, the philosopher and nun, and Israel Zolli, the chief rabbi of Rome. Stern, however, is more than a Catholic curiosity for unbelievers or an historical novelty. The explosive popularity of his book speaks to an important moment when Jewish conversion stories were highly esteemed by non-Jews, while being a heavy burden for Jews.

In the 1950s, Jews may have wished to forget Stern entirely. His public confession during the “post-gas chamber period of history,” as he called it, incited anger and more anguish. As a psychiatrist who had undergone psychoanalysis, he wove clever Freudian allusions into the story of his spiritual life, adding a premeditated dash of self-deprecation. “To write the story of a conversion is a foolish undertaking, for the convert, the ‘turned-around,’ is a fool,” he says. There are, as some reviewers remarked, very few notes of foolishness. There are mellifluously constructed passages that stick to the well-trodden path of other conversion narratives. Like many converts before him, Stern saw Christianity as Judaism’s logical fulfillment, not its rejection or its end. In recalling his first Holy Communion, he writes that his spiritual identity had converged both with Christians but also with Jews. After many years of indecision, baptism made him feel closer to Jewishness.

“And it was if others were there,” he writes, referring to his former co-religionists, “my parents … the Kohen family, the Jews from the Canal Synagogue. … And there was no doubt about it—towards Him we had been running, or from Him we had been running away, but all the time He had been in the center of things.” Psychoanalyst Erich Fromm called Stern “an insecure and confused man,” in his review for the New York Herald Tribune. In Commentary, Moshe Decter offered a respectful critique, hinting that Stern would be wrong to think his Jewish brethren would be happy accompanying him to the baptismal font. He argues that Stern had fallen into the trap of a mistaken Christian apologetics, and leaves it at that.

But some of Stern’s lines are worth quoting at length, if only to imagine the reaction Jewish readers may have had, while Adolf Eichmann was still at large and Simon Weisenthal had started hunting war criminals:

Now I was shaken … by the following fundamental and indisputable facts. Firstly, there were two parties who unanimously and in perfect agreement maintained the racial wall around the God of Sinai—these were the Nazis and the Jews. Let there be no mistake. Jewish religion up to this day is based on the axiom that Revelation is a national affair and that the Messiah to the Nations has not been here yet. Do not be misled by the fact that Jews in their personal ethics are anything but exclusive and racist. Do not be misled by certain noble Talmudic principles such as “The just of all nations have a share in the world to come.” This latter idea has no bearing on the question discussed here; it deals with what to Jewish antiquity was the “invisible church.” Do not be misled by the fine cosmopolitan sentiments and actions of reformed Judaism which are often prompted by noble hearts but at the same time by much vague thinking and by a lukewarm dilution of the most profound and world-shaking elements of the Judaic treasure. No, there is no getting away from it. Revelation was still contained within the precious vessel of the Nation; I only had to look at our liturgy to see that this was so. Jewish religion was racial exclusiveness. Mind you, it was racial exclusiveness in its noblest, most elevated form—in its metaphysical form, so to speak. It was a racism exactly opposed to that of the Nazis, but it was racism just the same.

Upon hearing Hitler’s speeches on German racial superiority, Prelate John Maria Oesterreicher, an Austrian Jew who became a Catholic priest in 1927, apparently said, “Thank God I am a Jew and I can’t be duped by this.” From reading The Pillar of Fire, it’s possible that Stern could have heard these very same speeches and, with his knowledge of psychoanalysis, understood that Nazi propaganda belied Hitler’s inferiority complex and even homoerotic impulses. Where Stern had difficulty, perhaps, was in parsing the various impulses behind his own thoughts on Jewish racial exclusivity. Did he project his own neuroses and guilt about converting to Catholicism, which at that time condoned anti-Semitic teachings, onto the Jewish fold he was about to abandon?

“The book was persuasively written,” recalls Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi in his book My Life in Jewish Renewal, about Stern’s memoir. “[A]nd at the time I felt half-torn between running to the nearest Roman Catholic priest and immediately burning it.”

Stern and Schachter-Shalomi eventually became friends. They’d meet in Stern’s office at Saint Mary’s, where they’d discuss Freud’s five stages of psychosexual development and its application to religious experience. But Schachter-Shalomi’s initial outrage put him in good company. In 1952, Rabbi Bernard Heller, a professor at New York’s Hebrew Union College, published Epistle to an Apostate,an entire book dedicated to refuting Stern’s Pillar of Fire. Described as a “strenuous little book” by Arthur Powell Davies in the New York Times, the tone of Heller’s writing does, on occasion, escalate to a hysterical pitch: He discusses the deceptive power of Pillar and its “danger of leading astray the uncritical and unenlightened.” (One chapter, for example, is wryly titled Pillar of Fire or Smouldering Stump?)

In his defense, Heller took less than a year to formulate his refutation, which he never intended as a display of literary acumen in the way that Stern, with his quotations from Tolstoy and Goethe, did. The “strenuous” tone ostensibly belied the anxiety most Jews had in a post-Auschwitz world about public perceptions of their religious and cultural life. Heller was no stranger to the works of earlier converts and apostates, but his sense of urgency and “unshirkable duty” to repudiate Stern’s “missionary tract” is palpable. “No Jewish convert to Christianity has displayed the literary and dialectic skill that Karl Stern did,” he writes, fearful of his book becoming a vector for more leaps of faith, “nor has any convert had a more engrossing and political setting for his story.”

Heller corrects Stern’s erroneous explanations of Jewish laws and symbols, as well as his ignorance of Talmudic sages. Among other errors, Stern mistakes Simchas Torah as “the feast of law giving” instead of its marking the completion of the reading of the Pentateuch. These glitches are not insignificant for a writer whose popular book would, by default, extend knowledge of Judaism to non-Jews.

But one thing bothers Heller most of all. Pillar of Fire’s final section, called “Letter to My Brother” is a figurative epistle to a universal Jewish fraternity. But it is addressed to Stern’s younger brother Ludwig. In contrast to Karl’s, Ludwig’s life would end up on the opposite pole. He would move to a kibbutz and change his name to Shimon Shavit. In Letter, Stern argues that the only alternative to the suffering both brothers have witnessed, and the only way to find meaning from the horrendous deaths of their relatives in the camps, is through belief in Jesus Christ. Stern presents the paltry 20th-century alternatives: Zionism, Marxism, nihilism, and scientism (as a number of reviewers noted at the time, he doesn’t include Judaism as a possible spiritual path).

“One cannot abstain from wondering why your brother apparently did not deign to reply to your letter … and if he did answer you why you refrain from publishing it,” Heller writes, confronting Stern in his book.

Daniel Burston, a professor of psychology at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, has asked the same question. “I wanted to know, frankly, how Stern got along with his brother,” he explains to me on the telephone from his office. But unlike Heller, Burston has found the answer through Karl’s and Ludwig’s letters, which he’s used in his forthcoming biography of Stern with McGill-Queen’s University Press.

The reply Burston found is a happy one, and perhaps surprising. “[The brothers’] relationship flourished, even after The Pillar of Fire was published,” he tells me. “They visited one another’s homes and families and exchanged letters regularly. Stern was very proud of Ludwig/Shimon, despite his pointed rejection of Zionism—and nationalism in all its forms.” Burston adds that Stern had a remarkably “soft landing” with his family compared to what he got from the Jewish community in Montreal, which from all accounts, rejected him.

Burston was born in Israel and brought up in a labour Zionist household, and he has taught psychology at Duquesne, a Catholic university, since 1992. A scholar of the history of medicine, psychology, and psychoanalysis, he’s published books about Erich Fromm and R.D. Laing. His discovery of Stern came early, at age 18, when a Catholic friend recommended The Flight From Woman. Years later, while researching his book on psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, Burston stumbled upon Stern’s work again at the Austin Riggs Center, in Stockbridge, Mass. This time, he “devoured” The Pillar of Fire and vowed to write a book about Stern as well as put him back on the map.

Like me, Burston wants to understand why Stern has been forgotten. He’s found a home for Stern’s papers at the Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center at Duquesne, which opens officially this fall. He’s used Stern’s Third Revolution for teaching courses, but his upcoming book will no doubt revitalize scholarly interest about the psycho-social aspects of conversion, as well as Stern’s other writings in medicine and psychology.

He is also examining Stern’s attempt to “baptize” Freud and to defend psychoanalysis’ compatibility with faith. To make it kosher, in other words, for Catholics; but by extension to show that there is nothing anti-religious in psychoanalysis that the faithful of all stripes should feel compelled to reject. While Stern makes an excellent argument for unconventional interpretations of Freud, Burston suggests that this position would have banished him, as a psychiatrist, to a professional no-man’s land. Stern’s belief that psychoanalytic concepts such as the libido, transference, and sublimation were compatible with Judeo-Christian teachings would have ruffled the feathers of Freudian purists, particularly as his book on the subject received the imprimatur of the archibishop of Ottawa. “As a matter of fact,” Stern wrote in The Third Revolution, “according to psychoanalytical teaching you have to know your own depth … if somebody’s moral philosophy is based on the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the acquaintance with psychoanalysis often deepens his sense of natural charity.”

Burston also looks at the psychodynamic psychiatry practiced by Stern as it fell out of favour during an era when medicine was rapidly moving forward with great technical achievements. Stern wrote frequently on modern medicine’s dehumanization of patients, a subject that may have been contre courant during an era of electroshock therapy and new trends in psychopharmacology. The very forces that made his work unpopular then may create interest today. Burston is confident that the critical climate of Big Pharma monopolies and the dashed hopes of wonder drugs like Prozac and Zoloft may give Stern’s writing a renewed appeal.

And, while the “Jewish racism” discussed in Pillar of Fire is deeply troubling, we can still learn from it. “What we don’t need now is another edition of Bernard Heller,” Burston writes to me in an email. “I’ve crafted my book in such a way—I hope—that Catholic audiences will recognize how problematic [Stern’s] rhetoric is now in a post-Vatican II environment, and reflect seriously about some lingering sources of mistrust that prevent further dialogue.” He adds, “The Pillar of Fire is an important book because it illustrates, for Catholics, how not to address and engage with Jewish interlocutors during the course of interreligious dialogue in the wake of Vatican II.”

Burston sent me a copy of his manuscript. Stern’s life in Canada was filled with moments of spiritual peace interspersed with tremendous pain. I’ve read hints of this elsewhere, in the letters of Dorothy Day. “He is a daily communicant, and a deeply suffering man,” she writes of Stern to Thomas Merton, the mystic, author, and Trappist monk. “I sometimes think that without his writing and his music he would collapse.” Burston’s biography also addresses the anguish that Stern’s family endured later in the 1960s. His son Antony, who also became a psychiatrist, committed suicide at the age of 30, leaving his wife and four young children behind. Stern’s wife Liselotte, one of the world’s few women master bookbinders, allegedy suffered from what would be diagnosed today as bipolar disorder.

The biography is the first to dedicate a serious discussion to a thinly veiled fictional account of Stern’s domestic dramas in a highly acclaimed 1975 book-length poem, In & Out,by Canadian-born writer, Daryl Hine. Widely respected by critics like Harold Bloom and Northrop Frye, it is a story of Hine, the former editor of the prestigious Poetry magazine in Chicago, dabbling with Catholicism and his sexuality as a gay man as a student at McGill. Aside from Hine’s close friendship and alleged romantic affair with Stern’s son, Antony, the poem presents Karl (in Hine’s book he is given the pseudonymImmanuel Star, author of The Pillar of Salt) as an emotionally distant, tyrannical father. “[A] noted psychiatrist, also / a Jew, had converted, a few / years ago, to the Catholic Church / and had taken his wife and his children / like luggage or hostages with him.” Stern tries, according to Hine, to coerce him and his son into a cure for their homosexuality. “Hidebound / an orthodox Freudian, orthodox / Jew in his youth / ultra-orthodox / Catholic now,” Hine writes sardonically, “living proof of the great Judeo-Christian tradition.”

Burston’s research suggests that Hine’s depiction is factually sketchy. (I contacted Hine’s literary executor, Dr. Evan Jones, to back this up. He never responded.) He details other inconsistencies, suggesting that Hine used a hefty amount of poetic license with his description of the family. The nasty portrait of Stern in particular may in fact be a caricature or distorted symbol of the poet’s own bitter disillusionment with Catholicism and faith in general.

The timing of Stern’s conversion was much later than that of his wife or two eldest children, putting his religious “tyranny” in question. But the importance of Hine’s poem, published the year of Stern’s death, may be less about the tragic truths or untruths it holds. Its publication would have shocked into silence anyone in their shared intellectual circles. At the very least, it would have elided opportunities for many of Stern’s admirers, or even his respectful critics, who would fear dispatching his family demons farther afield.

As a foreigner, Stern would not have been shielded from Montreal’s anti-Semitic climate in the 1940s. McGill had a quota for Jewish students and faculty, by some accounts well past World War II. Alfred Bader, later a Harvard-educated chemist and philanthropist, arrived in Canada just after Stern, and he was refused entry as an undergraduate. Stern eventually taught there, but his academic appointment was possibly stalled because of his being Jewish.

Anti-Semitism came from all sides, and this is something that Stern felt, regardless of his formal severance from Jewish life. In 1939, he may have even encountered the Fascist rallies or flyers written by men like Adrien Arcand, who called himself Le fürhrer canadien, and held meetings in Montreal’s Catholic churches. “In Germany we had been subject to the cruel precision of a huge anonymous machine; here for the first time we experienced anti-Semitism from person to person,” Stern writes. This is also stressed in the popular literature of the period. “After all,” says Erica Drake, the Protestant protagonist in Gwetholyn Graham’s best-selling 1944 Earth and High Heaven,a novel that takes place in Montreal, “we Canadians don’t really disagree fundamentally with the Nazis about the Jews—we just think they go a bit too far.”

Burston attempts to find evidence of Stern’s meaningful contact with the Jewish community. By most accounts—or lack of them—he was persona non grata. It is unlikely that he would have discussed his religious quandaries with the small group of Jewish interns at McGill. Or over a nosh with the Yiddish-speaking tailors and cobblers at Wilensky’s Lunch. And yet, as Burston explains, Stern became an outspoken critic of anti-Semitism within the church and in political circles. “The drama of Golgotha is the drama of all mankind,” he writes in his essay “Some Religious Aspects of Anti-Semitism.” “The fact that the mother of Jesus was a Jewess, that all his early friends and followers were Jews, that he himself in the flesh was a Jew, is kept from the [Christian] child’s conscience.”

It may be impossible to find traces of Stern’s spiritual life, or his conflicts, in the scientific research he conducted at McGill. I did, however, find notable a psychiatry paper, “Grief Reactions Later in Life,” published in the same year as The Pillar of Fire. Stern and his colleagues argue that elderly patients do not exhibit overt grief or guilt when a loved one dies. Instead, they frequently suffer from somatic illnesses and a “tendency to extreme exaggeration of the common idealization of the deceased with a blotting out of all ‘dark’ features.” Guilt, they explain, using Freudian concepts, is “channeled” into somatic illness. The elderly also “preserve an image of the deceased consisting only in light and without shadow.”

I asked Burston if this paper could serve as a metaphor for any future guilt Stern may have had, or if he had felt no compunction, about his rejection of Judaism. Stern became very ill, suffering from a heart attack in his early fifties and then a debilitating stroke. At the same time, he became more engaged with public dialogue on anti-Semitism. Was his illness part of the grief? Did he have an exaggerated guilt reaction later in life?

“Not later in life,” Burston wrote me back. “Stern was really ripe for conversion in 1933, but delayed being baptized till 1943 as he tried to overcome his ‘traitor complex.’ These are his words, not mine. He was only partially successful because those feelings returned to haunt him, especially after his son’s suicide.”

There are traces of this “traitor complex” in his memoir. At one point, he proclaims his determination to remain Jewish out of duty; and yet, like writers such as Franz Werfel and Scholem Asch, whose work expresses admiration for Christianity and the figure of Jesus, Stern still felt it that may be possible, he writes, to “guard the secret of Jesus” privately without changing his outward life as a Jew. “It was impossible that, at this moment when our people were undergoing its agony,” he explains, “even Christ himself would demand one of us to become a deserter.”Upon meeting the Catholic intellectual Jacques Maritain in the salon of a French-Canadian family, Stern told him “that I often believed that my conversion was nothing but a mirage produced by an unconscious desire to escape the destiny of a Jew.”

In the middle of my research, I put aside all my books and photocopies about Stern’s life and work. I decide to fly to Pittsburgh to visit Burston and the archives at Duquesne. I wanted to see Stern’s letters, written in the cursive script that I first discovered years ago, in the book I gave away. I even tried brushing up on my German, which is limited to ordering coffee and buying train tickets. But I developed a mysterious red swelling on my left arm. It got bigger and more aggressive-looking. My doctor suspected a blood clot and sent me to the Jewish General Hospital affiliated with McGill. Stern, it turns out, taught at the psychiatry department here in its early days, along with virtually every other teaching hospital in Montreal, and in Ottawa.

I spent days being carted back and forth from waiting room to CT scans and ultrasounds in the bowels of the building where Stern’s patients probably sat waiting for tests. During one appointment, I shattered the screen of my smartphone. The only thing I could access were sound recordings I’d made of Stern’s interviews from TV programs on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and its French equivalent, Radio-Canada.

I listened to them on my shattered phone, over and over. Stern is lively in his 1968 French interview about psychiatry. He gives detailed answers peppered with jokes, making the Québécois audience laugh. He explains why Joan of Arc would be classified as psychotic in the manuals of modern psychology. He speaks an accented French, using occasional turns of phrase like the ones that would be learned by European students on their grand tour.

The mood changes when his interviewer, a popular journalist named Fernand Séguin, asks Stern about life in Nazi Germany. “You suffered because you are of Jewish origin?” “Oui,” Stern replies, curtly. “So you left Germany?” Séguin persists. Stern’s voice wavers, exhausted. He lets out a long breath. “Oui, à temps.” (Yes, just in time). Séguin asks Stern to discuss anti-Semitism, and what he has experienced as a Jew in Canada. “French and English Canadians,”Seguin says, “don’t make soap out of Jews, we don’t have gas chambers, but …”

It had been over two decades since Stern’s conversion and his breaking of ties with the Jewish community. For Catholics and the wider public, however, he remained a bridge and spokesman to understanding the Jewish experience of the world.

In his earlier appearance in 1965 on the popular Canadian documentary show This Hour Has Seven Days, Stern is asked to present a psychiatrist’s understanding of the pathologies behind group hatred and anti-Semitism, including the neuroses and projection mechanisms at play in all acts of prejudice. The show profiles two of the country’s worst offenders: David Stanley, a clean-cut youth out of high school who distributes anti-Semitic pamphlets on the streets of Toronto; and John Ross Taylor, a “hate peddler” who wishes to ship world Jewry to Madagascar. At the program’s end, Stern is asked to give some final words to “cleanse the air.”

“You can engineer and you can manipulate hate,” Stern says in a staccato, professorial voice. “You cannot engineer and manipulate love. And yet love in the long run will always be victorious.”

Long after Stern’s death, the Franciscan church on Dorchester Street, where he took his first communion, was abandoned for lack of funds. Later, it burned to the ground. Stern missed the final days of Quebec’s révolution tranquille, a turbulent period of secularization that ultimately destroyed the Catholic Church’s hegemony over government, education, and culture. For years, Quebec has been rife with church sex abuse scandals. Some of the most horrific crimes against children and orphans occurred in Catholic schools just miles from Stern’s office at Saint Mary’s, at the time when the galley proofs for The Pillar of Fire sat on a proofreader’s desk at Harcourt Brace and Company, in New York.

But Love will always be victorious. Stern tried to find spiritual proof for this all his life, and it is something that he truly believed. That’s an achievement in its own right, given the horrors of the era in which he lived. He may have felt about himself as he did about Montreal when peering down at the parcellated areas of the city, filled with distrust between Catholics and Jews, English and French. Perhaps some of his own suffering originated in the parcellated fragments from within, the Jewish roots that he severed but that he also tried to protect. Writing about these paradoxical feelings hurt the people with whom he had shared a faith and tradition and with whom he will always be identified. “All stories of conversion appear to have something subjective-arbitrary, some tragic secret,” he writes in The Pillar of Fire. He knew this more than anyone else.

There is no denying that Stern’s fall into the great embrace was sincere. But accepting his sincerity, and the importance of his legacy, will always mean questioning the intellectual and psychological leaps he took to break his fall.

Deborah Ostrovsky is a Montreal freelance writer whose articles and reviews have appeared in numerous Canadian magazines, as well as the anthology Cabin Fever: The Best New Canadian Non-Fiction.