The Forgotten Founder of ‘Partisan Review’ Wrote Porn and Thrillers

What happened when Kenneth Fearing’s Communist sympathies came up against his ideas about art?

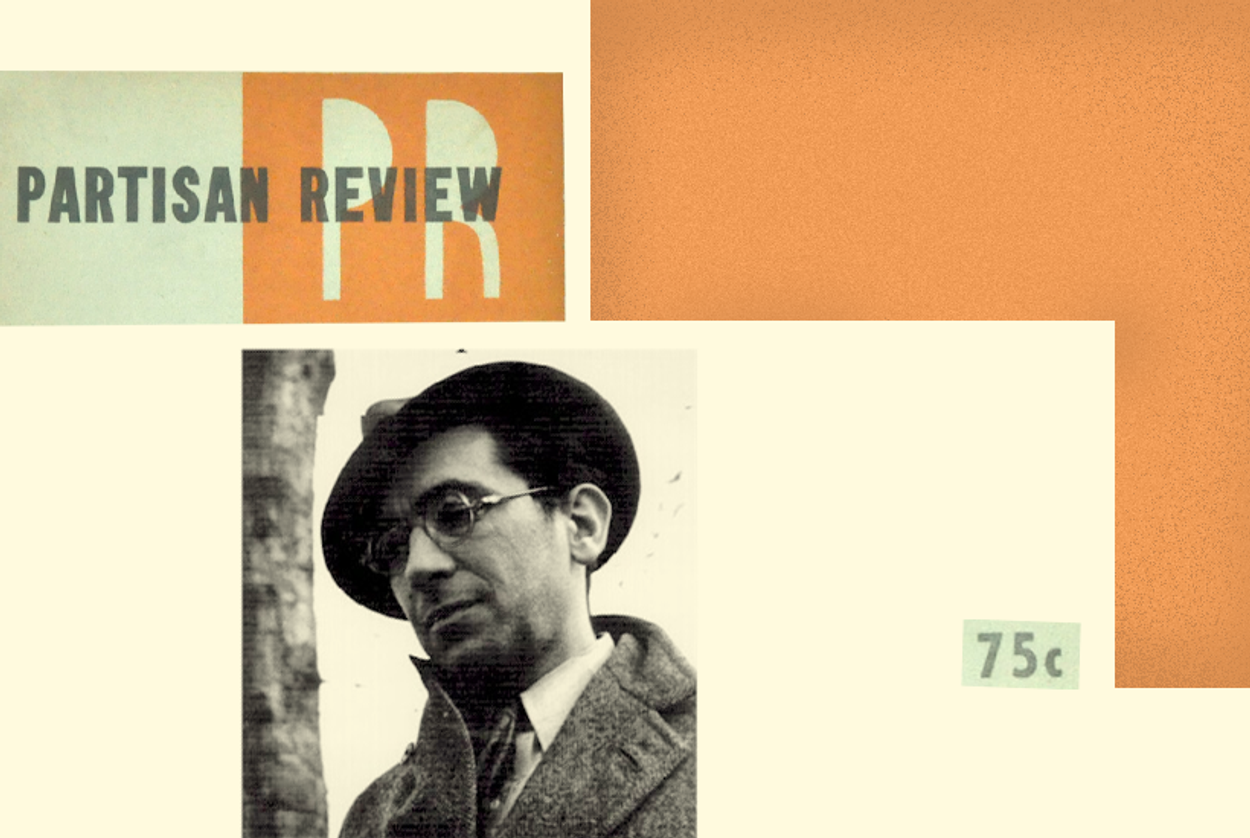

Founded 80 years ago, Partisan Review is remembered for the editorial vision of two of its founders, William Phillips and Philip Rahv, who within two years transformed the magazine from a pro-Stalinist periodical advocating “art as a political weapon” to an anti-Stalinist one promoting “art for art’s sake.” Phillips and Rahv were castigated for the switch by the American Communist Party. But a third founder of the magazine, poet and thriller-writer Kenneth Fearing, has been largely forgotten, in part because he was suspected of being a Communist, and in part because he wrote thrillers.

When Fearing, who died in 1961 and would have turned 102 this week, was asked the $64,000 question when he appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950—“Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”—he answered, “Not yet.” While this was possibly a throw-away line or an attempt at humor, Fearing was more right than he knew. He never quite made the leap into social realism. Instead, when writing hardboiled mysteries, he served the story rather than the Party’s aesthetic dogmas.

Not even the advent of McCarthyism moved Fearing closer to the Party. With the Party working overdrive in proclaiming McCarthy’s America fascist while lauding the Soviet Union, Fearing instead attacked both. He predicted that the congressional investigations would follow the same trajectory as Stalin, resulting in “mass executions.” When Robert Cantwell, an informer during the blacklist, rose to give the eulogy at his funeral, Lillian Hellman staged a walkout.

Like many leftists, Fearing, born in 1902, came from distinguished surroundings. His father was a successful Chicago attorney whose ancestor was a Coolidge. His mother, second-generation Jewish, had a cousin who helped found the Institute for Advanced Learning at Princeton. Despite his plush upbringing, Fearing favored a bohemian life style, which eventually forced his resignation as student editor of the University of Wisconsin’s literary magazine for accepting stories dealing with sex and violence. Moving to New York and settling in Greenwich Village, Fearing wrote sex stories for the pulps in order to subsidize his more “serious” work. But although Fearing’s more “serious” stories and poems were accepted by The New Masses, privately the editors dismissed his work as “art for art’s sake.”

He had his own personal opinions about the Party as well. While the CPUSA was praising his second collection of verse, Poems (1935), Fearing mocked such labeling since his poems merely described the revolutionary process rather than endorsing it. Although the praise continued for the rest of his life (leading many, including the FBI, to conclude he was a Communist Party member), Fearing’s relationship with the Party was problematic: A pacifist horrified by World War I, he attacked the Party’s mid-1930s pro-collective security stance dictated by Moscow. A Jew and anti-fascist (he grew up hearing the “fashionable anti-Semitism” of his father’s upper-class friends), he was equally at odds with the Party’s support of the military partnership between Hitler and Stalin in 1939.

Switching genres did not bring him more in line with the Party. The plot of his first thriller, Dagger of the Mind (1941), involved a New York State police officer capturing a murderer who then dies in the electric chair. If Fearing had been writing in the Marxist vein, then he would have portrayed the cop as a corrupt thug in the pay of the rich. But his “art for art’s sake” technique of rendering each character in first person, and thus having to treat each one as complex, frustrated such simplistic propaganda.

By the time of his most famous work, The Big Clock (1946), the Left had adopted noir as the best means to slip anticapitalist propaganda, under the guise of a fast-paced thriller, past conservative studio heads. Tinseltown Communists Edward Dymtrk and Adrian Scott used Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely (ironically Chandler was conservative) to portray a corrupt society peopled by bought-off cops and fascist millionaires.

On the surface, The Big Clock would seem to be in this vein. Earl Janoth, a business executive modeled on Henry Luce, murders his mistress and then attempts to pin the blame on her mysterious lover who, unbeknownst to him, is George Sandos, the investigative reporter tasked with uncovering the identity of the killer. In a play on media and congressional investigations of citizens’ leftist pasts, Fearing has George provide a clue to his affair when he and the mistress purchase a painting of a WPA artist; hence, as with the sympathies of those investigated by Congress, George’s affection for an aspect of New Dealism could land him in jail.

But upon closer examination, the story is hardly Marxist. The typical proletarian novel had a protagonist, either apolitical or vaguely liberal, who watches a strike from the sidelines. The story usually ends with the murder of a union organizer friend by the bosses. The murder radicalizes the protagonist, who in Tom Joad fashion, pledges to carry on the work of the martyr.

But Fearing doesn’t honor the conventions of the genre. Although the villain is a capitalist, he doesn’t murder his mistress out of greed, but because she wounds his masculine pride (she accuses him of homosexuality). George’s consciousness was hardly raised by the murder. He isn’t after the villain because he is an exploiter but merely to save his own neck. George’s fascination with the WPA artist is not followed up on (a proletariat novelist would have used the painting of money changing hands as a means to “awaken” George). A useful plot device might have had George uncover some business illegality in Janoth’s closet—thus providing George with potential blackmail material should he be exposed. But this line of inquiry is not pursued, possibly because such an undertaking would have slowed down the breakneck pace, the lifeblood of the thriller genre, and Fearing clearly serves the story rather than adapting it to Marxist dogma.

The abrupt conclusion of the novel, with the last line reporting Janoth’s suicide, has been cited as proof that Fearing did not know how to end novels. But the reality might be that he wrote himself into a corner. A Marxist ending, such as George at the grave of the mistress pledging to join a progressive magazine, would not have played fair with the reader, given that George neither evinced any sympathy for her death nor appeared to care about the plight of the workers. Fearing did, but he cared about the integrity of stories more.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ron Capshaw is a writer living in Midlothian, Va.

Ron Capshaw is a writer living in Midlothian, Va.