King Without a Beard: The Rise and Fall and Rise of a Former Reggae Star

As Matisyahu tours on ‘Spark Seeker,’ will his pop fans snuff out the spiritual fire that lifted him to the top of the charts?

The Tablet Longform newsletter highlights the best longform pieces from Tablet magazine. Sign up here to receive bulletins every Thursday afternoon about fiction, features, profiles, and more.

Around Matisyahu’s tour bus, milling outside, a few Orthodox Jews under black hats huddled for warmth in the New Jersey cold, making small talk. It was President’s Day, in Morristown, a few seasons ago, which is how a lot of people remember Matisyahu. They probably remember that Matthew Paul Miller made his name as the Lubavitch Luciano, singing a compelling admixture of Orthodox Judaism and reggae. They remember how he took two of the most staid ideas in the universe—at least in terms of mid-2000s pop culture—and twisted them into something vital, a giant beat-boxing beard at the head of a farbrengen, or joyous gathering, with a voice that commanded attention. They remember “King Without a Crown,” how it became a hit (No. 28 on Billboard’s Hot 100), got excessive radio play, popped (annoyingly) into their heads without warning during otherwise leisurely strolls—and how the moment passed. That was around 2006.

Now it was February 2013, and if anything since then had flitted through the attention-addled megabrain of pop fandom, it was probably that Matisyahu is no longer Orthodox. “No more Chassidic reggae superstar,” he Tweeted in 2011, though he kept the single moniker. It’s not like he had been silent for the past seven years, not at all: a few gold albums and another insidiously catchy hit, “One Day,” sure, but compared to Beardgate, which was the Miley Cyrus Twerking of the Orthodox world? Bubkis. So, as I walked past the young Orthodox men, on my way to interview the former star and current musician about his tour promoting two releases—last year’s Spark Seeker and an EP of acoustic versions of songs off that album—I was as surprised to see so many black hatters as the black hatters were to see me. (I later found out that they were mostly fans and crew of the night’s opening act, Levi Robin.)

Inside the bus, seated at some Formica tables, Matisyahu seemed more interested in his sandwich than whatever we might have to talk about, but it wasn’t long until a match came: One of the Orthodox millers-about and I had gone to the same high school, played for the same basketball coach, whom we both knew as Coach Chad. Matisyahu seemed amused, his manager a bit frustrated—the interview was starting to derail. Talking about Coach Chad, the miller-about, named Eli, brought up some old racist bullshit I hadn’t heard in years. Behind his back, everyone had called Coach Chad a “white black man,” because he didn’t talk or dress like the only other black people students at Shalhevet High School were remotely familiar with: rappers. And now Eli was doing it again, laughing about Chad’s gigantic size and how he “acted white.” No one in the tour bus seemed to flinch at it, although Matis, as he’s often known, came closest, giving Eli a look and asking for qualification of the statement. Eli demurred; the manager shoved him out.

Ostensibly, I was there because Matisyahu was then on tour, as he is now, scheduled to play in New York’s Central Park over the High Holidays. He’s on a small-venue U.S. run that extends to three shows in Israel (one on Masada, historical birthplace for Jewish rebellion) and finishes with an acoustic set at the end of September in Tel Aviv’s Zappa Club. Spark Seeker hadsat atop Billboard’s Reggae chart for 29 weeks, until Spark Seeker: Acoustic Session, his newest album,replaced it in February—then the two sat together atop the chart through March, lording over Sean Paul and Jimmy Cliff. The original Spark Seeker, though it came out in July 2012, is now up to 57 weeks in the top 10 and currently ranks as No. 6. Acoustic Session, which came out January of this year, is a live recording that finds Matisyahu where he’s most comfortable—letting his tremendous voice fly, with some preaching and some improvisation. Even eye-roll-inducing lines like, “Let go/ Of what you know/ Return to the land of the rainbow” are sung well enough to be taken at close to face value.

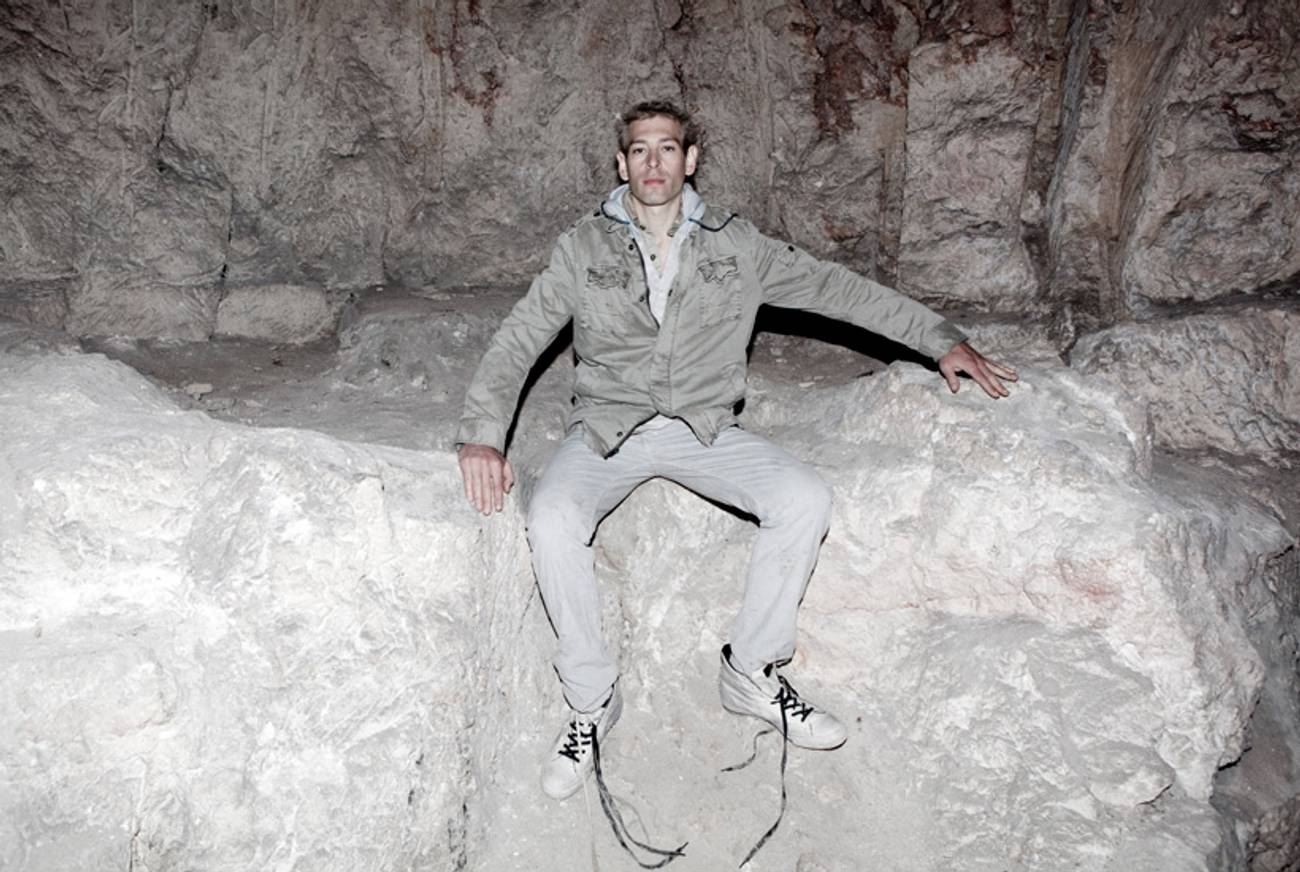

In reality it seemed, though, I was there to watch Matisyahu as he—tall, tired-looking, face full of stubble—ate his sandwich. His answers were mostly mumbled, short, and given looking out the window. He fumbled with a cigarette some of the time. He wasn’t being rude, I thought, he’s just bored. His electronic influences? “No specific bands, just sounds I hear these days,” he said. The vibe he gave seemed quite right—a spiritually inclined, vegan, hippie dad (three kids) who was getting ready to go to work. As soon as I turned off the digital recorder, Matisyahu perked up. When his manager reminded him that another music-press interview was coming up, Matisyahu got bummed out again.

In all fairness, Matisyahu is beyond this—the whole getting-badgered-by-press-in-the-tour-bus thing. He’s a master of social media, and that’s where the people are. The physical realm of the in-person interview need not concern him anymore. He has reached a spiritual plane where 1,698,908 Twitter followers, 1,042,948 Facebook fans, and 30,674 Instagramers follow his every word, like, and #nofilter. They’re not Lady Gaga numbers, but life as a B-lister needn’t be so bad. He’s as open as can be around his fans, sharing a surprising number of triumphant shirtless pics, his musings on Rosh Hashanah, and his queries to Christians about why they like Christmas songs. He shows off his son and regularly chooses an Instagrammer of the Day. Even that vegan sandwich he was chowing down on has a powerful social media presence, chronicled on the What Does Matisyahu Eat? tumblr, managed by his personal chef. And it’s easy to see why Matisyahu loves the direct interaction. Before his first big hit, cultural gatekeepers denied him for years. Now, even after his fall from pop-phenom heights, he’s still standing—thriving, actually—because a group of people, mainly Jews but also not, kept him afloat. Maybe he can’t sell out Madison Square Garden anymore, like he did Jan. 14, 2006, but he can sure as hell sell out Skokie, get European tours and Jewish Community nights at ballparks, and rock Masada.

***

It’s an addictive feeling, being part of the Matisyahu fan base, as I have been ever since my days at Shalhevet High. All the friends who I’ve told about this article have looked in disbelief for a second—laughing a bit. It’s telling that none of them grew up Orthodox. Yeshivas were prepared to deal with celebrities hundreds of years old—the Baal Shem Tov, Rav Nachman of Breslov, Rashi. We were taught that every generation away from the reception of the Ten Commandments is spiritually weaker than the one before it, just by virtue of being born later. The idea that an Orthodox Jew—a real Orthodox Jew, one who passed all the imaginary tests by those looking for authenticity—could grasp onto a new idea was not one for which we prepared.

The copies of Matisyahu’s debut, Shake Off the Dust… Arise, metastasized in hallways. Describing how he made the album was one of the few moments during our talk when Matisyahu sprang to life. He knew at the time he was creating something new: “It was like, taking the roots-reggae thing and connecting it with all the elements of this Chabad Hasidish knowledge,” he said. “It was a very fun project. It was my first creative outlet after being in Yeshiva for a long period of time.”

Everyone at my yeshiva had heard Jewish religious music, of course. To enjoy it was to take your place within a grand tradition, one that had come before you and would be there after you leave. It was also a little lame, something to be enjoyed only if fenced off from the rest of your life. Back in 2004, when it came out, Shake off the Dust felt vital, sudden, important—to us, at least. On a track like “Warrior,” a seven-minute jam that never loses its focus, Matisyahu’s voice is a multifaceted diamond. Rap, expressions of spiritual desire, beat-boxing—any musical element he could mine shines, gorgeously. There was a bluntness in the spirituality of a song like “Chop ’Em Down,” but also a deep sense of mystery—“from the forest itself comes the handle for the ax,” he sang, as ska-style horns sway in the background. Keyboards lightly clear a path for his booming voice, a guitar is picked with lazy determination. If you listened enough, eventually, you thought, you could get on his level, whatever that was.

But the 2005 album Live at Stubb’s is the thing from which we’re still feeling aftershocks. “While Shake Off the Dust… Arise had its dreamy, mystical, and more relaxed side, Stubb’s is filled with rousing energy,” wrote AllMusic’s David Jeffries, and he was right. Stubb’s has multiple seven-minute tracks, and there’s barely a wasted moment, and never one that doesn’t seem to be working toward a greater whole. The live Stubb’s version of “King Without a Crown”—initially off of Shake Off the Dust—is the one that became a massive radio hit, reaching No. 28 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 7 on Billboard Hot Modern Rock Tracks. (“Hot” and “modern” had rarely been used in relation to “Orthodox.”) A shorter studio version of it was then placed on Matisyahu’s second studio album Youth and as a BestBuy Exclusive you could also buy the song remixed by Mike D of the Beastie Boys, which begins with Mike D yelling “Matisyahu, y’all!” Videos were made for both the live and Youth versions of the song, and the song soon got overplayed.

The live video for “King Without a Crown” gets across the energy of Matisyahu’s rise. The location was perfect—recorded in Austin, Texas, of all non-Jewy places, in February 2005. “With these demons surround all around to bring me down to negativity,” he raps, before puffing his chest, back when he wore a long beard and glasses. “But I believe, yes I believe, I said I BELIEVE!” He stage-dives into the crowd, heedless of the fact that, you know, women might touch him while doing so. At a time when high school was getting more and more oppressive, and later, in those lonely early months of college, I’d do my best to try to channel the freedom I had seen in the “King” video.

For me, and for legions of fans, Matis became a symbol, and if there’s one thing Jews love, it’s symbols. Rabbis started singing his songs in the halls, happy to tell you the hidden references to spiritual texts within them if you approached, as if RapGenius was actually Talmudic. Among the Haredi students and others, bragging rights were granted Six Degrees style—did your rabbi house Matisyahu on his West Coast Tour? Did you know someone who davened with him? Did you actually pray with him yourself?

***

As I got older and less religious, Matisyahu meant less and less, but his music refused to let go. In college, I’d make sure my roommate had left for class before I’d blast Youth, which came out in March of 2006. I would dig through my stores of uncool clothing to find the yarmulke my mother had made me pack. I’d put it on and listen to “Jerusalem,” my distaste for the Israeli government be damned. The album branches out musically—the eponymous single has a touch of metal; “What I’m Fighting For” is quiet acoustic—and, like Stubb’s, went gold, which probably (and I’m guessing here) is what led studio execs to push through that fourth mess of an album, Light.

Delayed several times due to aggressive touring and Matisyahu constantly adding new songs, Light has the feel of an album that can’t make up its mind. The album’s final track, the solemn and yearning “Silence,” wouldn’t sound out of place coming from Bon Iver, but paired with the overly saccharine hit “One Day,” none of it makes sense. Partially written by Bruno Mars, “One Day” was referred to by The Onion’s nonsatirical AV Club as “pure Velveeta, or whatever it is they smear on crackers where Desmond Dekker’s progeny and actual Israelites frolic in harmony.” Was it bad enough that it begged for a clean slate? Is that what led Matisyahu to shave his beard? The timing makes it plausible: In the three years between “One Day” and the Beardshaving, Matisyahu stuck to releasing small live EPs and a sequel to Stubb’s, Live at Stubb’s II. When he finally made headlines again, those who weren’t personally invested in Matisyahu’s identity shrugged, or worse. “Matisyahu Shaves Beard, Reminding World of His Existence,” laughed Gawker.

Seven months later, instead of back-to-basics, or back-to-whatever, we got Spark Seeker, which fully embraces the electro-sheen that had started to find its way into Matisyahu’s work a few albums back. It’s got one-time Diddy collaborator and current Orthodox Jew Shyne on it, because it was only a matter of time before Matisyahu and Shyne did something together. The album’s lyrics are mostly boilerplate about being optimistic, with a few auto-tuned spiritual asides. If you ever wondered if you could sit through an auto-tuned sermon, as happens on “Searchin’ ” without laughing, it’s possible after about six or seven listens, after which you just start to feel sad.

Like Kabbalah in the 1990s, Spark Seeker seems to have taken what was unique about Matisyahu’s voice and watered it down behind whatever is popular these days. That might not have been the intention, but it sure worked. Debuting at No. 19 on Billboard with first week sales of 16,000, it’s still hanging around the Reggae charts 57 weeks later. Listening to it, you’d be hard-pressed to find anything that resembles Marley or Dekker or current reggae stars like Protoje—and it’d be very hard to tell Matisyahu not to keep doing whatever it is that he’s doing so well.

***

Back in Morristown, Matis-discovered opener Levi Robin did his singer-songwriter thing. His voice was gorgeous, his songs earnest and plain—he sounded as if a Mumford Son had gone on Birthright and never looked back. Matisyahu had been hyping Robin a lot on Twitter. Robin’s most interesting moment came, Marco Rubio-style, when he took a sip from a bottle of water. He said the blessing for it, shehakol, and was met with nervous laughter, then applause. The laughers seemed mildly shocked that someone on a stage could be saying the blessings that they say in their day-to-day lives, until they remembered this was a Matisyahu show. The sold-out crowd of 1,300 at the Morristown MPAC, known locally as the Community Theater, was by my estimate half Orthodox and half not-Orthodox. Whole families sitting down, up to and including grandparents.

As Matisyahu and his band came out, two things were clear—the first was that the “acoustic show” billing referred to the fact that there was an acoustic guitar present. The second was that his voice is a booming wonder. It rose in a way that voices do when they’re alone. When he launched into “Crossroads,” which opens Spark Seeker, it’s Acoustic counterpart, and at least the Morristown show, the room suddenly felt very small. “I’m still young/ Having mystic visions of The One,” he declared-slash-humblebragged, seated on a chair onstage. “All I got is my life/ All I got is my life!”

After “Searchin’,” a rambling feel took over the band, which included Dave Holmes on the aforementioned acoustic guitar, channeling that old Matisyahu influence, Phish. This was followed by the Stubb’s classic “Exaltation.” I looked around several times, to see if my fellow seated concert-goers were into this seemingly bland, watered-down version of songs we’d heard before. They were, big time, at least the seated version of big time, kind of just moving around in place a bit, not really sure of what to do but wanting to avoid the embarrassment of sitting down mid-song in front of the whole crowd. Many were mouthing the words out loud—“it’s time for a champion/ To heal the soul of the land.” The energy was high, the entire audience focused on Matisyahu, and if he had only stood up he’d have commanded the crowd. He got close, stretching his back at one point.

But what about that conversion—or that shaving incident, or whatever it was? Earlier in the evening, I’d been given 10 to 15 minutes with the man in his tour bus, and I wanted to know about his religious choices. Matisyahu the artist had moved away from his early fire toward a popular sound that carried only the shadow of his original message, and in doing so he became neither unique nor particularly disturbed. “I remember the moment when it hit me,” he told AISH last year, around when Spark Seeker was being released. “I was walking down Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side, and it felt like I was literally walking out of a jail cell that I had been in. At that moment I realized I could shave if I wanted. It was up to me and no one else.” So now, a year after the razor, what did he make of it? Matisyahu laughed and called it “the beard charade”—he knew it might be the last time Matisyahu breaks into the cultural consciousness. “I can speak about it, I can tell you,” about the beard shaving, he said to me. “In a certain way, my growing of and shaving of the beard had a similar meaning.”

We moved into a small discussion about the differences between spirituality and religion. “I think they are two things that don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand all the time,” he said. “For the most part, in today’s society, we’re all witness to see how religion has had such a strong negative impact on the world and citizens of the world. So, the majority of people are very skeptical of religion, even if religion is something that can contribute to the world being a more spiritual place.” Religious rules had given him “a certain structure” when he was younger, and now that he was a grown man some of those arbitrary laws seemed kind of silly, he said, so he didn’t follow them.

Matisyahu the artist had moved away from his early fire toward a popular sound that carried only the shadow of his original message

How did his religious fans react to this sort of message? Near the end of the Morristown concert, Matisyahu stopped the music to see if anyone had any questions, a freebie before an exclusive $100 meet-and-greet scheduled for after the show. He had been doing Q&As during shows, and a few days before Morristown he had told CT.com, “I don’t feel pressure, I don’t pretend to be a teacher or something.” I was excited, with the hope that some of these fans could get a solid answer out of the cipher I had met earlier. One asked when he would be playing Argentina next, another if he knew what an inspiration he was. Then another stood before a mic in the aisle and laid in.

“All your songs are great,” he said, though he clearly did not believe all of Matisyahu’s songs are great. “And you get to notice that you have two different types of songs. Now, they’re all great. But your religious songs, they have this extra fire in them. Why do you think that is?” Matis, very chill, looked at the man. In the wake of the shaving incident, Matisyahu had said pretty much the same thing about religion for over a year now, telling Timeand Heebthat you can be spiritual without being religious. In Morristown he said, “I don’t see a difference between the two. You can find that type of fire wherever you look.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Meir Grossman is a writer living in Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @davidgross_man.

David Meir Grossman is a writer living in Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @davidgross_man.