‘The Museum of Extraordinary Things’ Is Extra Ordinary

In her latest novel, Alice Hoffman renders the brutal world of Lower East Side immigrants in the romantic hues her readers expect

Today, the building at 23 Washington Place in Manhattan, just off Washington Square, is known as the Brown Building, and it is part of NYU’s ever-growing Greenwich Village empire. But in 1911, it was called the Asch Building, and its eighth, ninth, and 10th floors were occupied by a sweatshop called the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, where some 500 workers, mostly young Jewish and Italian girls, produced women’s blouses. When fire broke out there on March 25 of that year, nearly 150 workers died, in part because their bosses had locked the exit doors from the outside. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was the deadliest disaster in New York City until the collapse of the World Trade Center 90 years later.

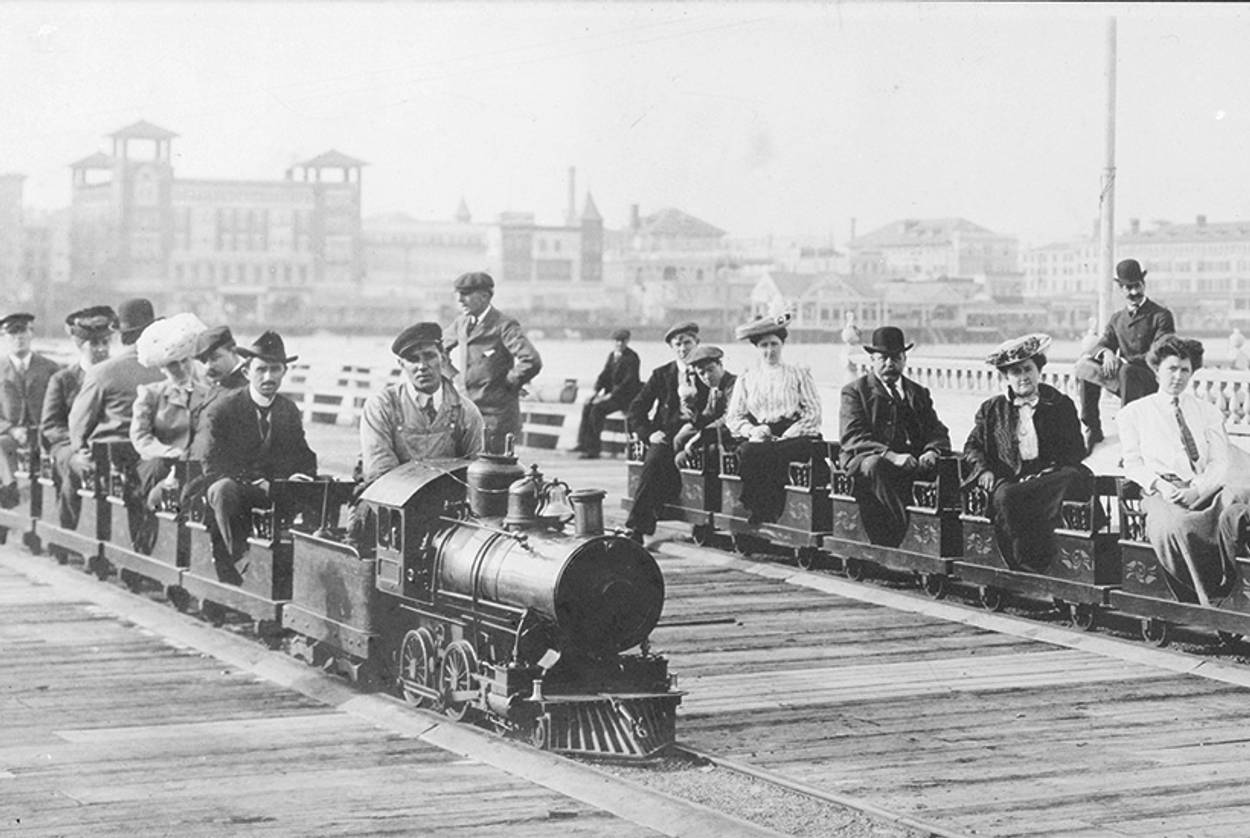

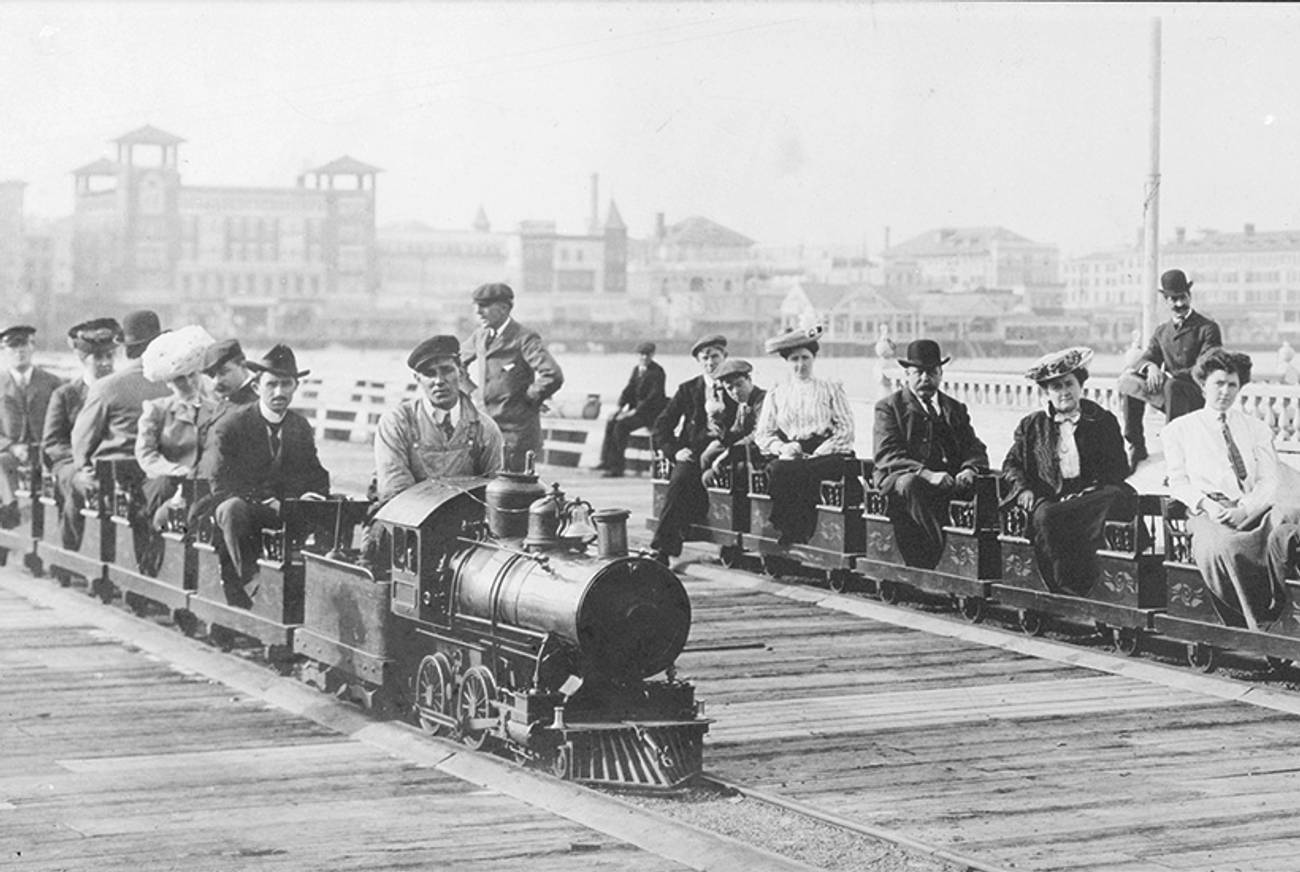

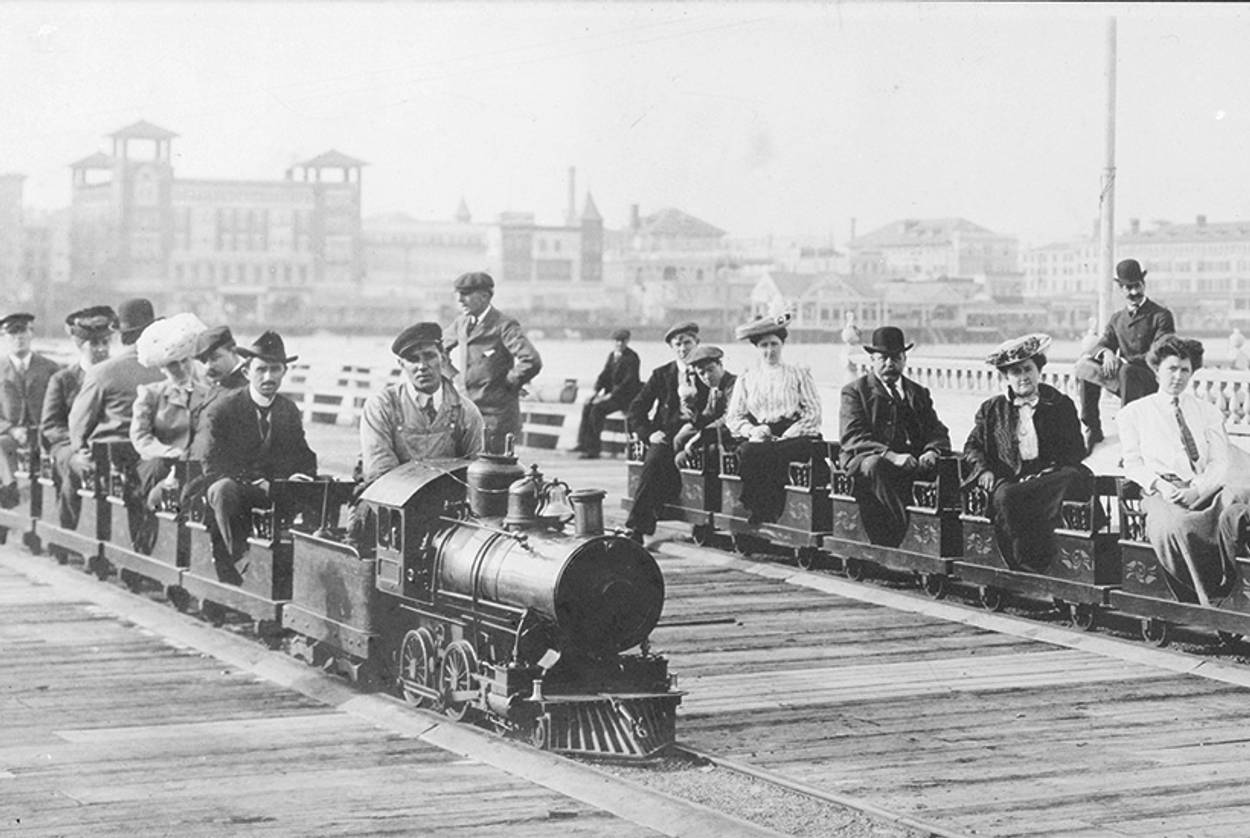

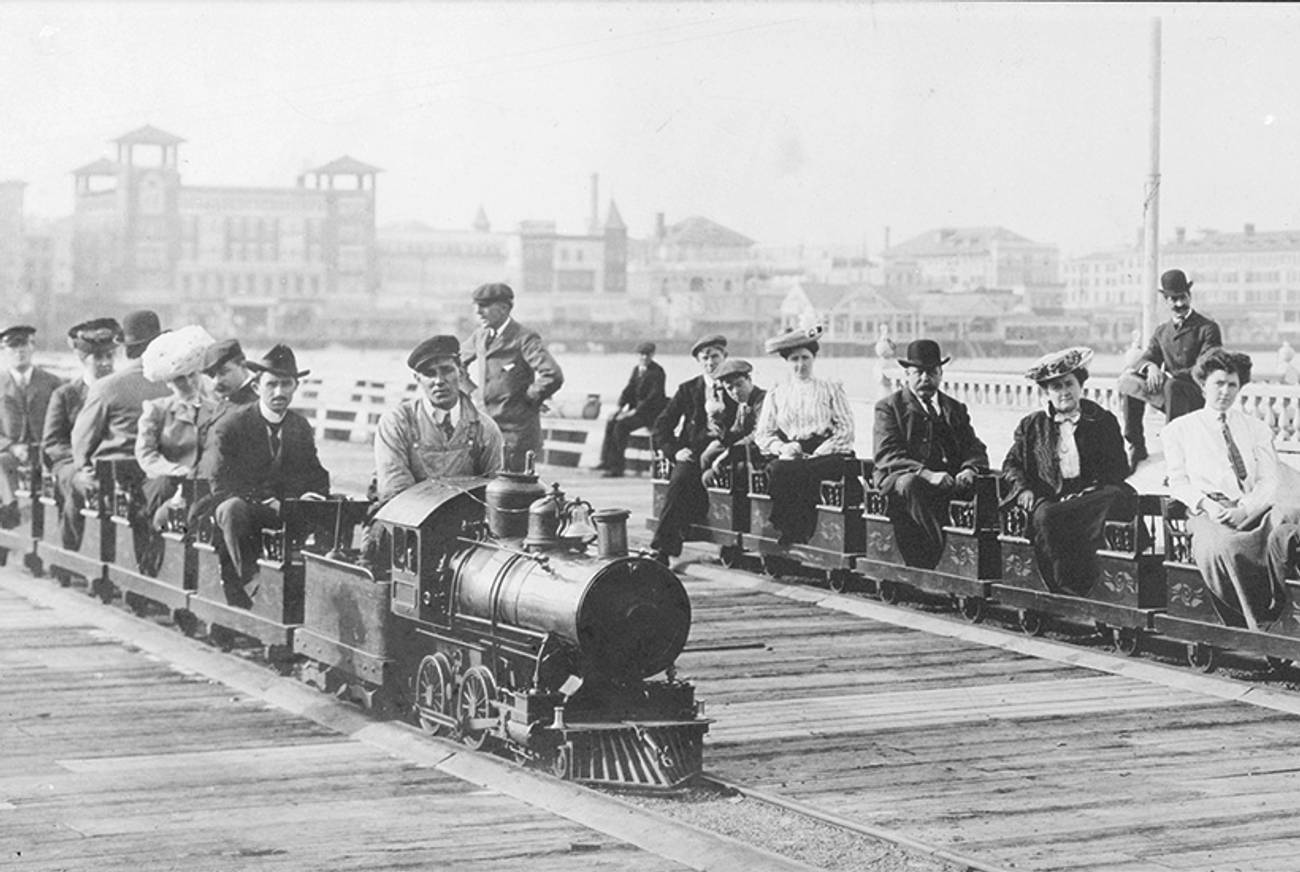

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was not the only great conflagration to shake New York City in 1911, however. Just two months later, on May 27, the Coney Island amusement park Dreamland caught fire and burned to the ground, after workmen preparing for the summer opening accidentally knocked over a pail of boiling tar. This blaze, while big enough to incinerate blocks of Coney Island and call out firemen from all over Brooklyn, claimed no human victims, which is why it is so little remembered today. Instead, it killed the dozens of wild animals who were part of Dreamland’s menagerie, including a lion and an elephant. One of the strangest exhibits at the park was a demonstration of incubators for premature babies, then a new invention; happily, all the babies were rescued.

None of the extraordinary things in The Museum of Extraordinary Things, the new novel by Alice Hoffman, beats the true stories of those two fires. Set in New York in the first half of 1911, with flashbacks to the previous decades, Hoffman’s novel is bookended by vivid set-piece descriptions of the disasters. A New Yorker herself, she describes the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire using images that invoke the iconography of Sept. 11. The parallel is doubtful in some ways—Sept. 11 was an attack, not an accident, and the casualties were worse by several orders of magnitude—but the vision of falling bodies is something both disasters had in common:

Girls had begun to leap from the windows of the ninth floor, some embracing so they might spend their last moments on earth in each other’s arms rather than face their fates alone. Some jumped with their eyes closed, others with their hair and clothes already burning. At first, the falling girls had seemed like birds. Bright cardinals, bone-white doves, swooping blackbirds in velvet-collared coats. But when they hit the cement, the terrible truth of the matter was revealed. Their bodies were broken, dashed to their deaths right before those who stood by helpless.

There is an uneasy tension in this passage between the bird image, with its soothing prettiness, and the reality of falling bodies, which Hoffman also captures—pointing out, for instance, how the jumpers broke through the life-nets stretched out for them and crashed through the sidewalk, ending up in the basements underneath. That same tension, between the desire to capture a brutal world and to render it in the hues of romance and make-believe, pervades The Museum of Extraordinary Things. Hoffman is a prolific and popular writer—her best-known novel, Practical Magic, was turned into a movie; another book was an Oprah’s Book Club choice—and she uses the formulas of popular fiction skillfully. But that skill often means giving readers what they want, even at the expense of probability and realism. Even as her story is built around murder, sexual abuse, exploitation, and misery, she fills it with reassuring coincidences and consolations. No matter how many people suffer along the way, we know from the first that the hero and heroine are guaranteed a happy ending.

Before they get there, however, Hoffman offers an impressively disillusioned account of one of the most sentimentalized parts of American Jewish history: the life of immigrants on the Lower East Side around the turn of the 20th century. Her own ancestors, Hoffman writes in an author’s note, were part of that immigrant world—“one began his working life in a pie factory at the age of twelve”—but she does not see it as the beginning of a great American adventure, or as a homey place full of tradition and community.

Instead, we see the Jewish Lower East Side through the eyes of Eddie Cohen, who barely survives a childhood of Dickensian poverty. After losing his mother in a pogrom in the Ukraine, Eddie—originally called Ezekiel—and his father make their way to America, where they are barely better off. The defining episode of Eddie’s young life comes when his father, laid off from a sweatshop, jumps into the Hudson River rather than keep on struggling. He survives, but from that moment Eddie despises him, and the boy decides that success in America requires looking out for number one, whatever it takes.

“After that I avoided people in our neighborhood,” Eddie recalls in one of the first-person chapters interspersed through the book. “I no longer considered myself Orthodox, and I left my hat under the bed whenever I went out alone. … I had become someone else, but who was that someone?” As it turns out, Eddie becomes an assistant to a neighborhood con man named Hochman, and then an apprentice to a kindly photographer, Moses Levy. It is as a news photographer that he is called to the scene of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, becoming the reader’s eyes and ears on the tragedy: “Eddie did his job, but as he photographed the fallen he had the sense that he was standing at the end of creation.”

To be an immigrant in America, Hoffman suggests, especially a Jewish immigrant fleeing persecution, means struggling to create a new identity while leaving behind a piece of one’s soul. Hardened by his experiences, Eddie becomes a kind of Humphrey Bogart hero, sullen but sensitive, clearly in need of redemption by a good woman. When the father of a girl who disappeared in the Triangle fire hires Eddie to find out her fate—did she die in the blaze, or escape, or fall victim to foul play?—the resemblance to Philip Marlowe becomes even closer.

Happily, the other narrator whose voice we hear in The Museum of Extraordinary Things is a good woman waiting for a rescuer. Coralie Sardie lives in the dark shadows of another frequently idealized part of New York, Coney Island in its heyday. She has grown up on the grounds of the titular museum, which is actually a boardwalk freakshow, featuring wolfmen, butterfly girls, and fetuses in jars. Her father, a sinister tyrant known as the Professor, even forces Coralie to perform as a mermaid, inspired by the fact that she was born with webbed fingers. As she gets older, her act in a water tank becomes something more like a sex show—an experience that humiliates Coralie and fits in with Hoffman’s portrait of 1911 New York as a giant theater of female exploitation, from the girls in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory to the prostitutes on the street.

Fearing competition from Dreamland, which threatens to put his small-time attraction out of business, the Professor comes up with a new scheme. He forces Coralie to swim around Manhattan dressed as a sea creature, in order to drum up newspaper reports of a local monster. In Hoffman’s telling, these swims reveal Coralie’s spiritual affinity for the water and give her a taste of freedom: “I fell in love with the Hudson; because of the nights I swam there, I no longer was forced to perform, and so I began to think of the river as my savior.”

On one of these trips, she stumbles across the corpse of a young woman, which the Professor quickly confiscates. His plan is to turn the dead body into a half-human, half-fish through horrible surgeries, then display it as the rumored sea-monster. But Coralie, appalled by the idea, begins to rebel against her father’s iron discipline, to the point of invading his workshop and reading his secret diary. There she discovers that everything she knows about her past is a lie, and that the Professor is, if possible, even worse than he appears.

In time, the novel confirms what the reader has already figured out, that the dead girl Eddie is looking for and the dead girl Coralie finds are one and the same. In this way, their paths finally cross, and each finds in the other the freedom they seek: Coralie’s liberaton from her father and the sordid world of the freakshow, Eddie’s liberation from loneliness and alienation and resentment. But will they be able to overcome the opposition of the ruthless Professor? Will Eddie solve the mystery of the girl’s death, and get revenge on whoever caused it? Will Eddie’s loyal pitbull Mitts survive the Dreamland fire, which is the climax of the novel? The answers will not surprise the reader used to the conventions of popular fiction, or Hollywood movies. But The Museum of Extraordinary Things offers a picturesque journey, and sometimes even a disturbing one, on the way to its foreordained happy ending.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.