In November 2014, I spent five very full days in Moscow. I divided my schedule into blocks of research, lectures and bookstore talks, and some downtime in the city that used to be my home. Every time I travel back to Russia, I say to myself that this may very well be the last trip. And indeed, that particular homecoming was studded with complications from the moment I got off the plane at Sheremetyevo.

At passport control, a bored junior officer first asked me for proof that I had emigrated from the USSR prior to 1991 (I readily presented a copy of my 1987 exit visa to Israel), then inquired if I had any connections to “intelligence services.” Finally, he claimed that the Russian visa in my U.S. passport had “a problem.” The issue was finally resolved when I asked to speak with the “shift supervisor” (whatever that means in the world of border patrols) and showed him a flyer for my book event at one of Moscow’s largest bookstores. “It’s tonight,” I said, feeling exasperated. “I came here to speak about two great Russian writers, Bunin and Nabokov. Have you heard about them?” The captain in charge waved his hand and let me into the country.

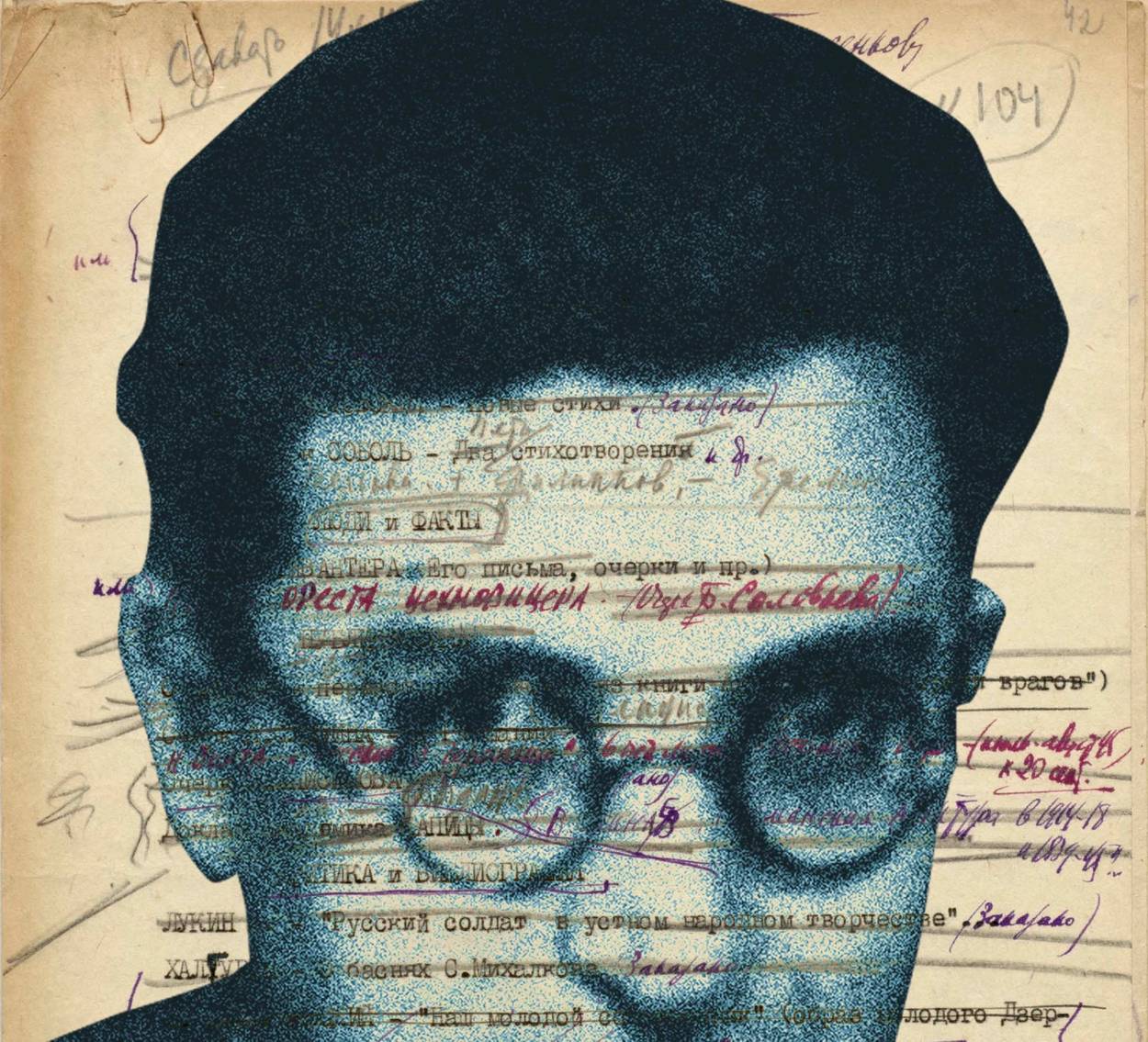

I traveled to Russia to conduct research for a book about Jewish-Russian poets as witnesses to the Shoah. Among my main characters was Ilya Selvinsky (1899-1968), the Crimea-born poet and playwright. A descendant of Ashkenazi Jews and Krymchaks, Selvinsky was a poetic virtuoso, a visionary of Soviet constructivism in the 1920s.

In 1942, as a frontline journalist, Selvinsky became the first Soviet national poetic witness to the systematic murder of Jews by Nazis and accomplices in the occupied Soviet territories. I wanted to see the manuscripts and typescripts of some of the texts I was writing about—mainly to rule out major discrepancies between the originals and the published versions.

The Russian State Archive for Literature and the Arts (RGALI), which was my destination, is a mecca for literary research. A minor textbook example of the Stalinist Empire style, this five-story building with a classical fronton, laid in yellow stone, stands in a residential neighborhood in Moscow’s northwest sector, a short walk from Water Stadium metro station. My day at the archive did not start well. The head of circulation, a man in his 30s who looked like an Orthodox seminarian bent on political terrorism, made every effort not to facilitate my work. Finally, around noon, the three folders I most wanted to see were before my eyes in the reading room. They contained Selvinsky’s poems from the 1930s and ’40s, including his most famous poems about the Shoah: “I Saw It” (1942), “Kerch” (1942), and “Kandava” (1945).

As I leafed through the folders, taking preliminary notes, I came across two drafts of a poem titled “Sud v Krasnodare” (“The Trial in Krasnodar”), one typed on long sheets of cigarette paper with tiers of editing in fountain pen and pencil, and another typed on yellowed newsprint paper with typed sections glued over earlier text and some corrections in Selvinsky’s hand. Published in 1945, this poem just shy of 300 lines, mostly of blank iambic pentameter, depicts the first trial of Nazi collaborators that took place in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar (formerly Ekaterinodar) on July 14-18, 1943. For the students of the Shoah in the Soviet Union, the 1943 Krasnodar Trial is significant for giving shape and expression to the then recently crystalized Stalinist doctrine of universalizing the Soviet dead and obfuscating Jewish victimhood.

A text of great historical importance, “The Trial in Krasnodar” is not among Selvinsky’s finest works. It had always fascinated and repelled me with its anguished diction—as though the poet had composed it while being slowly choked. As I read through the two drafts, I immediately knew it was not the poem I remembered from its published version. In both archival drafts, unlike the published text of 1945, a public execution of collaborators was described in vividly graphic detail. And in both drafts, a character by the name of “Tolstoy” played a major role.

Tolstoy, really? I was overcome by a combination of shock, wild curiosity and desire to know more.

At the 1943 Krasnodar Trial (not to be confused with the October 1963 Krasnodar Trial, of which Lev Ginzburg wrote in his book Abyss), 15 Nazis were named by the prosecution. Those included the commander of the 17th Army, Colonel General Richard Ruoff, the commander of Sonderkommando 10a SS Sturmbannführer, Dr. Kurt Christmann (subsequently tried in Munich in 1980), and two military physicians.

However, at Krasnodar’s cinema house Velikan (“Giant”), the city’s largest standing auditorium that operated during the occupation, only Soviet citizens stood trial. Of the 11 accused, 10 were ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, one an ethnic Adyghe; five were natives of the Krasnodar Region. Most of them had been auxiliaries of Sonderkommando 10a of Einsatzgruppe D. Although their roles in the execution of genocidal crimes during the occupation of the Krasnodar Region varied from being members of the killing squads to rendering logistical assistance during the roundups of Jews and Communists, all 11 were tried by a military tribunal of the North Caucasus Front and charged under the omnibus “counterrevolutionary action” article 58-1 (paragraphs a and b) of the Penal Code of the Russian Federation.

In the proceedings of the trial, their crimes were described as those of “accomplices” (posobniki) to Wehrmacht and SS officers. I quote from the verdict (the literal translations of Russian sources are my own): “in the course of over six months [the named Nazis] jointly with their accomplices—betrayers and traitors of our socialist motherland Tishchenko V., Rechkalov I., Misan G., Lastovina M., Pushkarev N., Tuchkov G., Paramonov I., Natspok Yu., Kotomtsev I., Pavlov V., and Kladov I., through various beastly methods were annihilating the civilian population of the city of Krasnodar and the Krasnodar Region. The Hitlerite monsters and their above-named accomplices shot, hanged, suffocated by means of the poisonous carbon monoxide gas and tortured to death many thousand innocent Soviet people, among them women, elderly and children.”

Eight of the accused were sentenced to death by hanging, and three to 20 years of katorga (hard labor). Immediately upon the conclusion of the trial a public execution took place at Krasnodar’s main square, with some 30,000 people, including children, watching and applauding.

The hanging was hyper-realistically captured in the short documentary, The Verdict of the People, released in August 1943.

The word “Jew” appears to have sounded only once throughout the trial proceedings. One of the witnesses, a doctor at a local hospital, described how a Nazi doctor with a group of officers gathered the entire medical personnel and asked, in broken Russian: “Communists, Komsomol members, Jews?” The Nazis were allegedly told that there were no “Communists, Komsomol members, Jews,” though it was not clear from the deposition whether they had already been taken or the medical personnel deliberately refused to volunteer the information. The witness then proceeded to describe how the Nazis took a group of hospital patients and forced them into a mobile gas van.

The 1943 Krasnodar Trial was a carefully choreographed performance, with the accused confessing their crimes but omitting the identity of the people whom their crimes had principally targeted; with the state prosecutor acting the role of a Soviet Themis clad in a military jurist’s tunic; with official guests knowingly posing for the camera; with members of the audience, most of whom had just recently looked the other way as their Jewish neighbors were being annihilated, now donning expressions of hatred for the 11 men sitting in the dock under armed guard.

The accused during the Krasnodar Trial, July 14-18, 1943; still from ‘The Verdict of the People’ (1943)Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

Stalin took a special interest in the trial. Besides Vyacheslav Molotov and Andrey Vyshinsky, who were charged with the preparation of the proceedings, and State Prosecutor Viktor Bochkov, who was nominally responsible for laying out the charges, Stalin’s trial team included Georgy Aleksandrov, head of the Directorate of Agitation and Propaganda of the Central Committee of the Party. Aleksandrov was one of the creators of the official Soviet rhetoric of nonspecifying both Jewish death by the hands of the Nazis and their collaborators and Jewish battlefield valor.

Before we follow the reporters into the courtroom where the Krasnodar Trial opened 77 years ago today, some background about the occupation of the region and the coverage of the trial is in order. The city of Krasnodar was under German occupation for 186 days, from Aug. 9, 1942, to Feb. 12, 1943. Prior to World War II only 7,600 Jews had resided in the entire Krasnodar Region—the historical area of the Kuban Cossack Host had not been a place of rich Jewish life. According to Soviet evacuation data, as of October 1941, 218,000 people, 160,000 of them Jewish (73%), had been evacuated to the region. Some 36,000 evacuees from Leningrad alone were received in the Krasnodar Region. More people were evacuated in spring and summer 1942, especially from Crimea, Rostov Province, and Leningrad Province. During the occupation of the Krasnodar Region, of its 78 districts and 12 cities, only four districts and three cities were not occupied.

Between 18,000 and 27,000 Jews were murdered in the region’s 65 cities, towns, Cossack villages (stanitsas) and other rural settlements in the late summer and autumn of 1942 by units of Einsatzkommando 11 and of Sonderkommando 10a, which were in charge of the killings of Jews and Roma in the region. Four major killing centers/sites are distinguished by large numbers of victims: the region’s capital, Krasnodar, with over 3,000 murdered Jews, and three smaller communities with perhaps 3,000 or more victims murdered: Belaya Glina, Petropavlovskaya (Kurgannaya District), and Ladozhskaya (Ust-Labinskaya District). About 75% of the Jewish victims were killed within the first two months of the occupation in August-September 1942. In the words of the Moscow-born Israeli historian Kirill Feferman, a leading authority on the Shoah in the occupied Caucasus, Crimea and southern Russia, “the Jewish population was overwhelmingly made up of newcomers to the region, or to borrow today’s language, refugees.” The victims included a high proportion of Jewish children, also mainly evacuees, among them wards of orphanages. The killing methods included not only firearms but also mobile gas vans (known in Russian as dushegubki, literally “souldestroyers”), which came to public attention in connection with the trial.

Starting with the spring of 1943, and throughout the summer and autumn—both before and after the Krasnodar Trial—Nazi crimes were investigated by the Extraordinary State Commission for Ascertaining and Investigating Crimes of the German-Fascist Invaders and Their Accomplices (ChGK), by the Krasnodar Regional Commission, and by local district commissions. The documented findings of local investigations consistently reflected the systematic murder of Jews. The brief report on the Krasnodar findings of the Extraordinary State Commission, published at the start of the trial, spoke of thousands of Soviet citizens murdered by carbon monoxide, of thousands of corpses of Soviet citizens dropped into antitank ditches, yet made no mention of Jews.

According to prevalent Soviet and post-Soviet Russian data, over 52,000 civilians and over 9,000 Soviet POWs were murdered during the occupation of the Krasnodar Region, almost 7,000 in the city of Krasnodar. When I queried Feferman about the data on both the evacuees and murdered Soviet citizens in the Krasnodar Region, he replied: “Practically the whole statistics of the Holocaust in Soviet territories are murky waters. … My sense is that the clearly bloated estimates of the number of murdered civilians in the Krasnodar Region were first sounded back in 1943 in connection with the Krasnodar Trial. … And subsequently, after the number of victims had entered the [Soviet] canon, it was no longer possible to revise it.”

The 1943 Krasnodar Trial was meant to deliver a clear-cut nationwide message that Nazi collaborators would be punished. At the same time, the trial sought to present the collaborators as outcasts and abominations, people bearing a grudge against the Soviet system—not as a common occurrence in occupied Soviet territory. Furthermore, the trial deliberately obscured the targeted anti-Jewish nature of Nazi atrocities—a tall order to carry out as the Red Army was about to liberate large swaths of Nazi-occupied territory.

The timing of the trial was fortuitous for propaganda purposes. On July 12, 1943, two days prior to the opening, Red Army forces had commenced Operation Kutuzov, aimed at the defeat of the Nazi troops at the Oryol salient. The forces of Soviet wartime journalism, including three of its biggest stars, were writing about the Soviet offensive and the fighting at Oryol-Kursk-Belgorod. As we scrutinize the roster of those who covered the Krasnodar Trial, a crucial fact emerges. No Jews with a national reputation reported on the trial for leading newspapers and magazines such as Red Star, the main Red Army newspaper, or Pravda, the party’s central organ.

Among the major writers not present at the 1943 Krasnodar Trial were Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman. The summer 1943 publications of Ehrenburg, the peerless voice of Soviet anti-Nazi propaganda and the founding editor of the Black Book project created to document the murder of Jews by Nazis in occupied Soviet territories and death camps, did not mention Krasnodar. In July 1943 he wrote about La Résistance in occupied France and the future of liberated France as an ally against Nazism and also reported on the Soviet military offensive. Throughout July 1943, Grossman contributed one long article, titled “July 1943,” based on his frontline reporting from the Oryol and Belgorod-Kursk directions. The job of covering the trial went to Aleksey N. Tolstoy (1883-1945), a particularly talented yet venal figure from the top echelon of Russian Soviet writers.

Aleksey N. Tolstoy, left, and the military journalist Nikolay Denisov, 1943Courtesy Maxim D. Shrayer

The absence of Soviet Jewish stars of wartime journalism at the trial corresponds with the paranoid logic of a Stalinist wave of cleansing that was already rising in the summer of 1943. Joshua Rubenstein, Ehrenburg’s American biographer and author of The Last Days of Stalin, notes the changing climate: “Stalin moved to diminish official concern about Jews. … Ehrenburg sensed this change. His articles began to be heavily censored, particularly when he wrote about Jewish martyrdom and heroism.” Boris Lanin, a leading scholar of Vasily Grossman and author of a series of literature textbooks recently banned in Russia, believes that in the summer of 1943 Stalin’s regime wanted not only Sovietly universalized Jews among the country’s dead but also invisible Jews on its front pages and frontlines. In an interview, Lanin told me that “Stalin’s regime could hardly tolerate open Jews reporting on the first trial of (mainly Russian) traitors and collaborators.”

Which brings us back to the writer trusted and handpicked by Stalin’s leadership to report on the Krasnodar Trial: Aleksey N. Tolstoy, scion of an old aristocratic family and a Russian count by birth.

A gifted fiction writer in the history of Russian and Soviet letters, Aleksey N. Tolstoy (not to be confused with his distant cousins, the great Leo Tolstoy and the 19th-century poet and historical novelist Aleksey K. Tolstoy), is known as “the third Tolstoy.” Having returned from emigration to the Soviet Union in 1923 to become one of the country’s preeminent authors, Tolstoy zestfully distorted the historical facts of the Russian Civil War and contributed to the emerging cult of Stalin’s personality. By some accounts Tolstoy was not a friendly observer of Jewish life and death—despite or because of a previous, unresolved marriage to the Jewish-Russian artist Sofia Dymshits.

For a week in the middle of July 1943, information about the Krasnodar Trial crowded the pages of Soviet newspapers in the form of editorials and summaries of the proceedings based on the reports of TASS, the Soviet news agency.

Yet the original coverage was unremarkable except for the gripping photos of exhumed bodies. Daria Sadovnichenko, a young researcher from Moscow who is pursuing graduate study in Boston and assisted me in this investigation, thus summarized her observations of perusing complete runs of major Soviet newspapers for the spring and summer of 1943: “I could not but notice a very persistent line that the state was pursuing through the reporting and editorials: there is pure evil—German occupants and their collaborators […], and Soviet liberators and Soviet people [fighting against them]; [the coverage leaves] aside the question of Jewish death and victimhood. … The Soviet newspapers created the image of the rightful thirst for revenge that would justify any measures needed by the country.”

Alongside Aleksey N. Tolstoy, sometimes sitting right beside him, was another famous Soviet writer, the poet Ilya Selvinsky. From August 1941 until November 1943 Selvinsky was a military journalist and political officer fighting in Crimea, North Caucasus, and on the Black Sea coast.

Selvinsky’s experience as a witness to the liberation of Krasnodar differed drastically from his experience in eastern Crimea in early January 1942, where, west of the city of Kerch, Selvinsky saw the Bagerovo antitank ditch filled to the brim with bodies, almost all of them Jewish women, children and elderly.

The sight of this open-air morgue changed Selvinsky’s life and informed the creation, in 1942, of two major Shoah poems, “I Saw It” and “Kerch.” It is unclear how much Selvinsky saw of the aftermath of Nazi atrocities during the liberation of the Krasnodar Region. Prior to July 1943, Selvinsky had been to the city of Krasnodar and throughout the region with the troops of the North Caucasus Front. His diary for the spring of 1943 documents the liberation of Krasnodar yet contains no mention of Jewish victimhood. Between May and October 1943 there is a gap in what survives of the red-bound notebook Selvinsky used as his wartime diary.

Even though Selvinsky was technically accredited as a Red Star correspondent, he came to Krasnodar as a staff writer for the main newspaper of the North Caucasus Front. His wartime career had entered a downward spiral, and one day prior to the opening of the trial a denunciatory anonymous article against him appeared in Izvestia.

Not for the first time, Selvinsky had run into major trouble with Stalin’s leadership. This time the reprisal had to do with Selvinsky’s wartime writings and, specifically, his double-voiced, Jewish-Russian perspective. He arrived at the trial with Aleksey N. Tolstoy and was often seated close to the renowned Soviet air force pilots Dmitry Glinka and Aleksandr Pokryshkin. And yet he was not once mentioned in the coverage of the trial. He appears in the raw documentary material filmed at the trial but was cut with remarkable precision—almost frame by frame—out of the documentary film released after the trial. Selvinsky published no reports of the trial in his frontline newspaper Vpered k pobede! (Forward to Victory!), and no archival evidence suggests that he filed any.

Aleksey N. Tolstoy was present at the trial not only as a famous writer but also as a member of the Extraordinary State Commission. In fact, in advance of his trip, Tolstoy was handed a detailed investigative report about the use of mobile gas vans, submitted back in February 1943 but held back and unpublished. His performance as the government-chosen reporter was perplexing. Eyewitness accounts indicate that Tolstoy did not stay to observe the public execution and left after the reading of the verdict. He did not write anything about the trial, either for the central civilian newspapers or for Red Star.

According to the memoirs of Major General David Ortenberg (Vadimov), who at the end of the summer of 1943 was replaced as editor of Red Star with Major General Nikolay Talensky, a military historian who was not Jewish, Tolstoy returned to Moscow from his trip to the Krasnodar and Stavropol regions in bad shape. Unable to report on the “horror he had encountered” right away, Tolstoy ended up writing “Brown Madness,” a long essay about the Nazi atrocities not in Krasnodar but in North Caucasus, which ran in most Soviet newspapers, including Pravda, Izvestia, and Red Star, on Aug. 5, 1943, and was printed as an “agitator’s aid” booklet.

The word “Jew” and its cognates appeared 13 times in Tolstoy’s essay. “At North Caucasus,” Tolstoy intoned, “the Germans murdered the entire Jewish population, most of it having been evacuated during the war from Leningrad, Odessa, Ukraine, Crimea.”

Some Shoah researchers, among them the Moscow-based historian Ilya Altman, consider Tolstoy’s “Brown Madness” to be the zenith of Soviet wartime openness about Jewish death in the occupied Soviet territories. At the same time, as the British cultural historian Jeremy Hicks has argued, “Tolstoy does not elaborate on the overall Nazi plan or ideology, but calls for the German people to awaken from the ‘Brown Madness’ of Nazism …” Hicks observed that in 1943 “Tolstoy’s insistence that the Nazi ideology is a kind of insane state of mind that has possessed the German nation, rather than an expression of their innate savage animality, further breaks with the wartime Soviet norm, and anticipates the ideological approach to the mind-set of the perpetrators that was to emerge at Nuremberg.”

It was in September or October 1943, while stationed in the Kuban Cossack village of Temryuk, that Selvinsky composed the poem “The Trial in Krasnodar,” two drafts of which I found among Selvinsky’s papers.

The fundamental narrative and compositional structure of the original 1943 text have survived throughout its four known rounds of revisions, while some of its salient elements changed in the spring and summer of 1945. The poem focuses on the interrogation of one of the accused, Rechkalov (in the poem spelled as “Rychkalov”), followed by the testimony of Kotov, a witness who identifies Rechkalov as one of the operators of a mobile gas van. Selvinsky’s authorial “I” sits next to Aleksey (“Alyosha”) N. Tolstoy, whose sotto voce remarks and body language indicate that he doubts Rechkalov’s culpability.

Described naturalistically, Tolstoy comes across as an unpleasant character. I will deliberately offer a very literal, and not a literary, translation, so as to underscore Selvinsky’s articulation:

Tolstoy winked and with the whole palm of his hand

sliding across his fat face, makes a clucking sound:

“Ha!

The presiding judge isn’t having a very good time.”

The poem culminates with the scene of the public hanging of the eight (called izmenniki, betrayers, in the poem):

And now a military basso at the microphone

reads the verdict. The command rumbles.

The trucks tear off

and the step stools fall over. But Rychkalov,

making an unimaginable effort,

in this shameful, in this kulak’s thirst to live,

managed to climb the side of the vehicle,

and lived a second longer than the others.

And in the air, like at a country fair on Easter,

some sort of a family of ropewalkers,

their chins cutting into the ropes,

jumped, seized, danced,

threaded, fluttered, thrusted

into the sky like a nauseating swing

in an unthinkable flight and span

all at different speeds and directions,

to the thunder of insulting ovations,

like sports champions, straining themselves

and making rabid records.

Then they started moving calmly and evenly,

like pendulums, slow and steady,

as if relaxing after a match,

still calmer, calmer and now very calm,

and finally reaching the point of sleep,

as if coming to a complete stop,

suddenly they rotated very busily

around their axes, some to the right others to the left.

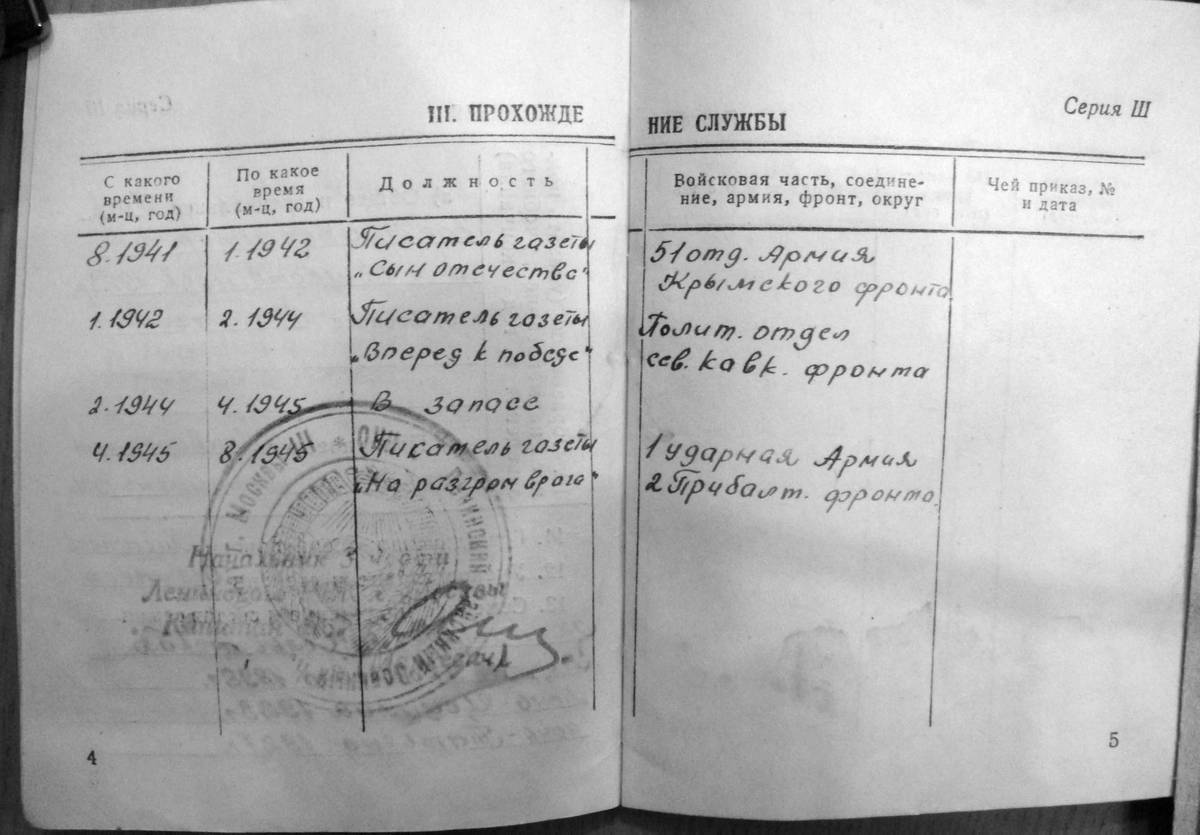

The poet agonized over the execution scene, as evident from the surviving versions. Note the crossed-out line “to the thunder of insulting ovations,” which likely speaks to the ugliness of the Soviet public performance of the execution.

Selvinsky ended the poem with an argument, in which Tolstoy wants Selvinsky to join him in feeling sorry for “them”—the hanged collaborators. The argument has its deep roots in Selvinsky’s earlier experience as a poetic witness to the Shoah in his native Crimea:

“Do you feel sorry for them?” Tolstoy asked me.

“Not really. I’m just curious.”

“You lie.”

“And you, Alyosha, have you seen in Kerch

seven thousand corpses?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“Seven.

There were children, women, handicapped.

It’s possible THESE very ones shot them.

One, I remember, was an old woman. And one

just like the Madonna with the child Jesus.

Now for them I felt sorry.”

“Hmm… I see.

Besides as a military officer you must

develop a certain sternness

or in the very least a habit.

My dear, I understand you very well.

I very much… Which way are you going?”

“Straight.”

“Be well.”

“Good night.”

We do not know whether Selvinsky sought to publish the poem. But less than two months after the composition of “The Trial in Krasnodar,” Selvinsky was summoned and flown to Moscow from eastern Crimea, chastised at a meeting of the Orgburo of the Central Committee (at which Stalin made a theatrical appearance), and made persona non grata of Soviet culture. In the autumn and winter of 1943-1944, the Jewish-Russian poet Selvinsky would become the target of three party resolutions, including one singularly vilifying his wartime poetry—apparently the only such wartime resolution.

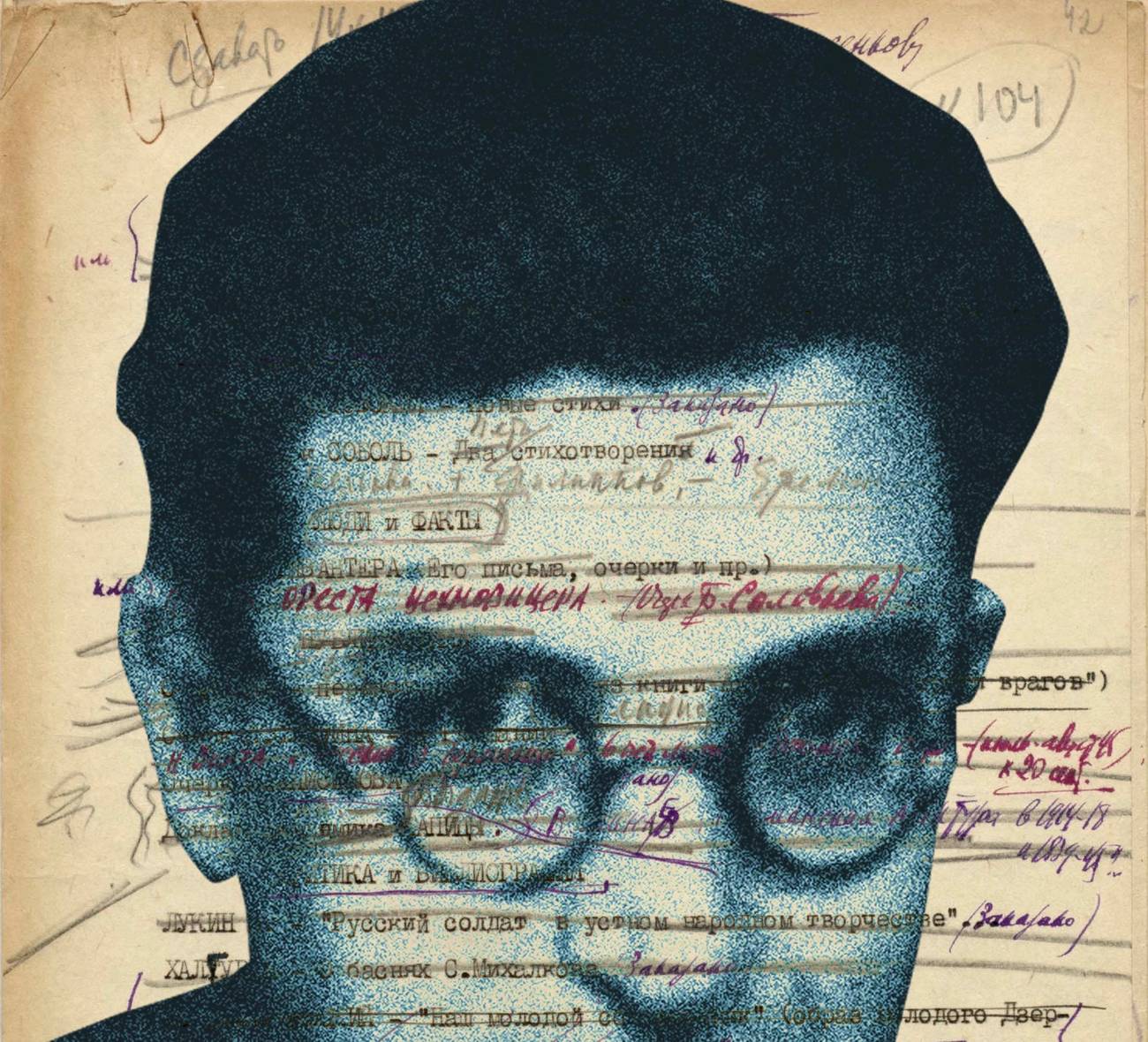

Ilya Selvinsky’s military papers; the period of punitive demobilization is euphemistically referred to as being a ‘reservist’Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

Behind Selvinsky’s troubles with Stalin’s leadership were his poems of bearing witness to the annihilation of Jews in the occupied Soviet territory. He would be punitively discharged from the military and blacklisted, and spent over a year in de facto exile in Moscow, away from the front and what he saw as his duty as a Jew, a Russian, and a Soviet. By the late spring of 1945, when Lieutenant Colonel Selvinsky was finally rehabilitated and permitted to return to the army (in his military papers the period is euphemistically referred to as “reservist”), a number of factors central to our story had changed.

To begin with, following a major shakeup in the leadership of Soviet “thick” journals in late 1943 and early 1944, Vsevolod Vishnevsky (1900-1951) was reappointed as editor of the distinguished Moscow monthly Znamia (Banner). The playwright and literary functionary Vishnevsky, son of a noble family from St. Petersburg decorated for valor in Word War 1, had been a machine-gunner and political officer during the Civil War. Author of the famous Optimistic Tragedy, arguably the only officially billed Soviet “tragedy,” a consummate letter writer and telephonophobiac, Vishnevsky spent two and a half years in and around the besieged Leningrad, heading a writer’s group attached to the Baltic fleet.

An orthodox Communist in matters of stated ideological beliefs, a man whose unrealized ambition and—in the words of longtime editor Boris Zaks who worked with Vishnevsky at Banner—“obsession [was] to become part of Stalin’s inner circle,” Vishnevsky was undogmatic in matters of artistic form. In 1944-1946, under Vishnevsky’s editorship, Banner became the most important Soviet mainstream venue for the publication of Shoah-related materials in the Russian language, among them poetry by Ilya Selvinsky and Pavel Antokolsky and nonfiction by Vasily Grossman. Shoah publications that Vishnevsky featured in Banner included sections of the (yet-to-be-derailed) Black Book, most notably Pavel Antokolsky and Veniamin Kaverin’s “The Uprising at Sobibor” and Grossman’s The Hell of Treblinka. Of the writers appointed by Stalin’s leadership to Banner’s editorial board, the most influential was Konstantin Simonov (1915-1979), poet, playwright and novelist of Russian and Armenian origin, son of a czarist general and a Russian princess. While sensitive to Jewish suffering, Simonov was even more attuned to the direction of the smoke from Stalin’s pipe. (The height of Simonov’s engagement with the Shoah would come in August 1944, when he was assigned to cover the liberation of Majdanek.)

Vsevolod Vishnevsky, left, with fellow naval and infantry officers, Baltic fleet, early 1944. Note Vishnevsky’s displayed World War I decorations below Soviet decorations.Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

The second contributing factor had to do with the perceived impact of public hangings at the July 1943 Krasnodar Trial and the December 1943 Kharkov Trial (where three Nazi officers and a collaborator were sentenced to death and hanged). These spectacles had stirred up something of a debate that had initially involved authors and journalists who were present at these trials. Soviet literary brethren argued not only about public hangings but about capital punishment as such, invoking views that hearkened back to the beginning of the 19th century. Their positions were intricate, ambivalent and inconsistent, going beyond the expected boundaries of ideology, ethnic (and what had remained of religious) identity, cultural pedigree, and aesthetic predilections.

In his memoir People, Years, Life, Ehrenburg included a cryptic comment about the execution of the convicted four after the Kharkov Trial: “I did not go to the square, where the convicted ones were to be hanged. Tolstoy said that he had to be present, would not dare excuse himself. He returned from the execution darker than a storm cloud. He was silent for a while, then started talking. What did he say? Well, the kinds of things a writer can say, the very things that prior to him had been said by Turgenev, and Hugo, and the Russian poet K[onstantin] Sluchevsky.”

Other journalists and authors present at the Kharkov Trial, among them the American journalist Edmund Stevens, registered the disputatious context surrounding the execution of Nazi criminals and collaborators, linking it simultaneously to the question of Germany’s—German—culpability and to the question of Soviet vengeance. Consider the testimony of David Zaslavsky, a Jew by birth and an odious journalist who had attacked Osip Mandelstam in 1929 and who in 1958 would defame Boris Pasternak. Zaslavsky was at the Kharkov Trial as a writer for Literatura i iskusstvo (Literature and Art), the wartime organ of the Union of Soviet Writers. In 2006 excerpts from Zaslavsky’s journal were published by the historian Nikolay Pobol, furnished with a provocative commentary by the scholar of Jewish-Russian literature Leonid Katsis.

Loathe as I am to quote Zaslavsky, his observations, composed with a combination of candor and political reptility, capture the whiff of time.

Aleksey N. Tolstoy, Konstantin Simonov, Ilya Ehrenburg; Kharkov, December 1943Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

On Dec. 10, 1943 Zaslavsky describes socializing with other journalists and reporters: “Awaiting the [Kharkov] trial. Yesterday I spent time with Ehrenburg, Aleksey Tolstoy and Simonov—like being in a menagerie. … Ehrenburg talked … about the need to eradicate all Fritzes ages 16 to 35. Tolstoy said that all Fritzes should be eradicated, as a harmful race. We listened, without objecting, the way one listens to amusing children. … I regret not having voiced my objection to Ehrenburg in a different way … Why not till 60 years? … Ehrenburg said that he did not care for the hanging, that it corrupts people; he prefers that there be ten executed by shooting for each hanged one. Elena [Pravda reporter Elena Kononenko] said that in Krasnodar the hanging gave her a personal moral satisfaction, as it had thousands of old and young people. She was only concerned about the attitude of children to the hanging as a curious spectacle. I let it drop that hanging is a people’s form of vengeance conjoined with contempt. Hanging is a shameful way of death. Contained in the public hanging is its own important meaning for our time.”

Ehrenburg, a Russian Jew, a friend of Picasso’s and a civilian to boot, had witnessed the fall of Paris and in 1941 became the principal architect of the “Kill the German” Soviet rhetoric. Did the same Ehrenburg privately question public hangings as spectacles of the people’s vengeance? To run ahead of ourselves, let us recall that on April 14, 1945, as the Soviet troops prepared to storm Berlin and the British troops were about to liberate Bergen-Belsen, an article against Ehrenburg’s position on the German question would be published in Pravda. Titled “Comrade Ehrenburg Simplifies,” the article was penned by the same party boss Georgy Aleksandrov who had overseen the Krasnodar Trial and drafted the 1943-1944 party resolutions against Selvinsky and Soviet literary magazines. “Comrade Ehrenburg assures the readers,” Aleksandrov wrote, “that all the Germans are alike and that they will all to the same measure be responsible for the crimes of the Hitlerites.”

Ehrenburg’s status notwithstanding, the Pravda article would bear naked a new reality, in which a Jew could no longer teach the Soviet—Russian—people about vengeance. The party would take back the reigns of the national discussion about the terms and forms of assigning culpability and administering justice. But as far as the years 1943-1944 are concerned, the voyeuristic spectacles of the capital punishment of Nazis, their allies and their accomplices caused a skeptical reaction among some Soviet writers and intellectuals.

Finally and very importantly for the polemic and the fate of Selvinsky’s report-in-verse on the Krasnodar Trial, Aleksey N. Tolstoy had died of lung cancer in February 1945 and was given a state funeral. The death of Tolstoy untied Selvinsky’s hands as he contemplated the (re?)submission of “The Trial in Krasnodar.” In the early spring of 1945, prior to his reinstatement and departure for the 2nd Baltic Front, Selvinsky tested the waters by offering his poem “Kerch” to Vishnevsky and his co-editors, who quickly published it in Banner. In “Kerch,” all four of the witnesses documenting the aftermath of the murder of Jews in Crimea—a prose writer, a photographer, a literary critic and a poet (Selvinsky himself) are marked as Jews while the victims’ Jewish identity is not plainly stated.

Ilya Selvinsky, left, Yakov Khelemsky, center, with fellow servicemen, Kurland, May 1945Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

In the victorious spring of 1945, the very air of culture was heady with vengeance against Germany and Germans.

Selvinsky was placed in charge of a group of military journalists and dispatched, via Klaipeda, across East Prussia to Königsberg. The Jewish-Russian poet Yakov Khelemsky, who wrote about the destruction of Jewish life in Latvia, accompanied Selvinsky on the trip. He recalled a telling episode. Selvinsky helped the family of an injured German girl, thus causing the ire of another frontline reporter, his junior in rank and an ethnic Slav: “Wasn’t it a bit much, Comrade Lieutenant Colonel … What did they do with our children!” Turning livid, Selvinsky replied: “Comrade Captain, you forget that we’re liberating from fascism not only our land, but Germany. … The ditch outside Kerch still haunts me in my dreams. So does this mean that I should respond to it with a Königsberg ditch?”

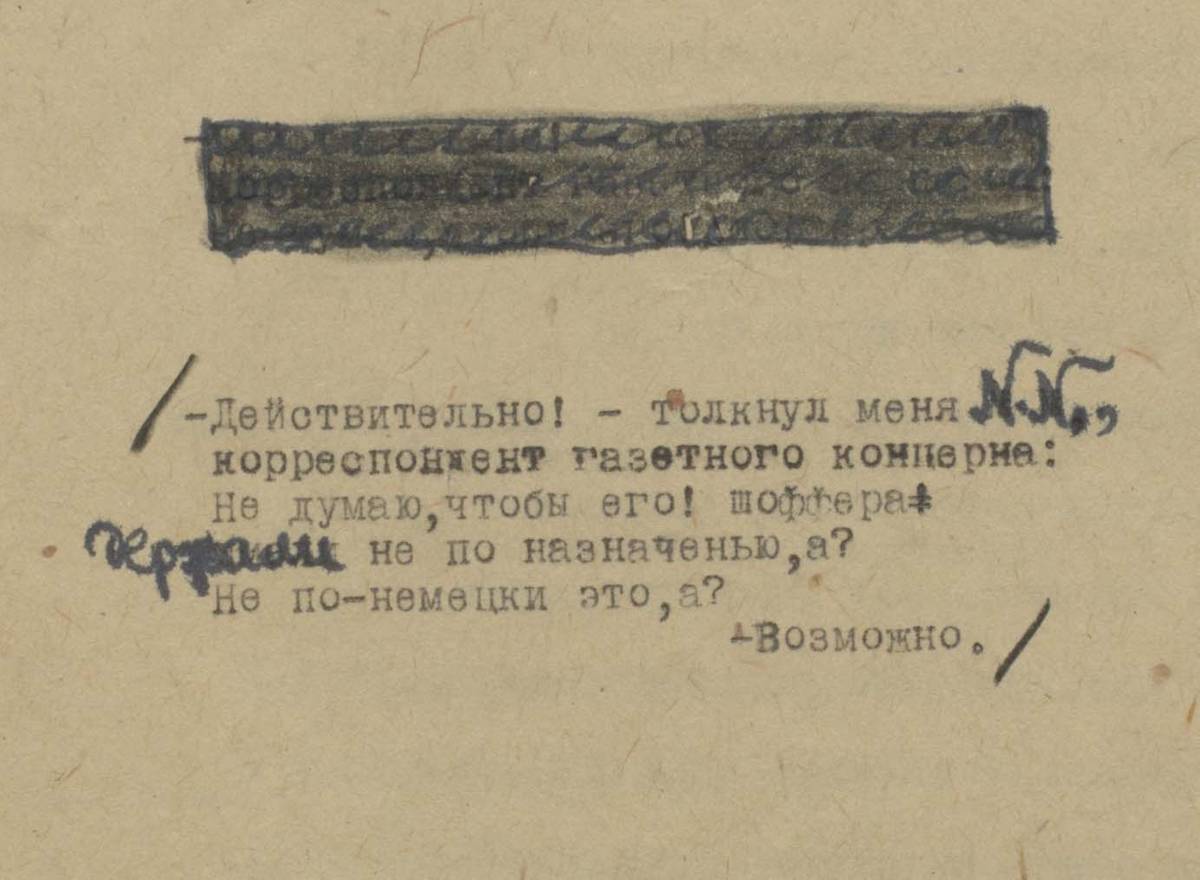

Page 10 of the third draft of Ilya Selvinsky’s ‘Trial in Krasnodar’ with major changes. Aleksey N. Tolstoy becomes N.N., a foreign journalist.‘Banner’ magazine editorial papers at the Russian Archive of Literature and the Arts in Moscow, courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

Selvinsky returned to Moscow from the Baltics in the summer of 1945 and submitted a revised text of “The Trial in Krasnodar” to Banner. From the original text composed in 1943, Selvinsky had retained a variant of the execution scene and a discordant ending, to which, judging by the copy which I have discovered in Banner’s editorial trove at the Russian Archive for Literature and the Arts, he added important dimensions. I quote from the execution scene:

The military trumpet sings attention,

At the microphone in hot silence

the verdict is read. Five notes of the command.

The drum has shuddered in a near-death shiver.

[ … here Rechkalov’s hanging is described]

And then

one seventh of the crowd (yes, yes one seventh)

in wordlessness ominously erupted

with a frozen fury of ovations.

And then again not a sound. It was terrifying.

And sacred. And again, again a ballad.

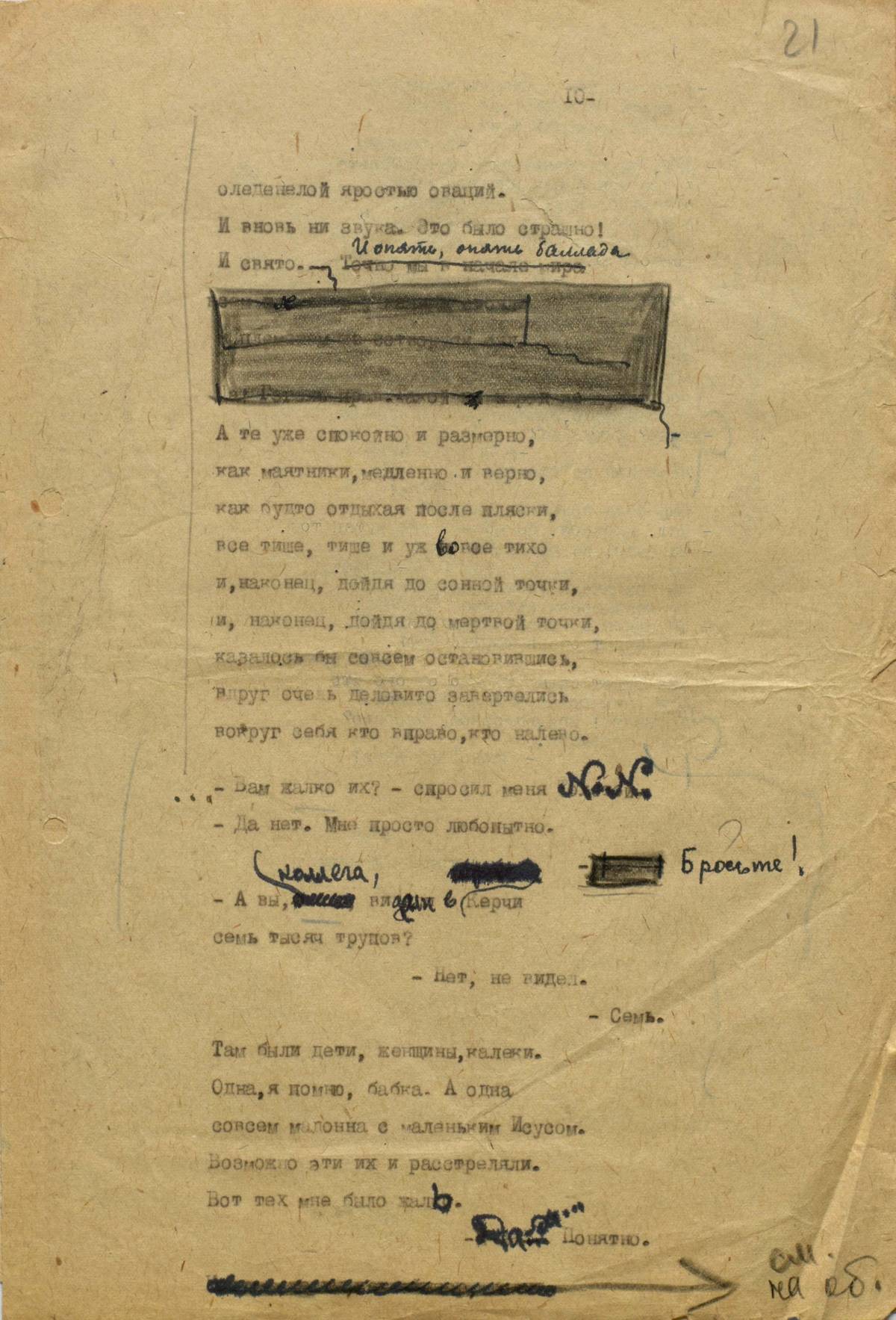

On Sept. 25, 1945 three members of Banner’s editorial board submitted internal readers’ reports on the poem.

They included Konstantin Simonov (Stalin’s favorite whom we already met); critic Anatoly Tarasenkov, something of an evil genius of Soviet poetic history who as an editor worked with Boris Pasternak and who, during the anti-Cosmopolitan campaign, would famously lash out at Selvinsky and another major Jewish-Russian poet, Eduard Bagritsky, charging them with “bourgeois nationalism”; and Nikolai Tikhonov, a major early Soviet poet who sold out and largely wasted his talent. All three asked that the execution scene be cut. Tarasenkov’s report was quite enthusiastic: “An interesting, powerful poem, converging in style and mood with those works by Selvinsky that we published in the winter. I speak in favor of publishing this text in No. 11 of Banner. However, … the scene of the hanging of traitors strikes me as unsuccessful (somehow morbidly naturalistic).” Simonov’s report is the most articulate in its resolve to remove the execution scene: “The poem is good and powerful, except, of course, we should not even consider keeping the scene of the hanging. It is not in the traditions of Russian literature to describe this and it is not in the traditions of Russian journalism to print this. … I think that we should ask [Selvinsky] to drop everything that lies between the lines ‘The drum has shuddered with a near-death shiver’ and the line ‘Do you feel sorry for them? Tolstoy asked me.’ This can be thrown out absolutely painlessly, and the poem, even in purely aesthetic terms, becomes at least twenty-five times better.”

Simonov’s report, which he would wait to air in public until 1971, is fascinating for many reasons, including its disregard of a number of foundational texts of classical Russian literature, early 20th-century literature, and Soviet literature, or its conflation of the Russian historical debates about capital punishment as such and public execution versus execution carried out in closed execution chambers. A short list of 19th-century works depicting capital punishment would include narrative poetry and prose by Aleksandr Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolay Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Inserted revised section of the opening section of Selvinsky’s ‘The Trial in Krasnodar’‘Banner’ magazine editorial papers at the Russian Archive of Literature and the Arts in Moscow, courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

A close examination of the next round of revisions, found in the editorial archive of Banner, shows that Selvinsky was prepared to forgo the depiction of Aleksey N. Tolstoy (even though he was not explicitly pressured to do so), but fought tooth and nail to keep at least some version of the hanging.

In obliterating Tolstoy, Selvinsky replaced him with N.N, a Western journalist:

“Indeed,” elbowing me, said N.N.,

a reporter for a newspaper corporation.

“I don’t believe that he, a driver,

was used not according to his job description, yes?

This isn’t the German way, yes?”

“Perhaps.”

The foreign correspondent who appears in “The Trial at Krasnodar” later states that Selvinsky’s ruthless comments about the collaborators were driven by propaganda. Contextual evidence links N.N. with the British journalist Alexander Werth, born in St. Petersburg to English parents. A BBC correspondent in the USSR in 1941-1946, Werth contributed the program “Russia Commentary,” which gathered about 12 million listeners, and reported on the 1943 Krasnodar Trial. In his book Russia at War, Werth would speak of the trial as mainly a performance of Soviet propaganda.

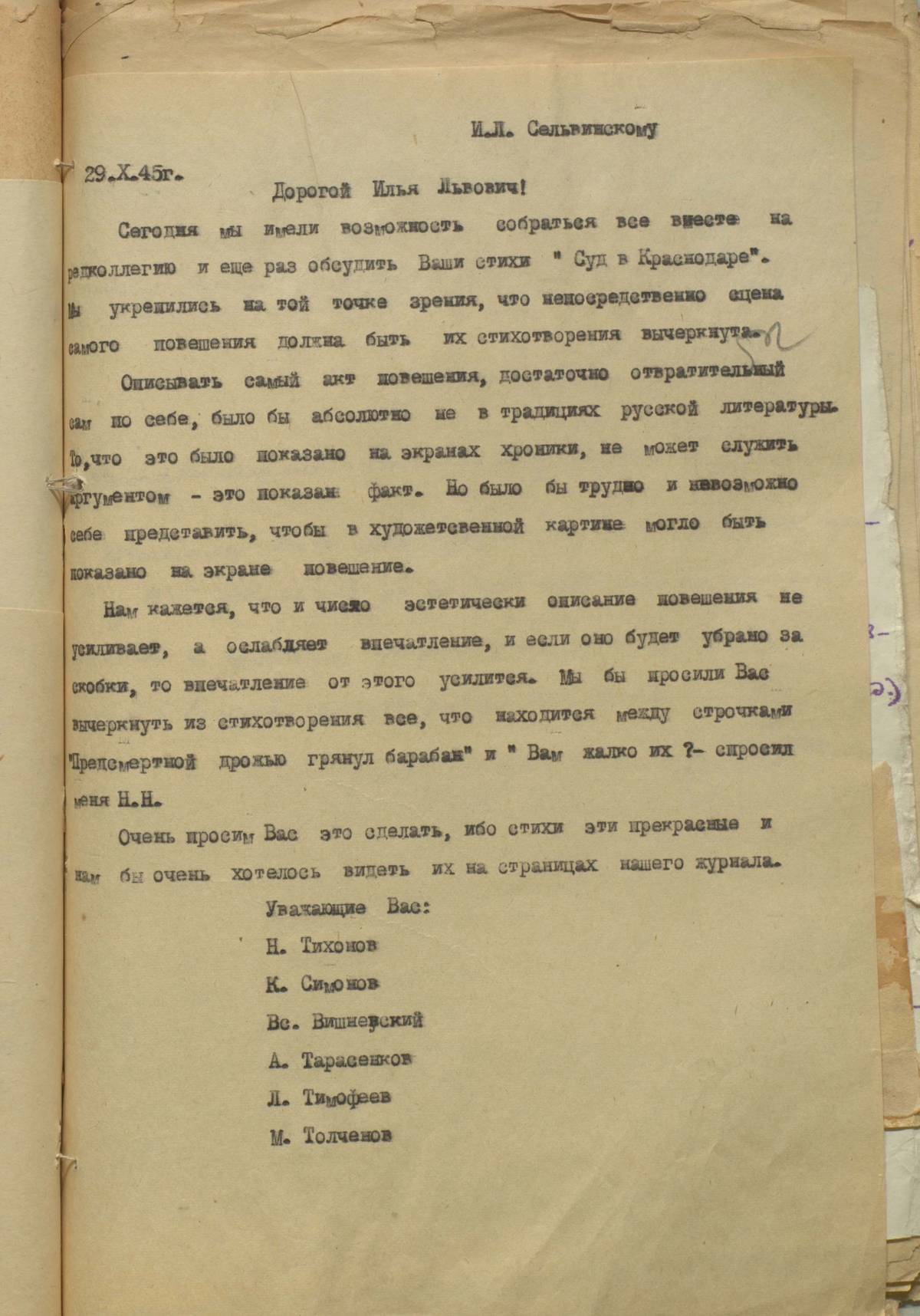

On Oct. 29, 1945, the entire editorial board of Banner sent a letter to Selvinsky, pleading with him to remove what was left of the description of the public hanging:

Letter by members of ‘Banner’ editorial board to Ilya Selvinsky, Oct. 29, 1945, signed: N. Tikhonov, K. Simonov, Vs. Vishnevsky, A. Tarasenkov, L. Timofeev, N. Tolchenov‘Banner’ magazine editorial papers at the Russian Archive of Literature and the Arts in Moscow, courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

Today all of us had the opportunity to meet as the editorial board and to discuss, one more time, your poem ‘The Trial in Krasnodar.’ And we became further convinced that the actual scene of the hanging itself must be crossed out from the poem.

To describe the very act of hanging, rather repulsive in itself, would be absolutely outside the traditions of Russian literature. The fact that this was shown on screen in a newsreel must not serve as an argument—it was the fact that was being shown. But it would be difficult and impossible to imagine that a fiction film would show a hanging on screen. …

… We would ask you to cross out from the poem everything between the lines ‘The drum has shuddered with a near-death shiver’ and the line ‘Do you feel sorry for them? N.N. asked me.’

We would be most grateful if you could do it as it is a splendid poem and we would very much like to see it on the pages of our magazine.

N. Tikhonov,

K. Simonov

Vs. Vishnevsky

An. Tarasenkov

L. Timofeev

M. Tolchenov.

Selvinsky appears to have acquiesced and cut the hanging scene, only leaving these lines:

The military trumpet sings attention,

At the microphone in hot silence

The verdict is read. The command rumbles.

Trucks tear off—

And the step stools fall over.

Yet it would not have been within his character to have succumbed to editorial pressure without attempting to deploy further polemical gestures. In the last surviving typescript of the poem, Selvinsky dropped the reference to “the Madonna with the child Christ,” which pointed contextually to the Jewish woman (zamuchennaia evreika) with a baby massacred outside Kerch, previously described in his nationally famous poem “I Saw It.” Yet Selvinsky kept the reference to the “corpses in Kerch”:

“Do you feel sorry for them?” N.N. asked me.

“Not really. I’m just curious.”

“Stop it.”

“And you, colleague, have you seen in Kerch

seven thousand corpses?

There were children, women, handicapped.

It’s possible THESE very ones shot them.

Now for those I felt sorry. …

“Yes… I see.”

We were both silent. ‘Their correspondent’

out of politeness piously sighed:

“You’ve seen too much, colleague.

You will have a very hard time living.”

“You’re right.

I will have a very hard time because

You haven’t seen anything, colleague.

Farewell. You must be turning right?”

“Be well.”

“Good night.”

The ending recalled Selvinsky’s deep troubles with Stalin’s regime in 1943-1944, when he indeed had a “hard time” surviving as a Jew and a Soviet writer, and anticipated his further troubles in 1946-1950.

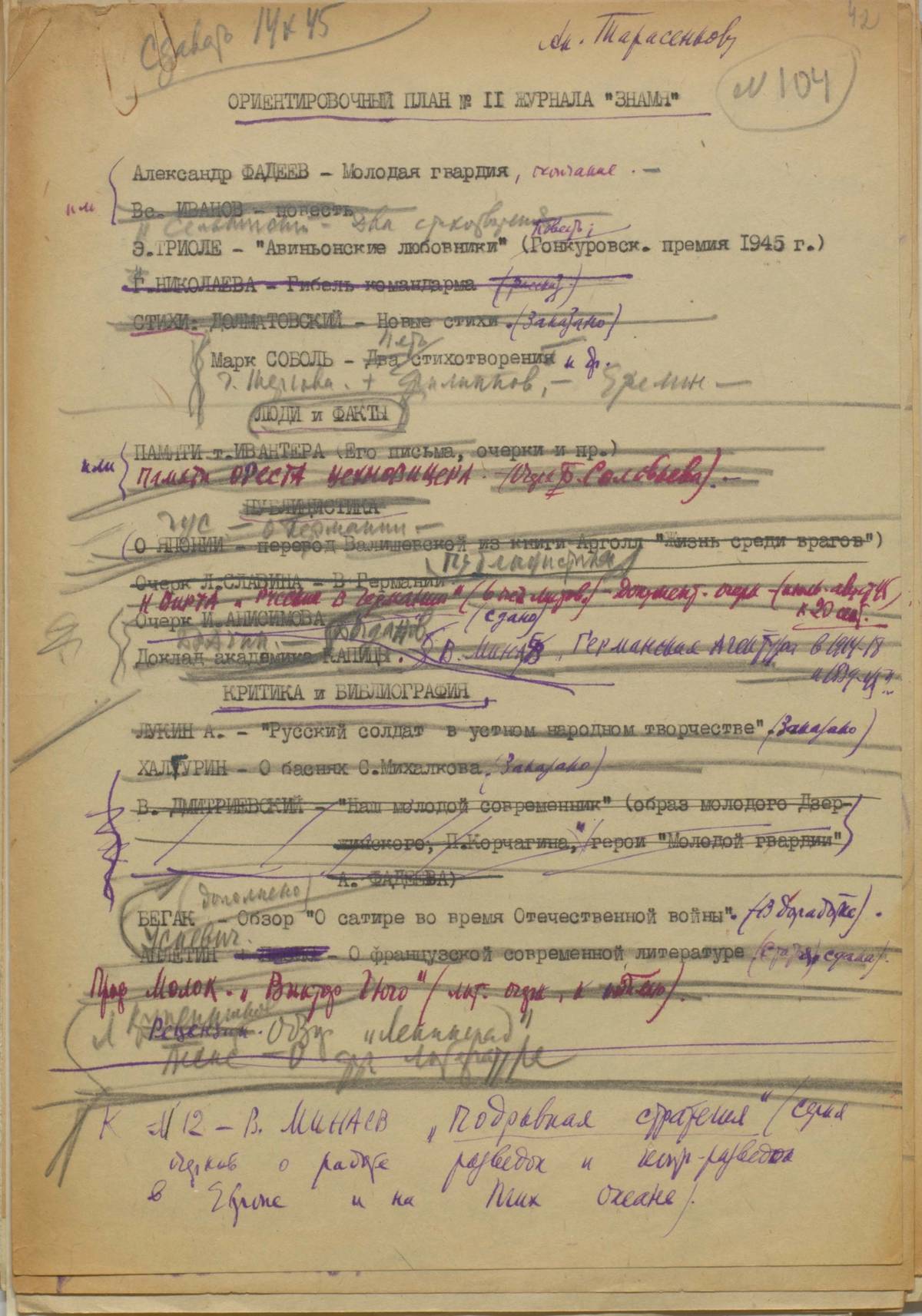

The poem was slated to appear in the November 1945 issue of Banner, in the same issue with an installment of the original version of Aleksandr Fadeev’s novel Young Guard and the authorized translation of Elsa Triolet’s tale The Lovers of Avignon.

Draft of the contents of issue 11 of ‘Banner’ for 1945 with two poems by Selvinsky added in pencil (line 3) below Aleksandr Fadeev’s ‘Young Guard’ and above Elsa Triolet’s ‘The Lovers of Avignon’‘Banner’ magazine editorial papers at the Russian Archive of Literature and the Arts in Moscow, courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

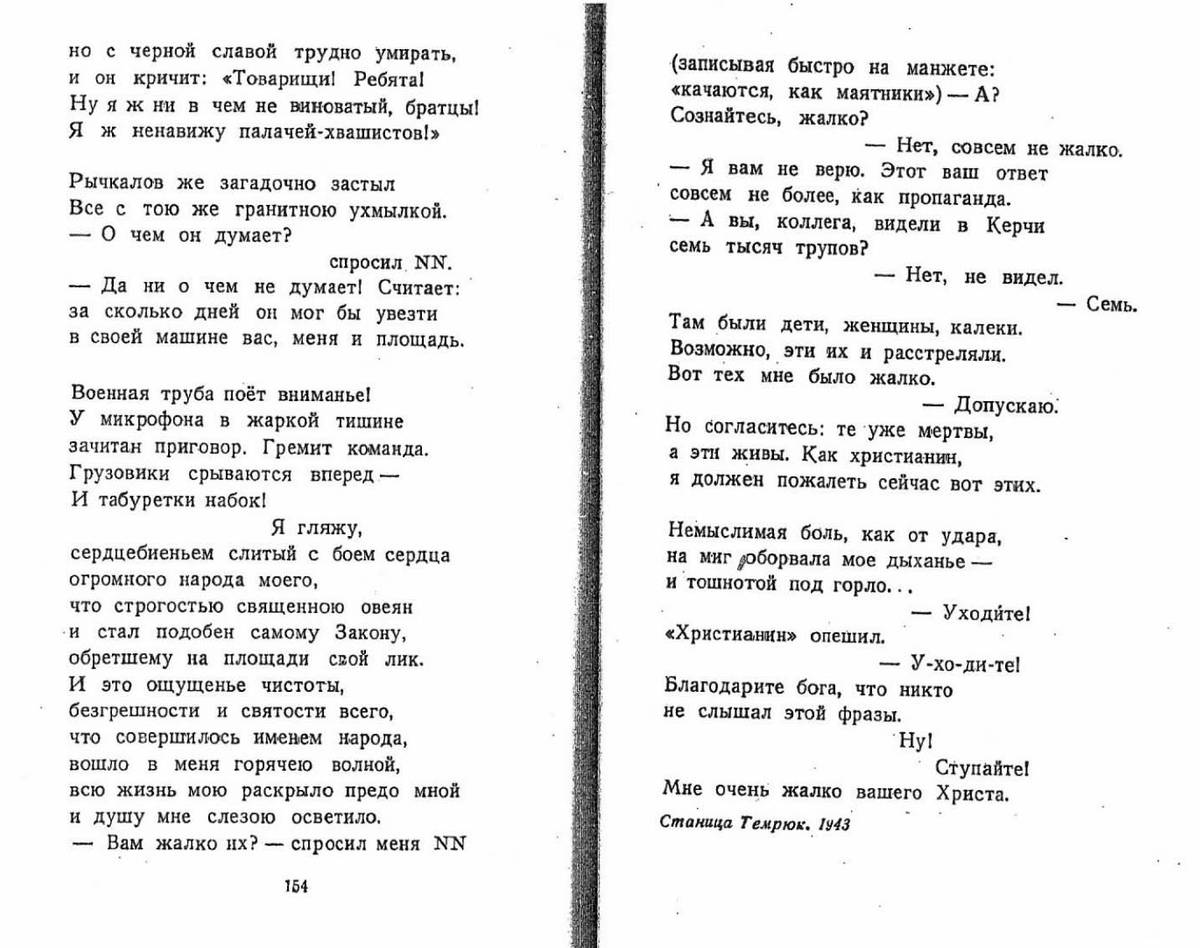

When “The Trial at Krasnodar” was published alongside Selvinsky’s elegantly versified poem “Swan Lake” about the survival of classical beauty amid ruins of the war, however, the ending was different than in the clean copy prepared for publication. Selvinsky most likely made the changes in the galleys, and we do not know the extent of last-minute editorial—or shall we say censorial—involvement:

“Do you feel sorry for them?” N.N. asked me

(writing down on his shirt cuff:

“swinging like pendulums”). “Well?

Admit, you do feel sorry?”

“No, I don’t feel sorry at all.”

“I don’t believe you. This answer of yours

is no more than propaganda.”

“And you, colleague, have you seen in Kerch

Seven thousand corpses?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“Seven.

There were children, women, handicapped.

It’s possible THESE ones shot them.

Now for them I felt sorry.”

“I can imagine.

Yet don’t you agree: Those ones are already dead,

But these are alive. As a Christian

I must now feel sorry for these ones.”

An unthinkable pain, as if from being struck,

Cut my breath short for a moment

And [hit] with nausea at my throat.

“Go away.”

The “Christian” was astounded.

“Go-a-wa-ay!

Thank god that nobody

heard your last phrase. Your hotel,

the second block and on the right. Go now!

I feel very sorry for your Christ.”

Last page of Ilya Selvinsky’s ‘The Trial in Krasnodar’ as printed in his collection ‘Crimea Caucasus Kuban’ (Moscow, 1947) Courtesy of Maxim D. Shrayer

Perhaps paradoxically, and certainly at the expense of depicting the execution of Nazi collaborators, in the published version Selvinsky underscored a Jewish perspective. He prevailed in referencing the 1941 massacre outside Kerch while also showing that the foreign correspondent N.N. (who serves as a stand-in for the Russian writer Aleksey N. Tolstoy) calls himself a “Christian” (note the quotation marks) yet calls for mercy toward the murderers of Jews in the name of the Jew Jesus. If the published ending feels strained or even tortured, this has a lot to do with Selvinsky’s desire to compensate for being unable, in keeping with the proceedings and coverage of the 1943 Krasnodar Trial, to state plainly that the collaborators had participated in the annihilation of the Jewish population—had perpetrated what we now call the Shoah.

As an epilogue to this story, consider the point and counterpoint of the following facts. The first is that in 1945-1947 a wave of Soviet trials of Nazi and allied criminals followed in the footsteps of the Krasnodar and Kharkov trials, including the Kiev, Leningrad, Minsk, Riga, and Smolensk trials, and each trial ended with a staged public hanging that was filmed and reported. In late 1947 the open public trials were replaced with military tribunals without open proceedings or capital punishment. The second is that in 1948 Vsevolod Vishnevsky, who featured two of Ilya Selvinsky’s four most significant Shoah poems and other key Shoah texts in his magazine, was removed from his post as editor of Banner, in part because he continued to publish Jewish writers as the anti-Cosmopolitan campaign gained speed. Vishnevsky was replaced by a predictable Russian loyalist. The third is that after the 1945 Banner publication, Selvinsky’s “The Trial in Krasnodar” appeared virtually unchanged in his large collection of wartime poetry Crimea Caucasus Kuban (1947). After that, for reasons we have yet to understand completely, Selvinsky’s “The Trial in Krasnodar” has not been reprinted, either during the Soviet period or at any time during the post-Soviet years.

The Krasnodar Trial cast a long shadow over subsequent trials of Nazis and Nazi accomplices in the USSR and over the international and national tribunals of postwar and post-Shoah justice, not just in the aftermath of the war but well into the 1970s. As I was putting the finishing touches on this essay, I turned to my colleague Devin Pendas, Boston College professor, historian of postwar Nazi trials and author of Democracy, Nazi Trials, and Transitional Justice in Germany, 1945-1950. When I asked Pendas to assess the historical importance of the Krasnodar Trial, he answered this way:

While the Western Allies worried that Soviet trials for Nazi crimes during the war might prompt retaliation against Allied POWs, the Krasnodar Trial helped convince the Americans and the British that some kind of policy on postwar trials needed to be formulated sooner rather than later. One result was the so-called Moscow Declaration issued in October 1943, a few months after the end of the Krasnodar Trial [and just two weeks before the opening of the Kharkov Trial]. In this, the Big Three Allies promised a postwar legal reckoning with Nazi crimes, in local courts for lesser offenses, but by a procedure to be decided jointly by the Allies for the leadership whose crimes transcended local or national boundaries. This was the first step on the path toward creating what became the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. That court in turn set the pattern for using international as well as domestic law to punish Nazi criminals, a global project that is only now winding down as the few remaining perpetrators die of old age. Krasnodar was the first Nazi trial; it was hardly the last.

Nor, may I add, was it the last trial of Nazis and Nazi collaborators on which prominent Soviet writers and filmmakers, both Jewish and not, reported from the courtroom while desperately trying to negotiate among matters of official doctrine, artistic predilection, and national commitment.

Why revisit the story of how the first Nazi trial was reported by a poet in uniform? I believe the story of Ilya Selvinsky—poet, military journalist, Soviet Jew struggling to paint a full picture of the Krasnodar Trial—resonates with special significance today, when questions of historical erasure and control of a national historical narrative are tearing apart the fabric of daily life both in America and in Russia. A writer, especially a writer of nonfiction, would probably identify with the plight of a colleague navigating the treacherous straits of censorship. But my inner Russian immigrant, a descendant of shtetl screamers, recalls a salty Jewish joke—an “anecdote” in the Soviet sense—that our Yiddish-speaking great-grandparents and grandparents used to tell in the postwar Soviet years. The joke had originally referred to real personages, but the past 70 years have transcended the joke’s context, making its protagonists into historical symbols.

There are three Jews left in Russia, so goes the joke, the shrayber (“one who writes”), the shrayer (“one who screams”), and the shvayger (“one who keeps silent”). All of them have since emigrated from Russia. What’s left are the drafts of a strangled poem.