‘Lashon Hara’: Available Now on a Phone Near You

A new app called Secret lets users share gossip anonymously. It’s a very bad idea.

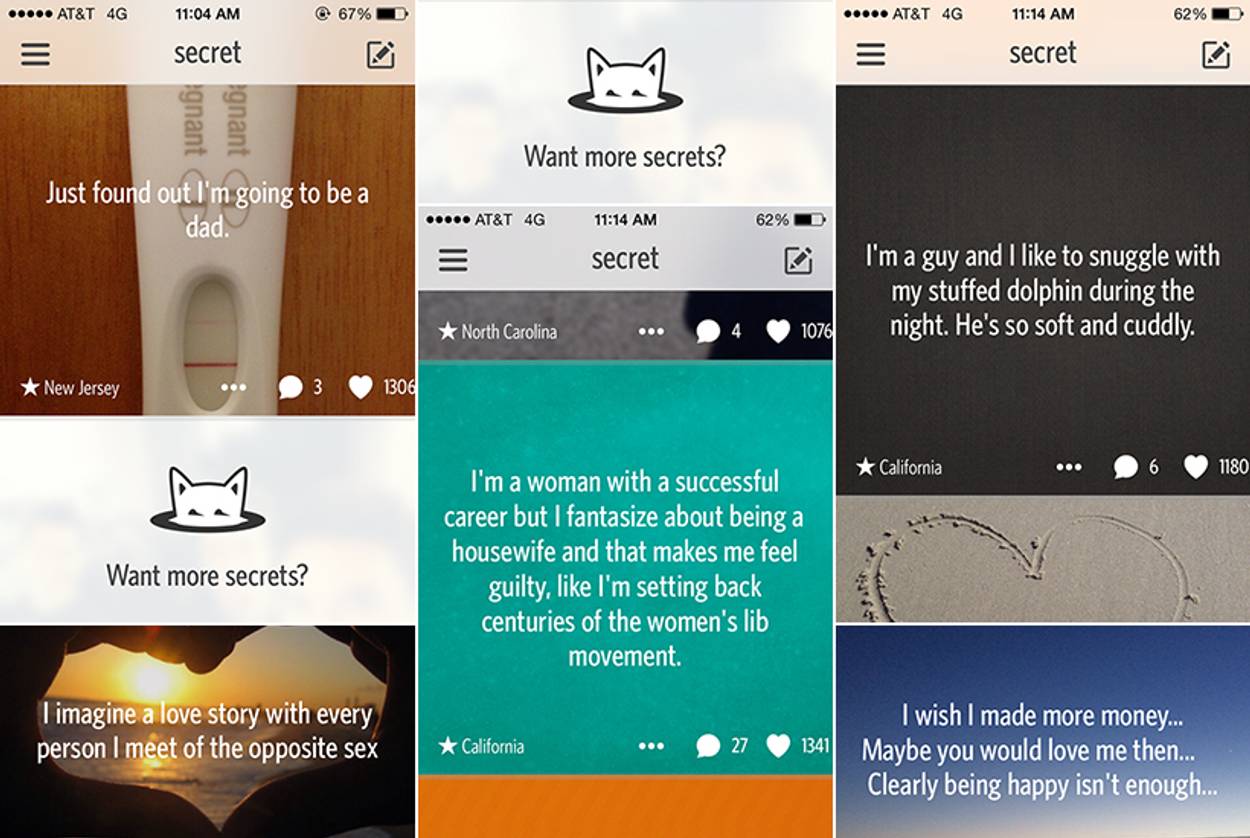

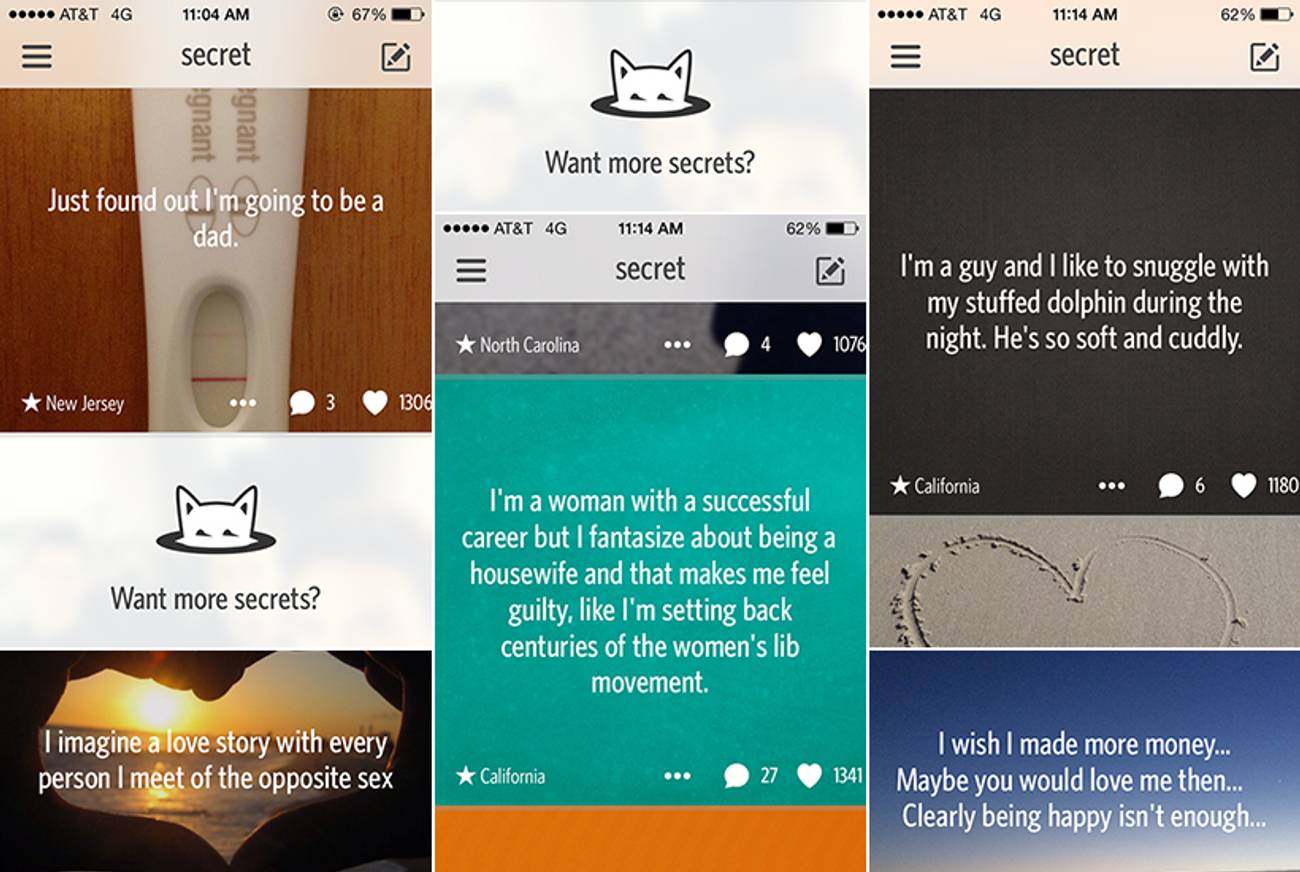

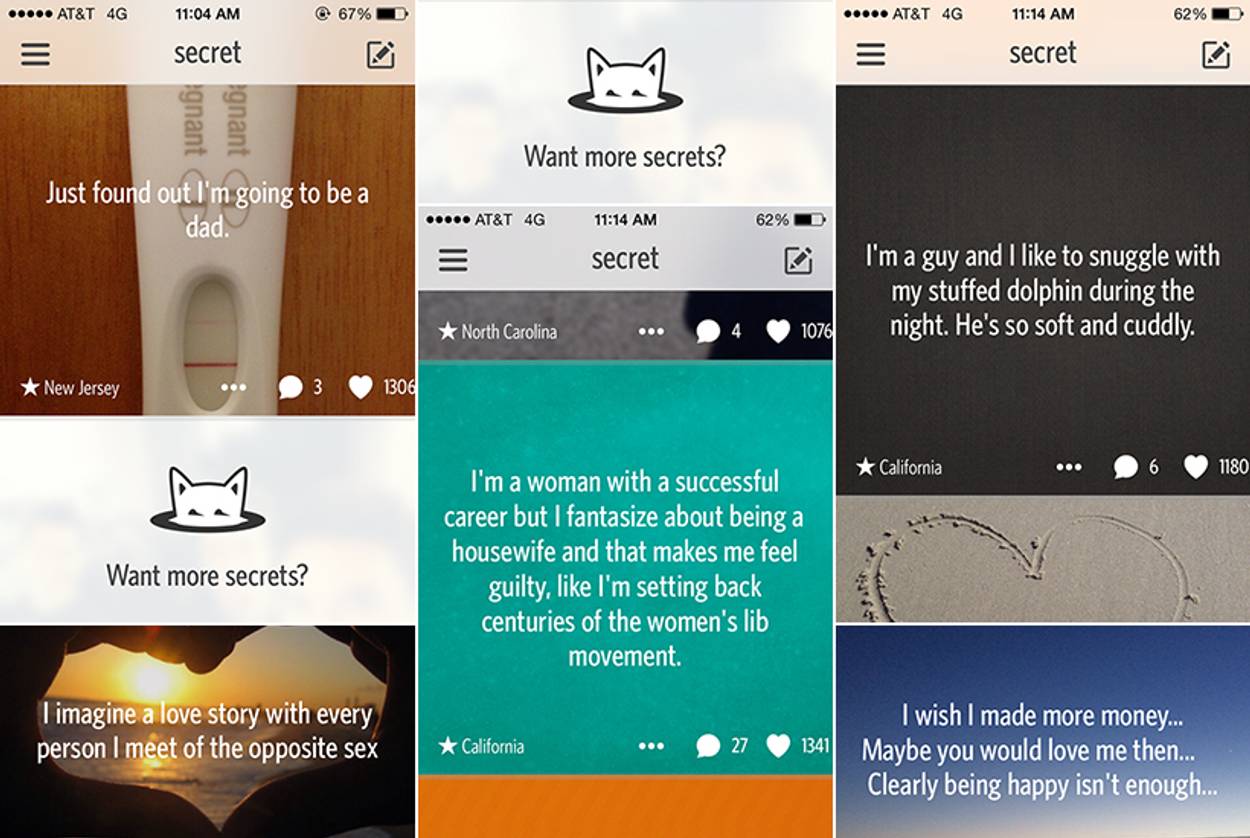

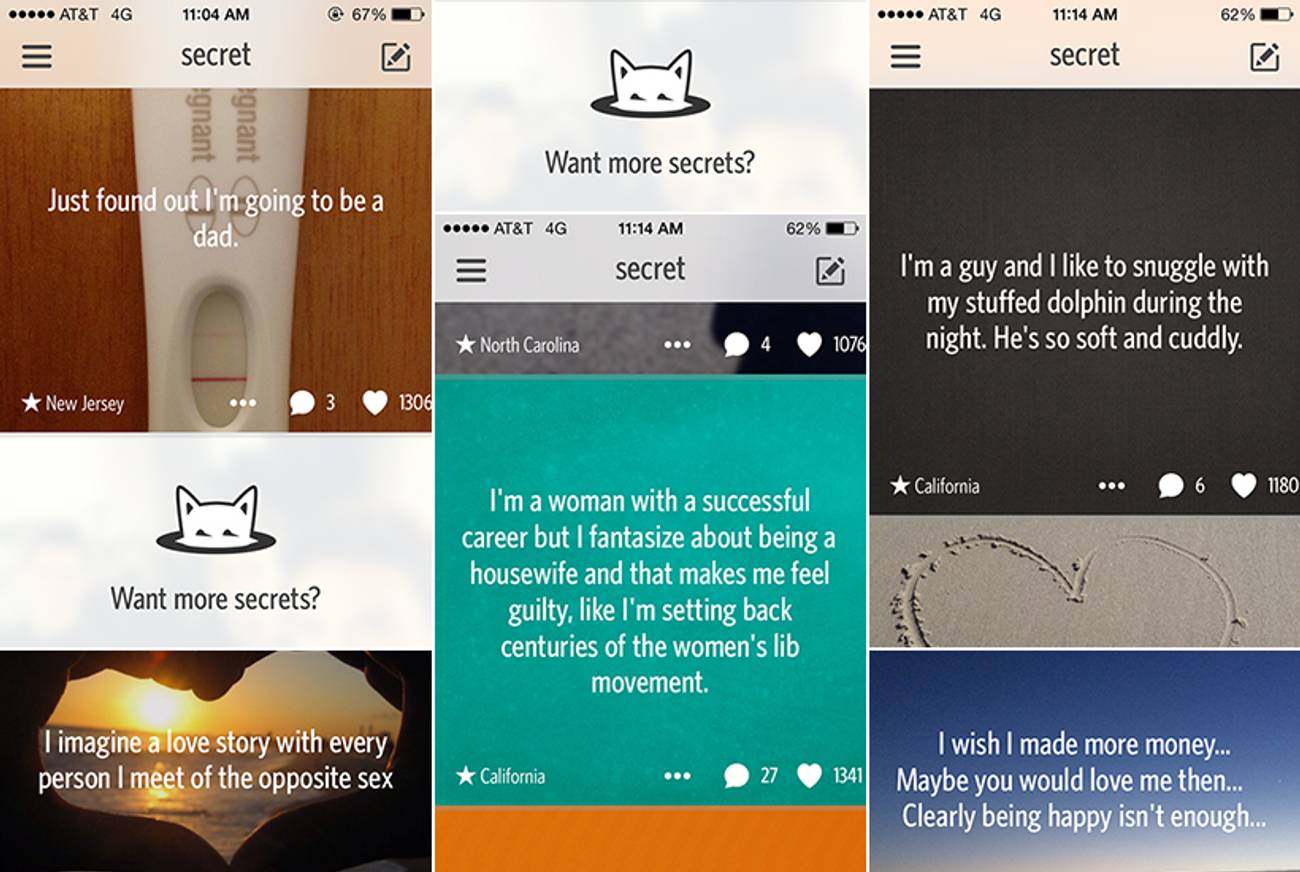

This week, I learned that someone I knew had been unfaithful to her long-term boyfriend. Another was still hung up on a relationship he’d ended six years earlier. And a third had relieved himself inside a can of Pringles before handing it to an unsuspecting friend. Don’t ask me who any of these people are: I haven’t a clue, beyond knowing that each is one of the several thousand people on my phone and email account’s contact lists. I learned these intimate details courtesy of a new and gorgeously designed app called Secret. Released two weeks ago and backed by Google Ventures, it allows users to anonymously share morsels of information with their friends and acquaintances.

Sometimes, these morsels are sweet—a photo of a finger adorned with a sparkly new engagement ring, maybe, or one of a home pregnancy test bearing a spot of good news. Sometimes, the posts are less innocuous: Last week, for example, someone who was identified as an employee of the popular note-taking application Evernote took to Secret and announced that everyone at the office was talking about the company soon being acquired. Which, naturally, caused an instant uproar, compelling the CEO to post a public denial. Similar gripes about bad bosses, bad investments, and bad karma abound, making Secret all anyone talks about these days in large swaths of the tech community.

To understand Secret’s immense appeal, it helps to consider it in context. Look at every other social-networking platform, and you learn that it depends primarily on volume. Tweets, Facebook status updates, etc., are like grains of rice, meaningful only when presented in mounds, which is why such platforms are designed to encourage users to remain continuously engaged and perpetually prolific. Secret is different. If Facebook is the information age’s equivalent of the 99-cent store, Secret is a Madison Avenue luxury boutique. It offers far fewer items, but each one has a much higher value: Enshrouded with the cloak of anonymity, users are free to transcend Twitter’s strained witticisms and Facebook’s pedestrian news feeds and offer each other candid, meaningful, and often brutally true dispatches.

And in a bit of inspired design, the more people vote favorably for a secret on Secret, the more likely is for that secret to travel outside of the original poster’s network and reveal itself to complete strangers far and wide. This long tail approach is unique to the social-networking ecosystem, addicted as it is to instant approvals and immediate likes. And it makes Secret’s offering far more potent and, one suspects, long lasting.

Some critics have already pointed out that the same design features that help Secret outshine similar existing services also open the app up to potential security disasters. “The big difference,” wrote one observer, “is that Secret offers this tantalizing clue as to where the dish came from. As more of your friends join, you’ll eventually see secrets from them or ‘friends of friends.’ By talking offline with a friend about what you both saw inside the app, you might be able to figure out who posted a secret in the first place. The key word there is might. The only way you’d know for sure is if you could find enough people with slightly different contact lists and eventually rule out people one by one.”

It’s a valid point, but it misses the bigger picture. Secret is potentially ruinous not only because a swirl of social engineering might reveal the identity of the person who posted a particular nugget, but because it continues, more effectively than any other service in recent memory, to sever the bond between information and responsibility. By dropping the pretense of visible usernames and public profiles and ensconcing all of its members in a nameless, faceless darkness, Secret is the living embodiment of that most pernicious adage of our age: “Information wants to be free.”

Except it doesn’t. Information is a commodity, one rendered even more precious by the fact that it is neither tangible nor exclusive. According to a recent government report, intellectual-property-intensive industries accounted for $5.06 trillion in value added in 2010, or 34.8 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. That being the case, the proper storage of and care for information becomes the primary challenge we must now face. In the wrong hands, as Edward Snowden has demonstrated all too well, information has the capacity to cause great damage to everything from the economy to national security. And Secret makes Snowdens of us all.

How might we resist? Leviticus offers a good general guideline. “Thou,” it commands us, “shalt not go up and down as a talebearer among thy people.” And Leviticus is hardly alone: Repeatedly, in the Bible and in Jewish liturgy, we are expressly warned of the perils of lashon hara. Of the 43 sins enumerated in Yom Kippur’s al chet prayer, for example, 11 are sins of speech. That the speech may in some cases be true hardly matters; it’s speech’s capacity to cause great harm that is considered paramount.

Which, of course, isn’t to say that talebearing is universally forbidden. When someone possesses knowledge that might deliver another from great harm, say, talebearing is a downright virtue. But understanding the intense pressures applied on the social fabric by secrets, rumors, and half-truths, Judaism has erected a structure dedicated to holding each of us responsible for his or her tongue.

As new applications seek to undermine this structure, we should reject the allure of the new for the wisdom of the ancient religion. There are few positions that come off as more dreary and uninspired in our tech-addled time than carrying on about the moral hazards of technology; and yet, when something like Secret comes along, we’ve hardly a choice. When our tools encourage us to speak without thought, care, or consequence, we would do well to be responsible and resist.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.