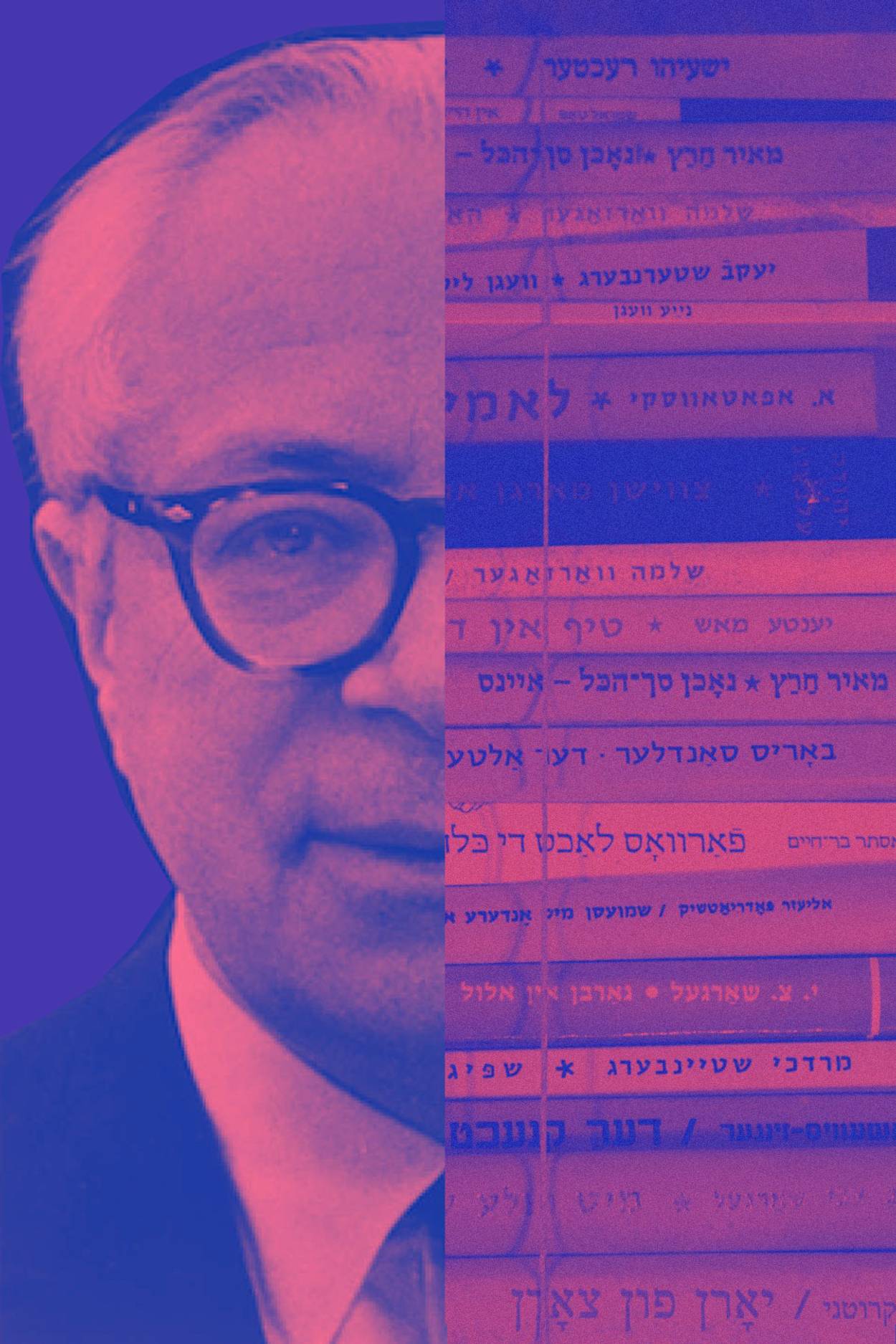

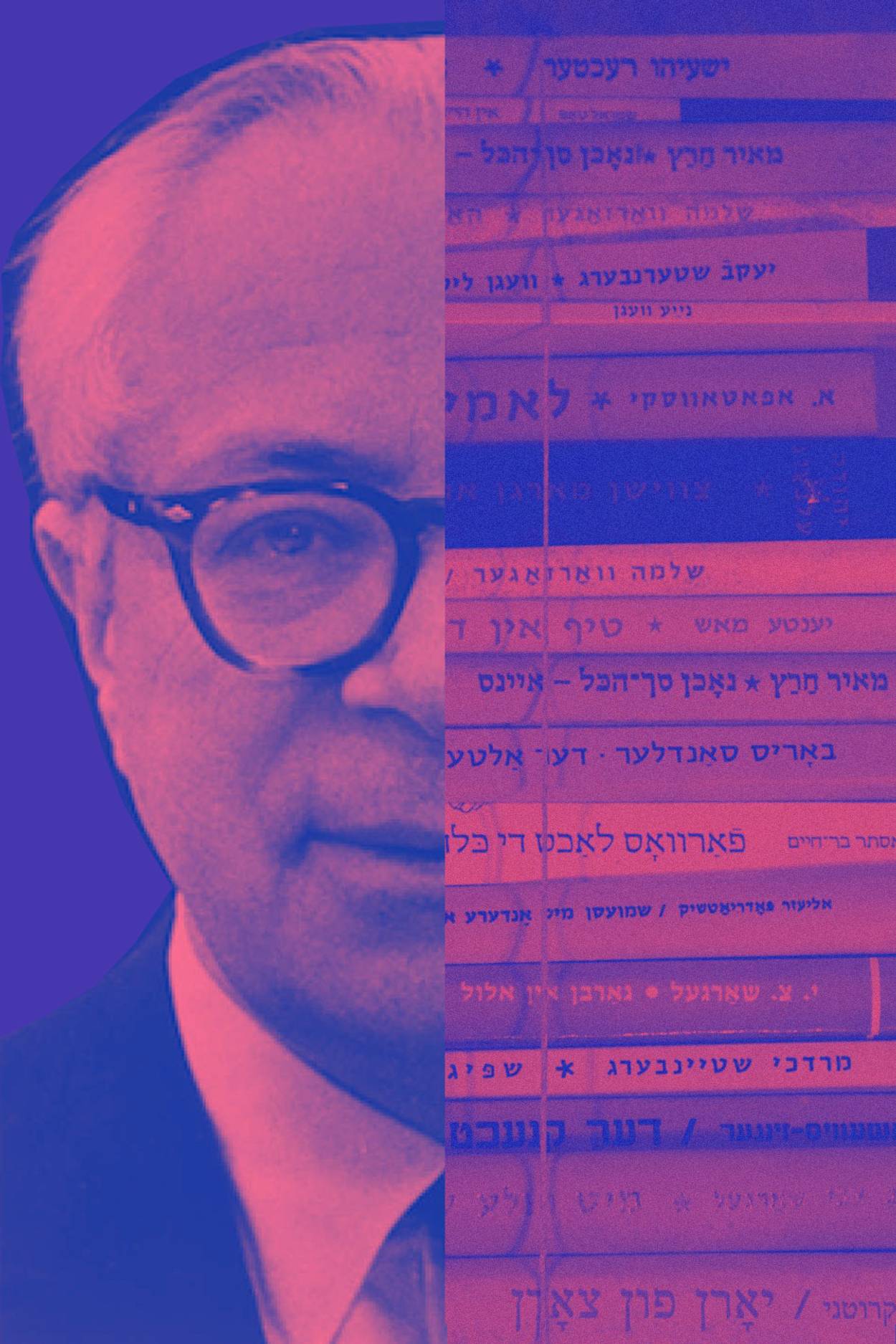

The Legend of Max Weinreich

The Jewish linguist hoped to make prewar Vilna into a secular Ashkenazi Jerusalem. Instead he became the greatest historian of Yiddish from his exile in New York.

Yiddish, the much maligned language of Ashkenazi Jewry, found its greatest champion and scholar at the 11th hour. Born the youngest of 10 children in 1894 in Courland, where Baltic German overlapped with Litvak culture, the linguist Max Weinreich grew up speaking German at home. But under the influence of his maternal grandparents, he became strictly observant from the ages of 8 to 11, until puberty, in his own words, “brought about a definite aversion for religion.” What precipitated the break is not hard to guess. Switching at the age of 9 from a heder metukan, a modernized heder, to a German gymnasium, young Max experienced his first attack of Yiddishkeit when he was bullied by his classmates, mostly children of the Baltic German nobility and Polish gentry. Transferring to a private Jewish gymnasium in Dvinsk, he befriended a member of the Kleyner Bund, who introduced him to Yiddish and Socialism. Thus was young Max caught up in the various isms that had taken the Jewish street by storm, beginning with the Bund, which took up the cause of the laboring, Yiddish-speaking masses. By age 13, he had begun writing from right to left; i.e., he switched from German to Yiddish, and from the politics of Jewish emancipation to social activism.

Like other Litvaks thirsting for secular knowledge, young Max headed for St. Petersburg, enrolling at the university and experiencing the Bolshevik seizure of power firsthand. Throwing himself into Jewish politics, he edited a student journal called Nash put’ (Our Path), and for as long as dissent was tolerated became a regular correspondent for the Bundist Yidishe shtime (Jewish Voice). It was in the cultural rather than the political arena, however, that Weinreich made his mark. When the literary monthly Di yidishe velt (The Jewish World), printed by the prestigious press of Boris Kletzkin, relocated from Petrograd (as St. Petersburg was renamed) to Vilna, Weinreich published the first-ever translation of cantos from Homer’s Iliad into Yiddish hexameters, so stunning a feat that it earned him a shoutout from the rising star of Yiddish lyric poetry, Moyshe Kulbak. “In every nation,” Kulbak wrote in “The Yiddish Word,” his essay-manifesto of 1918, “translations of Homer are a measure not only of that nation’s spiritual maturity, but also of the artistic development of its language, capable of rendering a writer such as Homer.” Beginning as a translator, Weinreich went on to master one body of knowledge after another in order to build the infrastructure for a Yiddish nation aborning.

Where to establish its capital, however, was never in question. While other social revolutionaries were notoriously peripatetic, and while Weinreich’s Wanderjahren would take him to Germany, Austria, and the United States in search of truth and scientific training, there was never any doubt in his mind that Vilna should become the center of a vibrant secular Jewish culture. Despite “forces that ripped us apart and precipitated linguistic degeneration,” he wrote in 1941, “a critical mass of Jews [in Vilna] spoke Yiddish as a matter of course.” They spoke a higher standard of Yiddish, he averred, “that led from Mendele to the YIVO”; were avid readers of the Yiddish press; and sustained a broad network of Yiddish schools, both elementary and secondary. “No wonder that visitors were amazed at how well and especially how naturally your average Vilna Jew used Yiddish when talking about lofty matters.” The ever-backsliding Jews of Eastern Europe might embrace Yiddish as their covenantal language only if Vilna were to become the New Jerusalem, complete with a Temple of Yiddish scholarship presided over by Levites and a High Priest.

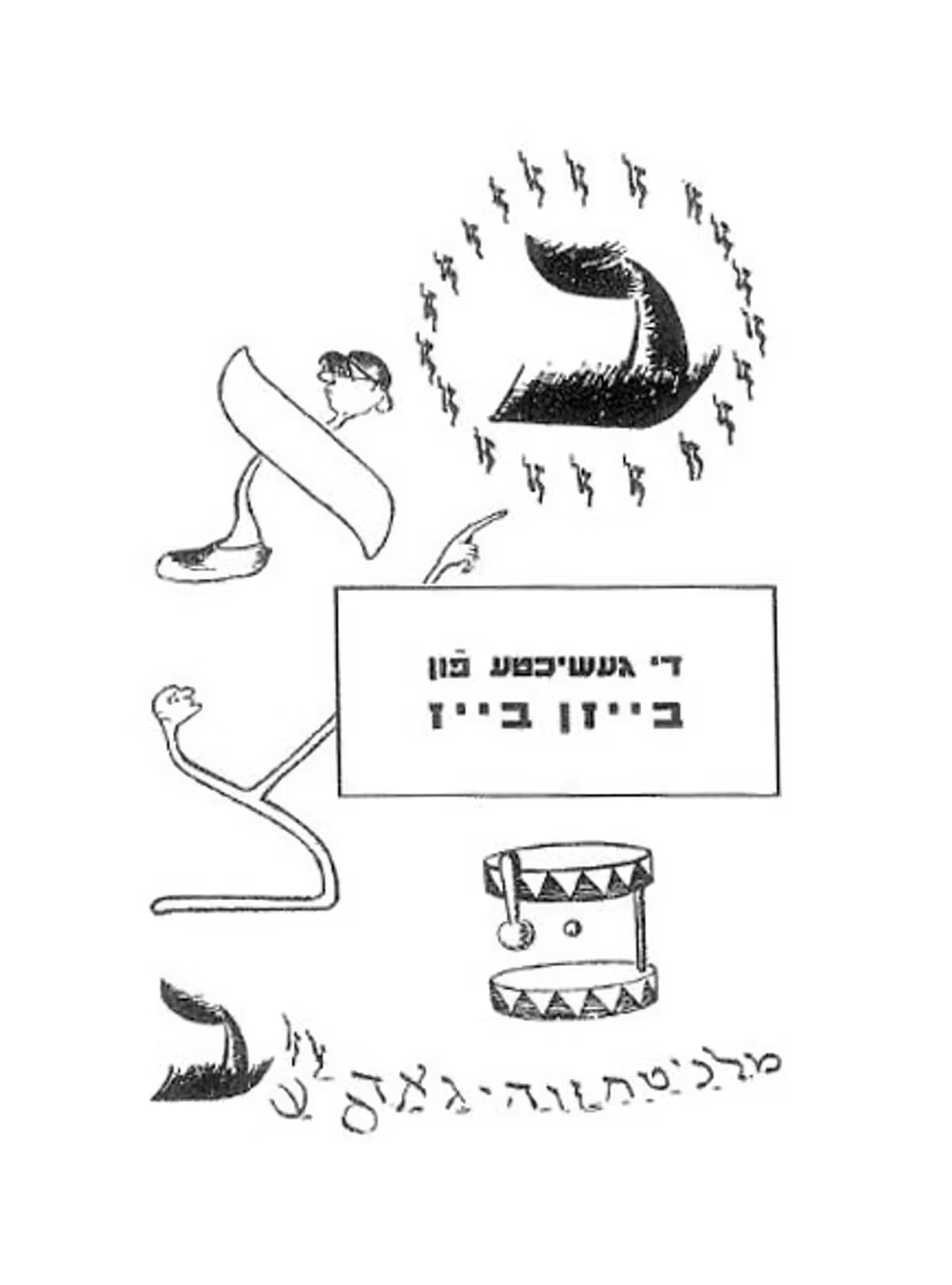

A kohen, in point of fact, who would have been the first male called up to the Torah had he ever stepped foot in a shul, Weinreich never capitalized on his priestly descent. Instead, he married into the Vilna aristocracy. His wife, Regina, was the daughter of Dr. Zemach Szabad, a revered public figure, who in his lifetime was immortalized by the Russian children’s writer Kornei Chukovskii as a friend of children and animals and lives on today in a life-size monument in the Old Town of Vilnius. Max took refuge in the Szabad residence during a pogrom carried out by the Polish Legion in April 1919, which may have been when he first met Regina. They married in 1923, the same year that Max completed his doctoral dissertation at Marburg on the history of Yiddish linguistics. Regina, a trained biologist, turned her energies to teaching Yiddish and raising a family. As their surviving son later recounted, Max had three children: the YIVO Institute for Scientific Research, born at a small gathering in Vilna on March 24, 1925; Uriel, born in 1926; and Gabriel, born two years later. Although Uriel was clearly his father’s favorite, Max made a point of always giving both boys presents on each of their birthdays, and when Gabby turned 7, Max wrote and typed up a children’s book called The Story of the Big Bad Beyz, illustrated and tinted in watercolors by the Vilna artist Khayim Munits, in which Gabby played the starring role.

Thanks in large measure to Weinreich’s determination, the Vilna Standard—the YIVO’s rules of standardized Yiddish orthography, officially adopted in 1936—became the new priestly code, and as a first step toward becoming a nation of priests, Yiddish-speaking Jews had to master Di shvartse pintelekh (1939), “the little black dots” of Hebrew script. This first publication in the YIVO’s popular series, richly illustrated, beautifully designed and written in a stylized folk Yiddish by Max Weinreich, was a new Scripture, which drew a direct line from scribal accuracy in ancient Egypt to the Vilna Standard. It was high time for the People of the Book to go back to school.

The proper spelling of Yiddish was contentious precisely because only yesterday there had been no standardized Yiddish orthography, and therefore no way to distinguish one rival camp from another. Now that the battle lines were firmly drawn—between the Soviet Socialist Republics to the east and the newly carved out nation states to the west; between the Orthodox and the militantly secular—how you spelled became the surest way to prove your bona fides. The Vilna Standard demanded that the etymological spelling of the Hebrew-Aramaic component of Yiddish, the most ancient stratum of the language, be preserved, for this is what all Jewish languages had in common. Soviet Jewish language planners thought otherwise. To achieve universal literacy while eviscerating rabbinic culture, dismantling heder education, banning religious observance and driving a permanent wedge between the Soviet working classes and petty-bourgeois nationalisms, the Soviet state apparatus mandated a naturalized system of spelling in which all Yiddish words were treated equally. By eliminating such “superfluous” letters as veys, khes, sof, tof, used only in Hebrew-Aramaic-origin words, followed by the abolition of the final letters khaf, nun, fey and tsadik, any Yiddish text printed outside the Soviet Union was rendered indecipherable. Not just ritual purity lay in the details; the devil too.

The devil rearing his ugly head was fascism, on the rise even in the temple grounds of Yiddish. Since 1921, Vilna-Wilno had become part of the Polish Republic, and ultranationalist students and their sympathizers went on a two-day anti-Jewish rampage in November 1931, while the police did nothing to stop them. Returning from a press conference hastily convened by the provincial governor, Weinreich was beaten over the head and lost sight in his right eye, just when he needed it most. That year, the YIVO launched its flagship publication, the YIVO-bleter, under the joint editorship of Weinreich and his fellow linguist and Litvak Zelig Kalmanovitsh. Correcting the spelling was the least of it. To use Yiddish when writing about lofty matters meant that Weinreich had to invent (or repurpose) hundreds of terms for each discipline and spend countless hours not only rewriting, but in many cases, translating, each submission. Summing it up years later with one of his typical bon mots, Weinreich told his readers that visnshaft, science, was aza min visn vos shaft, the kind of knowledge that creates. The most creative scholarship was for the people, about the people, and in the people’s embattled language.

Carrying the stigmata of his Polish Jewish identity; living the double life of scholar and journalist; raising two healthy, inquisitive, boys; ready to assume the high priesthood of Yiddish in its self-proclaimed capital and its temple—at this critical juncture, Max Weinreich’s life took a decidedly Hasidic turn. For in every great mystic’s biography, the stage of “self-revelation” always goes hand-in-glove with a period of spiritual retreat, called praven hisboydedes, or “going into seclusion” somewhere off the beaten track. For Weinreich, that place of retreat was Yale University, at the farthest possible remove from Jewish Vilna. This is where he spent the 1932-33 academic year as one of 13 scholars in the social sciences chosen as Rockefeller Foundation fellows to attend the International Seminar on the Impact of Culture on Personality, led by Edward Sapir and John Dollard. After emerging from this intensive seminar, Weinreich would not only change his own direction and that of his institute but also throw a lifeline to a generation of Eastern European Jews that had lost its way.

In every great mystic’s biography, the stage of ‘self-revelation’ always goes hand-in-glove with a period of spiritual retreat. For Weinreich, that place of retreat was Yale University.

The focus of Jewish social science in Vilna had been saving and preserving the material and spiritual culture of Yiddishland—everything from folk art, recipes, folk medicine (remedies and exorcisms), folk meteorology (fortune telling, omens), children’s lore (counting-out rhymes, circle dances, riddles), to Purim plays, folktales, jokes, songs and proverbial sayings—around which an army of zamlers, amateur collectors, had been mobilized. Just before leaving for Yale, Weinreich had called upon Polish Jews to systematically study everyday life, beginning with the Polish shtetl. The Yale seminar, in stark contrast, cast aside the salvage ethnography of intact cultures in favor of much more immediate social concerns. High on the reading list were the social scientists who had come out the University of Chicago, like Sapir, Louis Wirth and L.K. Frank, with their emphasis on the social and psychological dynamics of acculturation in contemporary societies. No less innovative was the use of auto-ethnography. The Yale seminar was designed to be a collaborative venture in which the participants, carefully chosen to represent distinct countries and cultures, were to act in a triple capacity: as scholars, informants and students. Where but in America would a roomful of highly credentialed male academics be expected to turn itself into the precursor of a 1960s encounter group? At Yale, ethnography merged with psychoanalysis; streamlined for a seminar, the psychiatrist’s notebook was replaced by the analytic questionnaire.

And so, on Feb. 3 and April 19, 1933, Max Weinreich filled out two detailed questionnaires, the first on the Eastern European Jewish family, the second on Jewish religion. For this analysand, the difference between these two assignments could not have been more pronounced—and more revealing. Weinreich was on native ground when he unpacked Yiddish proverbs and popular sayings that bore on the subject of family dynamics, child rearing and ethical instruction, even while claiming that “I myself don’t use this tool of education.” When it came to Jewish religion, however, Weinreich’s uncompromising secularism got in the way of objective analysis. In his judgment, “religious feelings” were in steady decline among all sectors of Polish Jewry, and within the closed system of Orthodoxy, there was no freedom whatsoever, neither in matters of observance nor interpretation. For all that, apostasy, from the perspective of modern Jews like himself, was national treason; from the folk perspective, it was simply laughable. Weinreich wrote with open sarcasm about the efforts of Christians to missionize the Jews of Vilna and about Jews who succumbed to baptism. In the last analysis, placing culture and religion into separate categories did not fit the facts on the ground, because culture, religion, peoplehood and politics were indivisible when it came to the Jews of Eastern Europe, and only when taken together could their impact on the Jewish personality be accurately measured. Axiomatic to the questionnaires, however, was that identity formation started in early childhood and came to a head in adolescence.

As in the folktale, the lone hero returned from his adventures in possession of a magical agent; not with the secret source of mystical knowledge as in the Hasidic tale, but with keys and stratagems to rescue the princess in the tower. Making a brief stopover in Vilna to lecture on the foundations of Jewish youth research, Weinreich picked up Regina and the boys and moved with them to Vienna, where he spent several months studying with Charlotte Bühler, the eminent psychologist who specialized in early childhood and adolescence, and befriended Dr. Sigmund Bernfeld, founder of the Jewish Institute for Youth Culture and Education. Now positioned to bridge New Haven and Vienna, youth research and psychoanalysis, Weinreich came home to the finally completed YIVO building at 18 Wiwulski Street in the upscale part of town. As the first order of business, the YIVO established the “Dr. Tsemakh Szabad-aspirantur,” a graduate-level training program to educate aspiring scholars and to imbue them with the social purpose of scholarship. Without stipends and oversight, there could be no discipleship.

To face the future, Jewish youth had to know themselves, and it was up to the YIVO to give them a voice.

The second order of business was to launch YUGFOR, short for yugnt-forshung, the Division of Youth Research, to study the problems of contemporary Jewish children and adolescents from an interdisciplinary perspective. “Youth”, as defined by Weinreich, began with political awakening, for in the wake of the First World War there was nary a girl or boy who did not belong to one or another youth movement—or switch from one movement to another. To face the future, Jewish youth had to know themselves, and it was up to the YIVO to give them a voice. At Weinreich’s initiative and with the tools he had picked up in Vienna, the YIVO announced and publicized a series of autobiography contests for Jews between the ages of 16 and 22. In the first round, 34 young people from Vilna and the Vilna region responded, but the second contest, held in 1934, attracted 304 entries from 12 countries—a spectacular and totally unanticipated response. No less stunning is what Weinreich made of them.

The Path to Our Youth: Elements, Methods, and Problems of Jewish Youth Research (1935), with a table of contents in Polish and English, was Weinreich’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man. Unlike anything he had ever done, it was written in a Yiddish all his own, and adhered to a structure that was at once rigorous, comprehensive and open-ended, the “problems” outnumbering the “elements” and “methods” three-to-one. Cutting-edge science—everyone from Havelock Ellis, Anna Freud and Ernest Jones to Margaret Mead, Franz Boas and Melville Herskovits—cast a harsh light on this new terrain, for which a new (and cumbersome) term was needed, dervakslingshaft, or “adolescence.” Yiddish was both the book’s medium and message; it could not have appeared in any other language. Amid the barrage of racial pseudoscience, no German Jewish scholar would have dared expose autistic, psychotic and neurotic behavior among the Ostjuden to public scrutiny, nor would any social scientist in 1930s America have had the chutzpah to lump Jewish youth together with Delinquency Areas in Chicago. Zionist scholars writing in Hebrew, moreover, would have ridiculed the book’s concluding argument, that Polish Jewish youth were better advised to work through the multiple traumas of their Jewishness than escape to Palestine.

To promote one of his newly acquired “methods,” Weinreich turned next to the serial publication of Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, in an authorized translation that ranked, if anything, as a greater cultural achievement than his pilot translation of Homer. Empowered by modern science and mediated by Max Weinreich, Jewish youth were poised to be emancipated from their multiple disabilities—just when the temple of Yiddish was destroyed.

What happened next resembles nothing so much as the legendary life of the first-century sage, Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai. Before the destruction of the Second Temple, he was the voice of the embattled Pharisees. After the destruction, he was the sum total of what could still be salvaged. In between, as Jerusalem was under siege, he escaped in a coffin carried by his two most trusted disciples, who brought him before Vespasian, the Roman military commander. “I ask for nothing,” said Yohanan to Vespasian, “except Yavneh. I will go and teach therein my disciples, and I’ll establish therein prayer, and I’ll perform therein all of the duties prescribed in the divine Law.”

The rabbis, who used stories primarily to punctuate their case law, didn’t tell us what happened to Rabban Yohanan’s wife, children, mother-in-law or library. But we know all this about Max Weinreich’s escape to America: As a bar mitzvah present, Uriel’s parents took him along to the International Conference of Linguistics in Brussels, via Copenhagen. But when Hitler and Stalin signed a nonaggression pact and the conference was canceled, Regina rushed home to Gabby (as she had promised her mother, Stefania Szabad, to do) while Max stayed behind with Uriel to take in the sights before setting sail with him for New York in March 1940. Vilnius, meanwhile, briefly became the capital of independent Lithuania before the Red Army marched in a second time. The Soviets requisitioned the spacious and elegant Weinreich apartment, at which point Regina transferred Max’s library to the YIVO building, a huge and carefully cataloged collection that the Germans eventually plundered. Regina and Gabby finally escaped through the Far East and were reunited with Max and Uriel at the end of January 1941. Stefania, they learned much later, perished with the last remnant of the Vilna ghetto in September 1943.

During these years of separation, uncertainty, tragedy and catastrophe, Max Weinreich was the programmatic leader of the YIVO and the commanding voice in what was left of Yiddish scholarship. Without missing a beat, volume 15 of YIVO-bleter appeared in New York, a unilateral decision on Weinreich’s part that caused much alarm back in Vilna, and just as seamlessly, he announced an autobiography contest in 1942 for middle-aged and elderly Jews to chronicle their immigration to the United States. Every January, at the YIVO’s annual banquet, he delivered a substantive, well-crafted and extremely cogent keynote address—“Jewish Scholarship Today” (1941), “The YIVO in a Year of Upheaval” (1943), “The Place of the YIVO in Jewish Life” (1944)—that made the case for New York becoming Yavneh, especially after 1942, when the institute moved to its own building at 531–535 West 123rd Street, the former Schiff mansion.

Weinreich embodied the YIVO’s resolve to relocate its center to America. And why not? The Jewish heartland was no more, the temple was in ruins, and Yohanan ben Zakkai had made his escape—not once, but four times over. With the arrival of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn in 1940 and his son-in-law, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, a year later, Chabad Hasidism was rebuilt from scratch at 770 Eastern Parkway. With the rescue of Rabbi Aharon Kotler, in 1941, the Lithuanian yeshiva was reconstituted, not in Brooklyn but in the relative seclusion of Lakewood, New Jersey. Max and Uriel Weinreich were joining a wave of iconic Litvaks resettling in the New World.

By the time Weinreich arrived in America, his inner life was in utter turmoil.

Yet by the time Weinreich arrived in America, his inner life was in utter turmoil. He refused to abandon Vilna. True, there had been some ground for optimism in 1940, when he had been nominated to become chair of Yiddish language and literature at Vilnius University, but after the Red Army marched back in, in June 1940, the YIVO was renamed the Institute of Jewish Culture and was made part of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania. Only the most attentive members of his audience at the annual New York banquets could read Weinreich’s lips. “Are we betraying the Vilna YIVO by moving into our new permanent quarters in New York City?” he asked parenthetically in January 1943. Speaking a year later, in a sentence whose convoluted syntax betrayed his angst, Weinreich still maintained “our mystical hope that it is inconceivable that everything [we built] will have been annihilated.” When Weinreich spoke of mystical hope, the ground under him must have been shaking.

To save the essential core of Judaism—prayer, Torah and rabbinic authority—Rabban Yohanan had entered the enemy camp. Driven by the same desperate need to start over, our four Litvak leaders headed for the United States, a spiritual wasteland akin to Rome. When Weinreich spoke Yiddish he spoke from the cultural high ground, for he viewed American Jewry as inchoate and considered its youth to be atomized and unmoored. “Give me a hundred young people in the next five years,” he proclaimed in January 1944, “and I’ll rebuild Jewish America!” Yet while the New World proved fertile ground for the Lithuanian rosh yeshiva and the charismatic zaddik to reassert their positions of spiritual leadership, the same was not true for the dean of Yiddish scholars. Vilna-on-the-Hudson was never to be. Instead of drawing a hundred disciples nearer, Weinreich would have to make do with ten.

For public consumption, every issue of News of the Yivo, from then until today, carried feature stories about the retrieval of lost cultural treasures, but from his new home on Payson Avenue in the Inwood section of Manhattan, Max Weinreich spent every waking hour counting his losses—and seething with rage. By 1948, the Soviet-Yiddish experiment was over and those who had once attacked him were long dead—Nokhem Shtif, mercifully, died at his desk and Max Erik slashed his wrists in the gulag.

In retrospect, however, the wars of the Jews were as nothing when compared with the war against the Jews waged by Hitler and his henchmen, the most notorious of whom were prosecuted at Nuremburg. As yet unindicted were a second tier of loyal Nazis and enablers—Germany’s finest; scholars, thinkers and researchers, some world-renowned. They were the most insidious servants of evil, for scholarship in the service of the Nazis was a double betrayal. Besides aiding and abetting Hitler, Weinreich held them responsible for defiling, perverting and destroying the very integrity of scholarship itself, the ideal of dispassionate visnshaft that only yesterday had been the beacon of Jewish self-emancipation. Hitler’s Professors: The Part of Scholarship in Germany’s Crimes against the Jewish People (1946) appeared in Yiddish, then again as the first volume in the YIVO English Translation Series. In it, Weinreich tracked the careers of such luminaries as professor Dr. Martin Heidegger and Hans Naumann, a criminal docket that was alphabetically searchable in the Index of Persons and Institutions. For Weinreich, as for Abraham Joshua Heschel, who read Hitler’s Professors in the Yiddish original, some of these German scholars had been mentors, thesis advisers, and trusted colleagues. So on the day when Weinreich completed the manuscript, March 15, 1946, he asked his personal secretary, Chana Gordon, for a cigarette, a pleasure he had denied himself all through the war. She watched Dr. Weinreich light up and take a few richly deserved puffs; then, without finishing, he put it out.

Among the saving remnant, none was more precious to Weinreich than the Vilner, the Yiddish blue-bloods like Benjamin Hrushovski, Mikhl Astour and especially Abraham Sutzkever, who managed to smuggle the most valuable parts of the Vilna ghetto archive from under the watchful eyes of the Soviets and began mailing them piecemeal to New York. “There are no words,” Weinreich wrote to thank Sutzkever, newly arrived in Paris, “to express our emotions. And I want you to know that these emotions are felt not only by actual Vilner. The whole of YIVO in New York is an institute of Vilner, and we will do everything in our power to Vilnaize Jewish life here.” That was Weinreich speaking in the first person plural. Speaking in his own name, with absolute candor, because Sutzkever’s decision whether to move to New York or Tel Aviv hung in the balance, Weinreich delivered his sober assessment of the true state of Yiddish culture in America. What he saw were Yiddishist circles suffering from exhaustion, defeatism and self-satisfaction, coupled with the fear of rocking the boat. The only hope was to win back alienated American Jewish youth—if only the YIVO weren’t running a huge deficit, just like the old days, in Vilna. Israel, he advised Sutzkever, was no panacea either, so perhaps America still remained the land of opportunity. Sutzkever, as astute a reader of people as he was of poetry, made the right choice and, with Golda Meir’s help, emigrated to Mandatory Palestine.

Like Sutzkever, who faced myriad obstacles after making this fateful decision to emigrate, Weinreich had decisions in front of him that would determine the future course of Yiddish studies. Should he accept the invitation of professor Ben-Zion Dinur to occupy the first chair of Yiddish literature at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem or stay in New York? Citing his responsibilities to the YIVO, Weinreich turned the offer down, and the chair went to Dov Sadan, who lacked academic credentials but had the right ideological (read: Labor Zionist) profile. When Frank Z. Atran, at the opposite end of the Jewish political spectrum, announced the Atran chair in Yiddish to be established at Columbia University, should Weinreich be the first incumbent or continue teaching in the German department at City College? Weinreich used his professional contacts to persuade Columbia to accept in his stead a newly minted Ph.D., the extremely promising young linguist, Dr. Uriel Weinreich, at a lower rank and salary. But the most momentous decision is the one he admitted to Sutzkever alone, in July 1950, to recuse himself from administrative responsibilities at YIVO and devote his best efforts to writing the history of the Yiddish language as it related to the social and cultural history of Ashkenaz as a whole. This Weinreich did every day for the next 16 years.

Weinreich’s grand narrative, History of the Yiddish Language: Concepts, Facts, Methods, began in the year 1000 in a tiny area called Loter along the River Rhine, now reimagined as the cradle of Ashkenaz, with its own communal structure, laws, liturgy, customs, folklore and linguistic synergy. Ashkenaz in turn drew its strength from an all-embracing rabbinic culture he called the Way of the Shas, that was launched not in Jerusalem but in Yavneh.

Like Joyce’s Ulysses, Weinreich’s masterpiece ranged effortlessly over the entire historical, cultural and literary expanse of the language, drawing on all its stock languages, dialects and forms of self-expression. It featured a dizzying cast of characters (living but mostly dead) and was written in a rigorously concise and self-consciously artful style that no one else could possibly replicate. “Hotseplots and Boyberik have real non-Jewish equivalents in Silesia and eastern Galicia,” Weinreich explained to illustrate the uniqueness of Jewish geography, “but among Yiddish speakers they are places in the world of fantasy” (3.5.1). In Yiddish, the last phrase reads: “ober bay yidish-reyders zaynen dos ergetspunktn in dimyen” (46.1). “Ergetspunkt,” most probably coined by Weinreich, makes one think of Never-Neverland, and when yoked together with the Hebraic “dimyen” sounds like a line of modernist verse. And since the History was also designed to be a primer in what Weinreich called “component-consciousness”—the Yiddish-speaker’s innate awareness of the Hebraic, Germanic, and Slavic components that together made Yiddish into a ”fusion language”—he worded every sentence to heighten that awareness.

So who was Weinreich’s imagined reader? Hearing from Weinreich how reluctant the YIVO was to publish his unwieldy manuscript, Sutzkever, who happened to be in town on a speaking tour, convened a three-way meeting with Yudl (Julius) Borenstein, the chairman of the YIVO board. When Borenstein offered to publish the text without the notes, Weinreich sat there “with downcast eyes” and retorted: “Only 10 people will read this work, and these 10 will need the notes!” Sutzkever prevailed, but Weinreich never lived to see its publication, let alone the second English-language edition that had all the notes and the long-awaited index.

Had the heartland of Yiddish not been destroyed; had Max Weinreich not been forced into exile; and had Jewish youth not found other paths, there would have been no History of the Yiddish Language. Were it not for the annihilation, there would have been no Book of Ashkenaz.

Weinreich offered Ashkenaz as a new myth of origins. No longer the misadventures of the missing letter beys, this work retraced the early medieval roots of Yiddish through the elusive protovowel alef. The largest, most dynamic, most pluralistic Jewish community of all times, especially its Eastern European branch, Ashkenazic Jews, he demonstrated, never lived in ghettos. What Ashkenaz achieved was not isolation from the Christian world but insulation from Christianity. No longer would Weinreich need to convince his readers of how impoverished Yiddish would be without Hebrew and why the etymological spelling of the Hebrew-Aramaic component needed to be preserved. Ashkenaz was a model of internal Jewish bilingualism, a complex symbiotic system of the written and spoken languages of the Jews going back to the decline of Hebrew as a spoken language in Palestine. Throughout the diaspora, moreover, Jews spoke their own language; therefore, Yiddish studies could be in the forefront of a whole new discipline he called Jewish interlinguistics. No longer would Weinreich complain that Orthodoxy was a closed system that allowed no freedom either in matters of observance or interpretation. Quite the opposite was true. Within the Ashkenazic culture system “the highest form of literary creativity is the commentary.” And so The Book of Ashkenaz came with its own commentary: two volumes crammed with notes, each one the subject of a graduate thesis still to be written.

The four-volume boxed-set edition of Weinreich’s Geshikhte fun der yidisher shprakh—two volumes of text plus two volumes of notes minus the index volume that never appeared—is the most capacious, original, carefully crafted and meticulously proofread, single-authored work ever to appear in the Yiddish language. Like a seyfer, a sacred tome, it was designed to last forever.

David G. Roskies is the Sol and Evelyn Henkind Chair emeritus in Yiddish Literature and Culture and a professor emeritus of Jewish literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary.