Leonard Cohen’s Songs of the Yom Kippur War

In an appearance that has never quite been explained, the legendary singer came to the desert to perform for the troops during one of the bloodiest weeks of the battle

There was always something cryptic about “Lover Lover Lover,” the 1974 classic by the Canadian music icon Leonard Cohen, the “poet of rock.” The song might not be as famous as Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” but it was beloved by fans and important to the singer, who was still playing it in concert four decades later. But what did it mean? Why, in the song’s first line, did he cry “Father, change my name”? That didn’t sound like a love song. Neither did the observation that a body could serve as a “weapon,” or the hope that the song itself would serve as a “shield against the enemy”? Who was this enemy? And who was the audience?

In 2009, Cohen ended a world tour with a show in Israel, where I live. At 75, he put on one of the greatest last acts in music history. This came after he’d emerged from a Buddhist monastery in California to find that a former manager had cleaned out his bank account, went back on the road, and discovered that he’d ascended to the pantheon of popular music. Maybe you were lucky enough to catch one of those concerts. I grew up in Canada, where Cohen has always been considered a national treasure, but until then I hadn’t quite appreciated that his status in Israel was the same. When tickets went on sale here the phone lines crashed within minutes. Fifty thousand people showed up in Tel Aviv.

I didn’t know the reason for the intense connection until an article in a local paper suggested one explanation. It had to do with an experience Cohen had shared with Israelis long before, in the fall of 1973. My attempt to figure out what happened turned into years of research and interviews, and eventually into a book called Who By Fire, which is about how a war and a singer collided to create an extraordinary moment in music. One strand of this story turned out to be linked to “Lover Lover Lover,” and to the struggle of a great artist, or of any of us, to reconcile the pull of the universal with the magnetism of our own particular tribe and past.

The second week of October, 1973, was one of the worst in Israel’s history. At 2 p.m. on October 6, which was the Jewish fast day of Yom Kippur, Egypt and Syria launched surprise attacks. Sirens sounded across Israel, an Egyptian bomber fired a guided missile at Tel Aviv, the border defenses crumbled, the air force began hemorrhaging planes and pilots, army fatalities climbed from the hundreds into the thousands, and Israelis were struck with despair. At that moment, out of the smoke of battle in the Sinai Desert, on some quest of his own devising, strode a wry bard from Montreal.

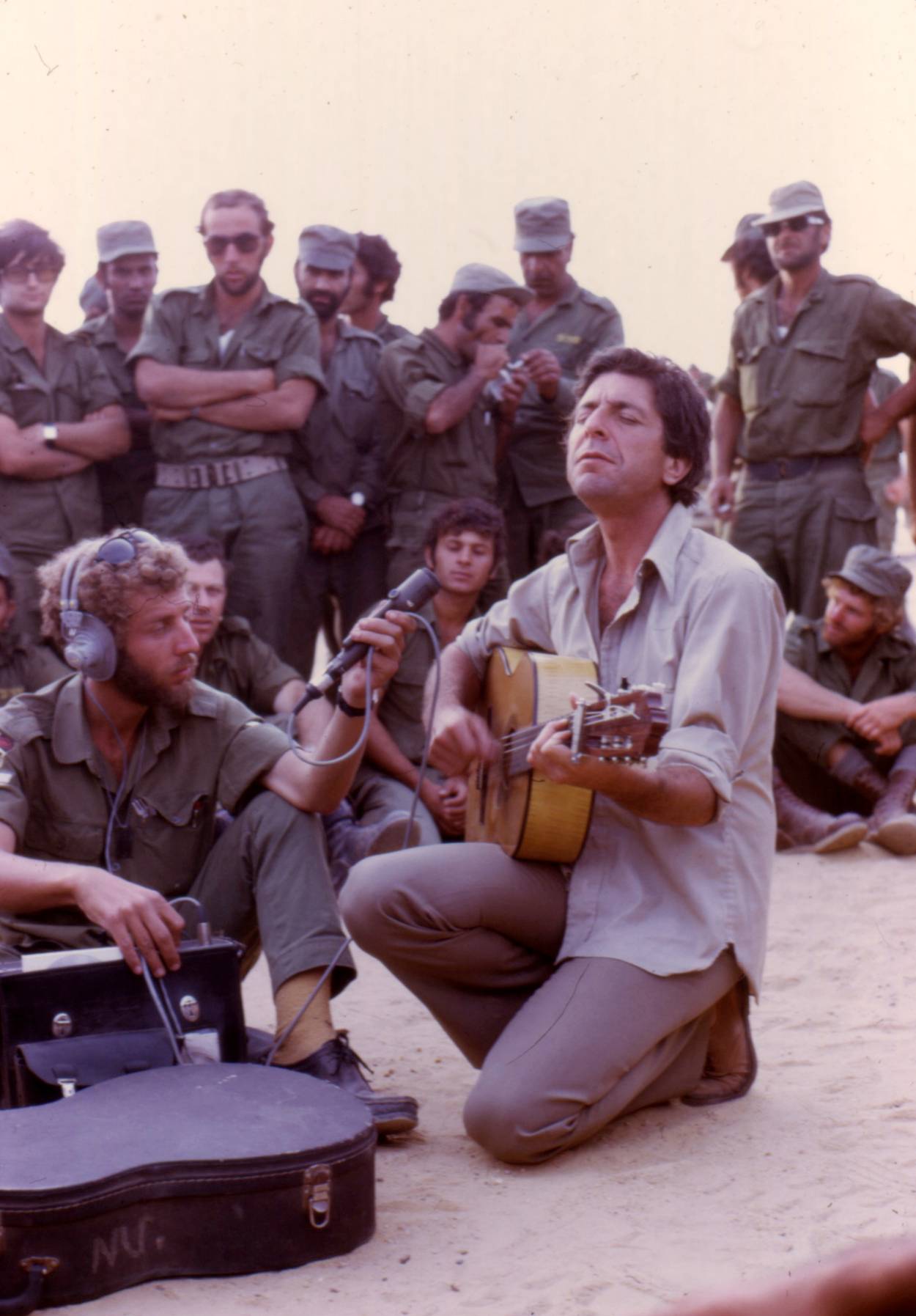

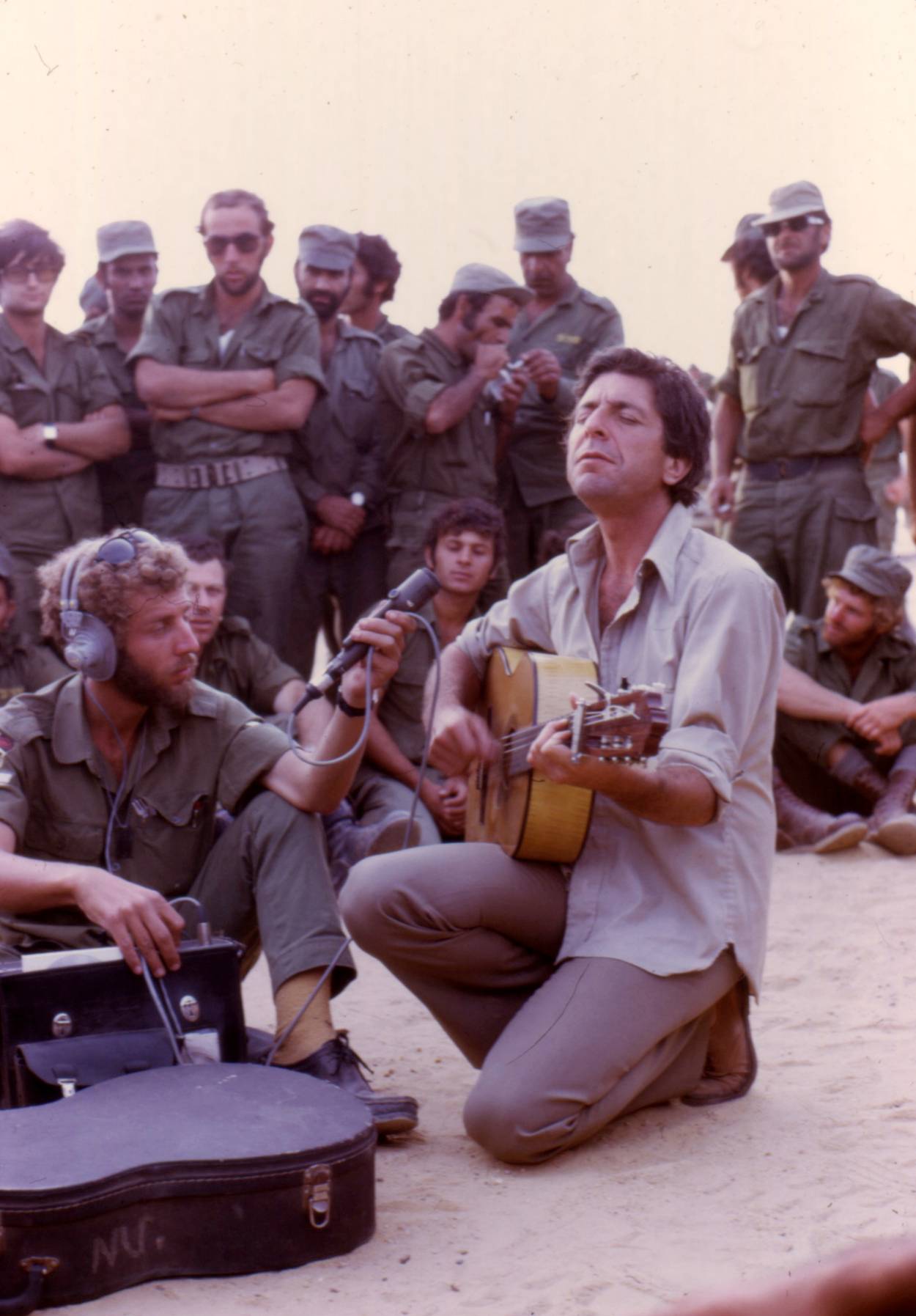

Leonard Cohen’s appearance seemed as strange then as it does now, and has never really been explained, although in Israel this has become one of the stories everyone knows about the Yom Kippur War, just like the famous battles. Cohen was already an international star. Three years earlier he’d played for a half-million people at the Isle of Wight festival, which was bigger than Woodstock, and where wild fans heckled Joan Baez, threw bottles at Kris Kristofferson, and burned the stage with Jimi Hendrix on it, but settled down when Cohen came onstage after midnight and hypnotized them. He was one of the biggest names of the Sixties. And now here he was in the Middle East, at the edge of a desert strewn with blackened tanks and corpses in charred fatigues, playing for small groups of soldiers without an amplifier and with an ammo crate for a stage. Some soldiers didn’t know who he was. Others did and couldn’t understand what on earth he was doing here.

How he got to the war and what drew him, or drove him, to Israel is a different story, one which I unraveled with the help of a remarkable manuscript he wrote about the experience and then shelved. By the time he reached the front in Sinai, he was with a pickup band of four Israeli musicians. In one description from a long-defunct magazine that was the Israeli equivalent of Rolling Stone, soldiers were sitting on the sand at night after a day of fighting. Some of them smoked. Cohen arrived wearing khaki. He addressed them in solemn English, which not all of them understand. “This song is one that should be heard at home, in a warm room with a drink and a woman you love,” he said. “I hope you all find yourselves in that situation soon.” He played “Suzanne.” The audience for this strange tour was a cross-section of young Israelis at the worst moment of their lives—shaken infantrymen, half-deaf artillerymen, teenage girls from a destroyed radar station who’d just seen five friends killed. I spent a lot of time tracking them down to hear how it felt.

One of the concerts was at an air base called Hatzor, where pilots flying American Phantom jets and French Mystères were being shot down by Soviet SAM missiles at a rate the Israeli air force had never seen. Pilots would zip up their flight-suits, leave their quarters, and vanish for good. This tour drew its unique potency from the fact that a singer whose themes were human imperfection and transience, and the brief pleasures that can sweeten your night, found himself playing for people for whom those fleeting forces weren’t abstractions floated into the air of a dorm room. They knew death was waiting for them when the concert ended. Everyone was sober. No money changed hands. People were paying attention.

At the air base, Cohen played the hits that everyone knew, “Suzanne,” “So Long Marianne,” “Bird on the Wire.” The show went over so well that one of the officers begged the musicians to perform again, and in the break between the two performances Cohen wrote a song.

One of the pleasures of researching this book was spending time with the pocket notebooks Cohen kept during and after the war, preserved by the singer’s estate. Here I found scribbles, half-thoughts, throwaway lines, and the first glimmers of songs eventually known to millions. On one page of a little orange notebook that he had with him in Israel he wrote (and your breath catches, if you know Cohen’s work, because you’re watching the birth of something famous):

I asked my father I asked

him for another name

It’s the embryonic version of “Lover Lover Lover.” It’s an interesting idea to open with, especially since the Israelis say that Cohen asked to be called not Leonard but Eliezer, his Hebrew name.

Cohen introduced the song in the second show at the air base, according to two of his bandmates—the balladeer Oshik Levy, who was standing by the stage listening, and Matti Caspi, the 23-year-old who played guitar on the very first rendition of the song, now an Israeli music legend in his own right. Cohen fine-tuned it as the band progressed through the war. In his unpublished manuscript, Cohen mentions the idea that he could actually keep the soldiers safe: “I said to myself, Perhaps I can protect some people with this song.” That might explain the lyric about the song being a “shield against the enemy.”

So “Lover Lover Lover” is a war song. It’s not clear what “lover” he’s referring to in the chorus, which simply intones that word seven times and implores, “come back to me.” But if we understand the song as a kind of prayer, maybe the word appears in the sense of the biblical Song of Songs, where God’s presence is described in terms of erotic love. Few require this presence as urgently as soldiers. Cohen grew up in a Jewish community, the grandson of a learned rabbi, and he knew the Bible (and knew the erotic parts, one senses, better than the others).

Or maybe it’s just a classic war chorus, an expression of longing for someone far away, like Konstantin Simonov’s “Wait For Me,” the favorite poem of the Red Army frontoviki of World War II. In that song each verse starts, “Wait for me and I’ll come back.” Cohen’s mother, Masha, was a native Russian speaker, and maybe she sang him Simonov when he was a child in the years of the world war. Anyone who’s been a soldier knows that sentiment is the most powerful one, far more than patriotism or anger. Researchers studying the music of GIs in Vietnam found that although movies after the war made it seem like the in-country soundtrack was political, with songs like “For What It’s Worth” and “Fortunate Son,” the songs the troops actually loved were the ones about loneliness and longing, like “Leaving on a Jet Plane.”

A mysterious detail in the story of “Lover Lover Lover” first appeared when I interviewed Shlomi Gruner, who in 1973 was a young officer in a makeshift unit of infantrymen who saw some of the toughest fighting in Sinai. He and his friends were on the far side of the Suez Canal one night, camped under a tent made from the parachute of an Egyptian pilot they’d shot down. He was out combing the desert for gas for the unit’s jeep, coming back empty-handed, when he saw a figure with a guitar sitting on a helmet turned upside-down on the sand. He knew the voice; Leonard Cohen was here. This made no sense, but it was true. He was singing “Lover Lover Lover.”

When we spoke, Shlomi particularly remembered one verse that identified with the Israeli soldiers, calling them “brothers.” At the time, the Arab states were arrayed against Israel, and most of the countries of Europe were refusing even to allow supply flights to refuel on their way here. Israelis had a feeling of acute isolation. It touched him to know that someone like Cohen had come all the way to Israel and traveled to Sinai to be with them. The singer wasn’t a plane full of weapons or reinforcements, but his presence meant something, and so did his words: “brothers” left no room to speculate about where Cohen stood. The problem is that there is no such verse in the song.

At first I thought Shlomi was mistaken. Memory is an unreliable resource, particularly in moments of extreme stress, as I know from my own experiences in uniform. But then I found a newspaper article, published in an Israeli daily during the war, in which the reporter noted that Cohen had just written a new song called “Lover Lover Lover” and quoted a verse that sounded like the one Shlomi was talking about.

It was Cohen’s little orange notebook that solved the mystery. After the first draft of “Lover Lover Lover,” under the heading, “Air Base,” eight lines appear in the singer’s handwriting:

I went down to the desert

to help my brothers fight

I knew that they weren’t wrong

I knew that they weren’t right

but bones must stand up straight and walk

and blood must move around

and men go making ugly lines

across the holy ground

To help my brothers fight. No wonder that line stood out to the Israelis. And no wonder Cohen quickly caught himself and began to step back. The backpedaling was certainly related to his understanding that whatever his personal allegiances in those weeks, as a poet he had to be bigger than the Israelis, and bigger than this war. If you asked him who his enemy was in those weeks, I think there’s a good chance he’d simply say—inhumanity.

The change may well be linked to a specific moment in the war that seems to have been a breaking point. This is how he described it in his manuscript:

Helicopter lands. In the great wind soldiers rush to unload it. It is filled with wounded men. I see their bandages and I stop myself from crying. These are young Jews dying. Then someone tells me that these are Egyptian wounded. My relief amazes me. I hate this. I hate my relief. This cannot be forgiven. This is blood on your hands.

His tribal identification had gone too far. In the notebook you see that soon after writing that verse of “Lover Lover Lover,” he was already having second thoughts. The words “to help my brothers fight” are crossed out and replaced with, “to watch the children fight.” Now he’s an observer looking from the side, maybe even looking down. But that must not have sounded right either, and when the song was released a few months later the entire verse was gone. Later, when Cohen performed “Lover Lover Lover,” he’d acknowledge where he wrote it, but say it was for soldiers “on both sides.” By the time three years had passed, at a concert in France in 1976, he claimed to have written the song for “the Egyptians and the Israelis,” in that order.

In those years, with the American army still in Vietnam, most popular artists weren’t going to play for troops, because it might seem they approved of war. You needed to be sophisticated enough to see through the politics to the humanity of the soldiers. Johnny Cash and his wife, June Carter, went to Vietnam in 1969, spending a few weeks at an air base called Long Binh, singing for men heading into the bush and for the ones coming back on the medevac helicopters. “I almost couldn’t stand it,” Cash wrote, but he went. And James Brown went out with a few bandmates in 1968, despite the unpopularity of the war and despite the racial hatred that threatened Brown and America itself; the tour began just after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. He told the story in interviews with The Washington Post and Jet, and might have been speaking for Cohen as well.

Brown first played the airfield at Tan Son Nhut, near Saigon, then toured for 16 days, two shows at every stop, rehydrating between gigs with an IV drip. He claimed that even the Viet Cong snuck up to hear the music. “We didn’t do like Bob Hope,” Brown said. “We went back there where the lizards wore guns! We went back there where the Apocalypse Now stuff was going on.” Lots of people didn’t like the war. “Well, I don’t like the war, either,” he said, “but we have soul brothers over there.”

Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai was published on April 5 by Spiegel & Grau.

Matti Friedman is a Tablet columnist and the author, most recently, of Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.