The Jewish-born Triestine businessman Ettore Schmitz worked for his father-in-law’s paint company. When he felt the need to perfect his English, he arranged for lessons with an Irishman living in Trieste who earned his living as an English-language tutor. Schmitz met this tutor, James Joyce, in 1907 and studied with him for several years. During their acquaintance, which went beyond the bounds of mere student-teacher relations, Joyce worked on a novel that would appear in 1922 and whose action transpired over the course of a single day, June 16: Ulysses.

One of the two main characters of the novel is Leopold Bloom, an advertising salesman who feels remorse for his total abandonment of Judaism, which he had never practiced in any case. Leopold’s father, a Hungarian immigrant, had converted from Judaism to Protestantism before his son’s birth, and had married an Irish Protestant woman. Leopold, who had been thrice baptized, had himself converted to Catholicism to marry Molly Tweedy, who had been raised Catholic but was Jewish according to Halacha, her mother being a Jew from Gibraltar.

Joyce chose to have the non-Jewish Leopold viewed by all around him as a Jew and to have Leopold feel that identity, making the celebration of Bloomday a must in some Irish and Jewish literary circles. While fully attuned to Irish customs and habits, Joyce required assistance in matters Jewish, and it was his English student Schmitz who provided him with background information on the religion and mores of the Jews.

But that was not all. According to Joyce’s biographer, Richard Ellman, Schmitz was an important inspiration for the character of Leopold Bloom: According to Ellman, both men had mustaches, Catholic wives, and a daughter. More importantly, and unnoted by Ellman, is the conversion to Catholicism of both the fictional character and the Italian businessman, as well as the decidedly unliterary and unromantic fields in which they labored. So if Ellman is right, the celebrations of Ulysses’ centennial and Bloomsday this year owe a nod to the Italian Jewish businessman Schmitz.

Yet it was not only Schmitz who assisted Joyce in his writings; Schmitz also had literary aspirations, which Joyce enthusiastically supported. In 1892, under the name Italo Svevo—Italo-Swabian, a description of Schmitz’s national background, since he had a German father and Italian mother—he had self-published a novel, Una Vita, followed in 1898 by Senilità.

Both novels are important works and are still in print, but after their publication Schmitz took a lengthy break from writing. It was only in 1919, during his acquaintance with Joyce, that SchmitzSvevo set out to write his boldest work, Zeno’s Conscience. This novel of one man’s struggle with moral weakness, indolence, and illness through analysis, both psycho- and self-, appealed greatly to Joyce, as had Schmitz’s first two works of fiction: In fact, the most common English title of Senilità—As a Man Grows Older—was suggested by the Irishman.

Joyce encouraged Svevo in the writing of what would be his masterpiece. Once Svevo’s book appeared in Italian, Joyce saw to it that it was translated into French by Valéry Larbaud, who was also the translator of Ulysses, and he promoted the book tirelessly. Svevo was at work on a follow-up to Zeno’s Conscience when he was killed in 1928 in an automobile accident. This follow-up, A Very Old Man, appearing in a new translation by Frederika Randall published by NYRB Classics, is an essential addition to Svevo’s oeuvre, and allows us to see, not only how the character of Zeno would have developed, but also provides an occasion to examine Svevo in relation to one of the then-central ideas of his time, aside from Joycean literary modernism: Freudian psychoanalysis.

Zeno’s Conscience is not only the tale of a man’s life: It is a critique of psychoanalysis. The book itself, we are told in its preamble, was written at the suggestion of Zeno Cosini’s analyst, and it is the analyst who gets the first word. Dr. S. explains the origins of the book, and also the reason it was being published: “revenge.” writing of the novel was suggested to Zeno in the hope that “the autobiography would serve as a useful prelude to [Zeno’s] analysis.” Right from the book’s opening pages we are made to see that everything about it is intended to demolish psychoanalysis.

In return, Dr. S. is publishing his patient’s memories “in revenge, and I hope he is displeased.” Here, the greed of psychoanalysts is laid bare: The doctor is “prepared to share with him the lavish profits I expect to make from this publication.” There is, however, a condition placed on this profit-sharing: Zeno will be able to make money off the book he has written “on condition that he resume his treatment.”

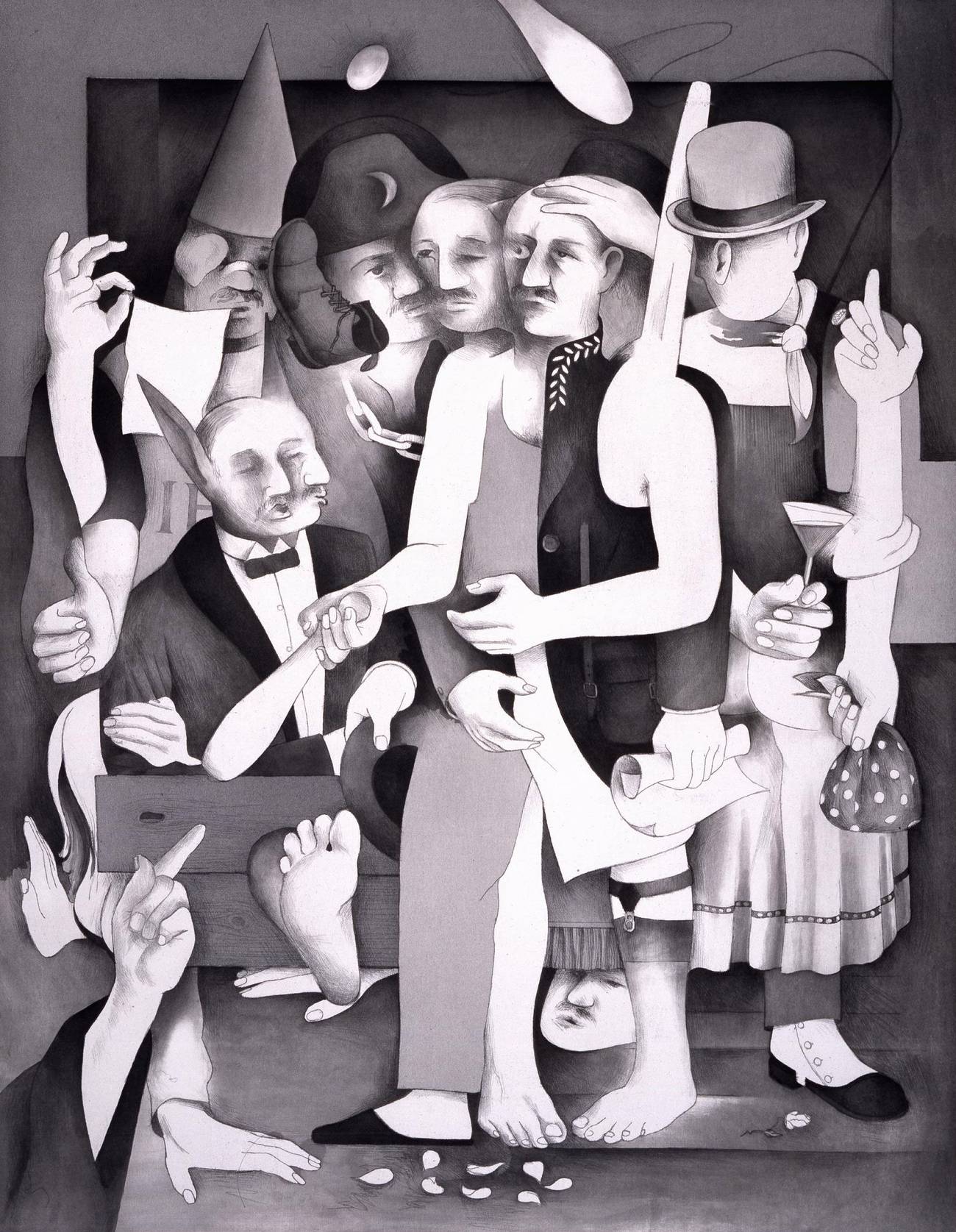

Italo SvevoPictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

It’s not inaccurate to see Zeno’s Conscience, then, as a precursor to, of all books, Portnoy’s Complaint. In both cases, it is without the assistance of the psychoanalyst that the title character confronts his issues. In Svevo’s book the punchline that ends Portnoy’s Complaint is placed at the beginning: The story of the patient’s life and struggles against his weaknesses is told before the analysis even begins.

Zeno’s issues are many, and if they are not handled in the form of Jewish humor as Portnoy’s are, Zeno’s self-analysis is every bit as uncompromising, both toward himself and those around him, not least his wife and children. What is lacking from Zeno’s Conscience is any hint of Jewishness. Zeno and everyone around him is Catholic. Religion is not central to either of the Zeno books, and there is no hint of rebellion against religion. But Mikkel Borch-Jakobsen, in his brilliant investigation of the background of those who stretched out on Freud’s couch, Freud’s Patients: A Book of Lives, makes an interesting suggestion on this matter.

The first of Zeno’s weaknesses is his inability to stop smoking. He has the willpower to say he will cast cigarettes aside, but lacks the willpower to actually do so. His life is a series of dates upon which he smoked on what he each time called his “last cigarette.” The businessman Schmitz’s relationship to cigarettes was tainted by the prohibition, reported by a member of Svevo’s wife’s family in his memoirs, against smoking at the paint factory he helped manage. Borch-Jakobsen proposes that “smoking represented for Svevo the muffled resistance of the Jewish writer toward the world of work and bourgeois-Catholic respectability, just as it constituted for Zeno major “resistance to his psychoanalytic healing and normalization.”

Throughout the two Zeno volumes, Zeno, simply through his rigorous self-analysis, accomplishes what is perhaps the most important thing that any kind of analysis can accomplish: unillusioned self-awareness. In the preparatory notes for analysis that are Zeno’s Conscience, the title character says that “Now that I am analyzing myself” he suspects that his love for cigarettes, and thus his inability to set them aside, was due to the fact that “they enabled me to blame them for my clumsiness.”

Cigarettes are not only a convenient scapegoat for his failure to be all he might have been, however; his insight is far deeper than that. “If I had stopped smoking would I have become the strong, ideal man I expected to be? Perhaps it was this suspicion that bound me to my habit, for it is comfortable to live in the belief that you are great, though your greatness is latent.”

Cigarettes are only one of Zeno’s many weaknesses. Women, more precisely the possession of a multitude of women, is a desire he is powerless to defeat. Zeno predicts that though only 57 he knows what his final moments will be. He says that “if I don’t stop smoking or if psychoanalysis doesn’t cure me, my last glance from my deathbed will express my desire for my nurse, provided she is not my wife, and provided my wife has allowed the nurse to be beautiful.”

Zeno hides nothing from himself. His story of his marriage reveals that his wife was one of four sisters, three of marriageable age. His wife was the least attractive of them all and was, in fact, unattractive. He had even gone so far as to propose marriage to the other two sisters and been rejected by them. Becoming aware of the remaining sister’s interest in him, he had married her. For Zeno, the path of least resistance is always the one to take. But he blames no one else for this tendency. His strained relations with his father, whose final gesture before dying was what might have been a slap administered to Zeno, and his distaste for children in general and his own children in particular: he admits to and accepts them all.

Taken together, Zeno’s Conscience and A Very Old Man are a chronicle of a life lived reflectively and honestly, even in its dishonest moments. Zeno hides nothing from himself and us, not doing so in order to excuse himself, but to explain himself to himself. Zeno complains that his analyst warned him that “during my therapy I was to reflect only when I was with him because unsupervised reflection would reinforce the brakes that inhibit my sincerity.” Following these orders resulted in his finding himself “unbalanced and sicker than ever.” It is writing and writing alone that has had a curative effect, for “it is only through writing, I believe I will purge myself of the sickness more easily than through my therapy.”

Zeno knows that he suffers still from his weaknesses at the end of Zeno’s Conscience and they will carry over to A Very Old Man. He has been told by his analyst that he “was cured, [and] I believed him completely and, on the contrary, I didn’t believe in my pains, which still afflicted me.”

Writing Zeno’s Conscience and A Very Old Man was as close as Svevo himself came to psychoanalysis, though he did attempt an Italian translation of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. Psychoanalysis was still a young art during Svevo’s lifetime, not yet subjected to the many attacks that have been made against it in our time. The Zeno books are essays in self-analysis and rejections of psychoanalysis. What was the source of Svevo’s animus toward psychoanalysis?

The tension between literary art and psychoanalysis is one source. But there were others. Svevo learned of Freudianism from a fellow Triestine Jew, Edoardo Weiss, who would later found the Italian Psychoanalytic Society, and whose older and younger sisters underwent analysis with Freud. In 1911 Svevo met Wilhelm Stekel, an early Freud disciple, at the resort of Bad Ischl. Svevo, who knew German, also read Freud’s works. So well before writing Zeno’s Conscience and A Very Old Man he was quite familiar with psychoanalysis.

But there was an even more direct connection between Svevo and Freud: His wife’s brother, Bruno Veneziani was a patient of the Viennese doctor. According to Borch-Jakobsen in Freud’s Patients, Veneziani, a young man whose family hoped he would enter their business, “was unable to carry anything out, for lack of will. He was idle and abulic, like Zeno.” Veneziani’s similarities to Zeno go further: He and Svevo swore a joint pact to quit smoking, the loser paying the other 130 Austrian crowns, a pact repeated in Zeno’s Conscience by the title character and his financial adviser, Olivi.

Veneziani was one of Freud’s many cases of failed analysis, the relationship between patient and analyst growing so strained that Freud would claim that his patient made antisemitic remarks to him. Freud terminated the analysis, having written to Edoardo Weiss that Veneziani “is a bad case, one particularly not suitable for free analysis [that is without institutionalization].”

Veneziani did ultimately spend time in a sanitarium, accompanied upon admission by Svevo, but the treatment accomplished little. He was sent for treatment because of his preference for idleness, his homosexuality, and his drug addiction. No attempted treatment for these conditions worked. Freud could just as well have been speaking of the fictional Zeno Cosini when he said of Veneziani that “I can heal those who seek healing, not those who refuse it.”

Svevo’s disenchantment with psychoanalysis nourished his masterpiece and its title character just like Joyce did, and just as Ettore Schmitz nourished Joyce’s construction of the character of Leopold Bloom, establishing a kind of serpentine link between Joyce and Freud running through the creator of Zeno. What does this connection tell us? As is recounted in Freud’s Patients: “As Svevo told [a friend], psychoanalysis is good material for the novelist, not a good way to heal: ‘From a literary standpoint [Svevo’s emphasis], Freud is certainly much more interesting. I wish I had had treatment with him. My novel would surely have benefited from it; it would have been more complete.”