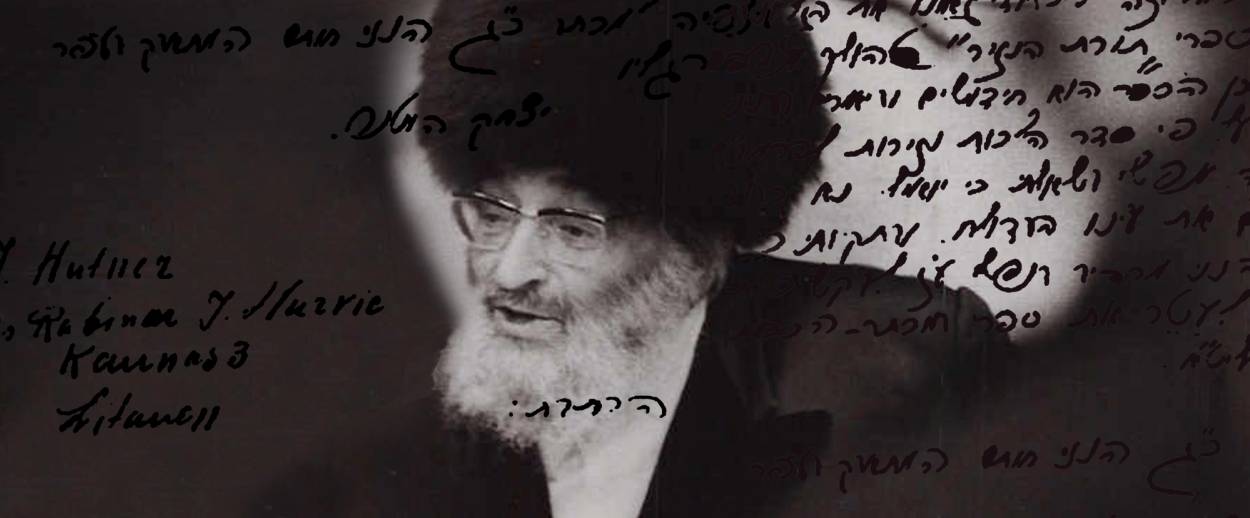

Letters of Love and Rebuke From Rav Yitzchok Hutner

To truly know a rabbinical scholar, read his correspondence

Perhaps the best biography of Rav Yitzchok Hutner, Hillel Goldberg’s 1989 book, Between Berlin and Slabodka: Jewish Transition Figures From Eastern Europe, begins its discussion by quoting a warning that every student of Rav Hutner, if given the chance to write a biography, would write something different. This quote is followed by another quote from a student that nothing quoted in Rav Hutner’s name should ever be believed.

The first story I heard of Rav Yitzchok Hutner took place on a hijacked plane. The Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin in Brooklyn was returning to New York, when the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a terrorist organization, hijacked the flight. The leader of the hijackers, realizing the esteemed rabbinic stature of their passenger, brought Rav Hutner a Pepsi. Rav Hutner, however, was not pleased. As recounted in David Raab’s eyewitness account in Terror in Black September, Rav Hutner responded that “he preferred his drink cold.” Hearing this story, I always found it striking that Rav Yitzchok Hutner’s dignity allowed him to insist on a cold Pepsi even in the face of terror.

Rav Hutner’s theology and philosophy were examined in Tablet magazine by his esteemed student and my teacher, Professor Yaakov Elman. The following, however, is not an examination of his thought as much as a consideration of his personality as reflected in his correspondence—a generally neglected area of rabbinic literature that can show the intimate, and oftentimes playful, side of rabbinic thought.

The letters of Rav Hutner were first published in 1981 with the title Pachad Yitzchok: Iggros U’Kesavim (Letters and Writings). There are 275 letters, though the final 10 were included only in later printings. The letters are divided into four sections: correspondence that is primarily related to Torah scholarship, collected essays, education and guidance, and, by far the largest section, personal matters. The volume is prefaced with an introduction from his son-in-law, Rabbi Yonason David, current Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Pachad Yitzchok in Jerusalem, which was originally established by Rav Hutner in the 1970s. Rabbi David rightfully notes that during Rav Hutner’s lifetime he insisted that his published works were only for those who had been present when the ideas were originally presented, so surely Rav Hutner would object to someone developing a relationship through his letters. But, since his passing, we are left with no other recourse.

***

One of the most revealing letters Rav Hutner wrote is also, by far, the shortest. Aside from the date and opening to the correspondent, it is one line. It reads, “With this, I hereby fulfill my responsibility and announce to you that I still do not forgive you.” This letter (#91) demonstrates an important theme, rarely seen so decidedly in a rabbinic work, namely the rebuke of the student, who, in this instance, did not join the yeshiva for the High Holidays. Unlike more commonly seen rabbinic rebukes, which are normally directed at antagonists to traditional Judaism, Rav Hutner saves his invective for his own students—a telling sign of the esteem in which Rav Hutner held the Rebbe-talmid (teacher-student) relationship. As Rabbi David notes in the aforementioned preface, rebuke is a theme throughout the work and should be seen as a reflection of the investment and esteem one must place in his teacher. Of course, Rav Hutner’s predilection for honest reprimand did not impede his ability to say, “I am sorry.” In letter No. 182, Rav Hutner, quite emotionally, apologizes for having jumped to the wrong conclusion. The letter is signed, “With a broken heart.”

The importance of dignity and esteem recurs throughout his letters. Many letters are either apologies by Rav Hutner for not having given enough or reprimands for having not received enough. But it was not only his own esteem, either given or received, that concerned him. In another letter (No. 125) he reprimands someone for describing a rabbi as having been “seized by anger.” Such a description, writes Rav Hutner, is not befitting a Jewish leader. Rabbinic leaders are not “seized” by emotion; rather, the righteous are in command of their passion. To be clear, it doesn’t seem that it was the display of anger with which Rav Hutner took issue, but the description of how the anger was manifest. Indeed, emotions of all sorts were a part of Rav Hutner’s rich experiential pallet, but esteem and dignity have a special ability to connect Jewish laymen with Jewish leaders. As Rav Hutner points out (No. 132) the act of according esteem itself demands esteem—thus transforming those dispensing of honor into the honoree.

Rav Hutner understood the gravity of a letter of reprimand. In another letter (No. 130) he explains why he took so long to respond:

I was not disposed to the characteristic of haste in regards to this letter; in fact, your last letter sat with me for far longer than my response required. For this letter is one of rebuke, and I understand the difficulty in writing words of reprimand. … Nonetheless, open rebuke comes from a hidden love (see Proverbs 27:5). But ultimately, such love is hidden only to be manifest through judgment. And certainly the heart does not desire that the judgment of rebuke should “remain for many days” (based on description of the lasting effect of writing in Jeremiah 34:14). And this is the unique difficulty that I feel when writing letters of rebuke. But ultimately, what am I to do? Is not the withholding of rebuke also a difficult judgment? Overcoming this apprehension required me to wait some time, hence the lack of promptness in my response. And it should be his will that the “open rebuke” should completely be substituted and consequently the light of my “hidden love” should be revealed.

The capacity for rebuke and reprimand was the sign of a healthy and strong relationship. “Your precious letter fittingly arrived,” he writes (No. 140). “And I am precise with my words and specifically use the phrase ‘precious,’ since all words of rebuke which depart from a faithful heart, are extremely precious to me.”

***

Love and rebuke were inextricably linked to each other in Rav Hutner’s letters. To one student, who had begun a project learning the works of the Maharal on the theme of rebuke, he wrote (No. 137), “If you entered my office now I would jump from my chair and run to greet you with hugs and kisses of endearment.” He was vigilant about esteem, but also esteemed in his capacity for appreciation and empathy.

Throughout his letters, moving displays of consolation and complement can be found. In letter No. 252, he closes, “My heart is broken in pieces. I ask of you, please give one shard of the broken fragments to the spirit of the bereaved mother.”

Underlying much of Rav Hutner’s compliments and correspondence is the magnitude with which he approaches appreciation. Appreciation—of his friends, teachers, mentors, whomever—is not discretionary, but obligatory. This theme appears quite frequently in his writing because, according to Rav Hutner, it was a feeling that specifically lent itself to the medium of letters. As he poetically writes (in the original Hebrew, the following lines all rhyme):

The spoken word said through the lips dissipates like froth above the water. While a word etched in lead will stand permanently for safekeeping. So too, there are emotions which dissipate quickly, while other feelings remain permanently through time. It is easy to understand that for an emotion that will easily dissipate it is fine to express through the spoken word—which too will fly away like a bird. But an emotion which is created permanently in the heart must be protected on paper.

***

The medium of the letter was particularly important to Rav Hutner given the volatility of the modern world, which makes seeking advice and counsel all the more necessary to pursue but even more difficult to dispense. Rav Hutner illuminates his hesitation to give detailed guidance by drawing a distinction between travel by land versus travel by boat (No. 100). Traveling on land leaves a clear path in the ground for others behind you to see, but a boat leaves no clear lasting impression on the ocean surface. Explains Rav Hutner, nowadays our journey through life is more comparable to travel on a boat, rather than travel by land, making it nearly impossible to draw conclusions or direction based on other travelers’ path that could inform our own. This letter presents two important themes in Rav Hutner’s letters: The fierce individuality he instilled in each of his students and the rich analogies he employed to explain his points.

Regarding the former, Rav Hutner at times refused to give any advice at all, instead insisting that the supplicant should listen to his own desires (No. 135). “Surely, there is room to provide guidance on the scales of reason,” writes Rav Hutner, “but it is unfeasible to do such on the scales of desire.” This student is only given a blessing that he should discover his true motivation and will. Another student is denied guidance all together, after Rav Hutner recuses himself from the question (No. 107). After this student asks where to continue his studies, Rav Hutner responds that he is obviously biased that his studies should continue in his yeshiva, so he cannot respond because “personal bias and advice are mutually exclusive.”

Rav Hutner’s guidance, when it is offered, is couched in rich imagery and striking analogies. “Only after removing a pot from the fire,” explains Rav Hutner (No. 97), regarding the character of a student who has left yeshiva, “and the boiling recedes can you really discern how much water was in the vessel.” This concept recurs throughout his letters. The true mettle of a student is only forged following his departure from yeshiva.

In a similar vein, Rav Hutner explains that you can only detect the strength of a person’s grasp when you try to remove the object from the person’s hand (No. 112). He writes: “It is entirely possible to learn with diligence in yeshiva and nonetheless, based on that, you still cannot evince the person’s relationship with Torah.” A relationship is only proven after it is challenged. For this reason, Rav Hutner often reminds his students that his ideas may resonate only after they have departed from his presence. Cleverly marshaling the verse in Psalms (34:12), “Go my children, listen to me,” Rav Hutner explains (No. 155) that a remote relationship often establishes the imperative for attentiveness. Intimacy is forged through absence.

It is not just absence from the walls of yeshiva that is given significance—spiritual voids are also invested with the presence of spiritual meaning. In an oft-cited letter (No. 94), Rav Hutner offers a brilliant analogy to someone whose secular accomplishments feel like a hypocritical duality in an otherwise spiritual existence. Rav Hutner assures the questioner that nothing could be further from the truth:

Someone who rents a room in one house to live a residential life and another room in a hotel to live a transient life is certainly someone who lives a double life. But someone who has a home with more than one room has a broad life, not a double life.

Rav Hutner advocated for a broad life—with expansive unity—and he modeled it. He also understood that in the pursuit of breadth, some students may fall short. It was in the possibilities and realities of failure, in fact, that Rav Hutner’s letters shine most brilliantly. We may not know which tests are which, but certainly through the course of life, people will confront failures that were simply inevitable (see No. 9). The true test, according to Rav Hutner, is not one’s ability to avoid sin and failure, but developing an appropriate reaction and evaluation of the occurrence of sin.

Such assessment should not happen, writes Rav Hutner, during times of self-doubt and insecurity. Just as Jewish law prohibits judgment during the nighttime, our self-assessment should not occur during times of personal darkness (No. 96). Failure, when properly assessed and integrated, can be a fertile ground for personal and spiritual development.

Rav Hutner’s consoling approach to sin and failure is likely the most enduring perspective contained in the collection of his letters. Yeshiva and seminary students who may have never heard of Rav Hutner or seriously studied his writings have likely been shown or read portions of his 128th letter—his fundamental treatise on sin and failure. The letter, which begins by lamenting the hagiographic nature of rabbinic biographies, reminds a student that greatness does not emerge from the serenity of our good inclinations but from our struggles with our baser tendencies. The verse in Proverbs (24:16), “the righteous fall seven times and stand up” has been perennially misunderstood. It is not despite the fall that the righteous stand up—it is because of the fall that the righteous are able to stand confidently. Greatness does not emerge despite failure; it is a product of failure.

If the medium is, in fact, the message, the message of these missives is the integration of theological profundities in the clothes of personal correspondence: The personal and subjective are seamlessly woven together with the eternal and enduring. Throughout the collection of Rav Hutner’s letters, none of the recipients’ names are listed. Listing the intended destinations of these letters would certainly have increased their historical value, but their absence likely increases the feeling of contemporary relevance they convey. The names are missing because the modern reader is intended to be their enduring addressee.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Dovid Bashevkin is the Director of Education at NCSY and author of Sin·a·gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought. He is the founder of 18Forty, a media site exploring big Jewish questions. His Twitter feed is @DBashIdeas.