Life Inside the Camps

Dutch Jew David Koker’s extraordinary diary, a clear-eyed and sensitive account of life inside a concentration camp, is finally available in English

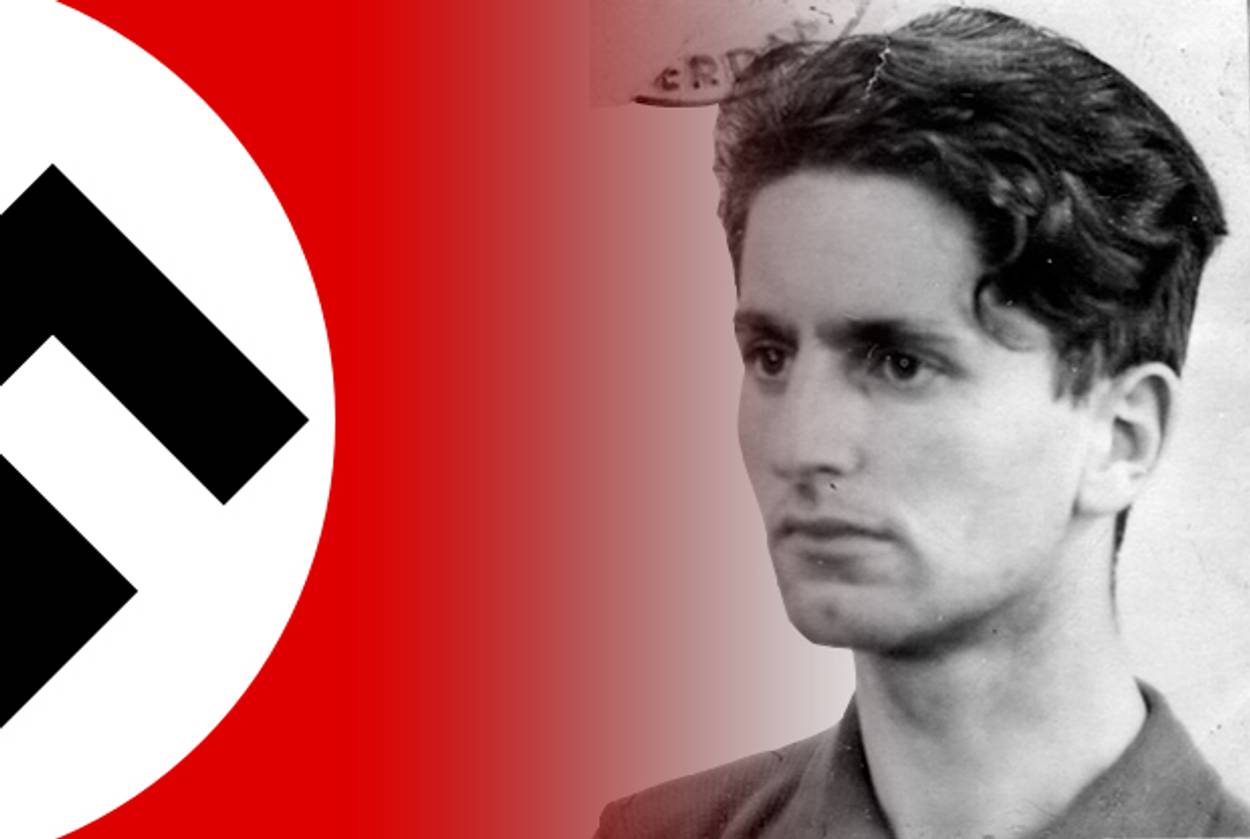

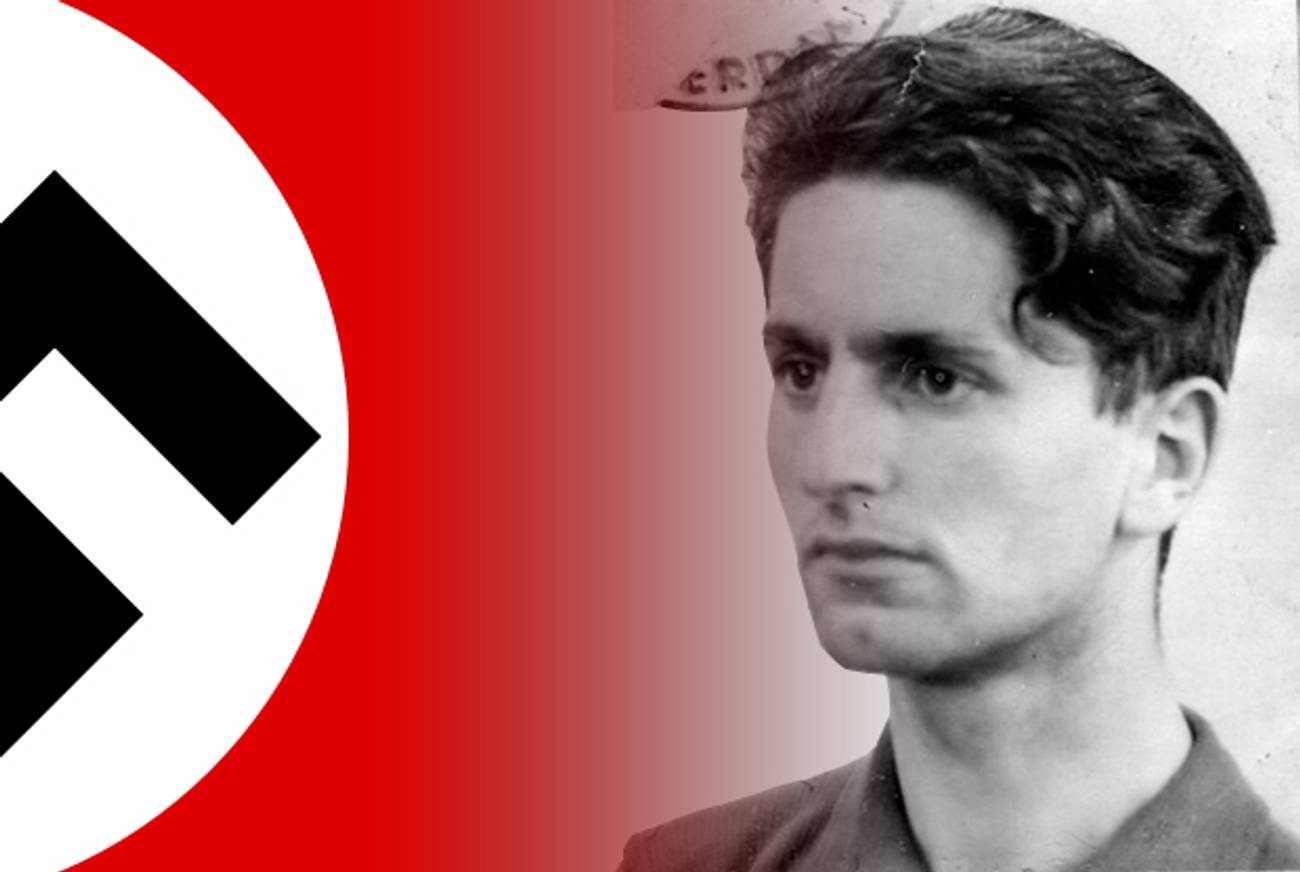

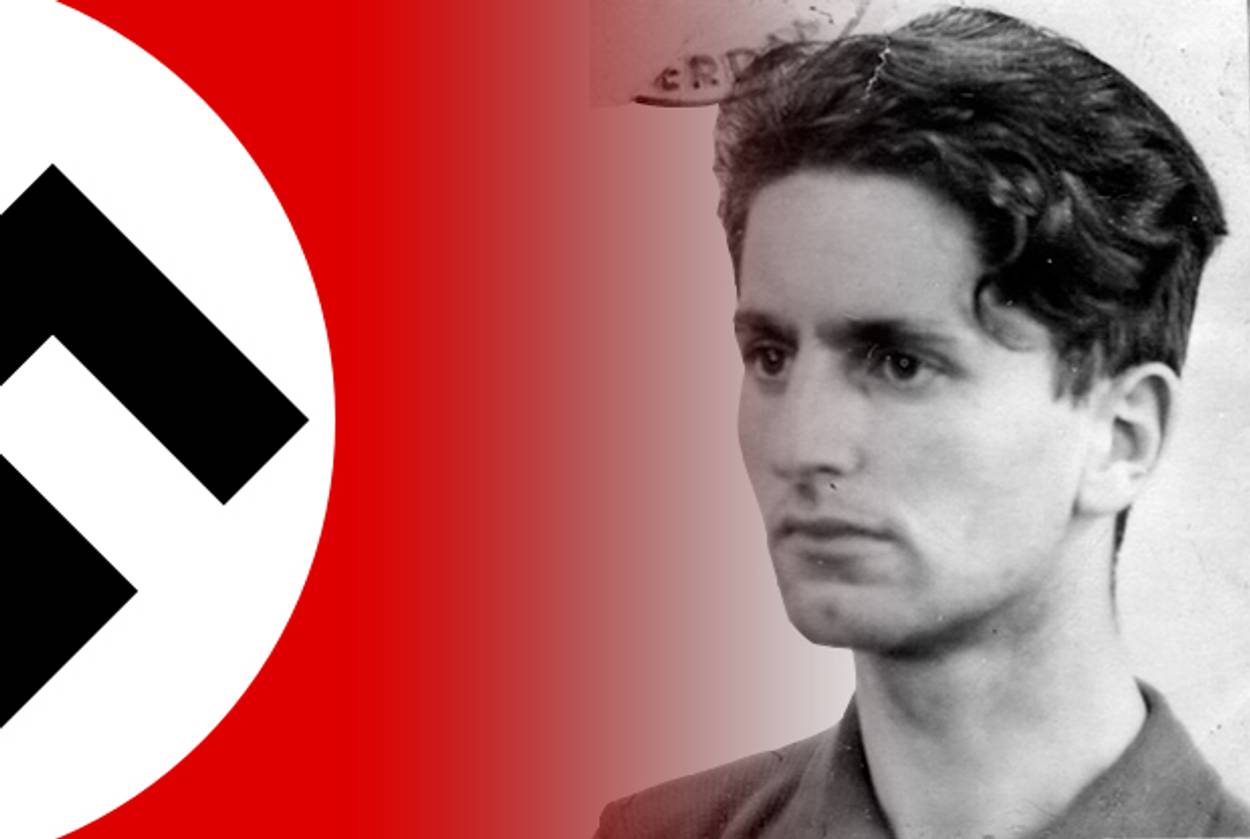

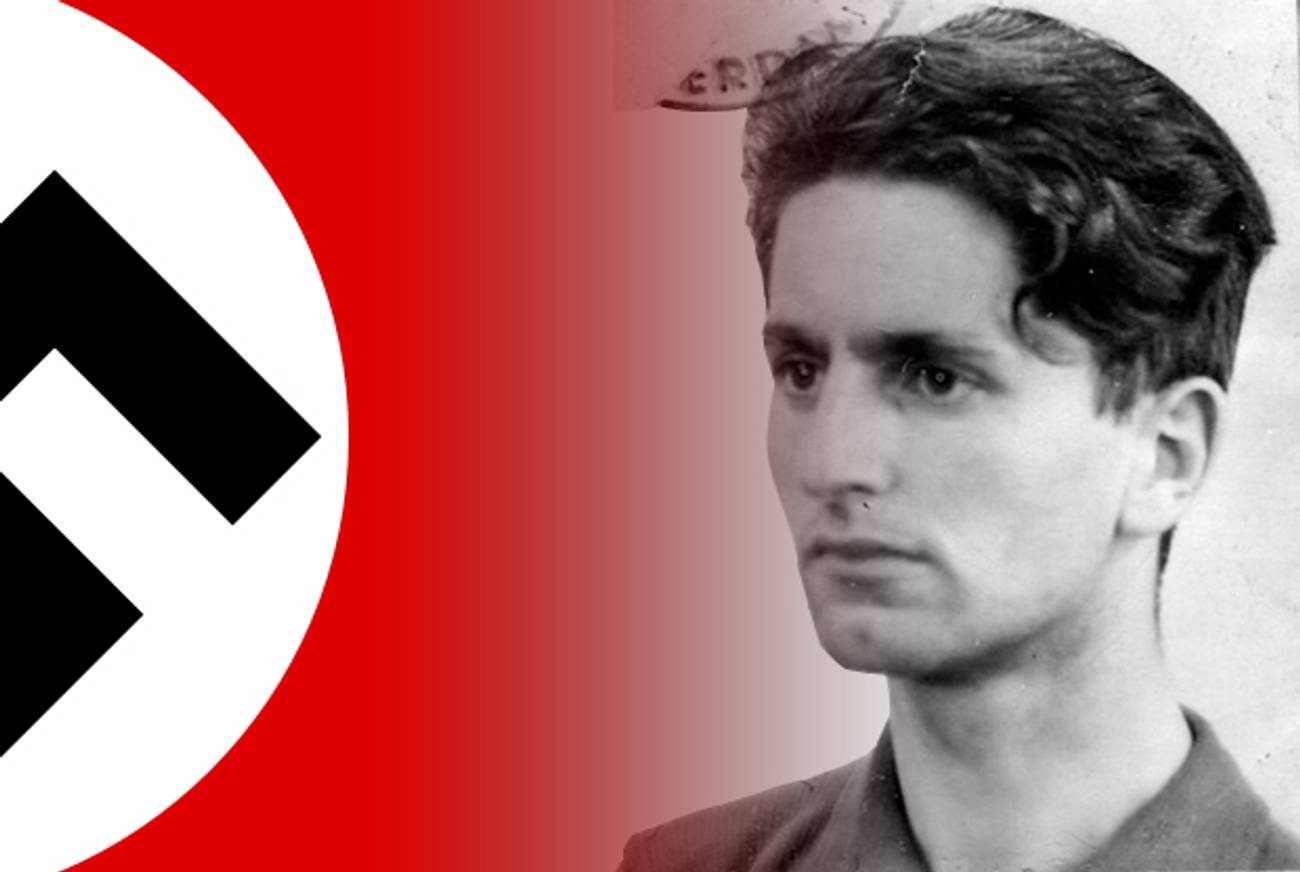

David Koker’s fate was in many ways no different from that of the nearly 6 million other Jews who died in the Holocaust. The eldest son of an Amsterdam jeweler, he was arrested by Dutch police in February 1943 and transported to Vught, a concentration camp built by the Nazis in the southern Netherlands. After being shuffled between other camps, he died on the way to Dachau in early 1945, where he was buried in a mass grave at the age of 23.

Before he died, however, Koker authored what may be the most extraordinary diary ever written inside a concentration camp. “In my opinion, it’s considerably more interesting than Anne Frank’s diary,” said Michiel Horn, a historian at Toronto’s York University and the book’s translator. At the Edge of the Abyss: A Concentration Camp Diary, 1943-1944, was first published in Dutch in 1977 as Diary Written in Vught. Despite immediately being recognized as a classic in the Netherlands, it has never seen publication in English, until now.

Part of what makes At the Edge of the Abyss so astonishing is that it survived at all. As the historian Robert Jan van Pelt writes in the book’s introduction, “While the number of postwar memoirs written by Holocaust survivors is enormous, and the number of diaries and notebooks written during the Holocaust by Jews while they were at home, or in a ghetto, or in hiding is substantial, the number of testimonies that were written in the inner circles of hell, in the German concentration camps, and that survived the war is small.” Those few that do exist are often fragmentary, and nearly all lack Koker’s extraordinary powers of observation and analysis.

Koker began his diary on Feb. 12, 1943, the day after he was arrested along with his parents and his younger brother. A published poet and budding intellectual at the time of his capture, he insisted on diarizing for nearly an entire year. As the teacher of the many children interned in Vught, he ingratiated himself with the chief camp clerk and his wife, which provided him with a relatively privileged position. In addition to keeping a diary, he was also able to write and receive letters, some of which are excerpted in the book.

In February of 1944, one of the civilian employees of a corporation that operated a workshop in Vught smuggled Koker’s diary out of the camp and gave it to his best friend, Karel van het Reve, who then gave it to David’s younger brother Max, who survived Auschwitz and received it upon his return to Amsterdam after the war. It was passed on to the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, where an employee transcribed it.

Max was reluctant to publish the diary for fear of its impact on his mother, who also survived Auschwitz but never emotionally recovered from the death of her husband and son. Still, David’s former high-school teacher, Prof. Jacob Presser, saw its value and quoted from it extensively in his history of the Holocaust in the Netherlands, published in 1965. Finally, Reve, who had become a famous Dutch intellectual by the mid-1960s, published the diary with just a few notes and an introduction.

Diary Written in Vught was instantly appraised as being of enormous value. “A single book can earn a writer a permanent place in literature, but to do that it has to be exceptional,” one critic wrote. “I do not think that, after reading the book, anyone will dispute that Diary Written in Vught fulfills that condition.” A popular Dutch public television show focused an episode on David, following Max, Karel, and others as they visited Vught, with readings from the diaries interspersed throughout. The book went through two printings within its first year of publication, appeared in magazine format for high-school students in 1985, and in an expanded edition with an epilogue by Max, in 1993. Determined to see an English translation of the book, Max approached a contact at the Anne Frank House, who put him in touch with Jan van Pelt, who in turn approached Northwestern University Press.

Three things mark At the Edge of the Abyss as an utterly distinctive and unique work of Holocaust literature that must be read now that an English-language translation exists. First, the insider account of a camp; second, Koker’s literary and analytic abilities; and third, the only first-person report of an encounter between a Jew and Heinrich Himmler, head Nazi and overseer of all the camps. On Feb. 4, 1944, Koker records that on the previous day he had looked directly at the man responsible for the Final Solution. The haunting entry reads as follows:

A slight, insignificant-looking little man, with a rather good-humored face. High peaked cap, mustache, and small spectacles. I think: If you wanted to trace back all the misery and horror to just one person, it would have to be him. Around him a lot of fellows with weary faces. Very big, heavily dressed men, they swerve along whichever way he turns, like a swarm of flies, changing places among themselves (they don’t stand still for a moment) and moving like a single whole. It makes a fatally alarming impression. They look everywhere without finding anything to focus on.

What makes this passage remarkable is not just the fact of the encounter but Koker’s careful, emotionally attuned attention to detail. Koker notices not just Himmler but the deference of his supplicants. He observes with nonchalance, as if he were encountering not a genocidal murderer—and the person who keeps Koker in a concentration camp—but an ordinary man on the street. As Presser put it in his review, “We are aware of no other camp documents that sound so subdued: a superficial reading may suggest that Koker did not see the horrors surrounding him, with a more attentive reading one discovers them all right, even if they are hinted at rather than described.”

In addition, Koker provides a glimpse of life in the camps rarely seen before. He reveals aspects of ordinary life that take place beneath the surface of uniforms and barbed wire. Koker had a girlfriend, Nettie, a German-Jewish refugee, who had been living in hiding in Amsterdam since 1943. But he also met a girl in Vught, Hannelore (Hannie) Hess, with whom he had a relationship. “I have a sweetheart here in the camp, whom I find extraordinarily attractive physically,” he writes in one entry. She is “a girl of 18 with the appearance of a 23-year-old.” He confesses that he cannot stop thinking about her:

I have the strength to be very open with her, about “personal” matters and about everything that inspires my thoughts and feelings. And she always knows exactly the right moment to give me the stimulus to keep on speaking, by means of some pleasant words, a sweet anticipatory or assenting gesture, or a friendly question. … In love with her? It’s because of that unknown, almost uncomprehending something that exists between us. That newness, not yet habitual. And also the wonderment each time we reveal something of ourselves to each other.

These words seem like they could have been written by a young lover in postwar Amsterdam, not in a concentration camp. They reveal humanity’s insistence on maintaining whatever normalcy and intimacy is possible in the most abnormal and isolated of settings.

Somehow, Koker also finds beauty inside the physical landscape of the camp. From one poem dated May 17, 1943: “The evening air so pure and intimate/ A sky that’s hazed in whiteness by the sun/ and trees with foliage in great profusion/ with glittering flecks of silver from the sun.” He is also occasionally magnificently insightful. Jan. 6, 1944: “The goal is neither happiness nor unhappiness. It’s the unfolding of human potential. The development of that piece of the universe that you represent, as it were, even when it happens at the expense of what people call the self and their own welfare. Actually, it always happens at their expense. By feeling a lot we expand the world.”

If there are lovely moments of affection and poetic sentiment in At the Edge of the Abyss, however, it is very far from a Life Is Beautiful-style attempt to put a positive spin on the worst of human depravity. “Unlike Anne Frank’s diary or Etty Hillesum’s letters, David’s diary is not a source of optimism or spirituality,” as van Pelt puts it. “Instead he mercilessly probes the abyss that opens around him and within himself.” The results often make for brutal reading. Koker can be tender, but he is also ambitious and cold. He is, however, always self-aware enough to recognize these traits in himself. From a May 3, 1943 entry: “You become selfish, even towards your own family. … Sometimes I treat the children with bitterness, yet the friendliest treatment hides a bit of sadism and lust for power. … I don’t feel bad when I deny them something or give them an order. A kind of feeling of being in charge.” Nov. 7, 1943: “Sometimes when I see the mass of people here, a strange thought passes through my head: we don’t deserve it [i.e., liberation]. Not true, because who deserves to be in a camp, but as an image it’s instructive.”

If any hope can be gleaned from At the Edge of the Abyss, it may come from the realization that intellectual life and critical judgment can be maintained under the most horrific of conditions. That, and the fact that David Koker’s gifts did not perish in a concentration camp but lived on after him. But perhaps the temptation to find solace in something as tragic as Koker’s death and as cataclysmic as the Holocaust should be resisted. One cannot imagine the phenomenal author of At the Edge of the Abyss embracing easy answers.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jordan Michael Smith is a contributing writer at Salon.

Jordan Michael Smith is a contributing writer at Salon.