Lincoln Kirstein at MoMA

The enigmatic, influential benefactor of the arts comes home to the temple of modernism he once shunned

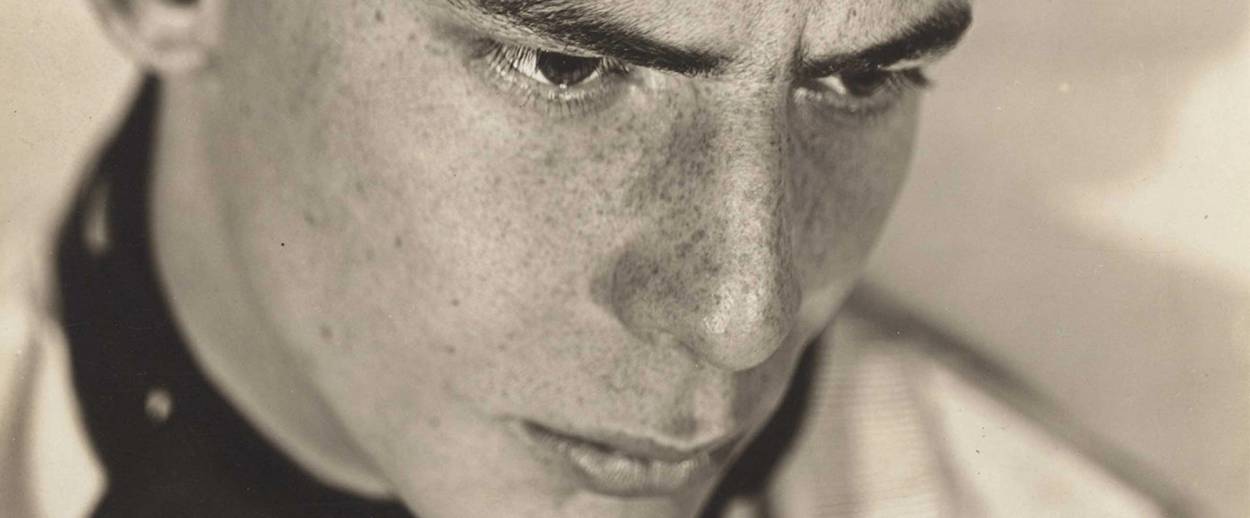

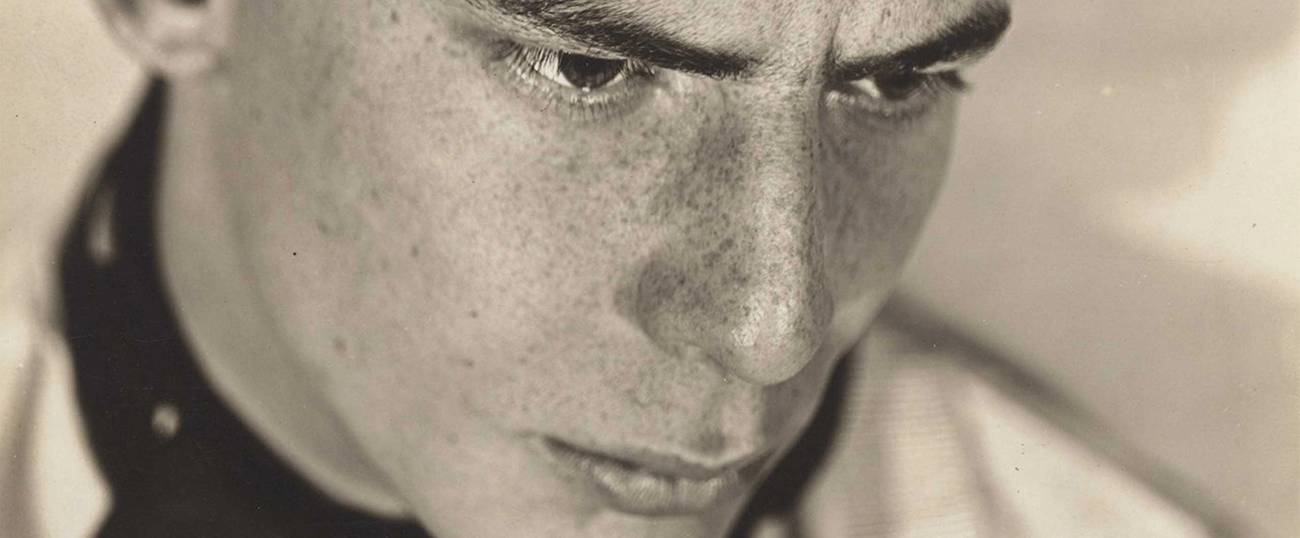

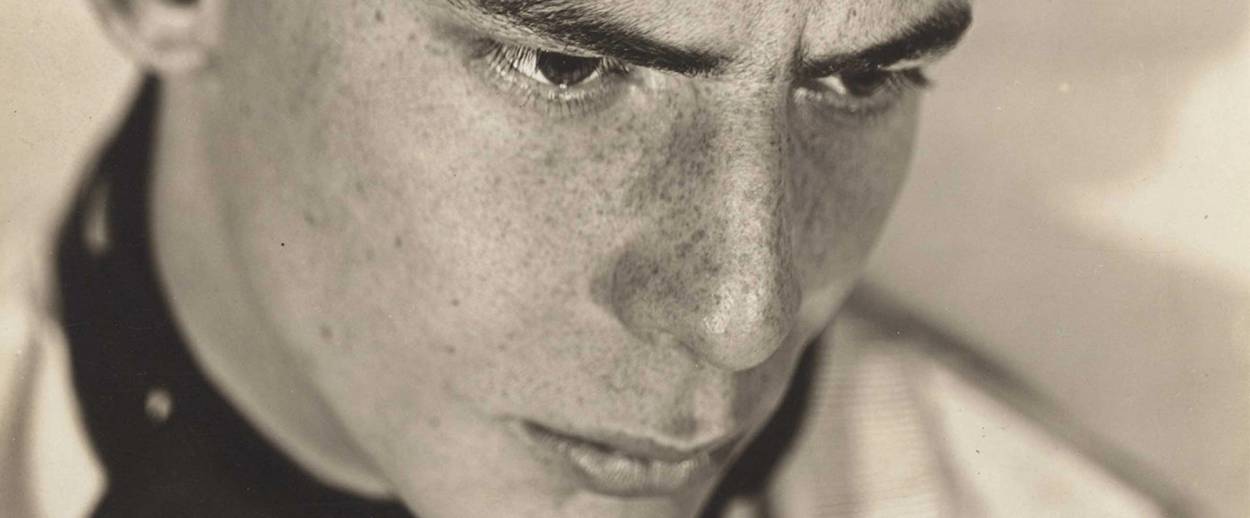

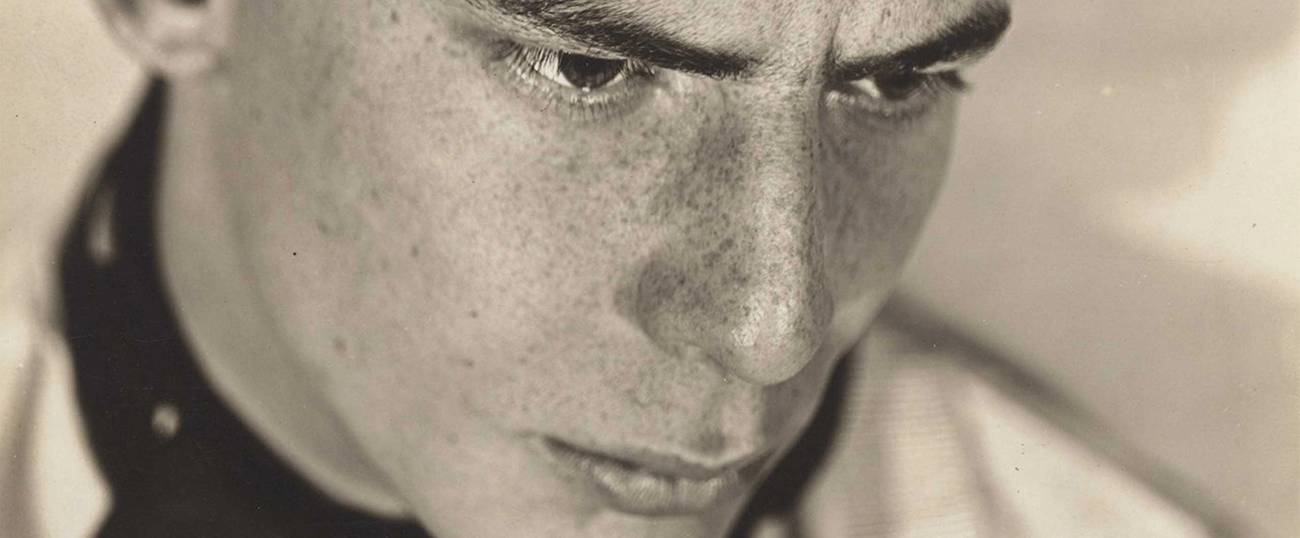

In a portrait photograph at the exhibition Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, which opens Friday at MoMA and runs through June 15, Walker Evans caught the youthful, undefended eyes of his subject. His head dropping forward, his clouded expression hovering between meditation and sullenness, Lincoln Kirstein was alone with his thoughts. It was 1931 and Kirstein was recently graduated from Harvard. With frontal light casting shadow against the bare wall and throwing shine along the width of his subject’s forehead, Evans looked down from above and across, allowing his lens to take in the complexities of texture: the slight fuzz of crewcut, luxuriant eyebrows, chapped lips, the imperfections of freckles and still-adolescent skin, the deep struggle that was just becoming evident in lines breaking above the brow. Years later, reflecting back on their early encounters, Evans remembered, “I could see he was a brilliant young man.”

For a while, the two were good friends. Close in age (Evans was four years older), both from elite backgrounds and both bisexual, they traveled in some of the same circles. But Evans was, as he put it, ascetic, “since I had a genteel upbringing [I thought] that real life was starvation.” Kirstein, on the other hand, was drawn to the bohemian world, its highs and lows, which included the dives and sailor bars where he could be reckless. He wrote in his diary about some close calls and unexpectedly rough encounters: “my mind is usually conscious of what the body is doing, even urging it away from … an interest in danger that amounts to insanity.” In another series of photographs Evans posed Kirstein as a gangster with a bowler hat and cigarette like James Cagney in Public Enemy, which had recently been in the movie theaters, and then, in a couple of mug shots, as a rogue. “Lincoln, you know he loves all sorts of funny business,” Evans would say later.

That year, Kirstein was often in New York. He’d meet Evans for meals, picking up the tab since he worried his friend didn’t have enough money to eat. In the spring, he invited Evans to join him and another friend, the Marxist poet John Brooks Wheelwright, on an expedition to observe and record 19th-century New England houses, many in disrepair; he wanted Evans to take the photographs. For five days they drove through Boston, Chestnut Hill, Salem, and Arlington; later they went down to Boston’s South End and up to Newbury Port. They were looking at Greek Revival and Gothic Revival structures as well as houses with mansard roofs and others from the Italian Villa School. As Kirstein wrote about it, these were examples of New England’s “building during its most fantastic, imaginative, and impermanent period.” In the process, he learned about the exactitude of photographic technique and the monotony of setup; Evans was passionate about shooting and insisted upon returning to various locations many times to get the right “hard and bright” light. For Evans, it was the beginning of a lifelong devotion to architecture and architectural styles, an essential component of the famous images of rural communities that he did for the Farm Security Administration. It also led to the 1933 show, Walker Evans: Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Victorian Houses, the first one-man photography exhibition at the nascent Museum of Modern Art.

But it was Kirstein who organized the project, donated the images to the museum, and wrote about Evans as “a surgeon operating on the fluid body of time.” The symbiotic relationship he developed with Evans, initiated by some grand ideas and fortified by the generosity of his patronage, included a willingness to work by his friend’s side “like a surgeon’s assistant.” It was a paradigm for many of Kirstein’s artistic undertakings, most notably his partnership with George Balanchine whom he brought to America that same year. Together Kirstein and Balanchine would become directors of the School of American Ballet and eventually the New York City Ballet. Their success was delicately balanced, dependent on Kirstein’s deference to Balanchine’s genius as a choreographer and his willingness to stand as support, looking after details, raising money, making sure the lights would turn on and the curtains would rise. “Don’t worry about anything, Lincoln,” Balanchine would write to Kirstein nearly 20 years later. “Everything is all right.”

***

Lincoln Kirstein died in 1996 but his centenary was celebrated in 2007 with exhibits and events at many institutions where he had an affectionate bond: the Whitney, the Met (during his lifetime, he gave them more than 1,000 works from his private collection), the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (the recipient of his enormous private collection of dance materials that were at one time housed at Harvard and MoMA), the New York City Ballet, the Wadsworth Atheneum, and the Harvard Theatre Collection. Kirstein gave to American arts organizations the way a generous parent gives to a child. At the end of his life, he arranged for Jerry Thompson to photograph the arrangement of objects in his house for the book Quarry. The text, which Kirstein wrote, served as a way to say goodbye to the material world, the thousands of things he had collected and treasured, and to explain their connection to the life he lived. Like many of Kirstein’s projects, this involved synergy, since he planned for the book to be used as publicity for the auction of what was essentially all his worldly goods, the proceeds going to the endowment of the School of American Ballet.

During the centenary year, Peter Kayafas at the Eakins Press updated Lincoln Kirstein: A Bibliography of Published Writings with 575 entries of books, articles, plays, ballet libretti, catalogues, and program notes. Martin Duberman published a well-received and useful biography, The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein; and the dance historian Nancy Reynolds, who performed in the New York City Ballet and worked with him on Movement & Metaphor: Four Centuries of Ballet, edited a charming anthology, Remembering Lincoln in which he was variously recalled by friends and acquaintances as a bear (he was 6-foot-3), a fox, a New England seafaring prophet, a ghost, a shadow, an enigma, a tempest, a facilitator, a Cheshire cat, a giant, an eagle, and an “almost child-like man who occasionally came out for friends.”

In essence, there were two Lincoln Kirsteins. When things were going well, his abundant vitality resulted in marvelous projects. It’s been said that Kirstein invented the field of dance history, publishing his first three books on the subject in three years when he was still in his 20s: Najinsky, an anonymous collaboration with Romola Nijinsky, in 1933; Fokine, in 1934; and Dance: A Short History of Classic Theatrical Dancing, in 1935. Decade after decade, he was still going, with his interests spoking out in unpredictable directions. At the age of 82, he published Memorial to a Marriage, a profound reflection on the story of Saint-Gaudens’ statue of Marian (Clover) Hooper Adams commissioned by her husband Henry Adams and situated in D.C.’s Rock Creek Cemetery. That same year, the film Glory, influenced by his earlier book Lay This Laurel, won two Academy Awards.

At other times Kirstein was afflicted by demons so fierce that his prose would snarl into the passive voice and entangle his long, 19th-century sentences beyond the rules of grammar. Ballet students and staff were on alert if he showed up at the office wearing his old army jacket (what they referred to as his Boy Scout jacket) instead of his customary double-breasted black suit with tarnished brass buttons. There were occasions when he had to be hospitalized and constrained during full-blown episodes of manic-depression.

During much of his life, Kirstein was a social gadfly, beginning at Harvard where he had lovers of both sexes and a large community of friends, including Maurice Grosser and Virgil Thomson, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Agnes Mongan, Alfred Barr, and Everett (Chick) Austin, as well as a circle of Boston Brahmins whom he met through his sophomore year roommate Francis (Frank) Cabot Lowell. In New York, he came under the influence of Muriel Draper and her high bohemian though shabby salon where she hosted the charismatic mystic George Gurdjieff. But his community soon expanded to include a conglomeration ranging from E.E. Cummings to the gallery owner Julien Levy, and the crowd that was associated with MoMA like Philip Johnson, Eddie Warburg, and Nelson Rockefeller. In London, he became close to David Garnett, Lytton and Esther Strachey, John Maynard Keynes, E.M. Forster, and many others. Because of Hound and Horn, the literary magazine which he and Varian Fry started in 1927; the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, the gallery which he, Eddie Warburg, and John Walker founded in 1929; as well as the Junior Advisory Committee of the Museum of Modern Art, which he joined in 1930, the year after the museum was founded; he established himself while he was a very young man at the eye of the hurricane that was modernism. Paradoxically, his own interests—which ranged from Napoleonic furniture to West African masks, Abraham Lincoln memorabilia, and pussycat trinkets—was often far from modern.

None of this could have been possible without the wealth and connections of his forbearing parents with their origins in the Jewish community of Rochester, New York (the same community where Florine Stettheimer’s paternal grandparents settled and where she was born). His grandparents, who came to Rochester in the mid-19th century, read Goethe and Heine and, like other Reform Jews of their time, believed in deed over creed, considering themselves assimilated while their social lives existed within the boundaries of their large extended Jewish families and Jews of similar social status. Boys were circumcised on the eighth day (although, in Lincoln’s case this wasn’t done by a mohel but by the family doctor and the result was almost fatal when septicemia set in) and the men went to the synagogue on the Day of Atonement—his father called it “the day of at-one-ment.”

The grandfather on his mother’s side, benefiting from Civil War contracts for military uniforms, established the Stein-Bloch Company, one of the most successful men’s clothing manufacturers in the country. In the Gramercy Park townhouse where Lincoln Kirstein lived with his wife, Fidelma, he kept a memento from the Stein lakeside “cottage”: a gilt-bronze tree of life, commemorating a 50th anniversary, the bauble festooned with polished cabochons engraved with the names of seven children, his mother, Rose, being the youngest.

Louis Kirstein, Lincoln’s father, had a spotty start; among other things, he was said to have been a hobo and a janitor in a bordello in St. Louis. Eventually, he rose to become vice president and subsequently chief executive officer of Filene’s department store as well as president of the Boston Public Library. When he died, he was remembered as one of the most influential Jews in America, holding major positions in Jewish philanthropy, with ties to Felix Frankfurter, Mayor La Guardia, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, as well as the three presidents before him. Not only was Louis a significant benefactor to his son’s many projects, often bailing him out when he was in a jam, but he also provided him with a generous allowance so he didn’t need a steady job or income.

The process of individuation was a particularly gruesome ordeal for Lincoln Kirstein. The privileges of his wealth and education insulated him from the garden variety anti-Semitism his parents had worked around by staying within the confines of Jewish society (their society included Justice Louis Brandeis and Rabbi Stephen Wise). To that extent he had a free run and could choose what he called “low life,” or mix with artists, writers, or the superrich like Nelson Rockefeller. But there was the problem of how to face off against his father, a man who seemed to represent high social rectitude and achievement. How to strike out against someone who had indulged every stage of his development and been patient with extravagant stumbles (it took Lincoln three tries to pass the Harvard entrance exams) and infatuations (Louis and Rose thought Muriel Draper was “a menace”)? How should he put things together without joining the merchant class or one of the professions? Eventually, recognizing that he wasn’t going to make his way as a novelist (he published two novels), a dancer (he took lessons with Fokine), or a painter, he developed a variant model of his father’s entrepreneurship, charisma, and philanthropy, and made it his life’s work to build and support great cultural institutions.

To a certain extent, Kirstein had a charmed life, often finding himself inexplicably at the right place at the right time, starting with the accident of witnessing his original hero Diaghilev’s funeral cortège on the Grand Canal in Venice in 1929. During World War II, stationed outside of Washington, D.C., he was browsing at the Lowdermilk bookshop and came across the discarded leather-bound album containing Frances B. Johnston’s platinum prints of the Hampton Institute commissioned for the 1900 Paris Centennial Exposition (he donated it to MoMA in 1965). As part of the Arts and Monuments Commission, he and the architect Robert Posey were the first to discover and go into the salt mine at Altaussee near Salzburg. Together they unlocked the iron door of the compartment where Van Eyck’s panels of The Adoration of the Lamb lay on the floor. At other times, he had the thunderous energy to make things happen: When he needed to install two heroic-sized Elie Nadelman marble sculptures inside the newly built State Theater at Lincoln Center, he arranged for holes to be blasted into the just-finished theater walls.

***

Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern honors his contributions as an early benefactor, adviser, writer, buyer, and exhibition organizer. Kirstein, who wasn’t an artist but an artistic presence, makes an unusual subject for a show, but there’s a logic behind the project. Because the museum will shut for four months this summer before reopening in an enlarged and reconfigured space, it’s an appropriate time to take stock and look back to the earliest ideas for the institution and the idea of “modern.”

It’s customary to talk about modernism as a movement that necessitated a break with the past: Artists had come to the end of representation and replaced it with abstraction. But Kirstein had an alternative vision, insisting on a chain of continuity and, in fact, there’s a growing consensus today that’s on his side, reminding us of a large group of forgotten artists, often interested in the form of the human body, who worked during the modern period and have been overlooked. Kirstein was responsible for the 1932 show Murals by American Painters and Photographers and he had his hand in exhibits on Gaston Lachaise, two Walker Evans shows, Latin American Painting, American Battle Paintings, Elie Nadelman, American Realists and Magical Realists, as well as the Hampton Album. A rupture occurred when he published an explosive article, “The State of Modern Painting,” in Harper’s magazine, explicitly criticizing MoMA and Alfred Barr for what he thought of as a bias in favor of School of Paris artists. He was bewildered by the attention swirling around action painting and abstract expressionists.

The current exhibit includes portraits, paintings, sketches, and photographs of Kirstein and his circle, as well as works of art that were in the many shows he helped organize, donations he made to the museum, and a large group of paintings he bought on behalf of the museum in 1942 when he was traveling through Latin America while working on an intelligence mission for Nelson Rockefeller. From that collection, Antonio Berni’s powerfully vibrant New Chicago Athletic Club stands out and ought to be shown more often. One thread that runs through the exhibition as a whole is Kirstein’s love for craftsmanship, the artistry of the hand. You see this in the once-famous Pavel Tchelitchew’s layered and membranous “Nervous System,” part of his design for the ballet Cave of Sleep, and also in his enormous work “Hide and Seek,” a fantastically grotesque painting that, to my mind, is blessedly out of fashion today. After WWII, when figurative artists were overshadowed by abstract expressionists, Kirstein championed Gaston Lachaise and Elie Nadelman, represented here with polished bronze pieces that are equally classical as well as modern.

Possibly the best part of the Kirstein show is the large center room where you can see video excerpts from the early Ballet Caravan pieces like Billy the Kid and A Thousand Times Neigh. Paul Cadmus’ delightful designs stand out, especially the see-through overalls worn by the gas station attendant in Filling Station. Kirstein himself wrote the libretto for Filling Station. With music by Virgil Thomson, it was choreographed and performed by Lew Christensen playing the station attendant in 1938. When you watch it in the gallery, it’s hard to imagine a more American story with its truck drivers, state trooper, badly mannered family, rich girl, rich boy, and gangster with a gun. The burlesque, danced with delicacy and virtuosic high jinks, balances comedy and tragedy.

There’s a Flannery O’Connor undercurrent to the plot that raises questions about desire, terror, strangers, and accident. These were the themes that haunted Kirstein from earliest childhood, themes he tried to neutralize, in his way, with art, with the force of personality, and then vigorously and variously with atheism and religion. In a diary he kept from his boarding-school days he wrote with self-loathing: “in chapel I prayed, which shows what a sniveling little coward I am.” Later, he tried Gurdjieff’s philosophical dialect at the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at Fontainebleau. After considering Catholicism for decades, he was baptized as a Catholic when he was almost 80 years old and, for a while, even attended neighborhood Mass. Predictably, as he said about Judaism, it didn’t stick.

***

Read more of Frances Brent’s art criticism in Tablet magazine here.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.