Tracing the Rise of Abraham Cahan, From Factory Worker to Newsroom Titan

In an excerpt from Nextbook Press’s new biography, the founder of the ‘Jewish Daily Forward’ makes his way to New York

Abraham Cahan founded the Yiddish-language Jewish Daily Forward in 1897, and over the next 50 years turned it into a national newspaper that changed American politics and journalism, and earned the trust of millions of Jewish immigrants. He went on to write fiction as well, most notably the novel The Rise of David Levinsky. In a new biography of Cahan from which the following excerpt is taken, Seth Lipsky—founding editor of the English-language Forward—recounts Cahan’s personal life, political leanings, and achievements as a writer.

Abraham Cahan arrived in America on June 6, 1882, disembarking at Philadelphia, where the U.S. Constitution had been crafted only ninety-five years earlier. Some individuals who had been infants at the time when the political giants were creating America might still have been alive. Before long, however, they would be gone, and in a sense, America was at a historical tipping point. The Civil War had been over for only seventeen years, and the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution had been adopted shortly thereafter, to ensure that the southern states, furious over Reconstruction, would not deny the newly freed slaves their basic civil rights. Industrialization was well under way in cities throughout America, and the machines that were mass-producing men’s and women’s clothing created factory jobs for the thousands of immigrants arriving at America’s shores. Chester A. Arthur, who had become president in 1881 upon the assassination of James A. Garfield, would confound his corrupt political cronies two years later by establishing the landmark Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. Change was clearly in the air.

With astonishing speed, the ideas of socialism, Marxism, and social democracy—brought to America by European immigrants such as Cahan—would become part of the American political conversation and would revolutionize the relationship between laboring men and women and their employers. With equally surprising speed, Cahan, “greenhorn” though he was, became a part of the emerging reform movement and, through his journalism, rose to a position of unparalleled power and influence within it.

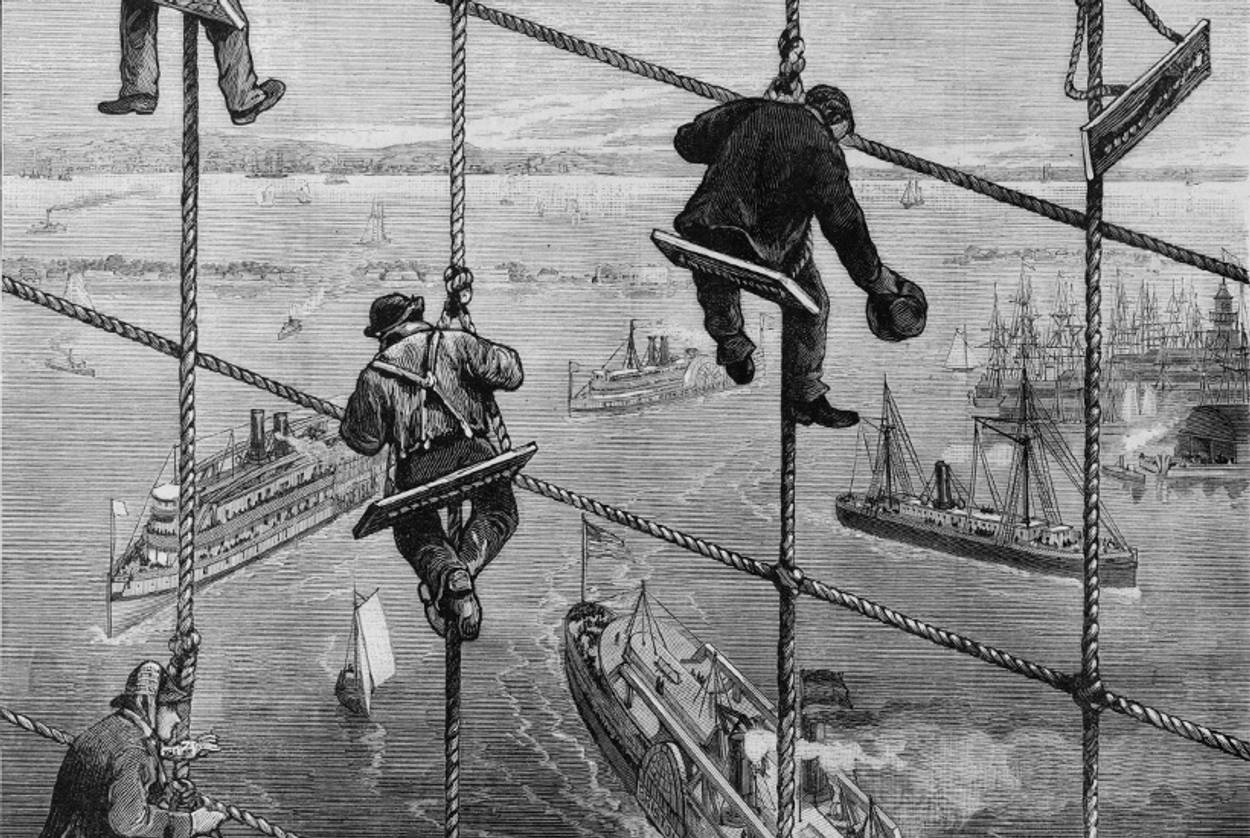

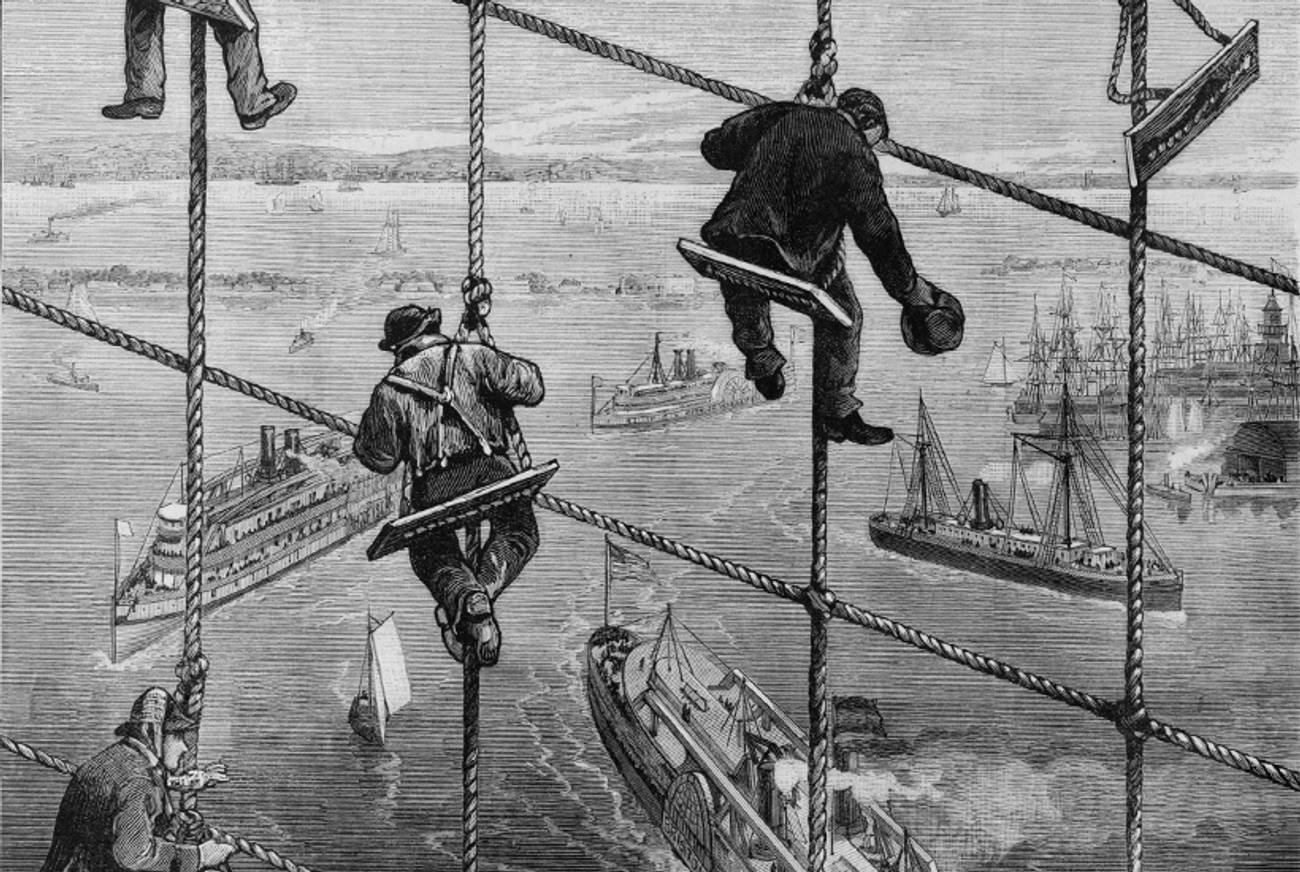

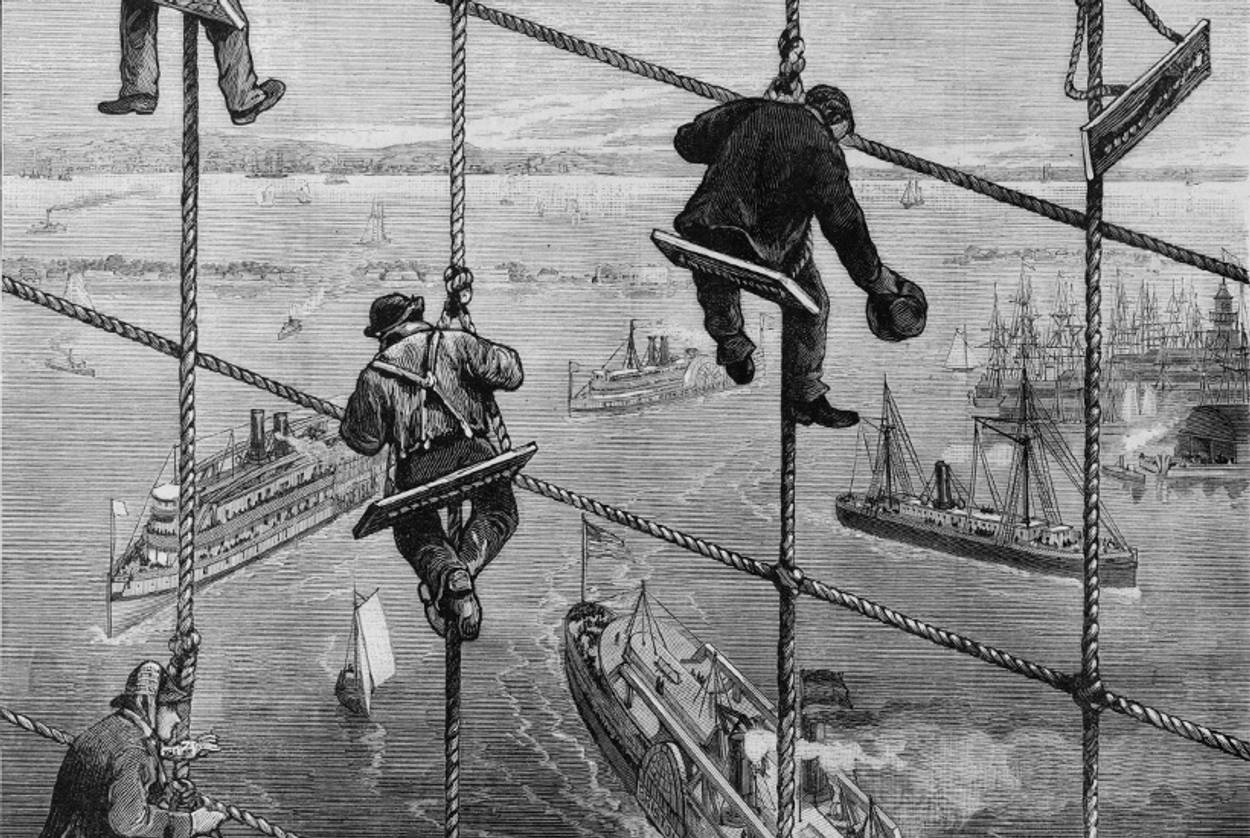

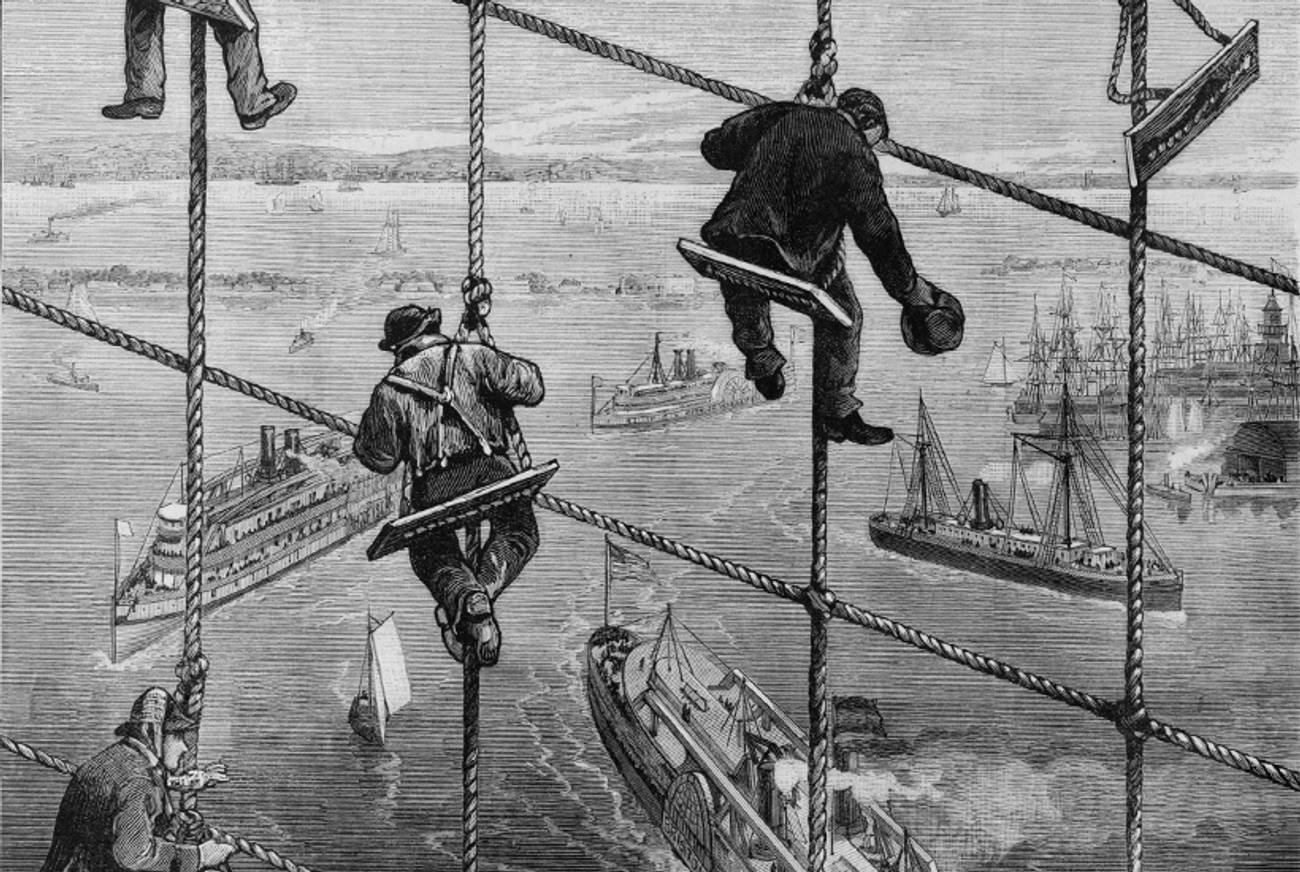

From Philadelphia, Cahan made a beeline for New York, arriving by train and ferry on the morning of June 7, 1882. He was twenty-two years old. At the time, no Statue of Liberty stood guard over the harbor, Ellis Island was a military post, and the Brooklyn Bridge wouldn’t be completed for another year. Horse-drawn streetcars and elevated steam railroads served as the primary mode of public transportation, and the tallest building in Manhattan had but ten stories. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, where the German-speaking Jew who interviewed him seemed a “heartless bourgeois…. He probably suspected that I was a wild Russian.” Cahan would later realize that other “Yahudim [German-American Jews]…fervently wished to help us stand on our own two feet in the new homeland.”

Cahan immediately set out to catch up with his socialist friends from Vilna, who were living in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint. His comrades were overjoyed to see him, he wrote later; he considered them “the first Russian-Jewish intellectuals in the United States.”

The group had been met with hostility by German Jews, who had begun to arrive in America in the 1840s and had gradually displaced the long-established, assimilated Sephardic Jews as the country’s largest and most influential Jewish ethnic group. The Germans “considered us to be atheists and lunatics; we intellectuals thought of them as ignorant, primitive people,” Cahan wrote. As socialists, Cahan and his comrades were only a tiny minority even among the recent eastern European immigrants. “The Jewish masses in the old country knew little about socialism,” Cahan wrote. “A mere handful of Jewish workers in Vilna had grasped the meaning of socialism—and almost all of this handful had come to America.” The new immigrants were a great deal more sophisticated than the Marxist factions who wanted to set up Communist-type farm colonies in the new world. It took all of three days in America for Cahan to realize that starting a communal agricultural colony “was not really my dream.” He was drawn to life in the city.

In 1882, when Cahan arrived in New York, the Jewish community was at the beginning of an enormous transformation. The Lower East Side was largely populated by Irish and German immigrants. There were small Jewish-owned shops, but no cafes or restaurants. The arrival of great numbers of eastern European immigrants in the 1880s swelled the number of Yiddish-speaking residents in the neighborhood. By 1890 the Lower East Side was one of the most densely populated areas in the United States. Irving Howe notes in World of Our Fathers that the small neighborhood contained “two dozen Christian churches, a dozen synagogues (most Jewish congregations were storefronts or in tenements), about fifty factories and shops (exclusive of garment establishments, most of which were west of the Bowery or hidden away in cellars and flats), ten large public buildings, twenty public schools and parochial schools—and one tiny park.”

Cahan boarded at the home of a widow on Monroe Street, between Catherine and Market Streets; from his window he could hear the clip-clop of horsecars on the Bowery and the iceman’s cries of “Ice! Ice!” on unbearably hot summer days. He paid for his board by teaching his landlady’s son to write Yiddish and read Hebrew, even though “I learned more English from him than he learned Hebrew from me.” His fellow boarders, who spoke a poor Yiddish that was sprinkled with American words and expressions, furthered his education, however much he may have looked down on them for their bastardization of their mother tongue—“non-Yiddish Yiddish,” he called it. Displaying a determination similar to the one he would cultivate years later within the immigrant readership of his newspaper, Cahan diligently studied English at night, relying upon Appleton’s English Grammar, a textbook specifically for German-speakers who wished to learn English.

He worked in factories by day—first making cigars, then tin. This monotonous work did not come easily to him. “Every hour of work seemed like a year,” Cahan wrote. He was not alone in feeling this way. The factories were filled with young, educated Russian Jewish immigrants, like Bernard Weinstein, who was to become secretary of the United Hebrew Trades, a federation of predominantly Jewish trade unions; Cahan converted him to socialism over long hours of laboring together in a cigar factory. The same cigar factory employed Samuel Gompers, the future president of the American Federation of Labor, but on a different floor.

In The Downtown Jews, Ronald Sanders points out that the presence of so many educated workers in factories made for a situation that was unique in labor history: factories now “contained a large class of proletarian intellectuals, who brought an articulate class consciousness right into the shops.” Cahan described how it felt in his memoir: “The worker was being reduced to a dead tool. These things I had previously read in books on political economy, and now I would say to myself, ‘Here I am, a dead tool like the rest.’ It fascinated me that the facts were just like the books said they were.”

In June 1882, the same month Cahan came to New York, a strike broke out on the waterfront among the longshoremen. Many were immigrants from Ireland and Germany, and they agitated for a raise in pay. The foreman went down to Castle Garden (New York’s port of immigration at The Battery from 1830 to 1892, when Ellis Island replaced it), on the hunt for able-bodied men right off the boats to replace the strikers. They offered jobs to the mostly Polish and Russian Jews—without telling them they would be crossing a picket line. Isidore Kopeloff (who would later be active in the anarchist movement) was one of the strike-breakers. Several longshoremen came to the newly hired workers, saying “we were scabs who were taking the bread out of the mouths of the strikers’ families,” Kopeloff recalled. “…I couldn’t understand what I was doing wrong or what my sin was. Why should I not be permitted to earn my piece of bread? And what was this union, and why were those for it kosher and those against it treyf?”

A group of Jewish intellectuals formed what they called a Jewish socialist propaganda society and handed out leaflets in Yiddish advertising a town hall meeting on Rivington Street. Its goal: to convince fellow immigrants not to cross the picket lines.

On July 7, Eisl’s Golden Rule Hall at 127 Rivington Street was packed with several hundred people listening to orators speaking in Russian, the language of the radical intellectuals. Using Yiddish to lure people to an event was acceptable, but to fire them up politically, only Russian would do. At the meeting’s end, when the floor was thrown open to members of the audience, a man who looked younger than his twenty-two years approached the podium with a “thumping heart.” Abraham Cahan had been in America for only a month, yet he was speaking in public for the first time.

When Cahan rose to speak, some people, apparently with no time for a newcomer, “started for the door.” Speaking in Russian, he declared: “We have come to seek a home in a land that is relatively free. But we must not forget the great struggle for freedom that continues in our old homeland. While we are concerned with our problems, our comrades, our heroes, our martyrs are carrying on the struggle, languishing in Russian prisons, suffering at hard labor in Siberia. There is little we can do at this distance. We can raise money to aid the sacred cause. And we must keep the memory of that struggle fresh in our minds.”

His words made him, as he himself puts it, the “hero of the day.” And he had established a pattern that would pervade all his later writings. For all the posturing of the socialists about being the wave of the future, in practice Cahan was also obsessed with an obligation to not forget the past.

Later in the evening, a friend named Mirovitch told Cahan about the propaganda society, explaining that its aim was to spread socialism among the Jewish immigrants.

“If it is for Jewish immigrants, why are the speeches in Russian and German?” Cahan asked.

“What language do you suggest? What Jew doesn’t know Russian?” his friend replied derisively.

“My father,” Cahan replied sharply.

Mirovitch, who hailed from cosmopolitan St. Petersburg, didn’t speak Yiddish and couldn’t fathom the world from which Cahan had come. “Why don’t you deliver a speech in Yiddish?” he suggested, laughing.

“Why not?” Cahan replied.

And so was born a career in which the medium of Yiddish became part of the message.

The following Friday night, the propaganda society rented a hall in the back of a German saloon on East Sixth Street. Some four hundred people crammed into it and heard what Cahan called “the first socialist speech in Yiddish to be delivered in America.” His topic was Marx’s theory of surplus value and “the inevitability of the coming of socialism.”

In advance of his next Yiddish speech, on Suffolk Street, he and his friend Bernard Weinstein handed out hundreds of Yiddish leaflets on the streets of the Lower East Side, which Cahan had printed at his own expense. This new hall was much larger, but Cahan still packed them in; some of the audience members were forced to stand. Others, including a dark-haired young woman wearing a pince-nez (at whom Cahan kept glancing) stood on tables. His talk “kindled a wave of excitement… as if the dumb had begun to speak,” Weinstein later recounted. Cahan spoke for three hours, cursing the millionaires “with elaborate Vilna curses” and shouting for workers “to march on Fifth Avenue with their tools and their axes and to seize the palaces and the riches which their labor had produced.”

Did Cahan truly envision that shirtmakers of Canal Street with their metaphorical axes would storm the upper avenues of Manhattan? Not likely. As Irving Howe explains, such speeches were “typical of the movement, with its mixture of Marxist approximations and anarchist bravado, its verbal radicalism at once innocent and empty…. Not everyone was certain as to which he really was, or what the differences amounted to, and some, like Cahan, shifted back and forth between anarchism and socialism before coming to a halt.” Cahan himself seemed aware of his ambivalence, even if he didn’t publicly acknowledge it. “It is a joke,” he wrote to an old Russian friend in 1883. “I debate, I argue, I get excited, I shriek, and in the middle of all this, I remind myself that I am a vacant vessel, an empty man without a shred of knowledge, and I begin to blush. I am ashamed of myself.”

Even as he was calling for violent marches, Cahan was being seduced by America. “The anarchists and even the socialists argued that there was no more freedom in American than in Russia,” he wrote in his memoir. “But that was just talk, I concluded.” There was no czar, “no gendarmes, no political spies.” One could say and write whatever one wanted.

And what Cahan wanted was to speak in and write English. All that work with Appleton’s English Grammar was paying off. After just a few months in New York, he began giving English lessons to other immigrants, and soon he was earning enough as a tutor to quit the factory. But remaining one linguistic step ahead of his fellow immigrants was not good enough for him; he wanted to master the new language.

In the fall of 1882 Cahan approached the principal of an elementary school on the corner of Chrystie and Hester streets, not far from where he lived, with an unusual request. In “careful but tortured English” he explained that although he had been a teacher in his old country, he wanted to be a student in the new one. The principal granted him permission, and for the next three months the twenty-two-year-old Cahan sat in on classes, joining thirteen-year-old boys in their lessons in reading, writing, and geography. He studied his fellow students as well, so as to learn their mannerisms as well as their pronunciation. It was not simply English he wanted to conquer, but American English, in all its idiomatic complexity. By winter, he had picked up enough to sail through the American daily newspapers. And soon he was speaking English with only a hint of an accent.

This essay was excerpted and adapted from The Rise of Abraham Cahan, out today from Nextbook Press.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.