Animating the Love, Hope, and Despair of the Forward’s Legendary Advice Column

In ‘A Bintel Brief,’ Liana Finck draws a love-letter to the cowards, stoolies, brides, and sons who inspired Abraham Cahan

One of the mysteries of the life of Abraham Cahan is why in mid-career he quit writing fiction. By the end of World War I, Cahan, the editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, had met with much success with The Imported Bridegoom, Yekl, and The Rise of David Levinsky. Then suddenly, with more than 30 working years ahead of him, he quit. It bothered a lot of people, including H.L. Mencken. My own theory is that Cahan got wrapped up in the struggle against communism. But it may just be that the stories bubbling up on the Lower East Side were better in real life than anything Cahan could conjure.

A Bintel Brief, Love and Longing in Old New York, a wonderfully illustrated gem of a book by Liana Fink, would confirm the latter view. In it, Finck tells some of the tales from readers that came into the Forward each day and were answered by Cahan or the other editors in the famous column known as the “bundle of letters.” They wrote of missing the old country and being confused by the new. They sought advice on the problems that beset them in the new world. Some were mundane, such as how to use a handkerchief, or whether to play baseball. Others were profound.

The eleven stories illustrated by Finck are particularly choice. They start with one of the most famous letters, from the woman who told her son “not to be such a good boy.” But he worked in the sweatshop until his fingers bled and saved his pennies until he had enough money to buy a watch. At one point, the family pawned it to buy food, but got it back. Eventually, though, it “disappeared.” She suspects the woman down the hall, and writes to the Forward in hopes that the suspect will see the letter and return the watch. She promises “we will remain friends like we always have been.”

Cahan advises that the “letter-writer is in a bad situation” and that “it can be that she has let her imagination run away with her.” So he goes off on a harangue about the “wretchedness of the workers lot.” Not that Cahan is indifferent. He allows that the story “pierces our hearts” and adds: “If these lines were to portray how hundreds of workers kill themselves each day, it would make less of an impact than this small but extraordinarily human story about the watch and chain.” I’ve read that story several times over the years, but rarely savored it quite the way I did with Finck’s book.

This is because of the drawings. It would be over-stating the case to suggest that this is a graphic novel, but that’s only because it is more in the nature of a collection of stories. The art does the same thing. The book’s jacket characterizes it as a “mash-up of Art Spiegelman’s deft emotionality, Roz Chast’s hilarious neuroses and the magical spirit of Marc Chagall.” That’s a tall order. Let’s just say the drawings do their share of the work in bringing Cahan’s craft to life without turning the Bintel Brief into children’s stories.

One of them is called “Nasye Frug” and forecasts, en passant, the bridal registry. The letter comes from a woman who has a dream the week before she is about to become Mrs. Yankel Frug. Before the wedding her friends bring over their gifts. As they’re opened, the hapless bride discovers 52 feather pillows and 38 lamps. In the midst of opening this larder one of her countrymen exclaims “Fools! What did you bring?” She writes to the Forward to ask whether the crank had a point. Cahan reckons he is on to “a very good plan indeed.” Now, of course, bridal registries are a multi-billion-dollar business.

“Former Assistant Detective” is the name Finck gives to one of the letters she illustrates. It is the classic about the informant who is being paid by the police to spot pickpockets and thieves. He is assigned to a café that is selling liquor without a license. There he spots the owner’s “seven children with their pale, emaciated mother” and realizes he cannot send the father to jail. The lieutenant insists he go back with the complainant himself, who confesses en route that the café owner owes him four dollars. Cahan advises the stoolie to flee this work lest he himself fall into “immoral police practices.”

Finck includes here the story of the girl who was born in America and gained an education but found herself not yet ready to accept the proposals coming her way. Her parents send her for a six-month sojourn to the their hometown in Russian Poland. There she falls for a “handsome, clever, refined” fellow who is “a brilliant talker.” They become engaged, and she brings him back to America, where he is mocked by her friends as a primitive and a greenhorn. He still loves her, but what should she do? Cahan’s answer is a classic.

How astonishing are the stories that were brought to Cahan. One is from a “mad barber,” who falls asleep while reading the Police Gazette and dreams that while shaving a customer he cuts off his head. After awakening he becomes obsessed and gets sudden impulses to do what he did in his dream. Should he give up his job? The answer from the Forward is classic of Cahanian stoicism. But the greatest of the Cahan answers—or non-answers—is the one to the coward who can’t stop thinking about his father.

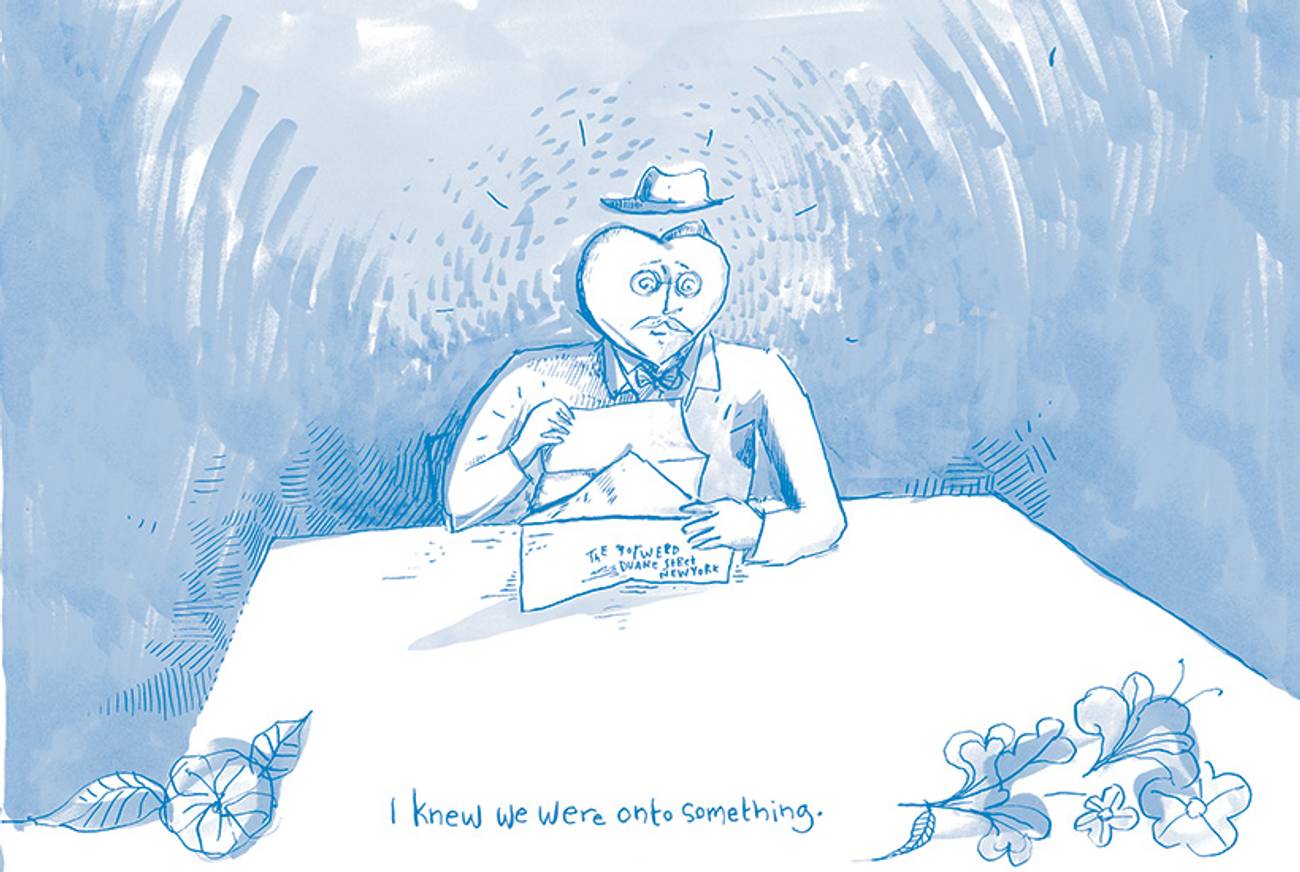

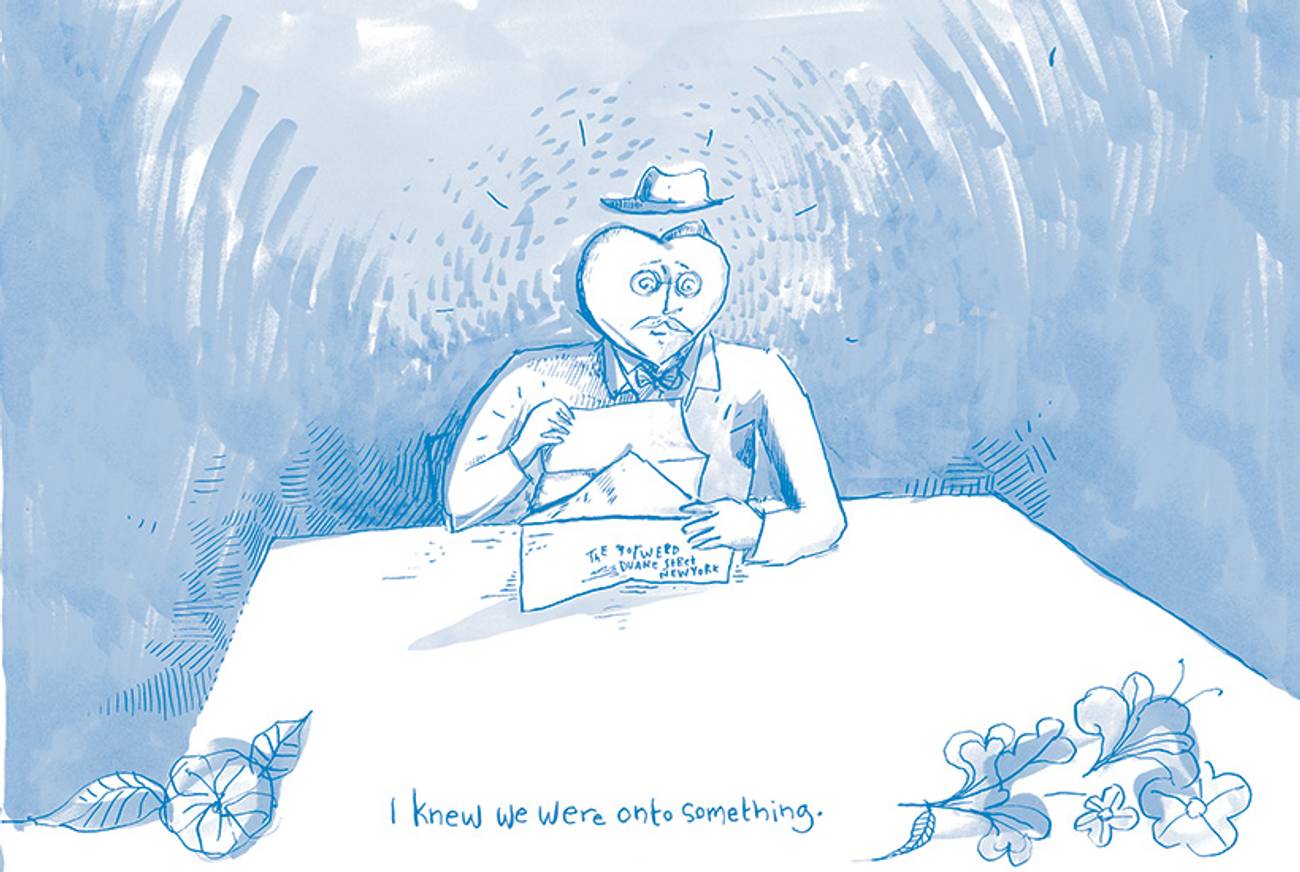

The coward is tortured by the fact that on the night of a pogrom he was reading outside and saw the thugs coming but failed to warn his family. “I ran without knowing what I was doing,” he confesses. Now in Brooklyn in the year 1906, he hears from his family that they survived but that his father lost the use of one of his arms. His sisters want to bring him to America. What is Cahan’s advice? It reminds me in an odd way of “A Medieval Romance,” the story in which Mark Twain wove a plot so complex that he couldn’t untangle it. Liana Finck shows Cahan at his typewriter, composing a reply, his head shaped like a heart.

***

For a slideshow of images from Liana Finck’s A Bintel Brief, click on the icon to the left.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.