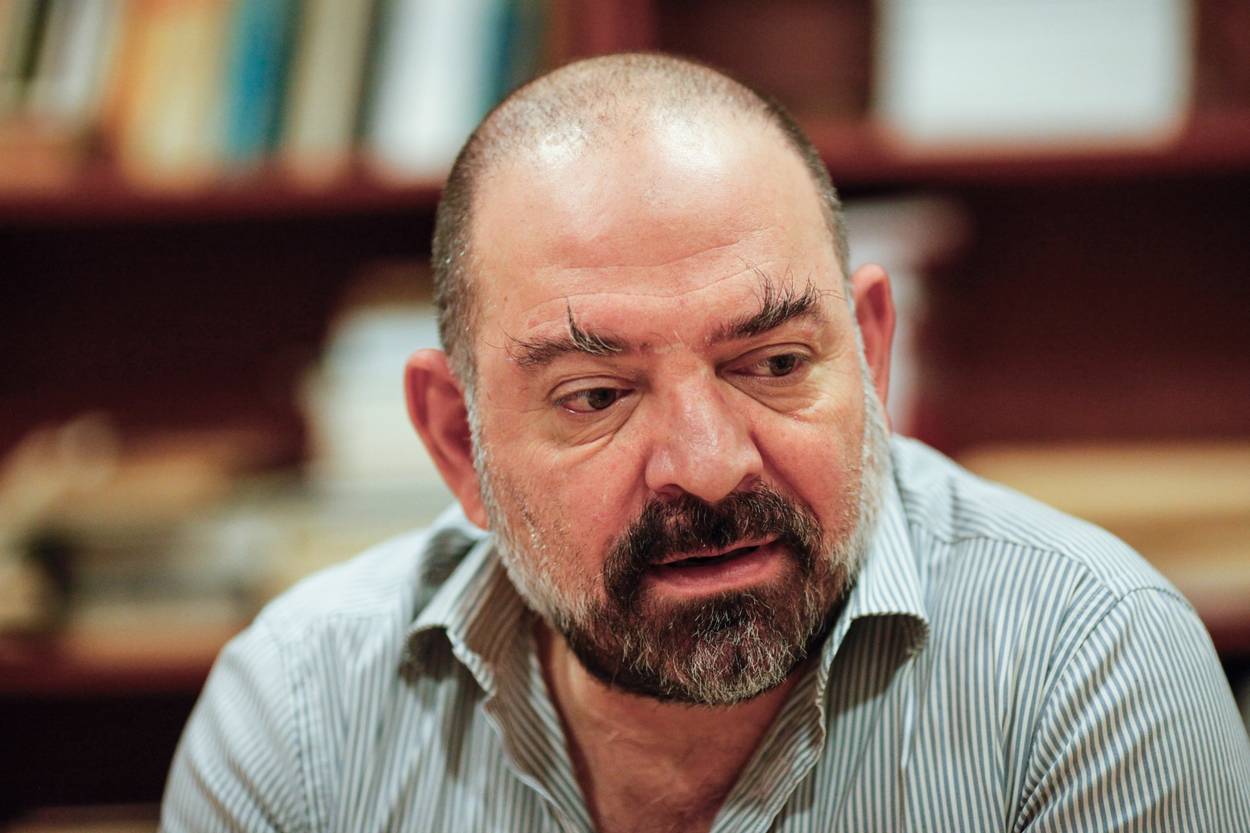

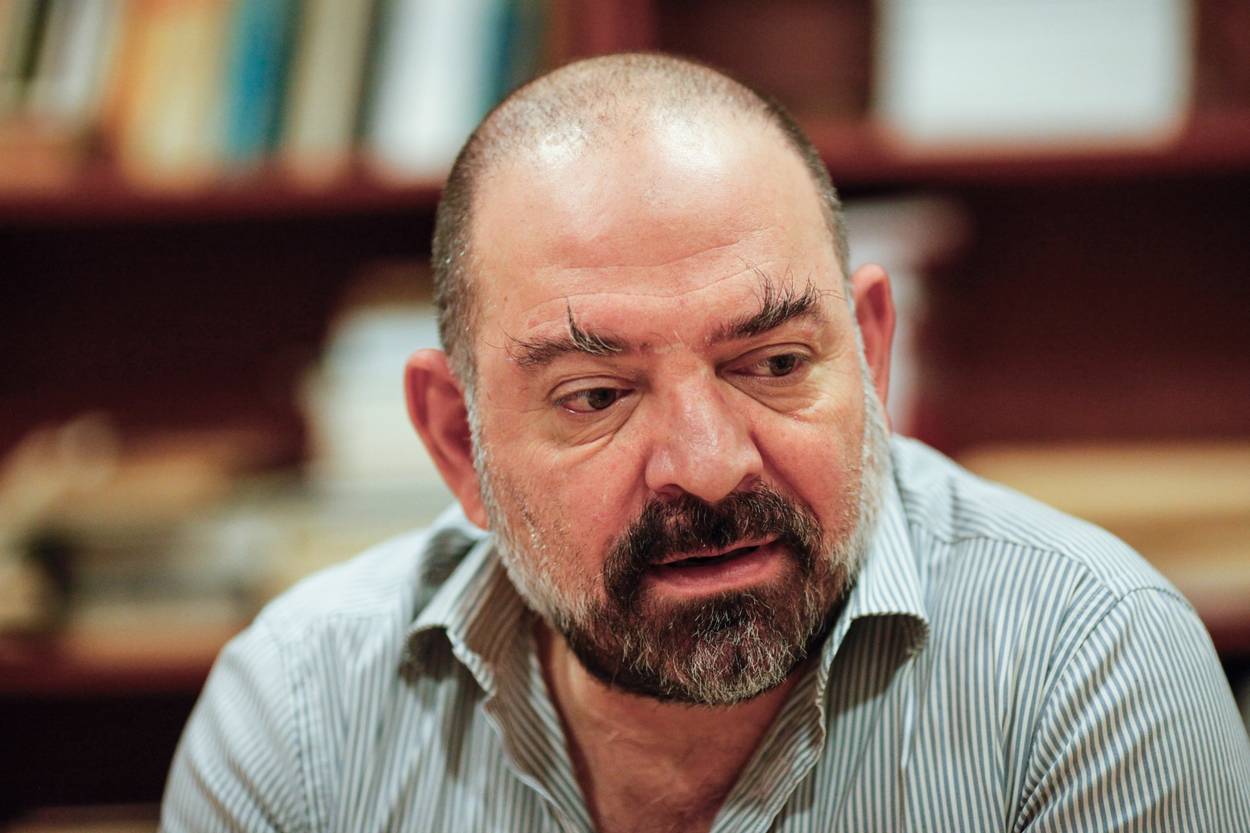

In Memory of Lokman Slim

The philosopher, activist, filmmaker, writer, and publisher, a prominent Hezbollah critic, was killed last week

A few years ago, Lokman Slim and I were driving through Hezbollah-controlled areas in southern Lebanon, not far from where his body was found last week. We passed through small Shiite villages festooned with commemorative banners of soldiers killed in the Syrian war. He noted the ages of the fighters pictured, mostly boys in their early teens. Estimates at the time suggested that Hezbollah had lost 2,000 troops in the conflict. Lokman had learned that senior Hezbollah military commanders were worried that defending Syrian dictator Bashar Assad in his genocidal war against Sunnis would come back to haunt Lebanon’s Shiites. Lokman said he thought that the Party of God’s days were numbered.

“I saw the birth of Hezbollah,” he told me. “It is not divine, but a human thing, which means it has a lifespan. I will see its end as well.”

The 58-year-old political activist loved the Shiite Muslim community he came from and he was determined to save it from Hezbollah, which wanted to keep the Shiites poor, fearful, and dependent. On Thursday night, his body was discovered in a car near the village of Addoussieh where he had been shot to death.

Lokman had friends throughout Lebanon. He was warm, generous, funny, and won the loyalty of everyone from waiters to writers and former fighters to army generals by being loyal first. He was a philosopher, activist, filmmaker, writer, and publisher whose way of describing the world was so startlingly unique that it was hard not to think he’d saved his best new idea just for you. But he was prolific, so he left everyone who spoke with him something new to think about.

He explained to me why it was important to reconcile with Lebanon’s neighbors, including Israel. “If I can stop fighting against them,” he reasoned, “then I can start talking to them.”He himself had fought alongside the Palestinians in the war against Israel that they waged from Lebanon. He’d told himself that if he survived Ariel Sharon’s 1982 offensive he’d leave both the war and Lebanon. He moved to Europe, where he studied philosophy and ancient languages at the Sorbonne.

On our drive through the south that day, we visited friends of his a few miles from the Israeli border for lunch. The Lebanese will tell you how beautiful their country is but in fact much of what may have once been richly verdant is now an eyesore, overrun with garbage, the vistas pockmarked with crass billboards and ugly buildings. But where we drove that afternoon truly was beautiful. And quiet. If you spent enough time with Lokman, you might come to see that at times even nature had a certain Shiite quality, modest, witty, surprising. We drove through a small valley where an Israeli tank had been abandoned during the 2006 war. It made all else around it seem more green, wild, delicate, and eternal.

It was not the beauty of the natural landscapes of Lebanon that drew him back home, though. In the early 1990s, Lokman was called back to Beirut by his family to help a young relative who had gotten involved with Hezbollah. Lokman spent the rest of his life in the capital city’s southern suburbs where he was born and raised, trying to save young Shiites from nihilism disguised as religious devotion.

You didn’t have to love death, he taught. You had choices, after all. Thus, much of the political organizing he did seemed only tangentially related to politics. He wrote and directed films, he ran an art gallery, he published dissident Shiite clerics, as well as poets and fiction writers, he helped businessmen with projects that showed the Shiite community they didn’t need to depend on Hezbollah’s handouts.

My favorite Lokman initiative was a Lebanon-wide project that brought together women from different religious communities, classes, and backgrounds to teach them English. Some of them had not graduated high school, some couldn’t read, many had to fight off resistance from their fathers or husbands to take the class. For him, politics was an intimate, often sentimental, affair. “How can they hate America like Hezbollah teaches them,” said Lokman, “when they’re speaking English on Skype or FaceTime with their grandchildren in America?”

The graduation ceremonies were amazing celebrations, the women on stage smiling broadly, proudly displaying their certificates to show they’d finished the course. What couldn’t they accomplish next? How could they hate stingy and corrupt Lebanon, when Lokman made it seem like a land of opportunity? May generations of Lebanese women who will never know Lokman Slim raise their sons to know there are options in life beyond the party of death.

Lokman’s sister said after she got news of his assassination that “murder is an undignified act.” Indeed, taking a life is a shameful thing and shame is Lebanon’s curse from the fratricidal wars between 1975-1990 during which more than 150,000 Lebanese were killed, most of them by other Lebanese.

For Lokman, reconciliation started with the country’s once-warring sects embracing their own identities. He wanted the Maronites to be as Maronite as possible, the Druze to be Druze, the Sunni to fulfill their Sunniness. But no one compared to his beloved Shiites, and he made a compelling case for his people. We went from one Shiite-owned bar to another decorated with the pictures of great figures from the Shiite past, poets, musicians, artists, historians. In a sense, it was his family album and he was showing where he belonged in a tradition of men and women who embraced life and longing, the desire for more life.

Some Lebanese used to say they distrusted him—how could such an outspoken opponent of Hezbollah, someone who challenged them publicly for decades from within their own strongholds, get away with taking on a gang of psychopathic murderers who held the Shiite community and all Lebanon hostage unless there was some tacit agreement? What they didn’t know was that Hezbollah was always threatening Lokman. He kept going anyway.

No one doubts that Hezbollah killed Lokman Slim, and no one knows why they chose to kill him now. Some say Hezbollah was scared that he had lately touched on especially sensitive issues. Some say that with the new U.S. president determined to reenter the nuclear deal with Tehran at any cost, Iran’s asset in the eastern Mediterranean calculated that no one would come asking about killing the man Hezbollah called the head of “the Shiites of the U.S. Embassy.” Or maybe it had nothing to do with geopolitics. Hezbollah it must be remembered is a terrorist organization run by psychopathic murderers and what they do is kill people. And yet some others say Lokman was killed because he was winning.

He did not live to see the end of Hezbollah but he knew that his real calling in Lebanon was to strengthen and increase the people of life. He fought for and protected those he loved and those who needed his love. And he inspired others, too, and they will continue to fight and love, though no other man is Lokman Slim.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).