Lost in Translation

What Proust taught me about being Jewish

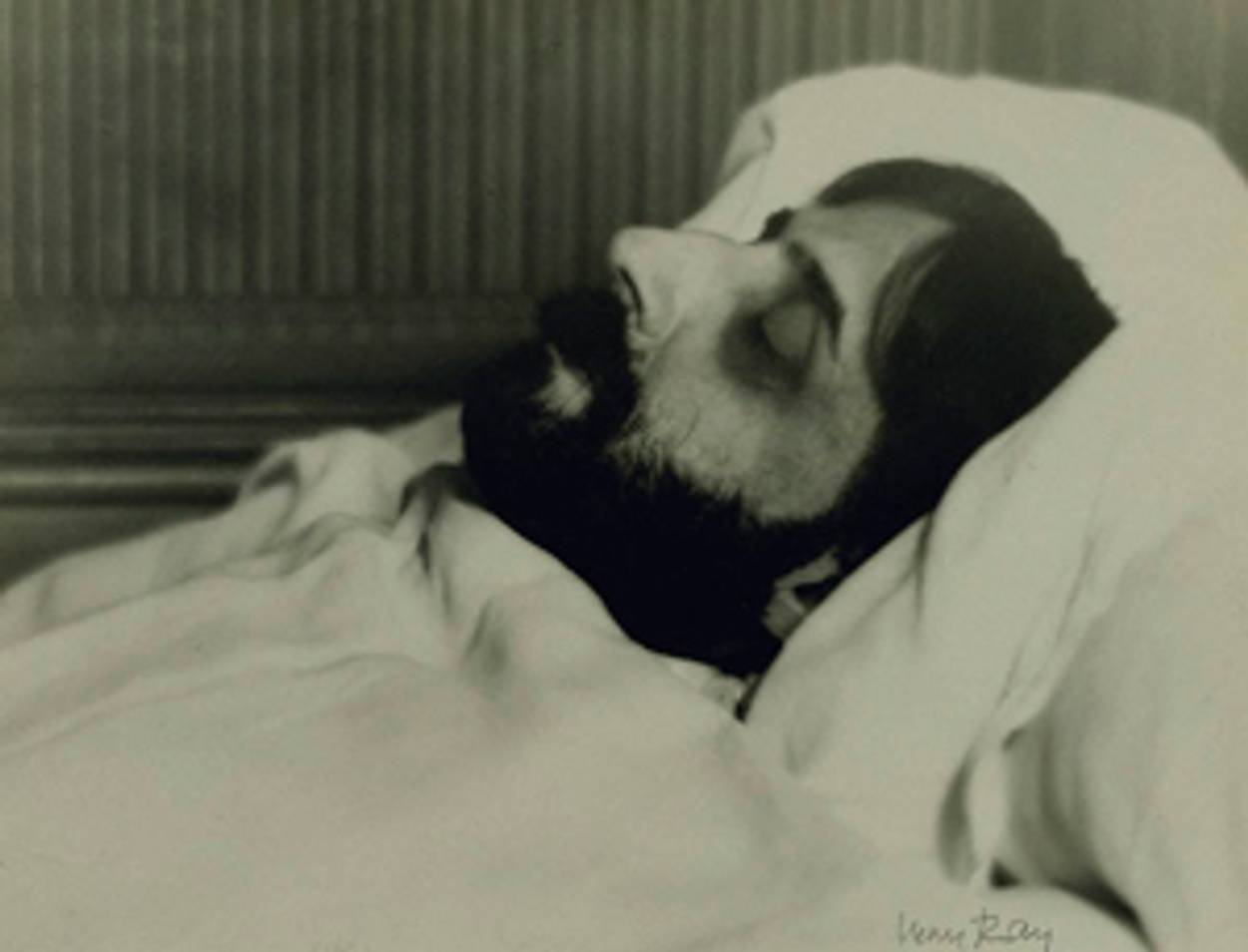

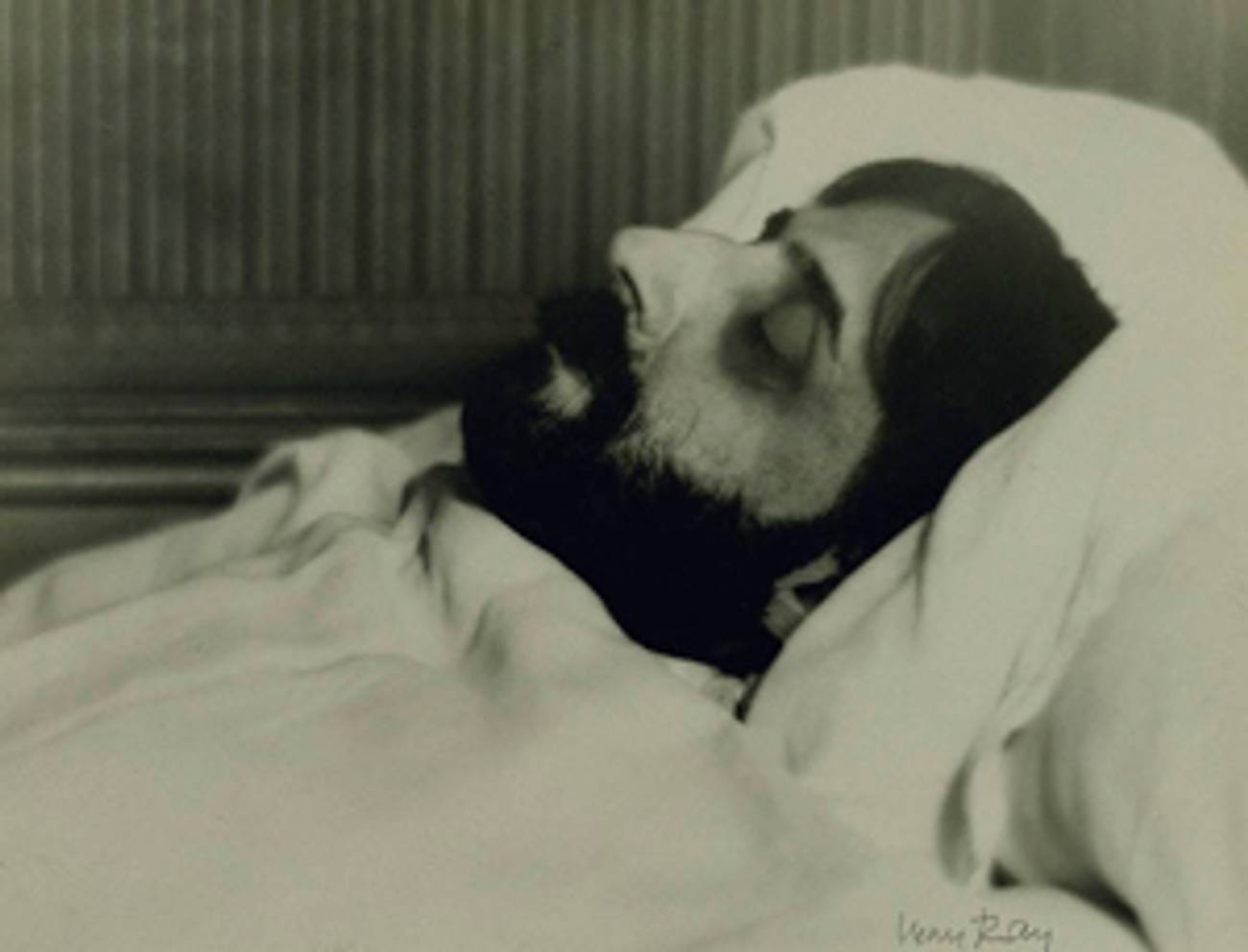

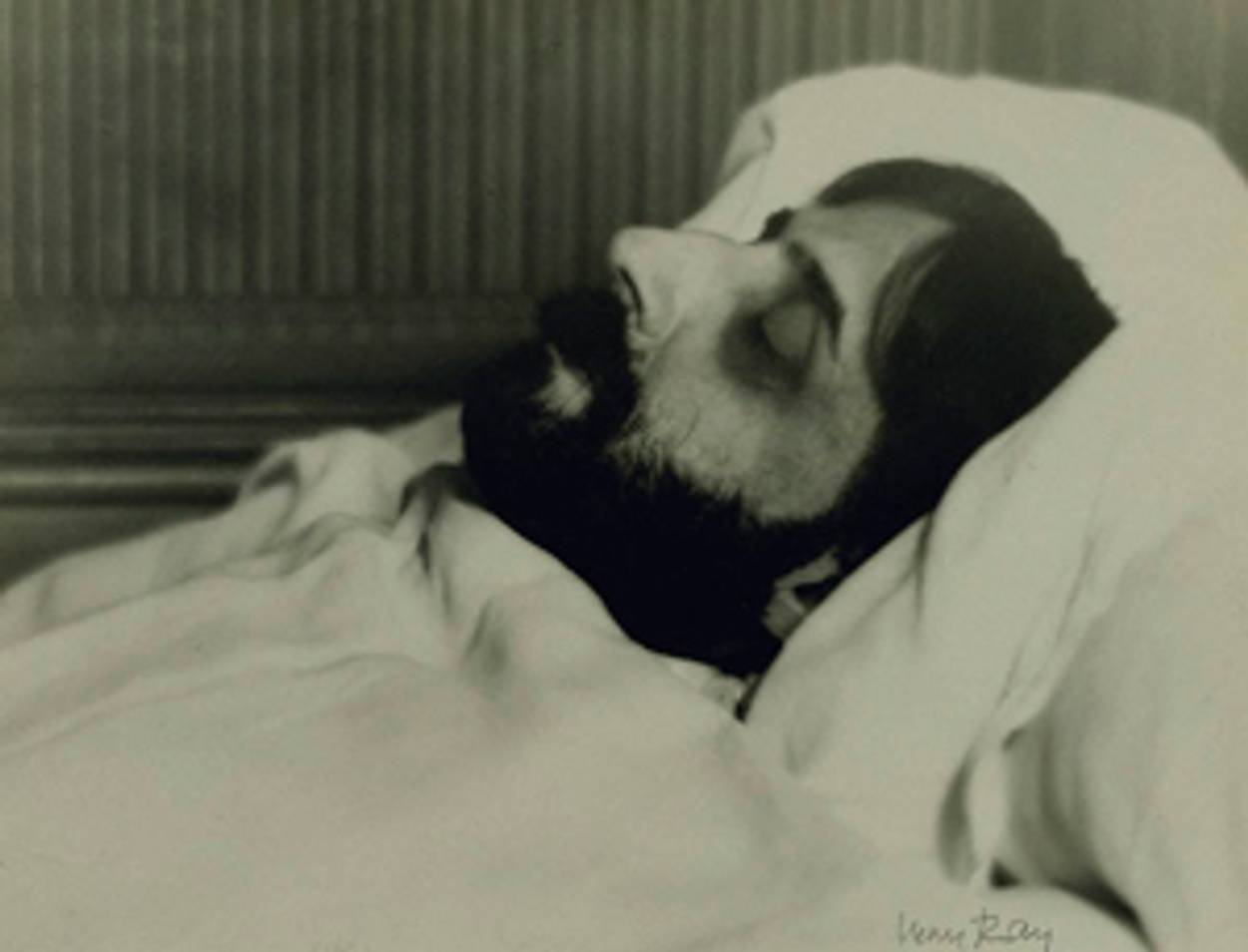

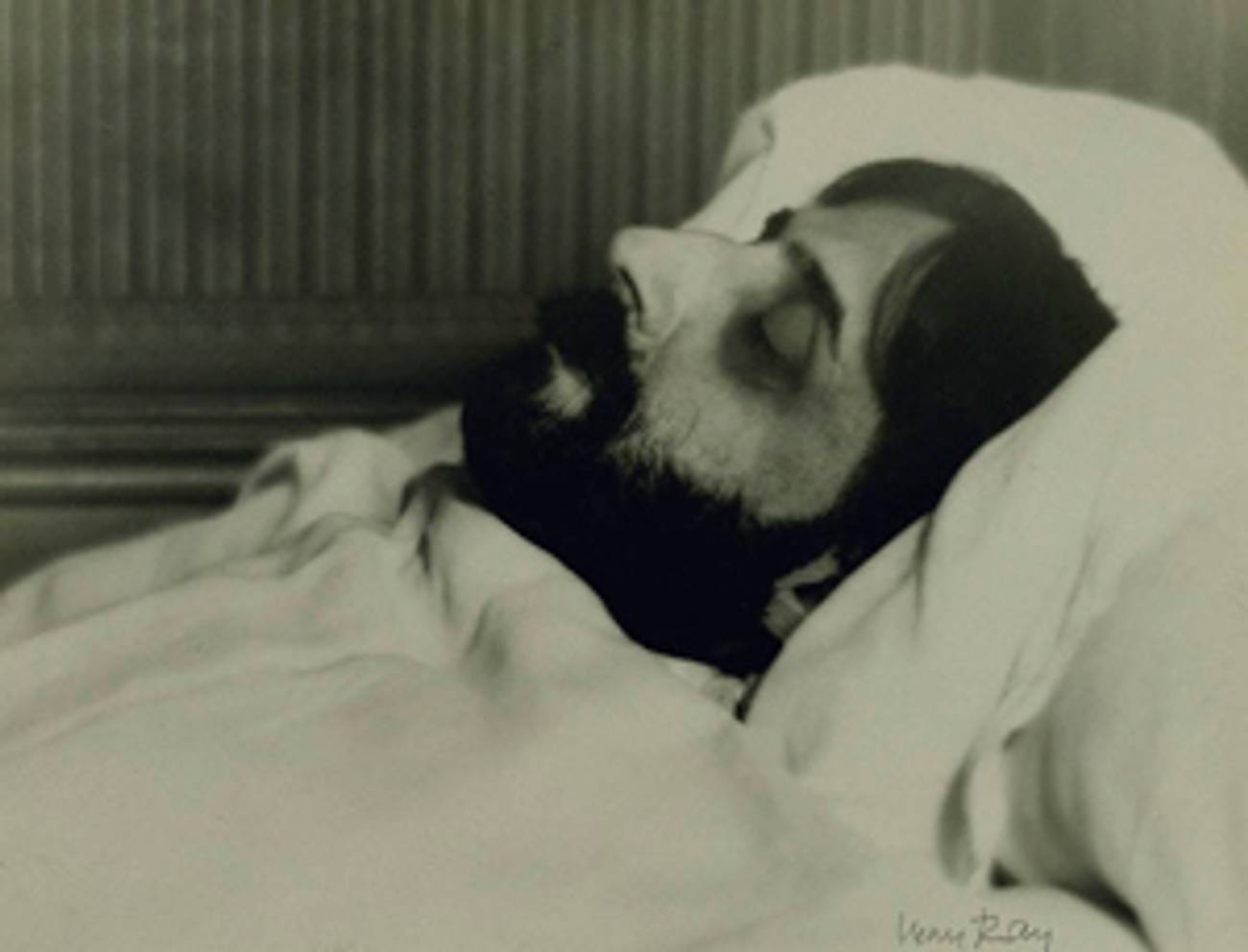

The first time I saw Marcel Proust, I fell madly in love with him. He had just died, and was therefore unable to stop Man Ray, a recent arrival to Paris, from sneaking into his cork-lined bedroom and snapping a photograph. In it, Proust’s eyes are sunken, his hair long and black, his alabaster face as thin as a child’s. He looks as though by writing In Search of Lost Time he was finally able to rid himself of any trace of corporeality, translating himself from flesh to fiction.

I bought a postcard reproduction of that picture in a used book store in my native Tel Aviv in 1991. I was 15, and while most of my friends spent their afternoons working out in anticipation of our pending conscription to the Israel Defense Forces, I spent most of mine staring at my photo of Proust. This, I thought, was how a writer, a real writer, looked. I had to read him.

But In Search of Lost Time was not yet available in Hebrew, and would not be until a year later. So I struggled to read it in French, and was soon so entirely consumed by it that I glided through my own life, disinterested and detached, caring only about Proust’s universe, looking desperately for traces of his charming French countryside town in my modern Mediterranean metropolis.

With an adolescent fervor generally associated with indie-rock bands or budding romances, I wanted to share Proust with my friends. But few of them could read French. In a moment of hubris that amazes me still, I decided to attempt a translation.

That my linguistic credentials were sorely lacking—a few years’ worth of weekly afternoon sessions at the home of Madame Lily, the French tutor my mother had hired, and a small personal library of French books that, until I discovered Proust, consisted largely of a series about Mon Ami Chocolat, an affable little brown lamb—bothered me not at all. Translation, I strongly believed, was about more than the ability to rewrite the same sentences in a different language. It was about transformation.

The now sadly forgotten German writer Rudolf Pannwitz put it best. Our translations, even the best ones,” he lamented back in the 1930s, proceed from a wrong premise. They want to turn Hindi, Greek, English into German instead of turning German into Hindi, Greek, English.” In other words, a great translation depended less on accurately conveying the information contained in the original work and more on faithfully capturing its spirit or its essence.

As I began my project, my confidence plummeted. Proust’s French, I realized, was a language as intricate and delicate as lace, whereas my Hebrew, the Hebrew of late-20th-century Israel, was as rough and durable as denim. Proust’s was the language of hints and implications, of page-long paragraphs describing slumber or a song; mine was the language of biblical commandments and military commands, of thou-shalt-nots and of drop-down-and-give-me-twenties.

The challenge ahead, I decided, required a strict regimen, much like the one that enabled Proust to produce his towering novel. I decided to emulate my hero: like Marcel in his cork-lined room, I spent most of my free time sequestered in mine, perched over a desk that I had cleaned of everything save for a copy of the novel, stacks of legal pads, my favorite fountain pen—translating Proust with a Bic seemed somehow blasphemous—and that photograph, in a cheap wooden frame, my memento mori. Let others train their bodies; I was training my mind.

The first sentence of Within a Budding Grove, the novel’s second volume, offers a good sense of what I was up against. I quote it here in translation, of course, from the excellent—definitive! essential! irreplaceable!—version produced by C.K. Scott Moncrieff in the 1920s, revised six decades later by Terence Killmartin, and then again by D.J. Enright (that three men were needed to produce the quintessential English edition speaks volumes):

My mother, when it was a question of our having M. de Norpois to dinner for the first time, having expressed her regret that Professor Cottard was away from home and that she herself had quite ceased to see anything of Swann, since either of these might have helped to entertain the ex-ambassador, my father replied that so eminent a guest, so distinguished a man of science as Cottard could never be out of place at a dinner-table, but that Swann, with his ostentation, his habit of crying aloud from the house-tops the name of everyone he knew, however slightly, was a vulgar show-off whom the Marquis de Norpois would be sure to dismiss as—to use his own epithet—a pestilent” fellow.

It’s a classic example of the absolute clause, that most Proustian of fashions, an elegant and elusive animal that, lying motionless, tempts you to come near it and, when you finally do, leaps and runs in the other direction. The reader, of course, plunges into the sentence fully expecting the narrator’s mother to be the subject, when it is in fact the father, emerging midway through the sentence, to whom we should be paying attention. (André Aciman elegantly expands on this subject here.) Such is the beauty of Proust’s language, and such is the source of frustration for the many readers who found his structures too flummoxing.

And flummoxing they are, particularly for anyone aspiring to translate Proust into Hebrew. Hebrew, with its economical logic, with its three-consonant roots serving as the blunt building blocks of all language, with its tightly packed words each containing multitudes of meanings, Hebrew has little room for ornament. Like so many of the people who nowadays speak it, it is direct, impatient, eager to get to the point. Not for it are sentences like the one above, which take 123 words to make a simple point.

The same, of course, was true of the novel’s content. As I declined more and more of my friends’ invitations, mumbling that, for their benefit, I had to finish translating some 3,200 pages of a novel most of them had never heard of, they became concerned. They asked me what the book was about. The best answer, Gerard Gentte’s, is four words long: Marcel becomes a writer.” But my friends wanted more, and so I told them of princesses and marquises and madeleines and mothers and the other, delicate subject matters that pop up everywhere in the novel. As could be expected, they scoffed: Hebrew literature, the sinewy Israeli strand of which was virtually all we’d ever read, was about matters of life and death, hatred and heroism, solace and sacrifice. Its heroes, like Alik, the protagonist of Moshe Shamir’s novel Bemo Yadav (By His Own Hands”), were mythical men born of the sea, not, like Proust’s narrator, effete boys who vacationed in seaside resorts. Gradually, my friends informed me, some less politely than others, that they had no interest spending any time with what sounded like a fey, French, and antiquated novel. They were, for the most part, enthusiastic readers, but they demanded that the fiction they read relate to their own lives, that it address matters—the Arab-Israeli conflict, say, or the Holocaust—they found pertinent, that it evoke the smells and the sights and the sensations familiar to them. Even today, it is almost impossible to get a decent madeleine in Tel Aviv.

Months went by. Legal pads were filled with notes and questions about words I did not understand or sentence constructions that baffled me or cultural references that had me at a loss. I made little progress, completing, at the very most, two dozen pages of translation, and finding my work too inadequate to share with another living soul. Other interests and commitments beckoned. Slowly, I began to realize that my project was doomed.

Despite the preposterousness of my task, my failure was searing. For years, I found myself often thinking of Proust, and of the question of translation, and of what kept me from producing a serviceable Hebrew version of the book—my youth and shaky French notwithstanding.

And then it hit me. I was—how wildly appropriate—in Paris, now a 24-year-old ex-soldier who had left Israel behind for a life of voluntary exile, and I was spending money I didn’t really have at Mariage Frères, the legendary teahouse that almost certainly supplied the tisane into which Proust dunked his famous pastry. I was, of course, reading Proust.

What I failed to see as an aspiring translator, lost in the thicket of dangling particles and walled in by absolute clauses, was that while Proust’s French differed from my Hebrew and his Paris from my Tel Aviv, at the core we both shared a fundamentally Jewish worldview, an ancient mindset that argued that the only way to truly understand the world was to make the seemingly simple complex.

Walter Benjamin understood this all too well. Is it not the quintessence of experience,” he asked in his essay on Proust, to find out how very difficult it is to learn many things which apparently could be told in very few words?”

There are, in my opinion, few statements that capture quite so eloquently what it means to be Jewish. Isn’t the Talmud, after all, one long riff on how difficult it is to comprehend that which could’ve been much more pithily said? For generations, Jewish scholars have been toiling to make the straightforward complicated, understanding that only such complications can redeem us from the facile illusion of clarity and deliver us a more nuanced, more in-depth, and therefore more true, insight into life. As the Talmudists knew, only when we produce pages of commentary for every word in the scriptures can we truly get at their meaning; as Proust realized, only when we write at great length and intricacy can we truly get a closer look at the machinations of life.

This, I believe, is very much our Jewish heritage, as well as our key literary mission. Let the Hemingways punch out their short, declarative sentences. For us, a nation of priests, literature—and life—is about the beauty of complication, the grace of difficulty, the savagery of truth.

It is unlikely that I will ever refashion Proust into Hebrew, especially given the terrific existing translation by Helit Yeshurun. But while I remain a poor translator, I’ve become, I hope, a more astute reader, one who can embrace density and find in it small morsels of meaning. That alone is enough for me. As a certain French author once said, the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeing new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Liel Leibovitz is a writer currently living in New York. His second book, Lili Marlene: The Soldiers’ Song of World War II, is being published this month by W.W. Norton. He also writes Nextbook’s “Blessed Week Ever” column.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.