Lost Words

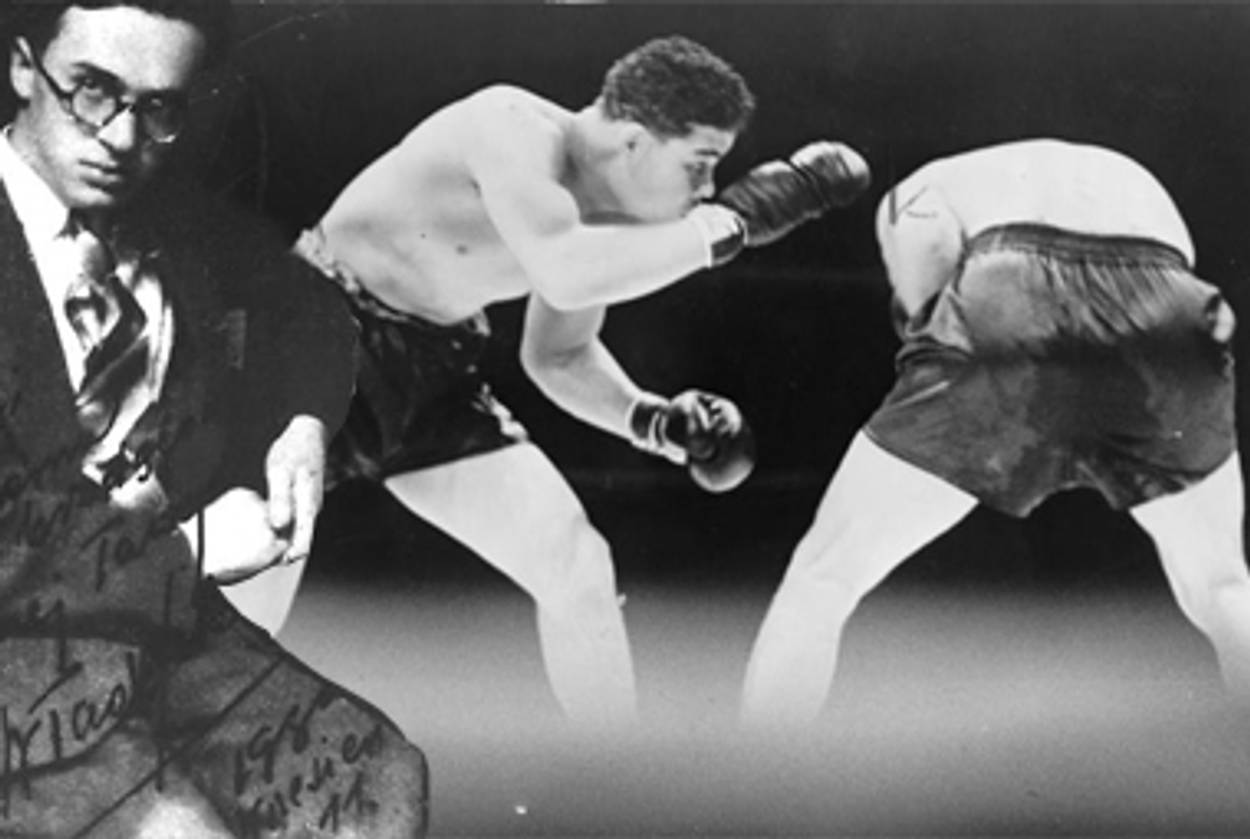

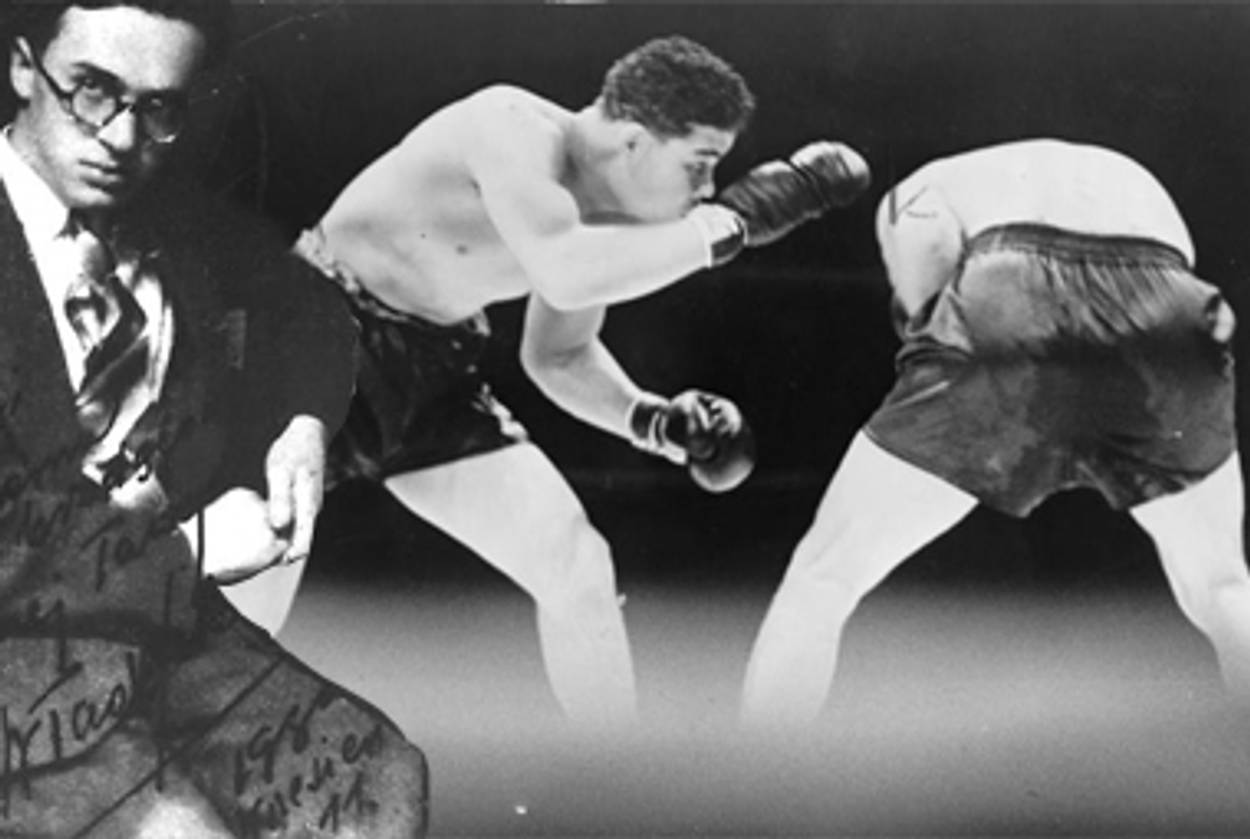

Władysław Szlengel, a forgotten Polish Jewish poet who wrote a verse celebrating Joe Louis’ 1938 victory over Max Schmeling, was once a celebrated and searing voice of the Warsaw Ghetto

How is it that books, especially books on historic topics, take forever to finish? One reason is that long after authors have gathered more than enough material, we still research compulsively—ostensibly for that precious but maddeningly elusive last detail, in reality to postpone that moment when we must let go. So, we turn over ever smaller stones. And sometimes, miraculously, beneath them we find gold.

By 2003, I had spent more than five years researching an event lasting only 124 seconds: the Joe Louis-Max Schmeling heavyweight championship fight of June 22, 1938. Because the key actors in that drama—an African-American hero on the one hand and Adolf Hitler’s favorite boxer on the other—were dead, along with all of the ancillary characters and nearly all of the 70,000 fans on hand at Yankee Stadium that night, newspaper reports were key. And I read them copiously: white papers and black papers, American papers and German papers and French papers and South African papers, papers on the left (the Daily Worker had a sports section, thanks largely to interest in Louis) and on the right.

One paper I’d neglected, quite understandably, was Nasz Przeglad. It was the Polish-language paper in Warsaw favored by many of that city’s more assimilated Jews, but I wasn’t sure it was available in the United States, and besides, it was long-since defunct; this is what happens to a publication when most of its readers are murdered. But shortly before the book went to bed, I decided to take a look, via an English-speaking friend in Poland. One of my theses was that no one was more interested in the fight than the Jews: By taking on Schmeling, who had defended Hitler’s regime from the outset, Louis was just about the only man around who was standing up to Hitler. Certainly no European leaders were. Surely, I surmised, the fight would have been followed closely in Poland, which had the largest—and, outside of Germany itself, the most menaced—Jewish community in Europe. Throughout Central Europe that night, one needed only to have stayed up late (the fight’s opening bell rang at 4:00 a.m. Warsaw time), tuned in to the Deutscher Rundfunk, and understood German to follow what was going on at Yankee Stadium. The Nazis had their own announcer—Arno Hellmis, who doubled as a reporter for the party’s leading newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter—at ringside, doing the play-by-play.

Given the late hour, Louis’ electrifying first-round knockout of Schmeling came too late for the European papers of June 23. But sure enough, on June 24, Nasz Przeglad (it’s Polish for “Our Review”) devoted much of its front page to the fight, including a witty description of the inconsolable Hellmis’ fractured, indecipherable account, one that had left much of Germany bewildered about what had actually occurred. (Contrary to the mythology, the broadcast was notinterrupted in mid-fight.) But most striking of all to me was a poem, set off in a large box on an inside page. It was titled “K.O.” and was dedicated to “the black man Louis who had defeated the German theory of racial superiority.” The author was named Władysław Szlengel, and its concluding, and by far most dramatic, stanza went as follows:

Hey, Louis! You probably don’t know

What your punches mean to us

You, in your anger, punched the Brown Shirts

Straight in their hearts—K.O.

It isn’t only novelists who fall in love with their characters. The same is true for writers of nonfiction, particularly if those characters have been misunderstood or forgotten—perhaps, subliminally, we hope that someday someone may do the same for us. One feels these things even more acutely with anyone who died prematurely or brutally or anonymously, robbed even of a fair chance at immortality. Who was Władysław Szlengel? When I first encountered him, I assumed he was just one more of the 6 million. Had anyone remembered him or his work, his name would certainly pop up in the card catalog of the New York Public Library, but it never had. Nor had he been mentioned in the pages of the New York Times. So, I resolved to bring him back to life. Even putting someone’s name in print can be a rescue operation; mentioning Szlengel in my book, and including a small portion of his poem, was the best and only homage I could pay. Mine turned out to be an imperfect tribute: I misspelled his name. Not surprisingly, no one corrected me. Virtually everyone who could have, died at the same time he did.

But much to my surprise, a friend who read my book—a student of Jewish Warsaw in the 1920s and 1930s—had heard of Szlengel. Belatedly, I did a Google search on him, and two things instantly became clear. First, he was not just another of Hitler’s faceless victims: His image, in a photograph he’d inscribed in September 1939, just a few days after Germany invaded Poland, suddenly appeared before me, a bookish and stern young man in a suit and tie, peering warily at the photographer from behind dark, round eyeglasses. And second, his poem on the fight was not some aberration but part of a much larger body of work, one that grew in sophistication and significance as his circumstances changed. Within three years, it turned out, Szlengel was to become one of the principal poetic voices of the Warsaw Ghetto.

“I don’t want to leave behind only statistics,” he explained in 1943, as the Nazis cleaned out the last remnants of Warsaw’s Jewish quarter. And he didn’t. His poems are among the most remarkable written testaments of the Holocaust, and yet, for a whole host of reasons, rooted in his chosen language and the sheer enormity of what happened and the nature of historic memory, almost no one knows them, or him. Szlengel would be famous if only he were not so completely forgotten.

Continue reading: Warsaw’s Jews, machers, and “The Frightened Generation.” Or view as a single page.

When half a million souls live in one small space, there will be many of everything, including poets, and in the Warsaw Ghetto there were presumably many of them. But none was as famous as Szlengel, whose poems both chronicled the annihilation of a people and buoyed them as it took place.

“The poems of Władysław Szlengel were read in the houses of the Ghetto and out of it, in the evenings, and were passed from hand to hand and mouth to mouth,” a survivor named Halina Birenbaum wrote in 1983. “The poems were written in burning passion, while the events, which seemed to last for centuries, occurred. They were a living reflection of our feelings, thoughts, needs, pain and merciless fight for every moment of life.”

Birenbaum first heard Szlengel’s poems as a 12-year-old in the ghetto, when her sister-in-law brought copies of them home from the factory in which she worked. By then, Warsaw’s Jews pretty much knew what lay in store for them: Before long, unless they died of disease or starvation beforehand, they would be rousted out of their apartments and cellars, crammed onto train cars at the Umschlagplatz, and sent to Treblinka, where they would be killed. There was little mystery about it. Szlengel’s words, she recalled, gave her hope: “That someone could write poems like this in the Ghetto meant that not everything was death.” Never did she set eyes on the man, nor, as far as I can tell, is there anyone still around who did. But she memorized his poetry, and later, in Majdanek and Auschwitz and after liberation, she carried it with her.

Among many other things, the Germans robbed the Jews of their biographies, and information about Szlengel is scant. The son of an artist, he was 24 years old and already relatively well-known around Warsaw when he wrote about Louis and Schmeling, having composed a variety of poems and songs, many of them satirical, for local cabarets. Unlike the majority of Warsaw Jews, who spoke Yiddish, he lived and wrote in Polish, an act of love for his native land and one that, as for most of Poland’s Jews, was rarely reciprocated.

“Szlengel reflected the sensibilities of the acculturated but unassimilated Polish-Jewish intelligentsia, caught between genuine Jewish pride and love of a Poland that would never extend true acceptance,” the writer Samuel Kassow stated in 2007 in his book, Who Will Write Our History?: Emanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive, which contains the most comprehensive examination of Szlengel to date.

Szlengel’s poetry first appeared in Nasz Przeglad in 1937. While Louis’ victory over Schmeling the following year encouraged him momentarily, his other poems from that time, when Hitler threatened Europe with war, were filled with foreboding. In “Do Not Buy New Calendars,” written in January 1938, he wrote of his reluctance to tear off any pages, for fear of what might lie underneath.

I stare at the pages like at the blind fates.

Fear and dread are weighing me down.

This calendar is hiding thousands of cables,

Alarms from near and far.

A year later, in “The Frightened Generation,” those alarms had only intensified.

Will there grow a generation of frightened people

Whom every rustle would wake at night,

A clatter on the stairs, sound of a stranger’s voice

Would throw them into swells of panic and chaos,

People who lock their doors, ready to jump

When they hear someone is touching the door handle?

In September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and in November 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was sealed. Szlengel was among the nearly 400,000 Jews inside. Later, still more Jews from other communities joined them. He continued to write, now for the ghetto’s largest nightclub—even the doomed need distractions—known as “Café Sztuka,” or “Art Café.” It was a bizarre version of New York’s café society, catering to intellectuals in search of sophisticated fun, where various actors and musicians performed songs and sketches. The hero of the film The Pianist, Władysław Szpilman, sometimes played there. Szlengel’s entertainments, called “A Living Newspaper,” were the ghetto’s equivalent of the Daily Show: Topical takeoffs on the Nazis, on Jewish machers, and other risible realities behind the walls.

The satire was, of course, short-lived. In July 1942, the ghetto was thrown into panic as the Germans began shoving Jews by the tens of thousands on trains bound for Treblinka, 60 miles to the northeast. For a time, until it became morally unacceptable to him, Szlengel had belonged to the ghetto’s Jewish police force. Then, assigned to work in a brush factory, he continued to be spared the fate of so many of the others. But it took time to liquidate the ghetto, and for thousands of others, life went on. Szlengel kept writing his poems, first by hand, then typing them on carbon paper, so that they could circulate more easily. Often, he read them aloud to groups of Jewish factory workers. Others would copy and then recopy them: The grammatically incorrect Polish on some versions, Kassow notes, indicates that for some of those circulating them, Polish was not their native tongue. As conditions became more desperate, the impact of the poems grew. Emanuel Ringelblum, the historian who led the massive effort to chronicle ghetto life by stashing away documents in cans he hoped would be unearthed after the war, called Szlengel “the poet of the Ghetto.”

Possibly because of his ties to the ghetto police, Szlengel never participated in, nor presumably even knew about, Oyneg Shabes, Ringelblum’s highly clandestine operation. Ringelblum evinced a certain disdain toward Szlengel’s poems, describing them as “artistically mediocre.” But Szlengel was among the luminaries Ringelblum profiled, and his poems were among the documents he and his 60 associates took pains to preserve. Ringelblum explained why: They “moved those who heard them to tears because they were topical, on problems that the Jews lived with and felt,” he wrote. Though theirs were very different tools, Szlengel and Ringelblum were in fact engaged in precisely the same work: creating a contemporaneous account of Warsaw Jewry’s final days, one that would stand up against the revisionists who would inevitably arise one day to say that their catastrophe was simply too fantastic to be believed. Their works are wonderfully complementary, for it is at their respective ends of the written spectrum—the one broad and detailed and hyper-literal, the other personalized and idiosyncratic and distilled—that the most irrefutable evidence may be found.

Continue reading: 1942, other fantasies, and “A Window to the Other Side.” Or view as a single page.

Between July and September 1942, more than a quarter million Jews in Warsaw were deported to Treblinka. Sometime late that year, Szlengel assembled his poems, alternately poignant, outraged, anguished, and defiant, into a collection he titled A Cry in the Night, and smuggled it to a friend on Warsaw’s “Aryan” side. In an introduction he wrote

These poems, written between two upheavals,

Between the end of July and September

Nineteen forty-two,

Shortly before the destruction

Of the largest Jewish community in Europe,

Are dedicated to those who gave me heart

In times of all-consuming chaos,

Who, within the whirlpool of events,

The random, dance-like ritual of death,

Cared not for money or even themselves,

But for the last of the Mohicans,

Whose entire wealth and only weapon

Were words.

Some of his verses, presumably written in the ghetto’s early days, are almost unbearably sad. In “The Telephone,” Szlengel is at work, sitting by a phone—which, remarkably enough, remains connected. He longs to call someone outside the ghetto, only to realize that there is no one left to call: He and his gentile friends had taken separate paths once the walls went up. So, he dials the number Warsaw residents always called to get the time, wondering if its recorded voice, at least, remembers him. And she does, or appears to: 10:53 p.m., she tells him cheerily. Then, as she ticks off the minutes in the background, more than an hour’s worth of them, Szlengel summons up his former life in free, urbane, prewar Warsaw—watching Gary Cooper at a local movie theater, passing newsstands and neon lights and tramcars and sausage vendors, looking on as young lovers walk arm-in-arm along Nowy Swiat. And as his mind wanders through that world, tantalizingly near yet utterly inaccessible, he continues to listen gratefully to the pleasant-sounding woman at the other end of the line.

How nice to talk like this

With someone–no fuss, no pain …

You’re so much nicer than

The lovely women I’ve known.

I feel much better now–

There’s someone over there,

Someone who listens even though

He belongs to the other side.

Keep well, my faithful friend,

There are hearts that do not die.

Five to twelve–you say.

Yes, it’s late. Goodnight. Goodbye.

Similarly, in “A Window to the Other Side,” he stares out of his factory—itself an offense punishable by death—onto the Krasinski Gardens, where until only recently old Jews had gone to argue and Jewish children could play without fear that the Polish children would bully them, and then beyond it to the magical, nocturnal city, bathed in moonlight.

Having thus seen enough

For days, and for tomorrow,

I raise my magic arms:

Speak up, Warsaw. I’m here.

And lo … a thousand pianos

Open their stagnant lids,

And as if ordered, rise,

Heavy, resigned, and sad …

A Chopin polonaise

Flows from a thousand keys,

Into the tortured night

Notes fly like hungry birds …

Enough … I drop my arms.

The polonaise is done.

I turn again within.

There is no outside.

He has other fantasies. In one, Nazi guards look on aghast as Szlengel wanders up to the ghetto wall in a top hat and tails. In another, he dreams of liberation, when women will again wear lipstick and mascara. And of an assignation with someone else’s wife—though Szlengel was married, he rarely writes about his own—in which, at the moment their lips touch, all the bullets and grenades in the world suddenly hang motionless, the ghetto factories stop production, the informers cease to inform. In yet another, he ponders the new Jewish holiday that one day will commemorate what they all were enduring, during which survivors will gather in cellars like the ones in which they hid, and pray and celebrate and weep while their children scoff at recollections which to them sound as preposterous as those tales of Moses parting the Red Sea. And when the holiday ends,

All of them, old and young, will come out

Into daylight, a better and new world

It will be safe and light.

Holy supper will be served—

With swastika and plentiful honey.

As the deportations began and accelerated, such flights of fancy largely cease, and the mood turns sepulchral, infuriated, fatalistic. “The Monument” is a tribute to a very ordinary woman (“Was she good? Not very/ She was often quarrelsome and moody”) deported to her death, whose husband and son come home one evening to find only her parting gift: a cold pot on the stove. “Things” traces how the Jews’ inventory of possessions diminishes as they move to ever-smaller quarters, until, embarked upon on the “Jewish road”—aboard the trains to Treblinka—they own only water and cyanide. In “Janusz Korczak: A Report,” he watches the famous leader of Warsaw’s Jewish orphanage escort his children—“Washed and neatly dressed/ As for a Sunday stroll in the park”—to the Umschlagplatz. And he wrote about where they, and everyone else, were destined.

The journey lasts, sometimes

Five hours and 45 minutes,

But sometimes it lasts

A lifetime until death.

The station is tiny.

Three fir trees grow there.

The sign is ordinary:

It’s the Treblinka station.

No cashier’s window,

No porter in view,

No return tickets,

Not even for a million.

There, no one is waiting

And no one waves a kerchief,

And only silence hovers,

Deaf emptiness greets you.

Only an old poster

With fading letters

Advises:

“Cook with gas.”

Continue reading: “This is our history,” Jewish resistance, and the real target of his ire. Or view as a single page.

For all his love of Poland, Szlengel did not spare the Poles. In a poem called “The Key at the Concierge,” he attacked those who served the Germans and plundered Jewish property. (He deliberately omitted this poem from his collection, at least, he wrote, until the passions the war had inflamed had subsided.) Nor did he exempt the Jews, particularly those pampered, indifferent Jews living blithely abroad, drinking orange juice every day as their European brethren were exterminated. In one poem, he writes of a mythical Jewish company in New York making a killing on the Yahrzeit candles that commemorate them.

But the real target of his ire is God. In one poem, he portrays him as a benevolent, clueless elderly man, exempted from wearing the ubiquitous Jewish armband and carrying a precious Uruguayan passport. In another, he castigates him for relegating his faithful flock to nooses and ditches and gas chambers, insisting that he won’t get away with it. God is in the dock, his “Chosen People” are the prosecutors, and his sentence is to share their fate.

And when the killers will have pushed you and forced you

And dragged, stuffed you into the steam chamber

And sealed the hatch behind you

The hot steam will begin to suffocate you, to suffocate you

And you will scream, you will try to run—

And after the torture of dying will have stopped

Then they will drag you out and throw you in a horrible pit

They will put your stars out—the gold teeth in your jaw—

And will turn you into ashes.

In an essay he called “What I Read to the Dead,” written as the ghetto’s numbers continued to dwindle in early 1943, Szlengel compared himself to the last man alive on a doomed submarine he’d seen once in a Soviet film, who scratched a final message to posterity as he gasped for breath. As all those with whom he’d performed, and those who listened to his poems, and all his neighbors and friends—each of them, as he put it, a co-author—were carted away, he, too, was suffocating.

“They will not be mentioned in any statistics, no memory of them will remain,” he predicted. “But for me these were living people, close to me, touchable. Their fate touches me more than the fate of Europe.” On an unseasonably warm February day in 1943, Szlengel looked through his poems. “I have read those verses to warm, living people,” he wrote. “People who believed in survival, in liberation, in tomorrow, in revenge, in joy, in reconstruction. Please read them. This is our history. This is what I read to those who died.”

His despair lifted briefly when the first Jewish resistance began. Suddenly, those Jews who’d shuffled off under the watchful eyes of dapper, vain, and sadistic Nazi soldiers were fighting back. Finally, the cattle had arisen; finally, the Germans knew fear. That prompted Szlengel’s most famous poem, “The Counterattack,” a work that exists in several versions, probably because it was often recited from memory.

We beg you, God, for a bloody battle,

We beg you for a violent death.

Let not our eyes, before they close,

See how the train drags, drags …

But Lord, make our hands hit the mark,

So that the steel-blue uniform reddens with blood.

His wishes were fulfilled that April, when the ghetto uprising began in earnest. Szlengel fought with the only weapon at his disposal, setting down what he saw. What then happened to him isn’t precisely clear.

“Yesterday evening, the poet continued to write his poems in which he sang of the heroism of the Jewish fighters and lamented the fate of the Jews,” another ghetto resident, Leon Naiberg, wrote in his diary on May 8, 1943. “This would be the last time, since the bunker belonging to Shimen Katz [where Szlengel was hiding] on Shvientoyreske 36, collapsed onto itself.” But another account has Szlengel apprehended, then marched off along with everyone else to the Umschlagplatz. He, too, then, may have wound up at Treblinka, his ashes mixed with his readers’.

Szlengel himself was gone, as was whatever he wrote in those final few weeks, but some of his other poems survived: those he’d handed off to his friend, those Ringelblum had preserved and would unearth after the war, still others he’d apparently stuffed into an old desk, to be retrieved 15 years later when the man who’d inherited it chopped it up for firewood. Some were published in Poland immediately after the war, but for many years they remained in a ghetto of their own, the victim of the language in which they’d been born.

“If he had written in Hebrew or Yiddish or German, he would be known,” said Henryk Grynberg, a Polish-born writer and scholar who first wrote about Szlengel in 1979. “The feeling is, ‘A Jew who writes in Polish is not a real Jew, so why should we support him?’ ” Grynberg has translated some of Szlengel’s work, as have Pawel Mayewski, Michael Steinlauf, Maria Lewitt, and Kassow himself, but few of those poems have migrated beyond the Internet. (The bulk of the translations in this essay come courtesy of Yala Korwin, a New York poet and visual artist who is originally from Lvov.) No volume of Szlengel’s poems in English exists.

In Hebrew, it’s different, thanks to Birenbaum. She settled in Israel after the war and for four decades believed that she was the only person alive who even remembered Szlengel’s words. Entirely by chance, someone on a kibbutz gave her the Polish edition of his poems. She pored over the slim volume; one after another, the words she’d memorized re-materialized before her—like dear friends she hadn’t seen for years, she wrote, or homes in which she’d once lived. She translated them and, in 1986, published them at her own expense. One was adapted by her son, Yaacov Gilad, for a song sung by the popular Israeli rock star Yehuda Poliker. Szlengel’s poetry has also become better-known in Poland, and there is now even a short entry on him in the Polish Wikipedia.

Szlengel’s paean to Joe Louis was neither his best nor his most prophetic work: The Brown Shirts emerged from that fight at Yankee Stadium in June 1938 as unscathed as the Brown Bomber. In light of what was to come, in fact, the poem seems poignantly naïve. Still, through it Szlengel had demonstrated far more graphically than I could have ever hoped something I’d been eager to prove, and I was in his debt. And when I set out to discharge that debt, I stumbled upon all these other, far more powerful and important poems. Forgotten they may be, but with them he gave me, and all of us, an even greater gift.

David Margolick, a Vanity Fair contributing editor, is the author of the upcoming Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock, scheduled for publication in October by Yale University Press, as well as Show of Shows, coming soon from Nextbook Press.

David Margolick, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, is writing a book for Nextbook on Your Show of Shows. He’d appreciate hearing from those with memories or comments on the program: [email protected].