Lou Reed, Poet

The new volume ‘Do Angels Need Haircuts?’ brings to life a historic 1971 poetry reading, recorded and recently rediscovered in the late musician’s archives

What do you do after recording a string of brilliant art-rock albums, at the height of your rock ’n’ roll notoriety and New York hipness? If you’re only 29 and are already admired by some of the greatest contemporary artists? You quit it all, and assume your vocation as a poet, of course.

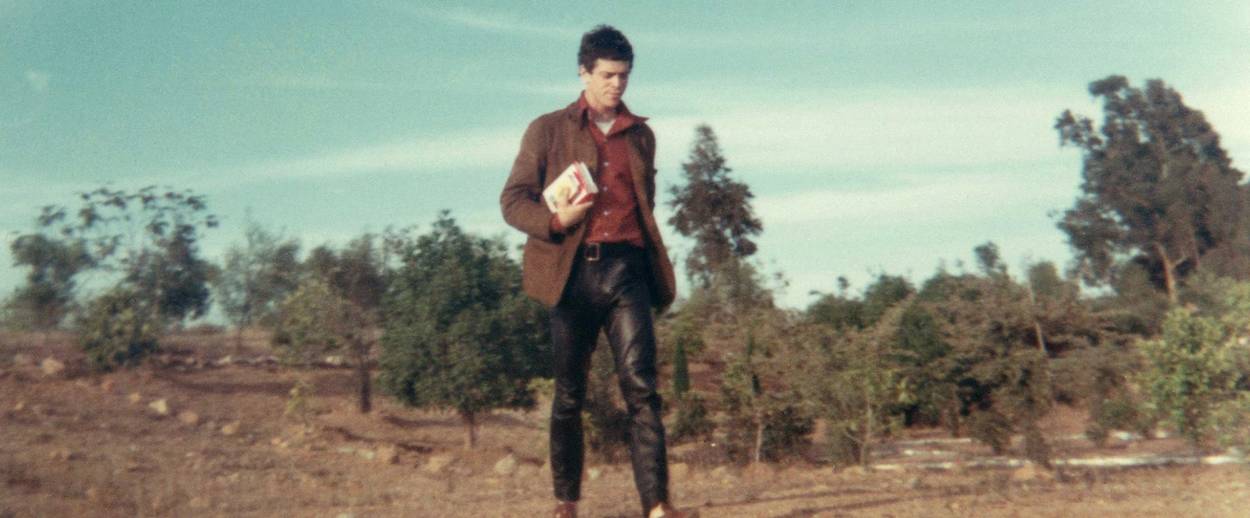

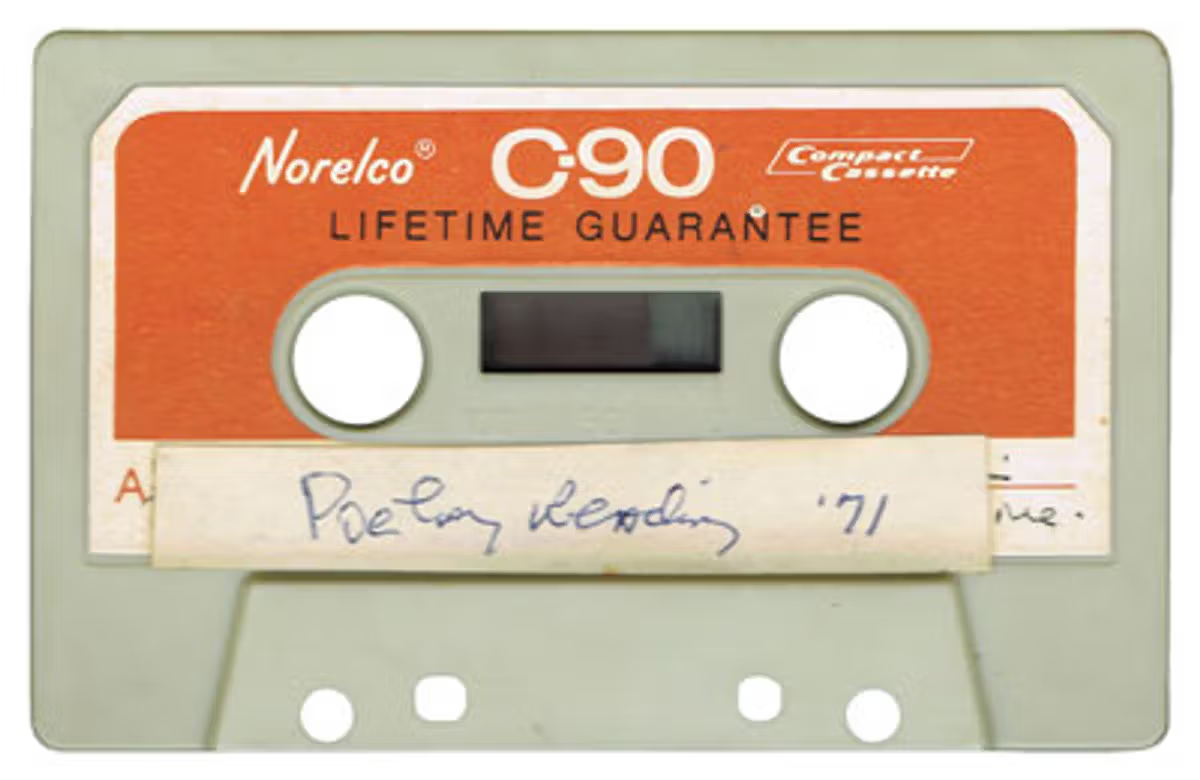

That, anyway, was Lou Reed’s thinking in 1971, shortly after leaving the Velvet Underground—the band that was later hailed as visionary not only for its forays into rock, proto-punk, avant-garde, noise, and folk—but also, for Reed’s daring, controversial, and complex lyrics. On March 10, 1971, at the St. Marks Poetry Project, Reed announced his desire to abandon the music world and dedicate himself to poetry. He read a set of poems and lyrics to a packed, enthusiastic house that included some of the heavyweight poetry legends of the time. As the reading started, Reed turned on the tape recorder. The recording of that reading, on a cassette tape, was stored in Reed’s archives for decades, and discovered only after his passing, by the artist’s archivists Jason Stern and Don Flemming.

Do Angels Need Haircuts?, a handsome volume released by Anthology Editions this week, brings together the story of this historic poetry reading along with poems read by Reed, photographs, and a 7-inch vinyl excerpt from the recording. What emerges is more than a story of an artistic detour in the career of a recording musician: it is a glimpse into a more personal, vulnerable, and yet gregarious and experimental Lou Reed.

The reading marks a great convergence of poetry and music, intellectual/literary world and street culture. Anne Waldman—one of our greatest living poets, who directed The Poetry Project for many years, and was responsible for inviting Reed to perform—recalls the evening in the introduction to the book: “the night for Lou was revelatory, his own intervention. He had been anointed with the higher command of Poetry.” One can distinctly feel the “anointment” in this striking opening manifesto:

WE ARE THE PEOPLE

We are the people without land. We are the people without

tradition. We are the people who do not know how to die peace-

fully and at ease. We are the thoughts of sorrows. Endings of

tomorrows. We are the wisps of rulers and the jokers of kings.

Who is the “we” Lou Reed is talking about? Sure, this could be about America, as undoubtedly, he is alluding to the opening sentence of the Constitution. Just as well, with its references to nomads and endless travails, it’s hard not to think of this as a secular, diasporic Jewish manifesto (the artist’s father was born Sydney Rabinowitz, but Americanized the family name to Reed). At the same time, the poem could be describing the ingathering of artists who then flocked to New York. Reed’s wife, Laurie Anderson—the legendary avant-garde poet, musician, and performance artist—recalls in her afterword to the book: “Young artists in New York in 1971 had come from all over the country. They had come from all sorts of suburban, ‘normal’ places. The way kids who wanted to be actors went to Hollywood, kids who wanted to be poets, musicians, and artists found New York. They came alone; it wasn’t the kind of thing you did as a group. You met your group there. Your real family.”

Though the opening images of the poem are seemingly straightforward, even anthemic, “We Are The People” quickly turns surreal: “We are the thoughts of sorrows.” Notice that Reed does not describe himself and his people as those who possess sorrowful thoughts—he suggests that he actually is one of those thoughts. A human being as a metaphor for a thought? Is the poem talking about the way we conceptualize others, choosing some to represent the nexus of our own sadness? Or is this a vision of the world as a living being, in which certain artists represent those reflective, reluctant thoughts? The poet Amiri Baraka once wrote: “Thought has a self. That self is music.” It seems that the mysterious relationship between music and consciousness is what Reed was getting at.

The poem continues, alternating between clarity and surrealism: “We are the people without a country, a voice, or a mirror. We are the crystal gaze returned through the density and immensity of a berserk nation… We are the people without sorrow who have moved beyond national pride and indifference to a parody of instinct.” The poet is not interested in an attempt to find a middle ground between nationalism and apathy—he’s after the “parody of instinct,” the kind of art, which is, at the same time, a form of critique. The phrase is also, perhaps, Reed’s meta-poetic commentary: he is of the people, who parody the instinct of self-definition and so, instead of writing a straightforward manifesto, he constantly veers off into abstraction.

One of the greatest things about the book is that it preserves not only the poems but also the chatter between them. Anderson calls these snippets “Avant-garde stand-up … parallel poems.” Before reciting one of the poems, Reed quips, “This is called ‘Force It.’ Not a faucet, but ‘Force It.’ ” Commenting on his poem “Lipstick”: “This is because I always wished somebody made black lipstick and then I saw a friend of mine that wore it and I said, ‘Where’d you get it?’ and they said, ‘Oh man, everybody’s wearing it.’ I said, ‘I thought I came up with something new.’ They said, ‘No, man.’ ”

The book also includes a scan of a typed letter addressed the to poet and writer Delmore Schwartz, who was Reed’s English professor and mentor at Syracuse University. Reed writes, as it appears with typos: “I decided that I’m very very good and could be a good writer if i work and work. i know that’swhat i’ve got to do, no getting around it.” This letter dates back to 1965, and is proof that a poetic career had been on Reed’s mind before, and that Schwartz had a great deal to do with this aspiration. Reed recalls Schwartz in his prose poem Spirited Leaves in Autumn:

I’ll haunt you if you quit, he warned me, playing Bloom to my Dedalus one drunken, reeling night in college. Five vermouths at once because the waitress took so long. Was I always in dishonor? NO, cries Delmore now Joyce. You’re the sickness same inside a writer and then home to Liz to read Finnegans Wake aloud.

Alluding to Joyce’s Ulysses, Reed hints at the quasi-paternal role Schwartz took in Reed’s life. (Reed’s own father was a Long Island accountant.) Grammar seems to tear at the seams in this piece, and at the end of the quoted passage it is no longer clear who is drinking the vermouths, and who is heading home to read Finnegans Wake—the poet and his mentor are enmeshed. The “sickness” transmitted from Joyce to Schwartz to Reed may be the dark side of the artistic genius—self-destruction. The poem is a gritty and wise elegy, and at the same time, is an acknowledgement of Reed’s formative artistic beginnings. It is what Anderson means when she pithily describes Reed’s poetry as “Warhol meets Shakespeare”. And though admittedly, not every piece in the collection lives up to that description, the sentiment captures the poet’s straddling the hip and the eternal.

Reed’s poems and spoken word pieces had a direct affect on the work of Talking Head’s David Byrne, who often cited Reed as his influence, and Patti Smith, who can still sometimes be spotted at The Poetry Project. On the night of the 1971 poetry reading, 22-year-old, barely-known poet Jim Carroll opened for Reed. Less than a decade later, Carroll released a track that became a punk-poetry anthem, “People Who Died.”

Reading Do Angels Need Haircuts?, one may wonder why Reed did not become a poet. Anne Waldman offers one possible explanation: “Unadorned poetry was perhaps too limited a form for all his theater of voices.” Indeed, Reed’s poetic brilliance was not so much in the craft of each individual written word, but rather in the intonation and timing. Think, for example, of the Velvet’s Underground’s iconic hit, “Sweet Jane”:

Some people, they like to go out dancing

Other peoples, they have to work

Just watch me now

And there’s some evil mothers

Well, they’re gonna tell you that everything is just dirt

You know, that women never really faint

And that villains always blink their eyes

And that, you know, children are the only ones who blush

And that life is just to die

On the page, these may seem like merely witty lines. But to hear Reed’s voice, dripping with that “parody of the instinct,” to experience the whole range of his “theater of voices,” is sublime. “Sweet Jane” is all about the music of the semi-spoken, conversational phrasing that feels utterly spontaneous, and is therefore both commonplace and yet somehow inimitable. Poet Louis Zukofsky famously suggested that poetry is “An integral / Lower limit speech / Upper limit music,” and I can think of few more apt examples than this song, where the highly colloquial everyday speech immediately soars into gorgeous music.

***

Celebrate National Poetry Month with Tablet’s deep archive of articles about poetry and poets.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).