The Very Jewish Love Story Behind Erich Segal’s ‘Love Story’

How the famed writer’s unrequited passion for Janet Sussman led to the era-defining best-seller, and how Segal, who died six years ago this week, never got over her

“What can you say about a 25-year-old girl who died?” reads the opening line of Erich Segal’s 1970 best-seller Love Story. Well, for starters, Jenny—or the real-life model for Segal’s fictional tragic heroine—didn’t die. Her name is Janet, she’s Jewish, and she’s alive and well and living in New York City.

In 1998, a series of misreported conversations made it sound as if Al Gore had claimed that he and then-wife Tipper had inspired the young couple at the center of Love Story: the preppy Oliver Barrett IV, and working-class ingénue, Jennifer Cavilleri. A woman named Janet Sussman stepped forward as the “real” Jenny, which was a revelation of such proportions that Maureen Dowd wrote about it in her column for the New York Times, People Magazine ran a feature story, Inside Edition interviewed her, and Oprah later followed up with a taped special segment. But these quick takes only scratched the surface of what turns out to be a more revealing—and very Jewish—story, involving a youthful love triangle in Midwood and an author who would transform unrequited love into a book that made him rich and famous.

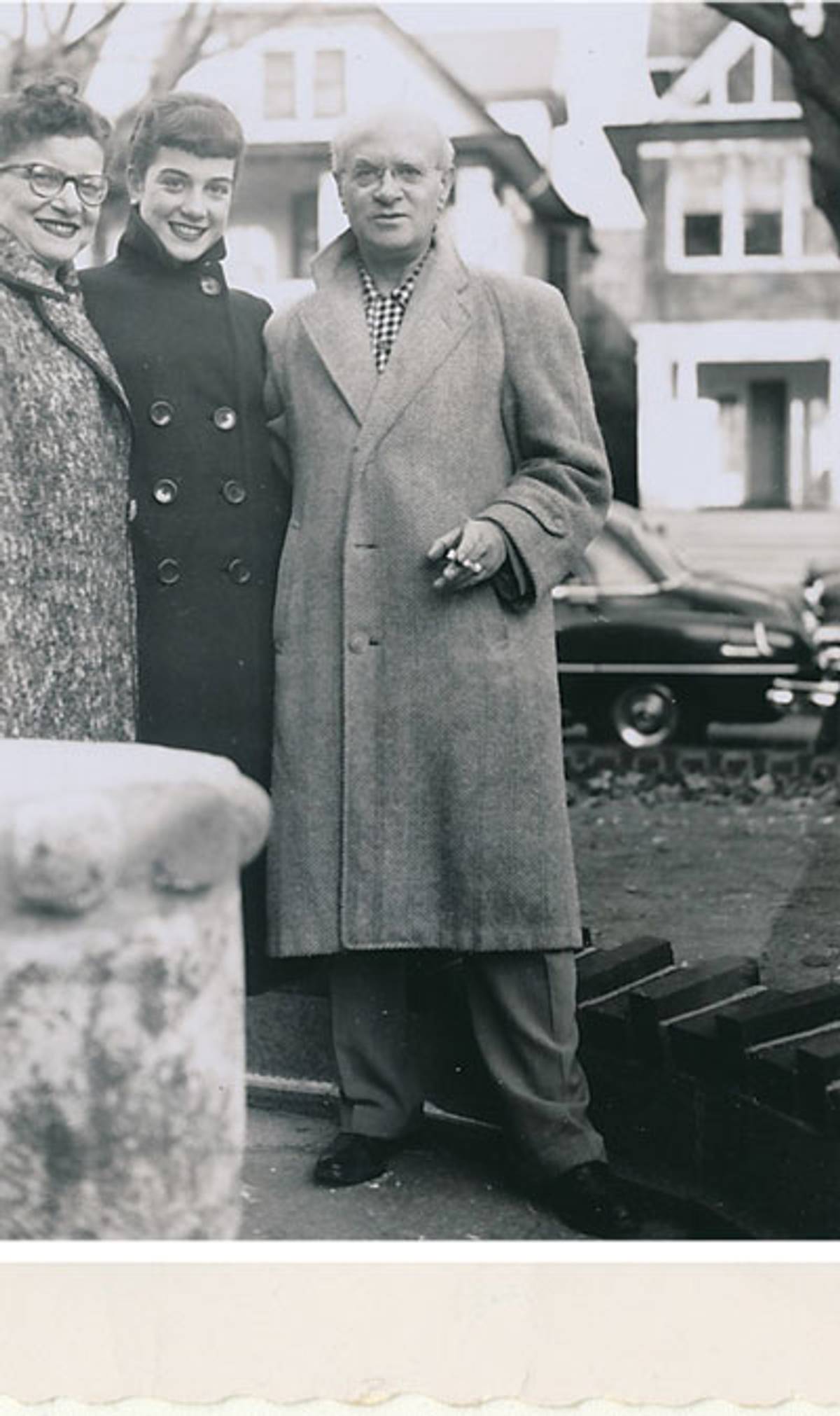

Janet Sussman grew up in Flatbush, the younger daughter of intellectual Russian-Polish immigrants who came to the United States with the help of Zionist organizations. The family was part of what her older sister Deborah called “the Tribe,” a close-knit social circle dedicated to raising money to help establish a Jewish homeland. That circle included the Gartners, the parents of a boy named Gideon, with whom Janet shared the same piano teacher, Roberta Berlin. From the time they were “eight, nine, ten years old, we were performing together in recitals playing four-hand piano duets,” Janet recalled, when I spoke with her recently.

Around the same time, she started attending Camp Kinderwelt (Yiddish for “children’s world”), a sleep-away summer camp for boys and girls aged six to fifteen located in Highland Mills, New York. It operated in tandem with Unser Camp (“our camp”), a resort that attracted Yiddish intellectuals and artists—theater actors, directors, poets, and teachers. Established in the late 1920s, Kinderwelt accommodated about 500 campers and counselors at its height. All that remains of Kinderwelt today is a website run by Suzanne Pulier, who was a camper in the late 1940 and ’50s at the same time as Janet. Suzanne recalls that Janet’s nickname was “Machine-Gun.” Suzanne explains: “Apparently she had a laugh that sounded like that and was very contagious. I know many a boy had a big crush on her!”

Suzanne’s memories concur with those of Marty “Smitty” Smith, who remembers Janet as being “very pretty, part of the ‘with-it’ group,” who sang for Saturday services and Friday night Shabbat. Suzanne clarifies: “We sometimes performed in Yiddish for the Unser Camp adults, we walked through their camp on Shabbat showing off our white clothes for the evening’s religious services and we sang for the adults when they had events in the Literashe Vinkel (the little amphitheater).” Janet also played the piano to accompany the singing.

In 1952, while at camp, 15-year-old Janet received an unexpected love letter from a 17-year-old schoolmate in Brooklyn. It was a seven-page confession that he loved her with all the force a love-struck teenager could muster. He felt compelled to write because he was about to leave for college, and feared he’d lost his chance to go on a date with her. He dreamed they would get married in ten years. He dreamed that she would just write back. He worried that he was foolish to confess, because so many other guys were also in love with her.

***

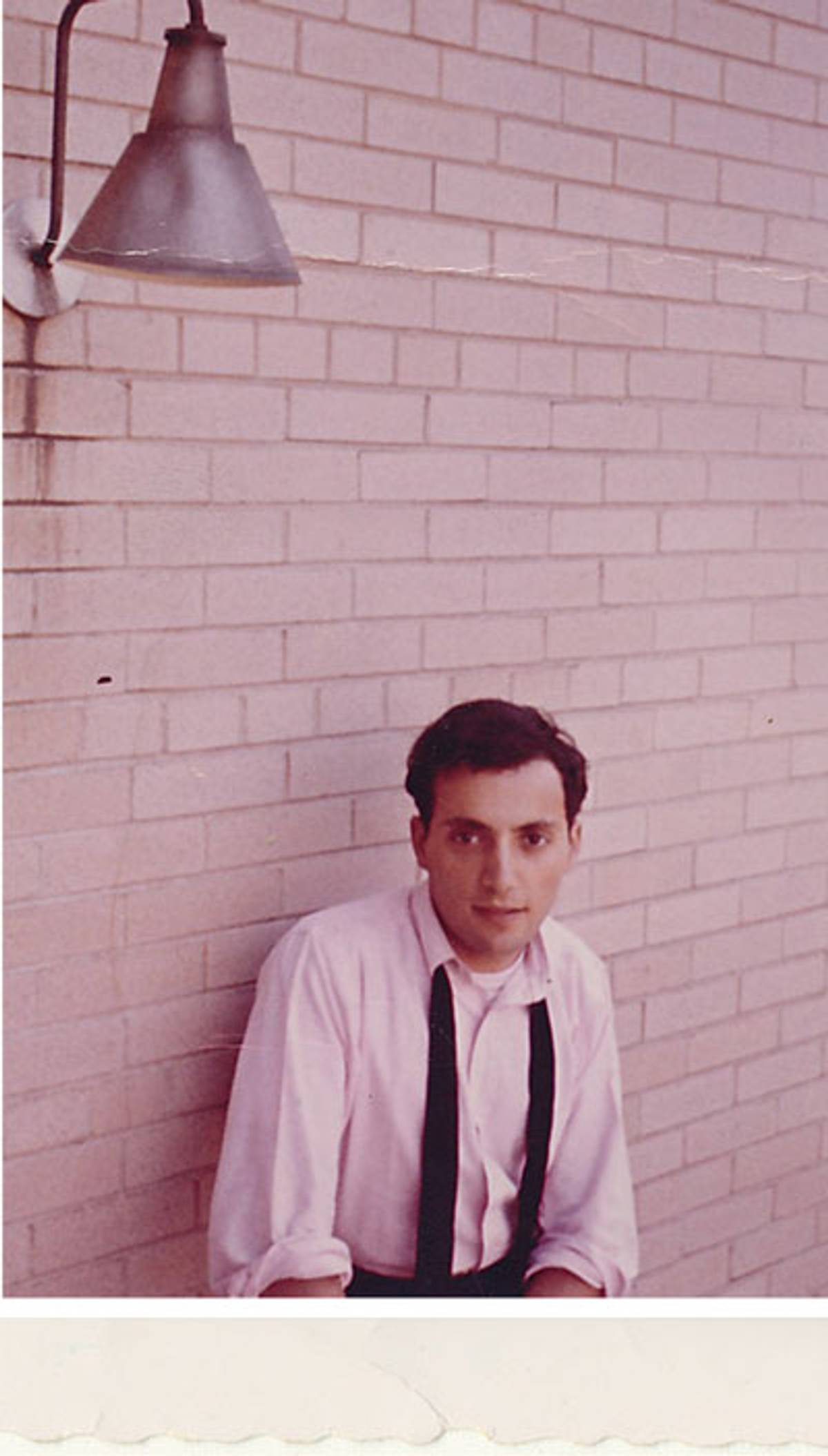

In the early 1950s, Janet Sussman attended Midwood High School along with Gideon Gartner and Erich Segal. (Allan Konigsberg, class of ’53, was at Midwood with them too. He would later become known as Woody Allen.) Erich was the same age as Janet but a grade ahead of her, and Gideon, who wrote her the seven-page love letter, was two years older but three grades ahead. Inside the social ecology of Midwood High, there was very little overlap between Erich and Gideon, and no points of intersection between Janet and Erich.

Now an undergraduate at M.I.T., Gideon was always calling her, trying to get her to go out with him. When that failed, he began writing her letters. But Janet was not interested in him. “I had work to do!” Janet exclaims in tones of mild indignation. She was too busy with friends, singing, and her studies to bother with a boyfriend. With lifelong best friend Helen Mones, Janet would play guitars once a week; they also sang together in the All-City Chorus, which brought together students from all five boroughs.

So, when Janet began receiving more anonymous valentines, she didn’t think anything of it. “In those days,” she explains, “life was what happened. You didn’t question things. I got letters. I figured that everybody got letters.” The letters started in 1954, when she was 17 years old, and a junior in high school. “And then he started to sign his letters to me,” Janet says. The new letter-writer, Erich Segal, would keep writing her letters for the next 16 years.

Janet knew who Erich was, of course. Everybody knew him as the Mayor of Midwood, the equivalent of the student body president. But she had no idea how she came to his attention. He didn’t hang out by her locker or participate in chorus. She didn’t see him at all during her normal daily routines.

Unbeknownst to Janet at the time, Erich had asked Dick Kolbert to find out about her. Dick was class of ’55, a junior, and into basketball. Erich was class of ’54, a senior, a star of track and field. Dick sat next to Janet in English class and had played Algernon to her Cecily in the student production of Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest. Dick’s secret assignment was to “ask her questions, find out if she had a boyfriend, what she said about him, that sort of thing,” and to report back to Erich what he’d learned. “It became clear that Erich was stuck on Janet,” Dick says crisply, “and Janet did not reciprocate.”

The following year, “Old Kolbert” succeeded Erich as Mayor of Midwood. A dignified man who speaks carefully, Dick doesn’t doubt that Erich based “Jenny” on Janet. There were too many similarities between them. And he believes that Erich’s feelings were sincere. “Teenagers really do experience genuine love,” he muses. “Even if it’s love at a distance. He may have been a little self-dramatizing, but he was genuinely smitten.” Though he wouldn’t reveal any details, Dick confirmed that Erich subsequently wrote “a long letter to him, pouring out his heart” regarding the depths of his feelings for Janet and asked him to burn it after reading. And so he did.

***

Dick Kolbert remembers that Janet was very pretty, but that it was Marge Cama who was voted “Prettiest Girl” in their graduating class at Midwood. The difference was that Janet had, “well … something,” he offered vaguely. “If there was a Geiger counter, she would be towards the top.”

Teenage boys may have been drawn to Janet’s artless good looks, but it was that ineffable quality of being your own person that made them fall in love with her. When Janet’s sister Deborah was 14, she wrote a strangely revealing essay about her then 8-year-old sibling. “Her tiny pug nose and tinkling laugh are two of the factors which gave her the titles, ‘Mis-Chief’ and ‘Machine-Gun,’ ” Deborah wrote of her sister in third grade. “I often wonder how she acts with male friends of her own age, and why they are so attached to her.”

Deborah titled the English-class essay “A Female Casanova” on account of the fact that Janet had a “boyfriend”–another third-grader named Ronald, who briefly became sick and stayed at home, leaving room for “Richard” to move in. Yet Deborah was perplexed. What qualities did Janet possess that made boys become infatuated with her? Nobody I spoke to about Janet’s years at Camp Kinderwelt or Midwood High School described her as a flirt, “boy crazy,” or any variation thereof. Rather, her response to male attention seems consistently to have been amused bafflement, followed by indifference.

In high school, Janet shared Erich’s letters with her other life-long best friend, Diana Stone. Diana lived across the street from the Sussmans’ home in Brooklyn, and she and Janet were as close as sisters. With a note of incredulity in her voice, Janet exclaims: “I think Diana even tried to persuade me to relent, just a little!” To no avail. She wasn’t rude to Erich, Janet stresses. But she never went out with him. Yet Erich’s letters kept coming.

At Barnard, Janet double-majored in music and French. An accomplished pianist, she composed the entrance music to Barnard’s “Greek Games” as well as a second piece for the dance portion, choreographed by Tobi Bernstein (today the distinguished dance critic Tobi Tobias). “This piece became the soundtrack to our childhood,” Janet’s youngest child, Aleba, states, “as it was the one piece she would turn to again and again when playing the piano for pleasure and not for work. We loved it so much—it totally captures her passion. It has very intricate syncopation amid gorgeous melodies.” A serious student, Janet took a composition class with Otto Luening across the street at Columbia University. This very small class included two future winners of the Pulitzer Prize for music composition: John Corigliano, who was also in Janet’s class at Midwood High School; and Charles Wuorinen, who “sat in the back row alone all the time,” Janet elaborates. “We all knew he was the genius of geniuses.”

By fall of 1959, she had graduated from college and finished up a summer at the Cummington School of the Arts in Massachusetts. She then found a job working as an administrative assistant for Columbia Records in New York City. Meanwhile, her older sister Deborah, a protégée of Ray and Charles Eames, had been on a Fulbright year in Ulm, Germany, and had moved on to Paris, where she settled into her new job as a graphic designer for chic department store Galeries Lafayette. Deborah wanted her baby sister to come visit.

It was time for Janet to make a choice. She had a good entry-level job at a business where she might have a future if she stayed—but Paris beckoned. After hemming and hawing, she finally gave notice to her bosses at Columbia Records and joined her sibling for a stint of seven months in Europe. On June 8, 1960, Deborah wrote to their parents:

after five weeks, i cannot imagine being without her. i was amazed and impressed, and so are others, at her insights and awarenesses of people. she has developed very highly intellectually, equaled (need one say?) by her beauty. yet i think that being far from home and her usual routines is the best thing she could do right now, in order to learn a certain independence.

Deborah’s letter made no mention of the man from Midwood High who was planning on delivering himself to their doorstep in the 18th arondissement the very next day, flowers in hand, with plans to take her baby sister out for her birthday, which happened to be close enough to his birthday, too. Erich Segal and Janet were Geminis, the sign of the Twins, born one week apart: June 9 for her, and June 16 for him. Erich had written Janet to let her know of his plans, but he’d not heard from her in two weeks since his last letter, he complained, and had no idea if she would be there when he arrived.

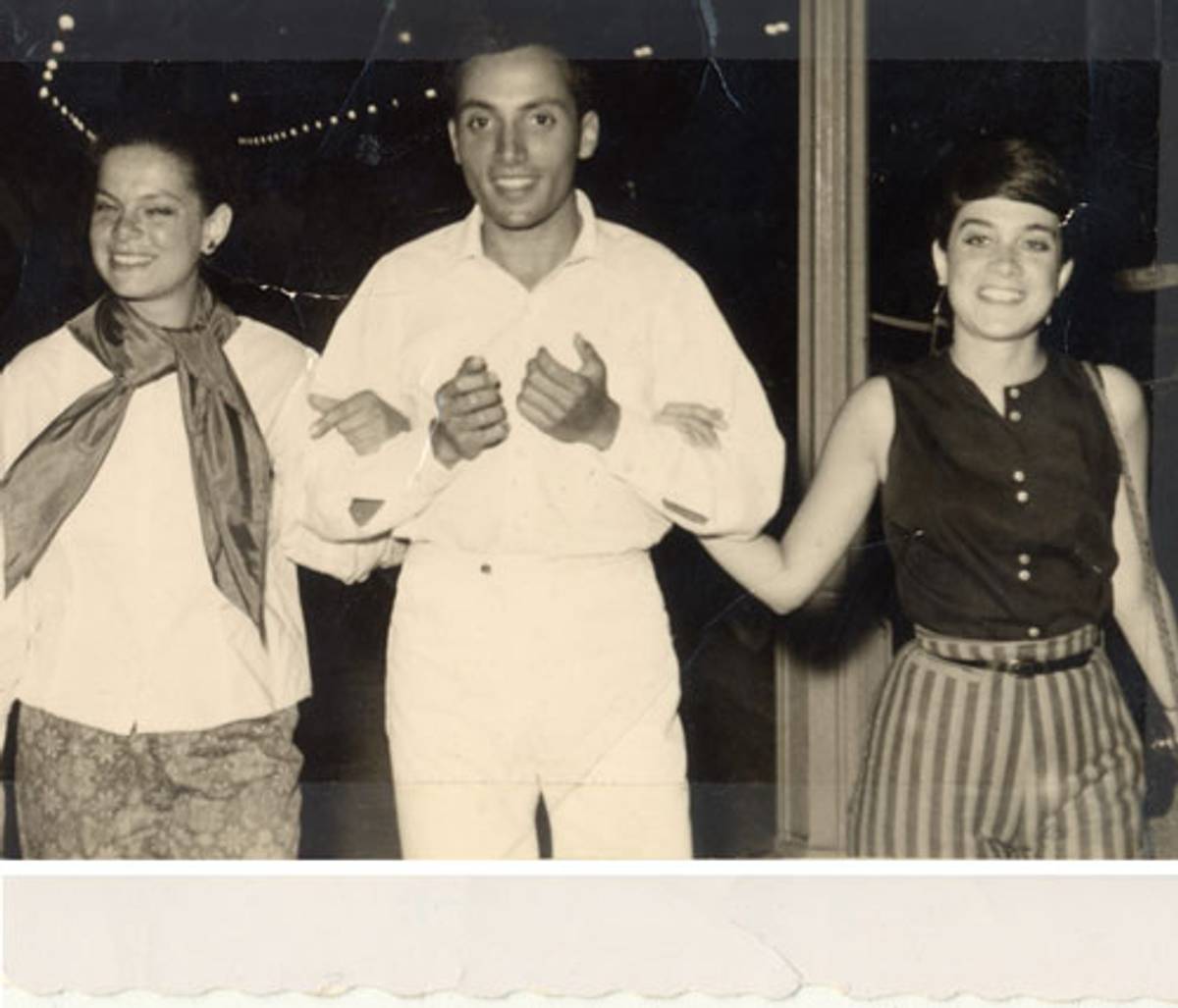

He had reason to fret. If Janet wasn’t exactly avoiding him, she wasn’t waiting breathlessly either. The sisters had driven to South of France, to the French Riviera, taking the routes favored by truck drivers because the food along the way was cheap and good. As for Erich, she says, he was “on his own.” It didn’t help his case that her sister “didn’t think he was important,” Janet relates with a rueful laugh. Ever decisive, Deborah summed Erich up and cut him down in three words: “He’s so short!” Janet concurs that he was short of stature, but with a “magnificent face.” When the three of them eventually ended up having dinner in Paris at the home of Erich’s aunt and uncle, “I was on good behavior,” Janet says lightly. “Deborah—ahem—wasn’t.” The formal meal turned into a scene from Hannah and Her Sisters à la française, with Janet being her charming and effervescent self, and Deborah blurting out caustic remarks in impeccable French.

That Janet agreed to dine with Erich’s relatives did not turn her into his girlfriend. “I wasn’t rude,” she exclaimed indignantly. “But he made every effort to see me, and I made none to see him.” Erich flew back to the United States, his love unrequited. And he kept sending her letters. From Cambridge, Massachusetts: a postcard mailed to her in Paris. From New York City: a telegram to her in Paris. From Barrow, Alaska: a letter addressed to her in Brooklyn. From somewhere over the friendly skies: a letter on American Airlines’ stationary, scrawled on a return flight from a Passover visit with his mother and family. From his office at Harvard University, where he’d obtained his undergraduate, Master’s, and doctoral degrees and then joined the faculty: a letter to her in Brooklyn, written in a ruled blue book used for exams. And so on.

Janet still has dozens of letters in her possession. They are full of chatty details of the non-events of the quotidian, using charming terms of endearment, little doodles, and clever puns in Latin, Greek, French, and Hebrew. During Janet’s sojourn in Paris, he visited her parents in Brooklyn. “Erich spoke Russian with my father, Polish to my mother, and Yiddish to my grandmother,” Janet recalls about that visit. Her parents approved of him, and they were thrilled when he told them he would be visiting her. From Paris, Erich sent a letter to Irving and Ruth Sussman to update them on the status of his visit with their daughters, including a description of that interesting supper with his relatives.

Following Erich’s departure from Paris, Janet had remained in France. She was nearing the end of her funds, so she began to look for a job. She found one close by in the 19th arondissement, working with a record company called Etablissements Atlas. Her job was to translate the French information on record labels into English. After two months, her bosses offered her a permanent position in London, where the company was opening a new office. But Janet didn’t take the London job, and she didn’t stay in Paris. Instead, both she and her sister decided to return permanently to the United States, sailing home on a ship called La Liberté. The voyage lasted a week. Upon their arrival, both sisters came back to the family home in Brooklyn, but Deborah immediately began readying to depart for California, where she would resume working for Ray and Charles Eames.

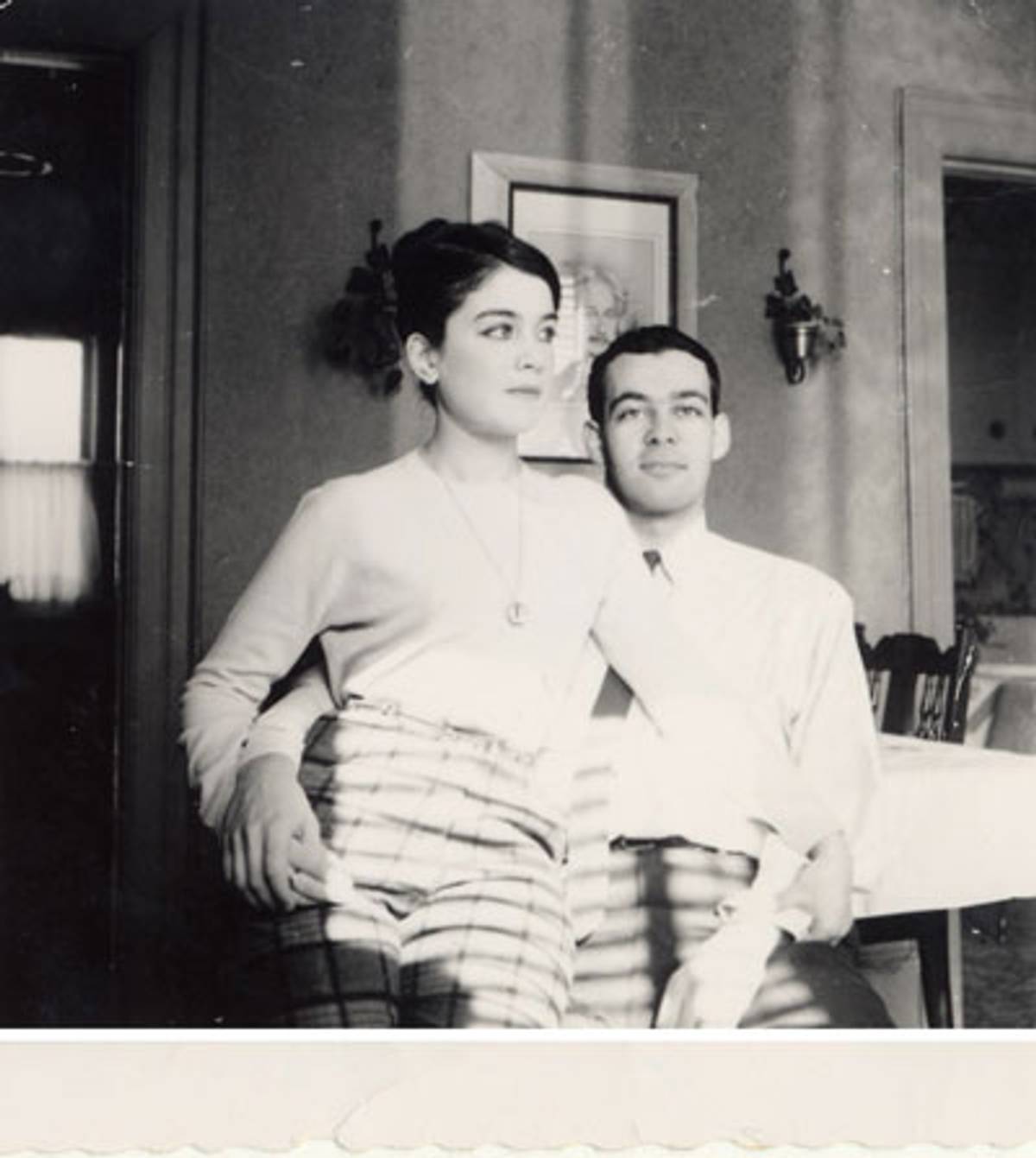

As it turned out, Erich Segal wasn’t the only suitor writing Janet earnest letters. Gideon was sending them too, and he had the home field advantage. “He was one of our own, part of the Rambam club,” Janet explained: “This was one of the arms of the Labor Zionist Federation, with the goal of establishing a nascent Israel. I inherited that fervor from my father.” And if, in high school, Gideon was a typical skinny teenager, Janet recalled, “he came back from college to Brooklyn, transformed.”

***

By October 1960, Janet had started a new job working as the assistant to Geraldine Souvaine, producer of the Metropolitan Opera’s Saturday Afternoon radio broadcasts. When Gideon called and asked her out again, her heart didn’t leap with giddy anticipation. Still, she accepted his invitation—in her mind, a kind of pro forma social ritual, the sort of meetup owed to someone whose parents knew your parents and participated in the same groups. “We’d never before been on a date. When he showed up, he was like a stranger,” Janet says in lingering tones of wonderment. “He was my piano partner but he’d been a boy, then. I came back from Europe and he was a man. I was suddenly romantically attracted to him. I admired his broad shoulders,” Janet laughed, a 78-year-old grandmother suddenly girlish again, “and that was it!” A few months after their first date, he and Janet married.

They’d planned a traditional big wedding in a synagogue, but Janet’s father Irving was hospitalized at Maimonides Hospital with a hip injury and suffering from what would later be diagnosed as the early stages of Parkinson’s. Janet related: “In the Jewish tradition, you don’t postpone the wedding, so we brought the wedding to him. The rabbi came, and the ceremony was held in the hospital. It was very small, just family and close friends. We left the next day for our honeymoon in Puerto Rico.”

It was a marriage between families, joined together inside a community that had supported them since they were small. They’d known each other nearly their entire lives yet had fallen in love as adults. By the time they wed, Janet’s childhood piano partner had pursued her for eight years, and it was the third time she’d resigned her job and walked away from a potential career. She was almost 24 years old.

Erich saw the wedding announcement in the paper and wrote Janet a letter to congratulate her. Still, his letters kept coming.

***

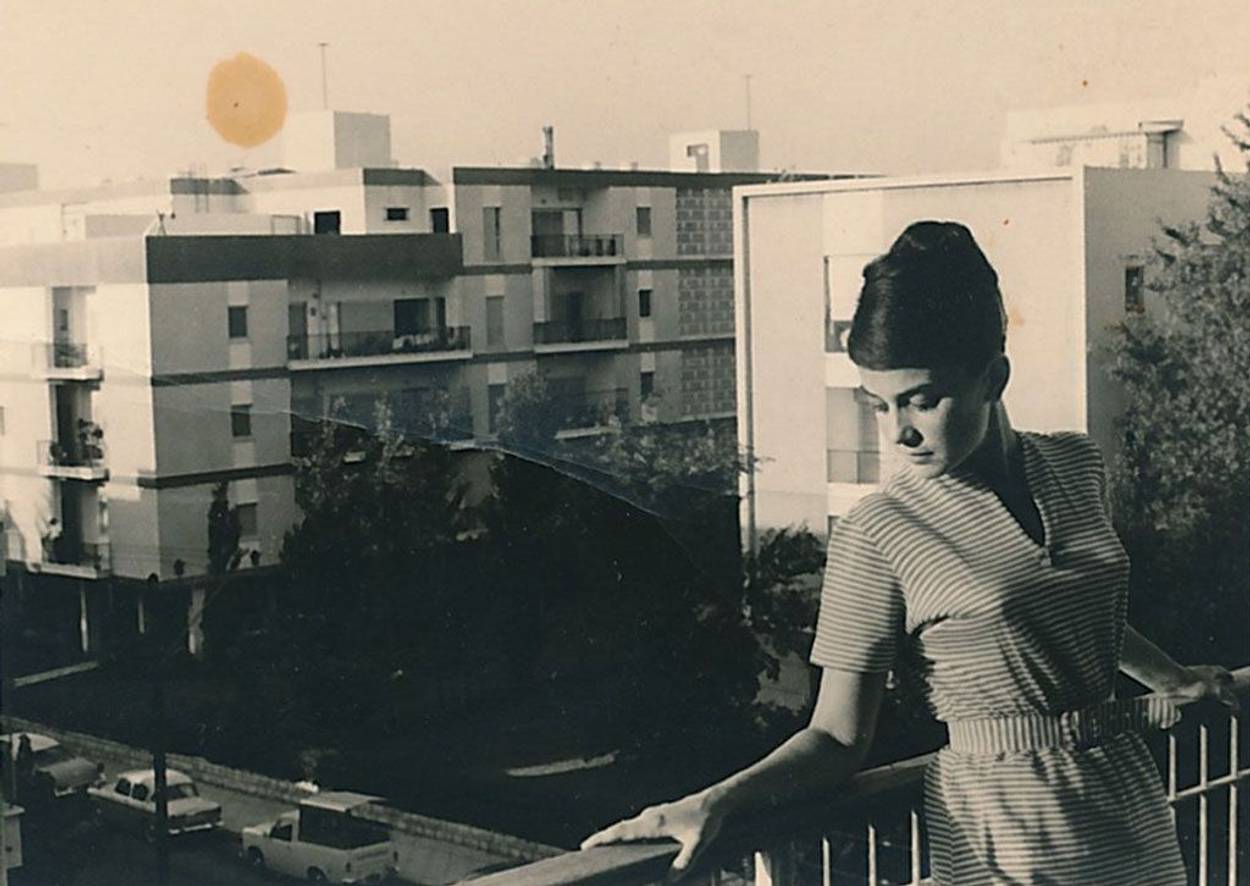

The newlyweds moved to Tel Aviv and lived there for four years. Janet remembered this as a wonderful, emotionally fulfilling period in their lives. Gideon’s extended family in Tel Aviv had embraced her. She learned to speak Hebrew fluently and was thrilled to be having healthy babies—first Perry, then Sabrina—born 16 months apart. For a period of eight months, Gideon was transferred to Paris; then the family returned to Tel Aviv. Perry was too young then to remember specifics, but he recalled that his father was “incredibly ambitious,” displaying the drive that would lead him to found the Gartner Group (now Gartner, Inc.), the first of several successful companies that would establish him as one of the pioneers in the new industry of information technology. Returning to the United States, they eventually settled in Mamaroneck, New York, where their third child, Aleba, was born.

And Janet and Gideon wrote each other love letters. Throughout their marriage, they communicated through music, and regularly exchanged letters—sometimes mailed, often left on each other’s pillows—that paint a complex, profound, private portrait of a marriage. But if one wonders what set Gideon apart from Janet’s other suitors, this simple line may explain it: “To you,” she wrote to Gideon in a letter of 1961, “I’m real.”

Now a married woman with three children, Janet started receiving notes and letters again. She knew who was sending them. Erich had become a professor of Greek and Latin literature at Yale and had also met with success as a Hollywood screenwriter. She figured Erich for a prolific writer who’d simply gotten in the habit of writing down and mailing his thoughts to her. Every once in a while, she responded with a brief note and didn’t ponder the matter any further. Meanwhile, in 1968, her sister Deborah co-founded the pioneering environmental design/graphic arts firm Sussman/Prejza, which became one of the most influential design companies in the country.

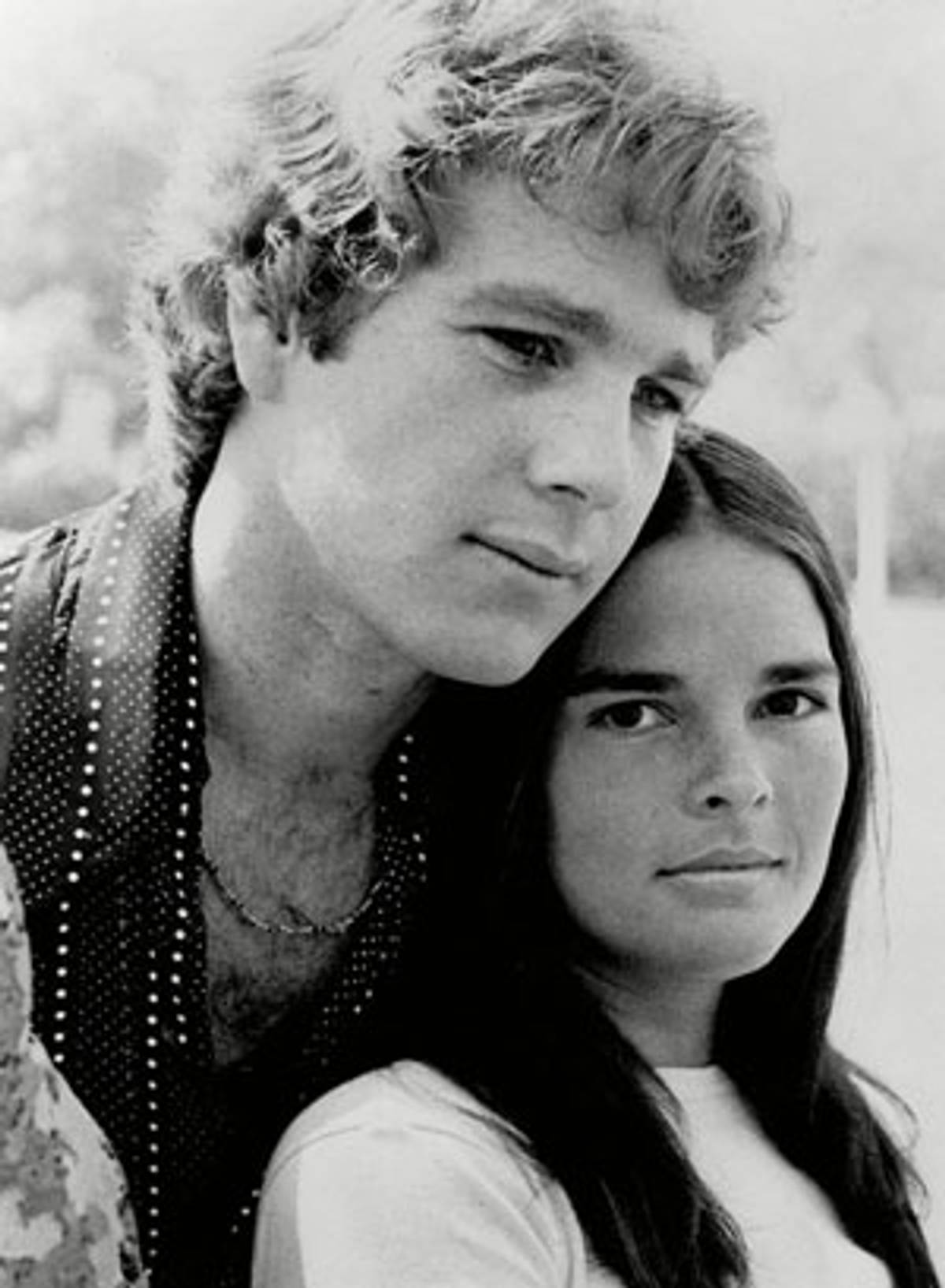

In 1969, Janet’s entire young family was sound asleep when the phone rang at 3 a.m. It was Erich Segal. “He was soused,” Janet recalled. “He told me that he’d just written his final love letter to me and that it was over a hundred pages long.” That last, very long letter was Love Story. A shortish novel, it became the best-selling book of 1970 and made Erich an instant millionaire. When the film exploded the following year, Erich invited Janet to accompany him to the Plaza Hotel in New York City, where she dined with him and the film’s stars, Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw, as well as the producer, Robert Evans. Janet recalled: “Gideon said I could go—however, he stipulated that I couldn’t be identified to the press as ‘Jenny’.” She attended the fête as the “mystery woman.”

In the silence, the mystery surrounding Janet’s identity merely thickened, until that fateful conversation in 1998 which transformed Tipper from Tennessee into Jenny from Rhode Island. As result of that story, Erich stated publicly that Oliver Barrett IV had been partly inspired by fellow Harvard student Al Gore, the son of a senator and a WASP product of prep schooling, but he’d given Oliver the personality of Gore’s roommate, Tommy Lee Jones, the poet-cowboy actor from Texas. But what about Jenny?

Though Erich never came out and declared in so many words, “Janet Sussman is Jenny Cavilleri,” he admitted as much in an extensive interview for the May 1971 edition of the Italian magazine Oggi. In addition to describing his changed romantic prospects in the wake of sudden wealth and fame, he confessed his feelings for “Jenny” at length. “When you lose the woman you love,” he said, “it is over for you, whether she leaves you for another man, or she dies. You are still alone. It was at this point that I started thinking about Love Story. That’s why in the book, Jennifer dies, because for me she had died.”

The interview included a photograph of Erich and Janet on the Promenade des Anglais on that trip to France in 1960. The caption, in Italian, identifies Janet as “Jennifer, the muse,” and states plainly that the woman in the photo, Janet, is the inspiration for Love Story. Like “Jenny” as described in Love Story, Janet was: “beautiful. And brilliant … loved Mozart, and Bach. And the Beatles.” Was affectionately called “Four-Eyes,” hated her glasses and removed them at every opportunity. Was a music major, though Janet went to Barnard and also majored in French, whereas “Jenny” attended Radcliffe. Jenny/Janet was an accomplished pianist, an intellectual in the habit of biting her nails, quick with sarcastic retorts, especially with men, and she often used the word “stupid” to express her impatience.

It’s fun to re-read Love Story in light of the history shared by Janet and Erich, as it turns his prose into something far more confessional and intimate. “Either way I don’t come first,” Oliver complains on the very first page, “which for some stupid reason bothers the hell out of me.” “I would like to say a word about our physical relationship,” Oliver begins chapter 5. “For a strangely long while there wasn’t any.” But Jenny is working-class Italian American, and Oliver is a wealthy WASP. Or, as Jenny says, “Ollie, you’re a preppie millionaire, and I’m a social zero.” There is nothing of Jewishness in the novel, which instead celebrates Anglo-American culture and values to the point of pandering. Jewish identity comes up only twice in the book, first when Oliver remarks that the editor of the Harvard Law Review, Joel Fleishman, wasn’t very articulate; and second, when Oliver graduates from law school and is job hunting in New York City. He declares:

I enjoyed one inestimable advantage in competing for the best legal spots. I was the only guy in the top ten who wasn’t Jewish. (And anyone who says it doesn’t matter is full of it). Christ, there are dozens of firms who will kiss the ass of a WASP who can merely pass the bar.

Given that Erich’s father and grandfather were rabbis, this is a curious statement that suggests he envied structural whiteness even as he prided himself on succeeding on his own intellectual merits. In his mind, nonetheless, WASP status seems to have been tied up with better success with women. In the Oggi interview, Erich described one of his final in-person conversations with the “real” Jenny, i.e., Janet, which took place at a restaurant following the book’s release. In it, he not only confirmed to her that she’d inspired the character, but believed that if he’d only been an Oliver in real life, “we would have gotten married”—an assumption that has no basis in Janet Sussman’s subsequent life.

Janet still seems amazed that she had such an impact on Segal and even more confounded that this story would have resonated so strongly with the public. “It was only many years later,” Aleba remarked, “that I realized how difficult it must have been for my mom to be the invisible muse, the real-life healthy living inspiration for this dead heroine in this impossibly huge best-seller and film. She never ever expressed this, but how could she not feel the frustration? They must have had a silent agreement not to make a big deal out of it, in part out of respect to my dad and us three kids.” (After 17 years of marriage, Janet and Gideon divorced, the way couples do once the children are out of the house. Though there have been suitors over the decades since that split, she has not gotten remarried.) Her middle child, Sabrina, clarified: “She had—has, really—no idea how surprising it was that she resisted Erich without thinking much of it. She has a way of doing that, living her life on her own terms, even as others seek to be part of it.”