Make Some Noise

Nadav Samin was a nice Jewish boy in Brooklyn who made it big at a key moment in hip-hop history and then walked away to take up Middle East studies. Now it turns out he never really left rap behind.

Last month, Nadav Samin, a 34-year-old doctoral candidate in Princeton’s Near Eastern Studies program, wrote a smart takedown of Sarah Palin, Newt Gingrich, Rush Limbaugh, and everything else the far right has to offer. It was a rap, with couplets like: “The Jews are good now, said Father Coughlin from his coffin/ so Party people, back up off ’em.” It was the first true verse—fully realized bars, start-to-finish—that Samin had written since 2001. For those who identify as 1990s rap snobs, that decade-long lapse is a minor tragedy.

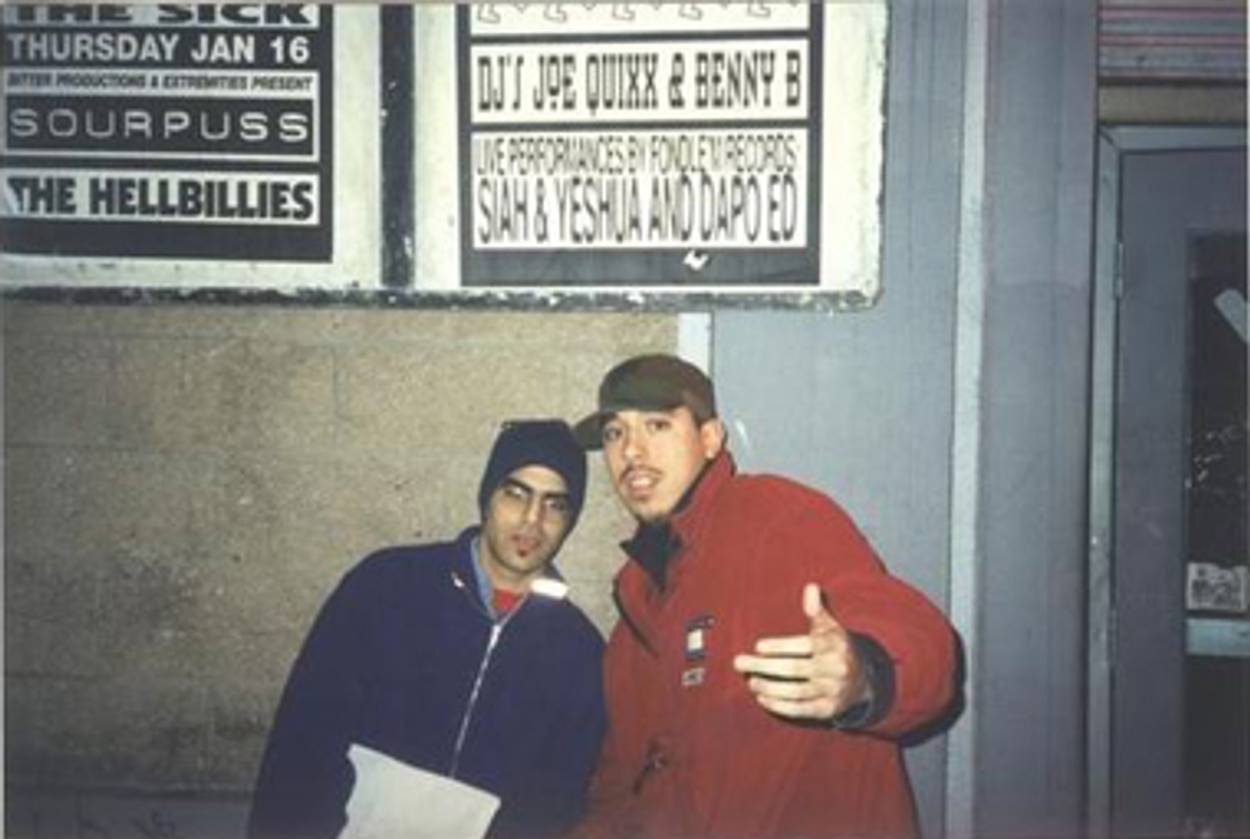

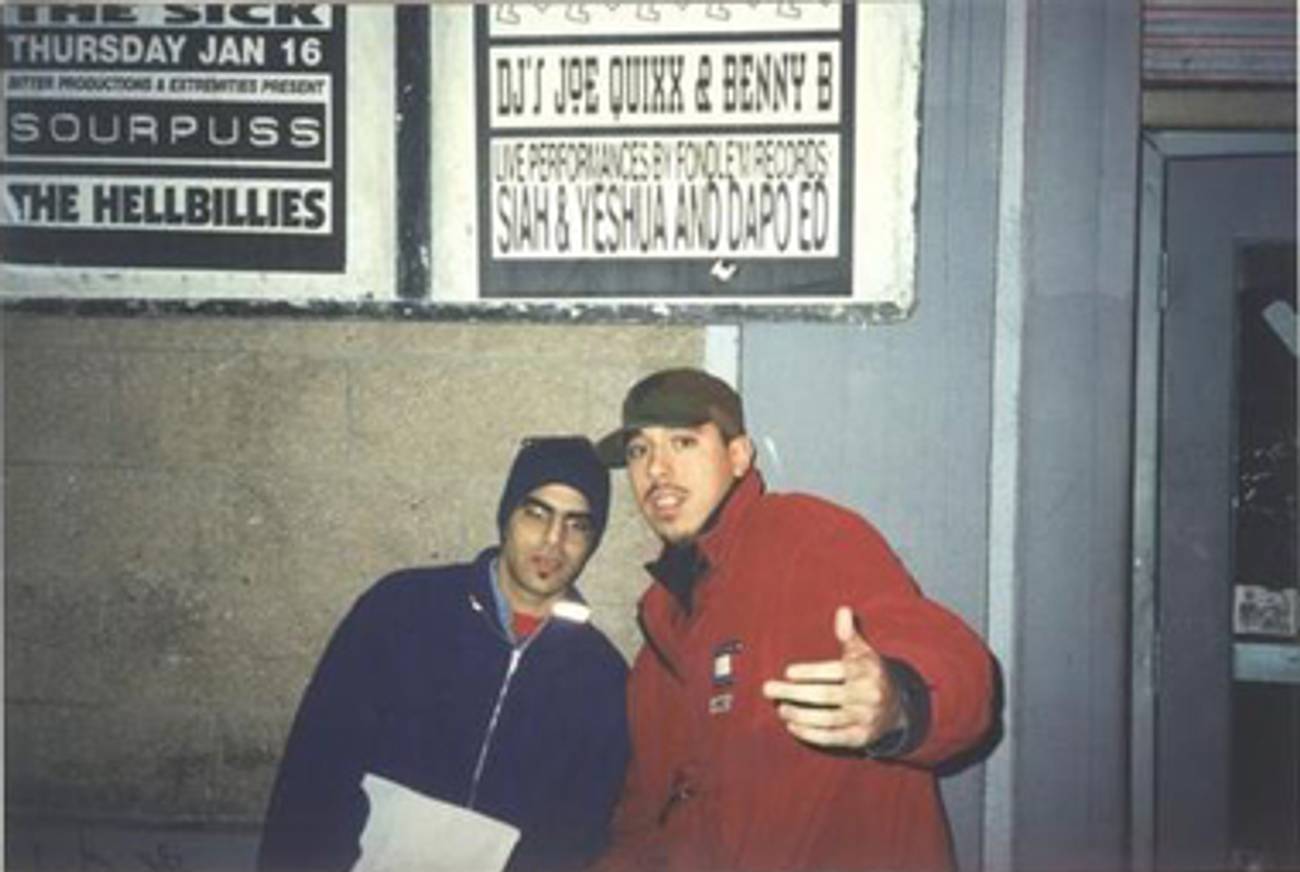

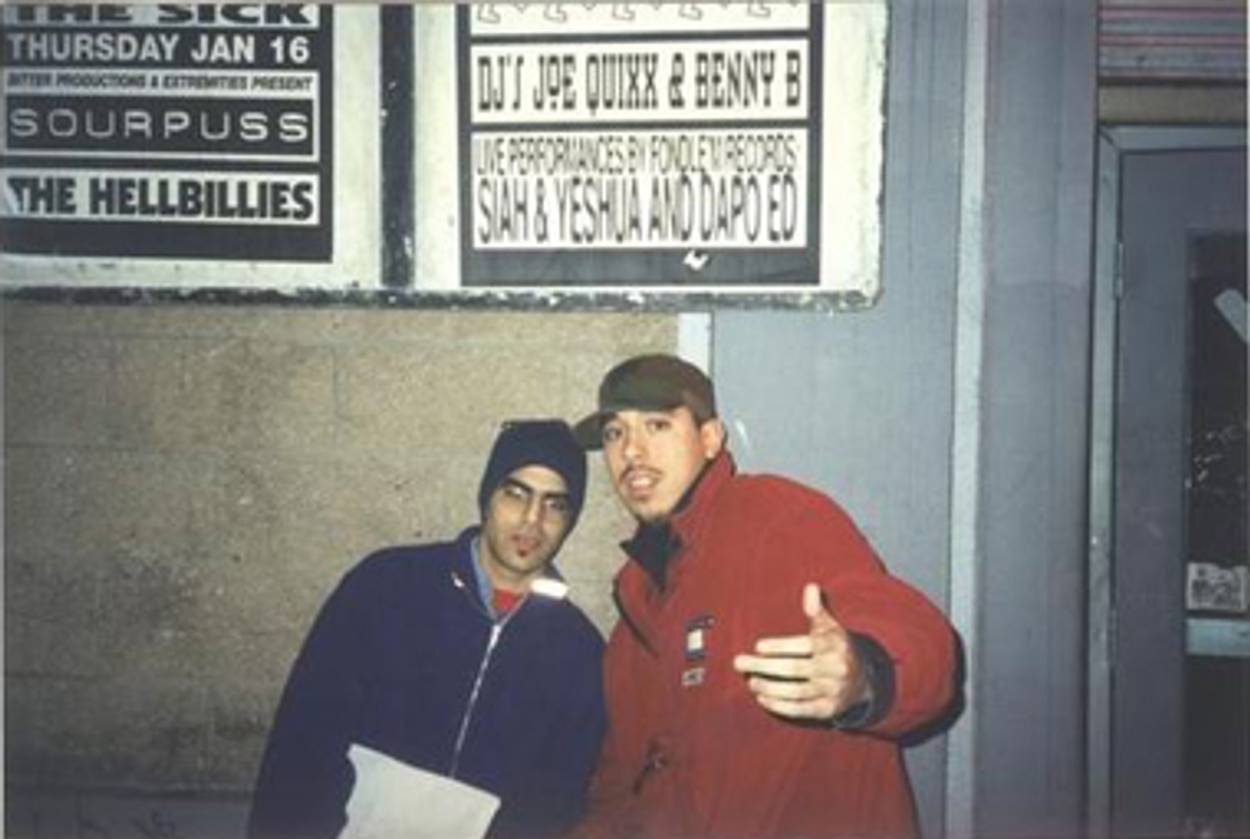

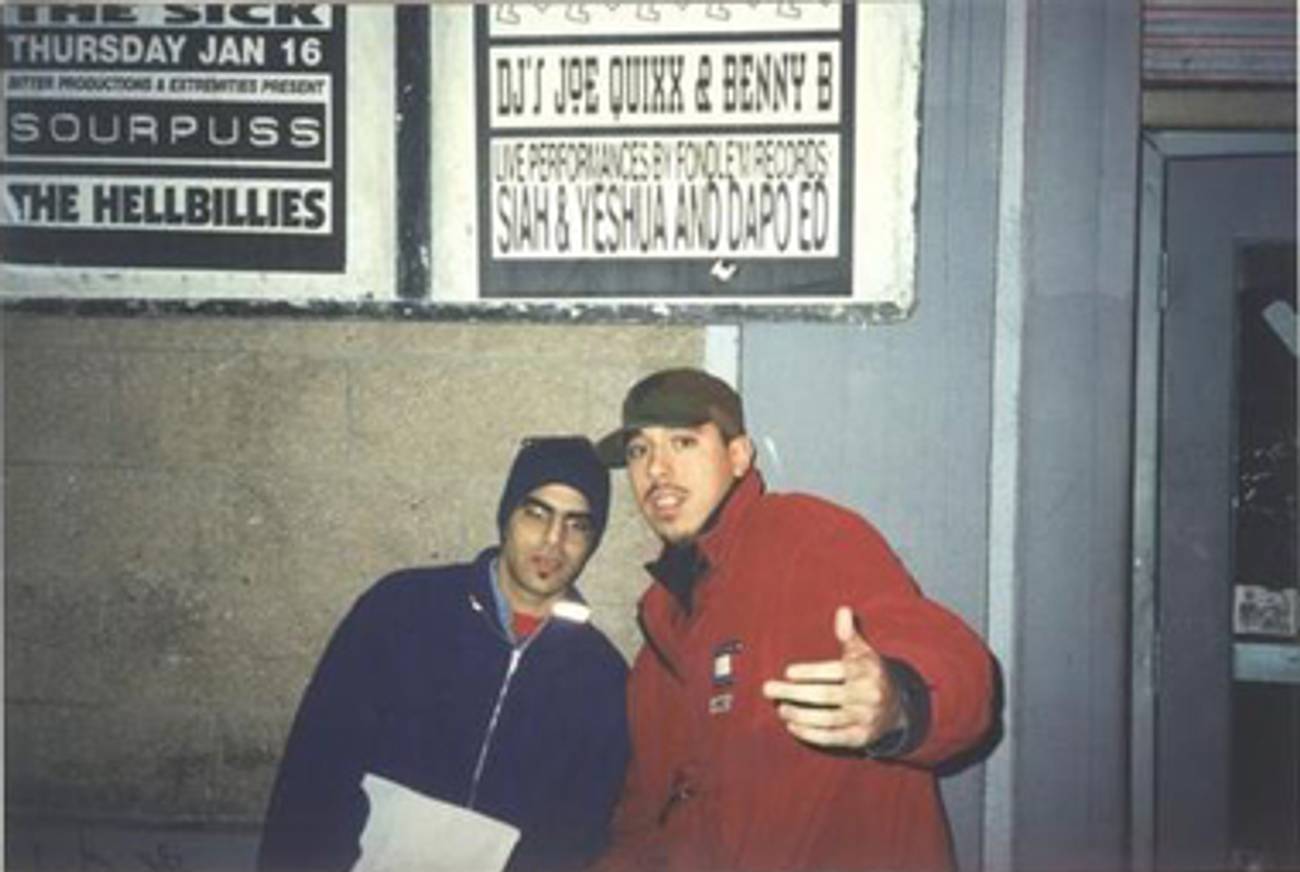

Samin was once better known as Siah, a Brooklyn emcee who worked in a duo with another emcee who called himself Yeshua dapoED. Siah was a nice Jewish boy from Manhattan Beach; his Colombian partner Yeshua—whose real name is Ed Avellaneda—lived down the way in Brighton Beach. Along with producer Jon Adler, the two released the hip-hop album The Visualz on a boutique label run by underground impresario Bobbito García.

Like everybody else in New York, they rhymed about how great they were and how much other emcees sucked. Siah and Yeshua’s capacious, vaguely metaphysical lyrics, delivered over jazz samples cribbed in part from Samin’s father’s record collection, made them at once innovative, warm, and very “real”—the buzz-word on both sides of hip-hop’s indie-versus-major culture wars. A small masterpiece, the EP culminated in “A Day Like Any Other,” an 11-minute fantasy adventure that, over multiple beats and abrupt shifts in mood and tempos, sent Siah and Yeshua off on a mysterious quest to save hip-hop from the clutches of fake rappers. It sounds hokey or contrived, but “A Day Like Any Other” won you over with its exuberance and sense of wonderment.

Their timing couldn’t have been better: Mainstream hip-hop was beginning its long, self-destructive infatuation with ditzy pop hooks and luxury goods, and the Internet was allowing New York acts to gain national visibility. What had been a local scene oriented mainly around open mic nights and García’s weekly radio show with DJ Stretch Armstrong was now reaching a network of true believers who got their fix via streaming audio, mail-order websites, and trades of third- and fourth-generation dubs. Yet The Visualz marked the high point of Siah and Yeshua’s careers, as well as of Samin’s engagement with hip-hop.

Today, Samin is an academic doing field work in the Middle East who quite credibly composes music for small ensembles and solo piano, for example, the recent “Wedding Song For Rolla and Charles.” Sometimes, he will rap along with Big Daddy Kane or A Tribe Called Quest in the car, much to his wife’s amusement.

Listen to “Wedding Song For Rolla and Charles”: [audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/audio/mp3/weddingsong.mp3]

***

Samin was born in 1976 to a Yemenite Jewish father and an Ashkenazi mother. He remembers getting props as an adult from Rahzel the Godfather of Noyze, an early beat-boxer—“white boy got skills!”—and yet he never thought of himself as facing the same obstacles, or providing the same sort of example, as older Jewish rappers like 3rd Bass or the Beastie Boys. In an interview last month, he brought up Passing, the work by the Harlem Renaissance novelist Nella Larsen, while turning her language on its head: “I have Yemenite looks, Yemenite features—I have always passed as a New York City non-Jewish, non-Caucasian, or at least can when I want to,” he said. “I like to say I could pass from Ecuador to Bangladesh, along that latitude line. It perhaps made it easier for me. I didn’t have to overcompensate.” Yet Samin had a strong Jewish foundation at home, attending Jewish schools and learning Hebrew at a young age. You can hear some of this in “Good Feelings,” a 1999 tune that was later featured on the JDub Records compilation Rooftop Roots. (JDub handles marketing and publicity for Tablet Magazine and its parent, Nextbook Inc.) With its Hebrew chorus and allusions to foreskins and shrouds, it’s a rapper’s assertion of self with unmistakable Jewish overtones.

Listen to “Good Feelings,” from Rooftop Roots: [audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/audio/mp3/GoodFeelings.mp3]

Samin found hip-hop around the age of 9 on the college radio station in his childhood home of Syracuse, New York. Soon, like many kids of his generation, he was the proud owner of Run-DMC’s Raising Hell and the Beastie Boys’ License to Ill—the two prime crossover texts of mid-’80s rap. Samin dabbled in composition, writing a parody of the Chicago Bears’ “The Super Bowl Shuffle” for a fifth-grade election campaign. When his family relocated to Brooklyn in 1987, Samin continued his informal musical education, turning to video shows like WNYC-TV’s Video Music Box to see LL Cool J’s latest, listening to DJ Red Alert on the radio, and undergoing his father’s aggressive course of jazz appreciation.

In high school, he tried his hand at hip-hop. “There were a couple of kids in the school writing rhymes, and I was like, ‘I could do that,’ ” he said. He had been hanging out with DJ Wave, who had a studio at his house nearby. Samin recorded three verses, over Black Moon’s 1992 underground hit “Who Got Da Props” instrumental, and then brought the cassette to school the next day to play for some friends, whose response was encouraging enough for him to keep at it. They said that Samin had a good voice for rapping, which is no mean thing: The late Guru, of Gangstarr, once recorded an ode-to-self titled “Mostly the Voice.” Hip-hop helped Samin find his way socially. “I’m a little guy and I have a big mouth,” he said. “For better or worse, people will always know that I’m around.” He added, “I noticed early that my rhymes gave me respect among some of the people who might otherwise be hostile.”

During this first year of rhyming, Samin also discovered the Stretch Armstrong & Bobbito Show, which aired on Columbia University’s WKCR radio Thursday mornings from 1 to 5 a.m. The show was a necessary stop for artists on the rise—its archives include early appearances by Notorious B.I.G., Jay-Z, the Wu-Tang Clan, and pretty much any other New York hip-hop artist of note from a certain era. Bobbito García also hosted open mics at several downtown clubs, including the legendary Village Gate. Stretch and Bobbito were key in establishing the purist, noncommercial underground as an end in itself. For Samin, that scene was a revelation.

Samin started college at New York University, but after a year, decided to move back to his parents’ house because he didn’t like living in Manhattan. Around this time, he was introduced to Avellaneda through a mutual friend. They started writing together. His friend Jon Adler, who was working in a jingle house, came to him with the offer of collaboration and free studio time. In 1995, The Visualz was recorded, and Bobbito agreed to release it on his fledgling Fondle ’Em label in 1996.

The EP earned rave reviews, and soon the duo was getting offers to perform outside New York. As modest as their success was, Samin still wasn’t sure how to deal with it: “I loved the accolades, but I also really detested them,” he told me. “In this little universe that I was inhabiting, I was a notable character, and I didn’t really know how to process it properly.” Bobbito offered him a valuable piece of advice—“don’t sell yourself short”—but Samin thinks he “took that advice too literally.”

***

Here’s where the story starts to get weird. Because Siah and Yeshua were part of what the hip-hop group Company Flow had termed rap’s “independent as fuck” moment of defiance, it’s easy to view their very limited discography as an enigmatic blip. In fact, though, for Samin, it was the business side that held him back. Following what he thought was Bobbito’s advice, Samin decided, as he put it, that “it has to be all about the business, it’s gotta be about the money. Not in a cynical way, but I took this attitude like, ‘If you guys like it so much, you’re gonna have to pay for it.’ ” In time, the focus on business soured him on making the actual music. His recording career stalled; he put out one solo single for Fondle ’Em, graduated from NYU, and spent three months hiking in India.

Then, on a Friday afternoon in early 1999, he got the proverbial phone call that changed everything. And it did, just not in the way it was supposed to. On the other end was Geoff Wilkinson, the founder of the early-’90s jazz-rap group Us3, who said he was putting together a record for Sony and offered to fly Samin to London to work on it at his home studio, after which would come future recordings and a world tour. “The deal memo had many more thousands of dollars than I had ever seen in my life,” Samin remembers. “I got a lawyer and we negotiated it, and then a few days later, I just said, ‘You know what? I don’t want to do this.’ It would have been the culmination of doing things with other people for other people’s music. I also didn’t want to enter the world of professional music with the musical ability that I had acquired up to that point: It was so inadequate, so rudimentary, and I was afraid that I would be stuck dealing with the image side of the business.”

“The lawyer,” Samin added, “was like, ‘I think you’re stupid, but OK.’ I think Geoff Wilkinson was like, ‘You’re stupid, but good luck.’ ”

Continue reading: “Pyrite,” Francis Fukuyama, and lyrics for Palin. Or view as a single page.

Samin began, in his words, to “drift musically,” which meant losing interest in hip-hop. He started practicing the piano three hours a day, taking lessons, and discovering just how much was packed into every measure of Debussy and Bartók. (He had already sampled the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt for “Repetition,” the A-side of his solo single.) The piano was comforting, resonant, and durable in ways that his walls of gear, and their unconscious drive to eat digital files alive, just weren’t.

Samin got increasingly serious about the piano, and after a brief post-college gig as a bike messenger, started a day job at a nonprofit journal for international affairs in 1999. The summer before, he had begun work on “Hairy Bird,” a suite of heavily electronic hip-hop whose structure was based on classical forms. He briefly reunited with Yeshua, who had since moved to the Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, an hour away from Manhattan Beach. Their subsequent break-up was almost anti-climactic; Samin swears there was no drama to it. (Of course, when you are talking about the dissolution of one of the great duos of mid-’90s underground rap, you want drama, but that’s not our story.)

For his part, Yeshua recently said on the hip-hop podcast Uncommon Radio that Samin had “a lot of people who were into him and a lot of fans, and I don’t know how comfortable he was with that. He was like, ‘I just want to be with my music.’ I know he’s still got the fire in him, but it’s just not his path.”

“Pyrite”, the B-side of that lone single, anticipates the problem, and Samin knew it at the time. “That song is where I run up against perhaps the main existential conundrum of any hip-hop artist: Once I’ve totally annihilated the competition rhetorically and destroyed any would-be pretenders, what do I do?” The chorus announced, caustically, that he had “Nothing to say about nothing to say,” and the verse was even more desultory: “Time won’t stop even if I ask nicely/ So nightly, I write the sweet nothing/ That’s seducing everybody and the hella fit/ Produce inadequate battle shit that’ll get me amped for like a week/ And then it’s just another freak.”

“I guess I answered the question by deciding not to say much at all anymore,” he said.

***

Samin’s undergraduate work had focused on the history and politics of the Middle East, and in 2000 Samin entered a master’s program at Johns Hopkins University. He found a mentor in Francis Fukuyama, the influential political scientist, and while the two didn’t always see eye-to-eye, Samin would end up co-authoring Fukuyama’s influential 2002 paper “Modernizing Islam,” which argues that while radical Islam posed a serious threat to the international community, its destabilizing influence could make it easier for the social and political structures of the Middle East to change. Samin began to learn Arabic, lived in Morocco, and returned to New York shortly before the attacks of Sept. 11.

That year’s “Hairy Bird: Reprise” marked the last time he really gave hip-hop a shot. There followed poetry, composition, dabbling in Egyptian music while living and traveling on a fellowship in Cairo in 2002 and 2003, but no more straight hip-hop. Once he finishes at Princeton, planned for 2013, there’s a good chance he will score a tenure-track job and teach kids who have no idea that mild-mannered Professor Samin was once one of the underground’s leading lights.

There was, however, one project in 2005 that seemed to bring together all of Samin’s interests. “The Long Night” is a decentered, tri-lingual account of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with professional jazz and Middle Eastern musicians as backing. The vibe may be remarkably similar to some of Samin’s work from almost a decade earlier, and yet, conceptually, “The Long Night” really exists in its own space. Asked by a friend to provide some music he could use in a soundtrack about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Samin decided to realize an idea he’d had at Hopkins. “I wanted to articulate a sense of the conflict as it was understood from the perspectives of the parties themselves,” he said. “I realized I couldn’t do that without the voices of those parties.” For Samin, that meant calling on friends around the world—while putting together the song in the studio. “I did this with some friends in Israel, with a Palestinian friend in Washington—she was calling her parents in the West Bank,” Samin said. “I was talking with my dad, he was helping me. I got other people involved in this process, and they were almost writing the lyrics for me.” This process also meant making sure he had the correct dialect of Arabic, and making sure that his Hebrew would pass muster with a modern Israeli.

Listen to “The Long Night”: [audio:https://www.tabletmag.com/wp-content/uploads/audio/mp3/TheLongNight.mp3]

“The Long Night” isn’t a mish-mash of other people’s sentences, but rather a cohesive, rhythmic whole. But that process, or various processes, of translation, might be why he doesn’t point to it as a return to hip-hop. Or maybe it’s because he didn’t write and record as himself: He was the orchestrator, the arranger, who just happened to see a role for himself. Also, as Samin added sharply, the English language viewpoint, including his own, is almost as relevant to the conflict as anything said in Hebrew or Arabic. “The Long Night” was released only on the Rooftop Roots compilation and Samin’s MySpace page. “And the music plays on even after we’re gone,/ from Brooklyn to Qadima to Ramallah and on.”

Samin was inspired to write “Lyrics for Palin and Gingrich” after Fox News condemned President Barack Obama for inviting rapper Common to the White House in May. The lyrics haven’t been recorded, but unlike “The Long Night,” they are unmistakably Samin going back to his roots, or coming full circle—to battle hymns in rhyme, the DNA of hip-hop lyrics and the first stuff any would-be rapper tries writing. “My love for hip-hop persists,” he said. “If this goes well, who knows? I might start doing these things more frequently.”

***

Lyrics for Palin and Gingrich

by Nadav Samin 2011

Sarah Barracuda here’s a rap clinic

your iceberg’s melting better grab on quick

to any or everything, still the middle won’t swing

cause you’re a feather that the weather floated into the ring.

It’s clear—the motion of poetry makes you queasy

we can slow the teleprompter take it nice and easy.

You and Newt would make a real good tandem

you’d wink at Muslims, he’d prod and brand ’em.

That so maniacally smiley aisle filler

whose voice echoes shades of sly killers

crossed with a gecko, that’s always out for tail

and when he speaks he blows wind—out of his sail.

He’ll promise diamonds, promise the Holy Grail

but all he cares for the cross is another nail.

I’m hollowing out around your Facebook race nook

it falls to pieces, like all your thesis.

The Jews are good now, said Father Coughlin from his coffin

so Party people, back up off ’em.

So Mr. Shutdown, as you’re known on the circuit

you’re the only man alive who’s famous for not working.

Bethlehem Shoals is a founding member of FreeDarko.com. He has contributed to GQ, Salon, and Slate. Follow him on Twitter @freedarko.

Bethlehem Shoals is a founding member of FreeDarko.com. He has contributed to GQ, Salon, and Slate. Follow him on Twitter @freedarko.