Makeover

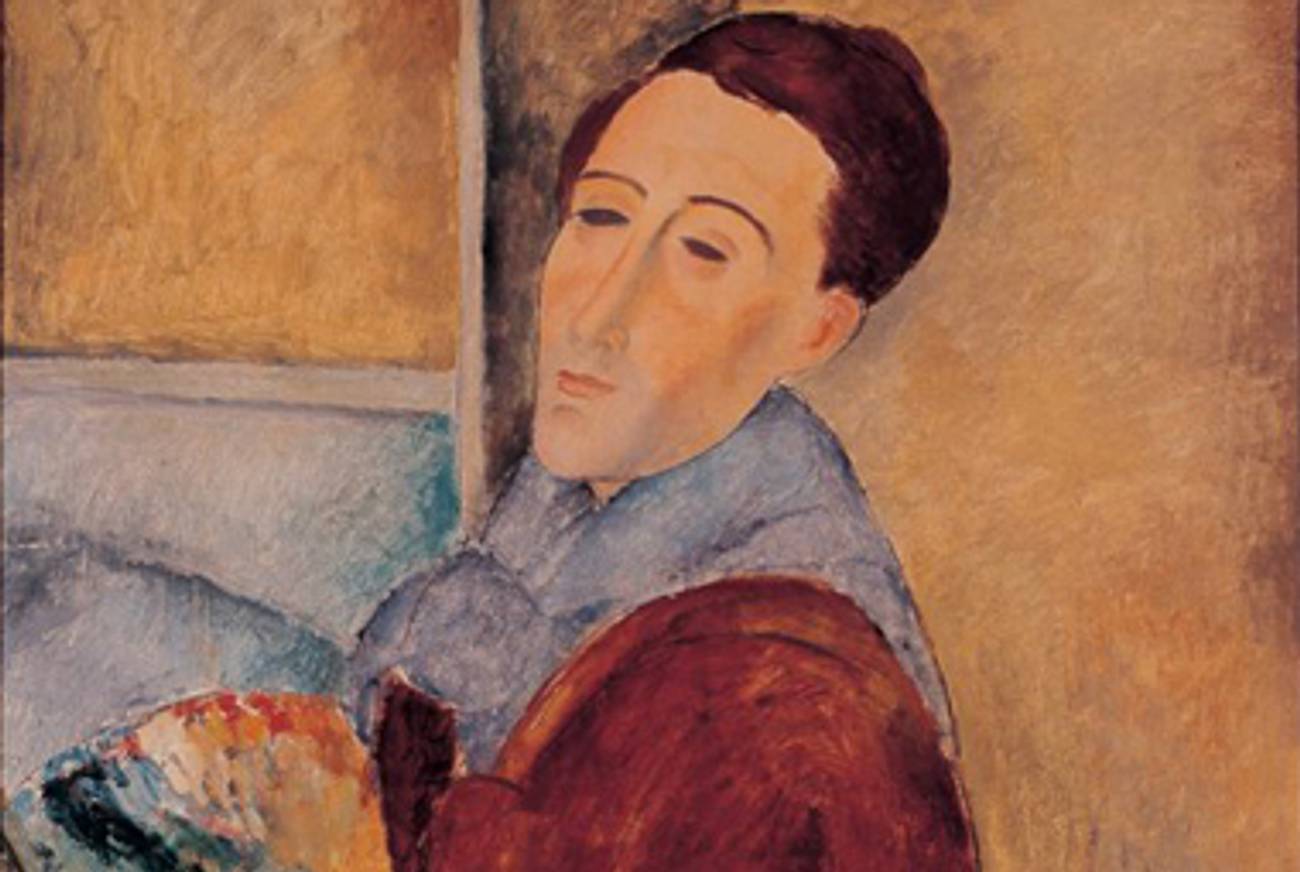

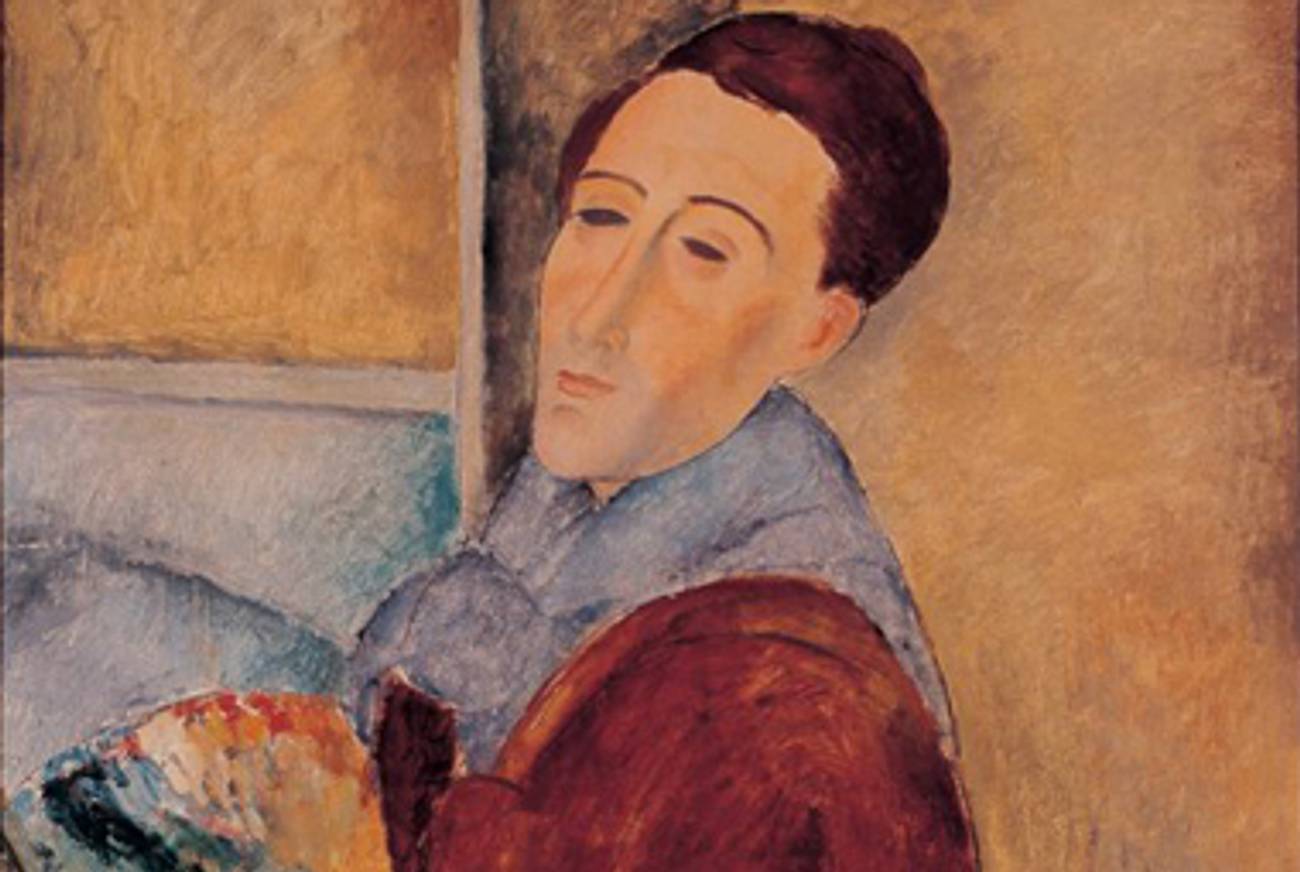

A new Modigliani biography tries to undo the painter’s reputation for drunken excess and bolster his standing as a serious artist

“Modigliani should have been the father of a family. He was kind, constant, correct, and considerate: a bourgeois Jew.” The English painter C.R.W. Nevinson, who rendered this verdict, knew full well that these were not the first adjectives that would spring to most people’s minds to describe Amedeo Modigliani. Jewish, certainly: He was born in 1884 in Livorno, an important Jewish mercantile center in Italy, to a Sephardic family that boasted of its (perhaps imaginary) connection to Baruch Spinoza. Bourgeois, at least at one point: The artist’s father managed the Modigliani family’s extensive landholdings and lead mines on Sardinia, while his mother’s family, the Garsins, ran a credit agency with bureaus in several Mediterranean cities. The union of Flaminio Modigliani and Eugenie Garsin was meant to unite these two prosperous clans, even though the bride and groom barely met beforehand.

Within 10 years of the marriage, however, both families had gone bankrupt; the couple’s house was foreclosed, and all their belongings were put up for auction. To make matters worse, Eugenie was then pregnant with her fourth child, Amedeo. And here, as so often happens when the painter takes center stage, the story becomes a little too good to be true. As Meryle Secrest explains in her new biography Modigliani: A Life(Knopf, $35), “the Modiglianis discovered an obscure Italian law that prevented the authorities from removing the bed on which a pregnant woman was about to give birth.” So they piled as many of their worldly goods as they could under the bed: “jewels, silver, clothes, laces, silks,” and so on. “The scene’s aspects are worthy of opera buffo,” Secrest comments: “the wailing family, the bailiffs methodically removing chairs, tables, beds, armoires.”

Did it really happen that way? After so many years, who can tell? In any case, writers on Modigliani have usually been happy to follow John Ford’s dictum: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” And the legends that cling to Modigliani all tend to undermine Nevinson’s praise of a constant and correct paterfamilias. If that was, in some sense, Modigliani’s destiny, he cast it off very early. Another often-repeated story has Modigliani discovering his calling as an artist at the age of 14, when he suffered a dangerous attack of typhoid. “Dedo said he wanted to study painting,” his mother recalled in a memoir composed decades later. “He had never before spoken of this and probably believed it was an impossible dream that could never be realized.” But she promised that if he recovered, she would get him drawing lessons. After studying with various teachers in Italy, he set out for Paris in 1906, where in less than 14 years he would produce the body of work that makes him one of the most popular—if not the most critically admired—artists of the 20th century.

Secrest tries to pry loose some of these encrusted myths. It is not true, for instance, that Modigliani suddenly decided to become an artist while at death’s door. One of his brothers recalled that, as a child, “Dedo” loved to draw on paper and, when the paper ran out, on the walls. But because Modigliani lived so fast and died so young—he was just 35 when tuberculosis finally took his life in 1920—he was the subject of many memoirs and anecdotes by other veterans of the Parisian art world, some of them by no means well disposed to him. And that world itself—Montmartre and Montparnasse in the years before the Great War, where modern art was born—has been as thoroughly romanticized as any in history. The unheated studios in peeling slums, the cheap meals at artists’ cafés, the parties at the Lapin Agile—Picasso, Brancusi, Apollinaire, Utrillo—all of them turn up in Modigliani, and it’s impossible not to thrill once again at the sheer bohemian glamour.

Secrest tells the story, for instance, of the dinner given in 1917 for the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and the artist Fernand Leger, both of them just discharged from the French army. Modigliani had recently broken up with his lover, the English journalist Beatrice Hastings, and she was planning to attend the party with his successor, a sculptor named Alfredo Piña. Knowing that the sight of them together would infuriate Modigliani, his friends bribed him three francs to stay away. But he could not resist: Just as Matisse was about to carve the turkey, the door burst open and Modigliani rushed in, heading straight for Piña, who in turn produced a gun and aimed it at Modigliani. Accounts vary as to whether Piña got off a shot, but in any case he was disarmed and Modigliani kicked out before anyone got seriously hurt. Marie Vassilieff, the hostess, made a sketch of the scene that is reproduced in Modigliani: A Life, and it’s hard to sense any real danger in it. As so often in this theatrical milieu, one suspects that getting talked about was the real goal of all concerned.

This is just the kind of story that Secrest would like to rebut. Modigliani, she argues, has become an icon of bohemian dissipation—the wildest, sexiest, drunkest artist in Paris—to the detriment of his reputation as a serious painter and sculptor. (“There was something like a curse on this very noble boy,” Jean Cocteau said; others said worse.) But Secrest insists that “coherent and guiding principles can be glimpsed in his life as well as in his art, despite appearances. In short, the apparent chaos of his private world threw an essential veil over the truth, buying time for him to go on developing as an artist.”

The problem is that, even in Secrest’s own telling, the chaos of Modigliani’s world is more than “apparent.” The fight with Piña really did happen, as did many, if not quite all, of the exploits attributed to Modigliani: not just glamorous ones like the legendary affair with Anna Akhmatova, but the years of alcoholic penury when he would exchange his drawings for drinks, and the many nights when he was discovered passed out on the street or in his studio. The best Secrest can do in the way of vindication does not change the overall picture. For instance, she argues that, contrary to legend, Modigliani could not actually have thrown Hastings through a window during a drunken fight: “It strains credulity to believe that Modigliani, at five foot three or four and now ill, could have summoned the strength to toss Bea through a window with the necessary force to break glass.” More likely, Secrest writes, “Hastings fell or was pushed backward and ended up against a window.” Maybe—but the impression the reader is left with remains basically the same.

Secrest’s strongest argument is that previous biographers have not given enough weight to Modigliani’s battle with tuberculosis. If he became an alcoholic and a drug addict, she writes, it was mainly because he was trying to find relief from his symptoms. (Because Modigliani wrote nothing about those symptoms, Secrest quotes accounts from other famous TB sufferers like Keats and Katherine Mansfield.) By the end of his life, when his behavior was at its most floridly bizarre—dropping his washbasin out of an open window, then perching in the window himself and “singing at the top of his voice”—Secrest plausibly suggests that he was suffering from dementia brought on by tubercular meningitis. Secrest tries too hard to make TB the key to understanding Modigliani, but it is useful to remember, in our age of antibiotics, how terrifying the disease used to be, and how the certainty of a painful, early death could have tipped an artist’s life into recklessness.

What is missing from Secrest’s Modigliani, on the other hand, is an intimate sense of the artistic and intellectual forces that made his behavior, and his achievement, possible. Secrest is a professional biographer who chooses her subjects from across the whole range of the arts—she has written lives of Frank Lloyd Wright, Stephen Sondheim, and Salvador Dalí, among others. But she does not display a deep knowledge of Modigliani’s time and place, relying heavily on just a few historical works for context, and making some telling errors. For instance, to conjure the atmosphere of Paris in 1906, when Modigliani arrived there, she quotes a letter of George Sand: “People are mad, they’re intoxicated, they’re happy to sleep in the gutters & congregate in the heavens.” Secrest uses this as if it were a description of the bohemian luftmenschen of Montmartre. But in fact, as the date of March 1848 makes very clear, it is a description of the mood of the capital during the democratic revolution that had just driven Louis-Philippe from the throne; it has no relevance to Modigliani’s Paris.

On Jewish subjects, too, Secrest is not knowledgeable enough. This becomes clear from the moment she describes Modigliani’s Sephardic background, using The Joys of Yiddish as her source: “Unlike Ashkenazic Jews … the Sephardim spoke Ladino, were educated and cultured, and rose to positions of eminence in Spain, Portugal, and North Africa as doctors, philosophers, poets, royal advisors, and financiers.” What, all of them? There were a few famous, elite Sephardim answering to this description a thousand years ago; but there were precious few Sephardi philosophers and royal advisers in Livorno in the 1880s. Later on, while Secrest quotes Modigliani’s matter-of-fact assertions of Jewish identity—“I forgot to tell you I’m Jewish,” he told Akhmatova soon after they met—she makes little of the fact that he associated with so many Jewish artists and dealers. (Chaim Soutine, in particular, called forth a remarkable generosity in the infinitely more urbane Modigliani.) While Secrest’s book is an entertaining, colorful read, anyone looking for a more substantial take on Modigliani’s life and work would be better off turning to Modigliani: Beyond the Myth, the catalog of the landmark show at the Jewish Museum in 2004.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.