All That Is Solid Melts Into Berman: The Unkempt Emperor of New York Intellectuals

The late political theorist, Marxist philosopher, and urbanist, who died this year, was my teacher and spiritual guide

Sign Up for special curated mailings of the best longform content from Tablet Magazine.

Many fine appraisals and recollections of the life and works of Marshall Berman, the great political theorist, urbanist, Marxist philosopher, and supreme lyricist of the enchantments of metropolitan life, have been penned following his recent passing at the age of 72—felled by a heart attack while eating breakfast with a friend at his beloved Metro Diner on 100th Street in Manhattan. These have included the many elaborate sketches of his early grappling with the Faustian figure of Robert Moses, who leveled Marshall’s Bronx neighborhood of Tremont to make room for the Cross Bronx Expressway. From deep within the bowels of academia came accounts of his place in the neo-formalist and structuralist debates of the 1980s. Marshall’s colleagues and friends at Dissent, which published some of his greatest essays and whose board he sat on for many years, fondly recalled his contributions to the life of the storied social democratic magazine. His great friend Michael Walzer remembered his idiosyncratic personality and his boundless kindness. In Tablet, Todd Gitlin, like Marshall an important participant/chronicler of the tumult of the 1960s, wrote the very first obituary to appear after Marshall’s passing: He spoke of a “Marxist Mensch,” a phrase that provoked the editor of Commentary, John Podhoretz, to assert on Twitter that no one would ever speak of a “Nazi Humanist Mensch.” Podhoretz apologized for the comment the following day, clarifying that he meant to highlight the difference with which Marxism and Nazism are treated in contemporary public discourse. In death as in life, Marshall had the honor of being involved in internecine ideological warfare between small, New York-based literary journals of ideas.

Having cataloged the encomiums of his public achievements, I want to add one to his private ones. Marshall was my teacher as well as the coordinator of my undergraduate studies at the City University of New York, where I finished my university studies with a double degree in Intellectual History and Russian Literature. Marshall took me under his protective wing, and I adored him.

***

Marshall’s second- and third-generation Jewish immigrant milieu in the South Bronx resembled my own upbringing in Brighton Beach, the major difference between that “world of our fathers” and my own being the absence of any discernibly radical or self-aware politics: Everyday life in the worker’s paradise had the near-universal effect of turning most people exceedingly right-wing. Not only did the Soviet Union strip people of their cultural patrimony and knowledge, but it also unwittingly stripped away any possibility of a belief in positivist progress. Having emigrated from the Soviet Union with my family at a young age, I had not been old enough to imbibe the crushing noxiousness of life under state Communism. Growing up in Brighton Beach, my left-wing politics were a fluke—though, statistically speaking, it had to have happened to someone.

After reneging on art school and moving around from college to college as a transitive and feckless misfit, I wound up, by a stroke of luck, in the inspired and relaxed environs of the CUNY B.A. program, which allows self-directed students to compile their own program of study. One could, for example, take a class at the downtown business college Baruch on Monday morning, travel to uptown Hunter in the evening for a chemistry class, and then up to John Jay for criminal law on Tuesdays and Thursdays. I wanted to be at CCNY’s uptown campus merely for the pleasure of taking the train up to the campus and fantasizing about the fratricidal conflicts that had taken place between Trotskyists and Communists in the first and second annexes of the CCNY cafeteria. What I craved more than anything else was to have been there in the 1930s and ’40s, in that romantic New York where conflicts over ideas mattered. Lost in my dreamy fantasies, I was intoxicated by the myth of the august intensity of the New York Intellectuals. I scoured used bookstores for old copies of Partisan Review and Dwight McDonald’s Politics, contemplated what Morris Raphael Cohen had taught William Phillips, and read Lionel Trilling, F.W. Dupee, Richard Hofstadter, Daniel Bell, Meyer Schapiro, Clement Greenberg, Saul Bellow, and C. Wright Mills. I rode the subway and read their memoirs, Norman Podhoretz’s Making It, William Phillips Partisan View, and Alfred Kazin’s Walker in the City. Their struggle to align the Thanatos of a roiling inner world and the demands of immigrant integration while speculating about the fashion in which one might live a politically engaged life mirrored my own.

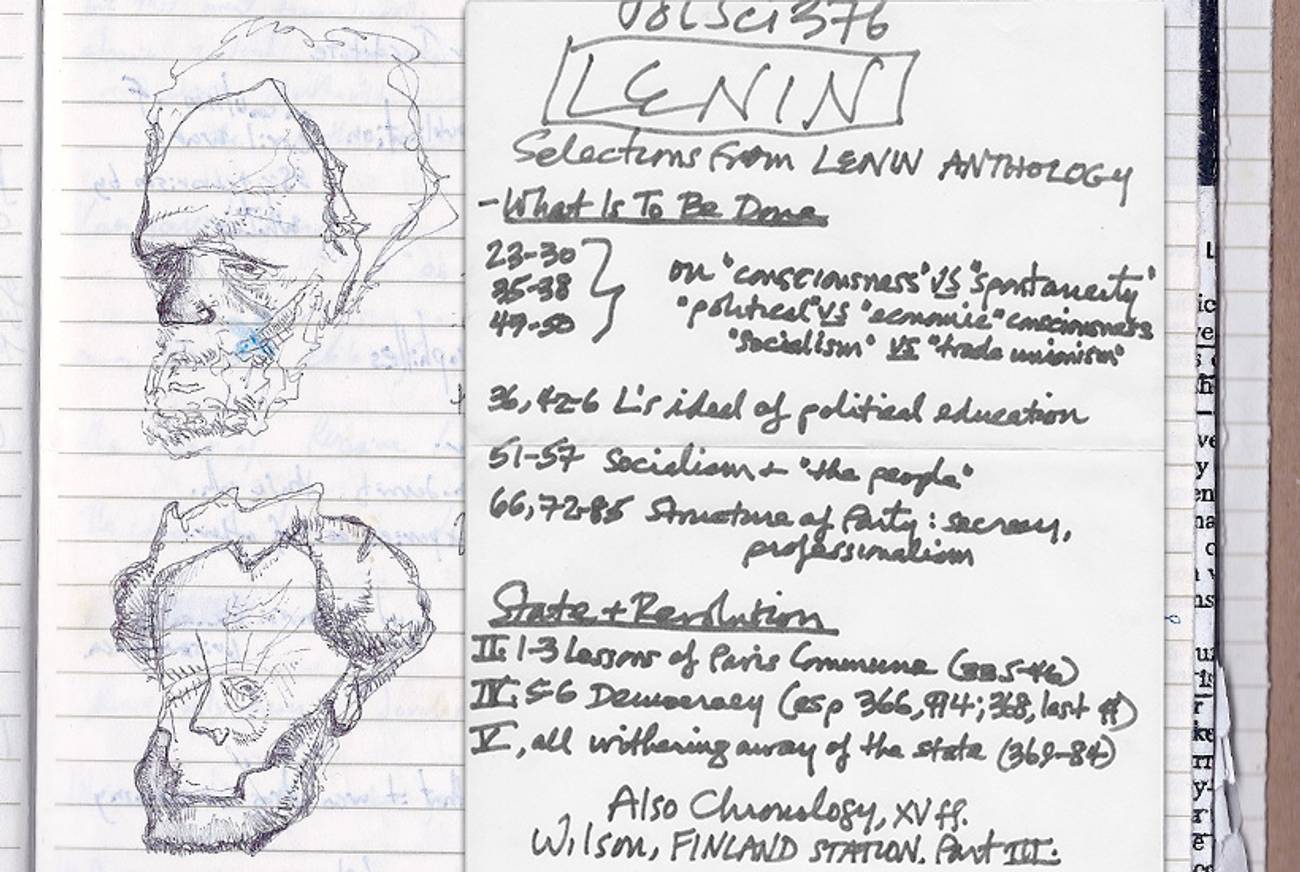

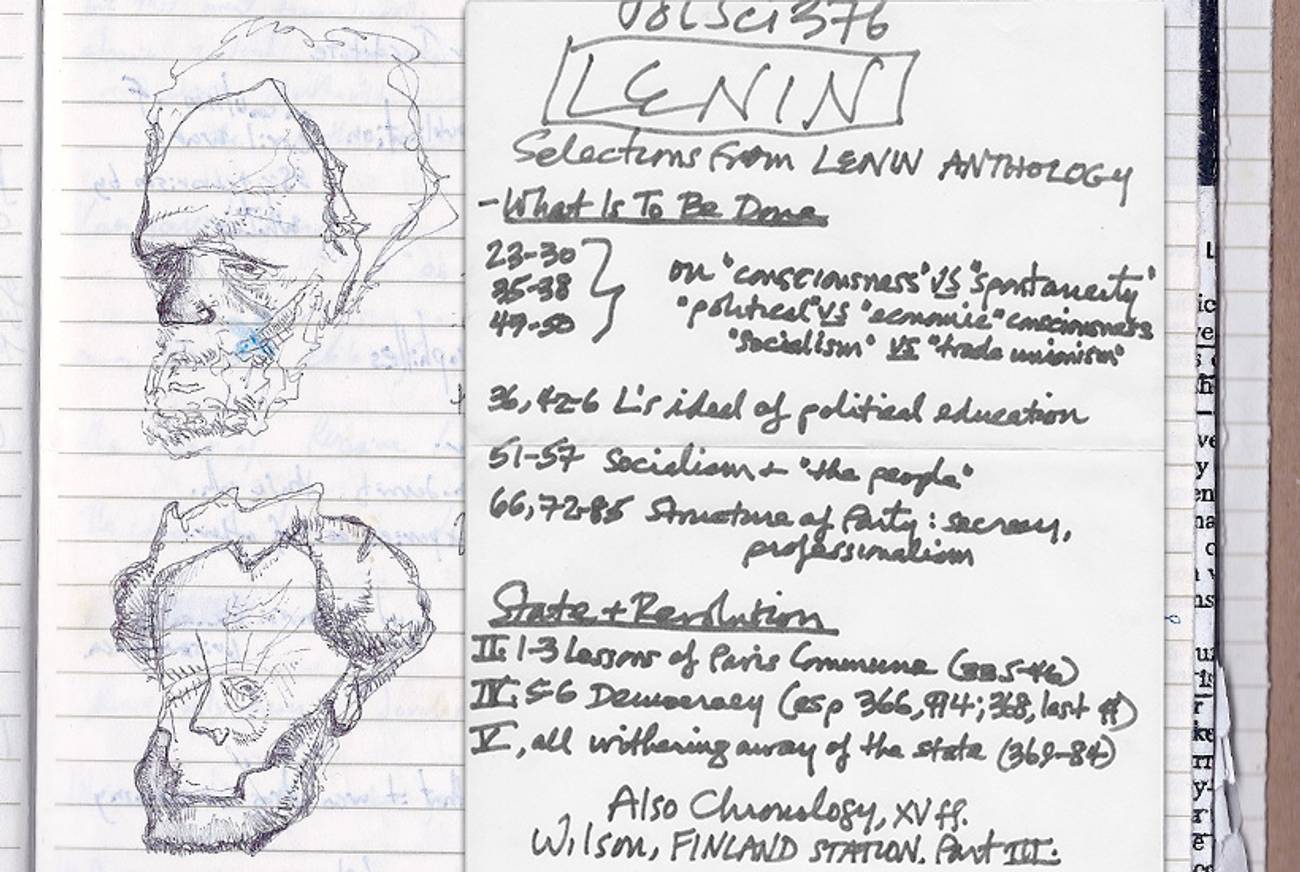

I was precocious enough to have read Marshall’s essays and book reviews in Dissent and the Times Book Review and to direct myself to his doorstep without quite knowing what it was that I needed or expected from him. The syllabus for “Marxism,” the class I stumbled into, was like nothing I had ever seen before: It was scribbled out in a thick, rickety scrawl of block letters across a purposefully crude photocopy. Dispensing with all academic conventions, it had nothing on it other than Prof. Berman’s name, contact information, and a reading list of five or six books.

The professor himself was even more strikingly contemptuous of any trace of conformism. With his thick, unruly mane of hair and unkempt beard, he was a stout and gentle giant, perennially shambling, with his bad back and ruined knees. He was the consummate anti-dandy, but with his orange jackets and tie-died T-shirts, he was still very much a peacock. I thought he was aesthetically marvelous, the very portrait of the scabrous, irascible, and cantankerous old Jewish intellectual I imagined I myself would one day become. The class was a remarkable and electrifying riff over 20th-century left-wing history ranging from Lassalle’s influence on Lenin to Bakunin’s reading of Burke, ending in Nietzsche’s idea of the nature of sensibility. Marshall would talk about various theories of repression and veer off on a tangent about Thorstein Veblen before delving into the fate of his Dickens-reading Iranian students who were being consumed by the ayatollah’s revolution.

In hindsight, I am impressed by how neatly he synthesized the brackish world of 19th-century Russian revolutionary politics for American undergraduates, light-years removed from it. I see, on opening my notes from that autumn, that the first line I wrote down in my notebook in that class might be taken for Marshall’s credo. “Must we wait for after the revolution for joy?” This was followed by a resounding “No!”

The centerpiece of Berman’s reading list was his magnum opus All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. Reading that book was a revelation, and I experienced a variant of his well-known reaction to his first (what came to be known as a “humanist”) reading of Marx’s 1844 manuscript: “Suddenly I was in a sweat, melting, shedding clothes and tears, flashing hot and cold.”

The immediate context for the book, the conditions under which it had been written and to which it responded viscerally was a vigil over the charred remains of the burned-out New Left and the cultural backlash that coalesced against the ’60s counter-culture. Before books like Zygmunt Bauman’s Liquid Modernity and Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism diagnosed the disintegration of the incorporated, coherent psychological self, Marshall pinpointed the unraveling of the identity structures of contemporary man. The book’s core insight was that the seams of received identity had become unglued, and inherited formulas no longer held, so it was the duty of modern man to construct and reconstruct himself and fill his own vessel.

Marshall’s magpie response was a call for a feverishly grasping appropriation of all that is best in literature, philosophy, and the social sciences. In a 1982 review of the book, John Leonard deduced quite lucidly that “according to Mr. Berman, all that is modern, in literature and the arts, in architecture and in politics, is sexy.” Whenever I met someone who was carrying a copy of All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, I knew immediately that this person was a kindred spirit, worth striking up a conversation with. Most often it would be an earnest Argentine or Turkish intellectual who would tell me ecstatically that Berman’s book changed their life. I knew what they meant. And how could one not love a man who slotted yiddishisms like mamzer and narishkeit into erudite essays like his rebuke of Irving’s rebuke of the New Left?

***

For a man of his stature and accomplishment, Marshall was an exceedingly generous mentor, though never a coddling one. He would forward me recommendations for fellowships to apply for and books to read, and he responded to every single one of the fledgling publications that I sent his way with equal parts praise and ribaldry, as well as humiliatingly incisive criticism. “Why have you made yourself into a Le Carré character, addressing us from some anonymous East European City?” he once asked me about a piece I had written about Rosa Luxembourg. After reading my appraisal of a Slovenian poet, he wrote back to rebuke me: “I don’t like the way you disparage Max Jacob. He isn’t my fave poet either, but people who die in Nazi concentration camps shouldn’t be dug up & dissed.” His correspondence was as inimitable as his conversation. Terse, cagey, and luxurious, it channeled his idiosyncratic character through shorthand and orthographic syntax. His letters and emails always ended with an exhorting “shalom.”

Here is one email he sent me last year urging me to get in contact with an up-and-coming Polish left-wing group of Revisionist Marxists whom he had visited in Poland:

Dear V—

There was an * I forgot to fill in. They translated my ADVENTURES IN MARXISM– & a bk of Mike W & one by Mike K–remarkably fast, w a delightful cover of M on a motorcycle. It contains an essay on Lukacs, 1st written in 1985, where I tell story of him & Irma Seidler, & I Say “What a great Hungarian movie this might have made!” But now [written in 90s] it’s too late…. All this was before I knew of H’s post-Waidja work as a director. But I mentioned the essay, & I said she was one of few authors I knew who cd put “love” & “communism” in same sentence & make it mean something–& I mentioned L in 1968, who said Russian Rev had exhausted its creative power, & “cinema is now the world’s avant-garde”. She was fascinated by this—others in aud yelled what were probably Polish curses at L….Who knows if anything will come of this?

Though it is written in a coded cipher, this letter makes perfect sense to me—as it probably does to others who spoke this hermetic language.

The last time we spoke was at the end of June, when I called him from Paris at his home on the Upper West Side. The day afterward, I was slated to catch the Eurostar to London and a train to Oxford for the 50th anniversary conference of the New York Review of Books, which was devoted to the memory of Isaiah Berlin, under whom Marshall had written his fateful dissertation on Marx during his graduate studies at Oxford. Berlin was the towering Russian Jewish émigré intellectual par excellence, and Marshall’s presence in Berlin’s circle in Oxford thrilled me, as it confirmed my own patrimony in the history of ideas I was obsessed with. Over the phone Marshall told me of his own disappointment that though “Berlin had been a great teacher and wonderful person in my life, for years people had been compiling a ‘kosher list’ of Berlin’s students that I and many others never made.”

During that call I related to Marshall what seemed to me to be a bittersweet tale of rejection: I had recently been invited by a common friend over to the palatial hôtel particulier of Isaiah Berlin’s adopted grandson, an important man in the administration of Sotheby’s auction house in Paris. Inside the mansion’s exquisite library stood Berlin’s desk, and over it hung the original of the David Levine portrait of the philosopher that had graced his pieces in the New York Review of Books. The gentleman’s art collection, full of Monets, Bretons, and Picassos, as well as his library, were suitably grand. The evening had gone well enough, I had thought at the time. The guy even got the Pasternak manuscripts out to show me and had me translate Pasternak’s faded wartime inscriptions to Berlin from the Russian (“Only you understand everything Isaiah”). He even pulled out the condolence telegram the queen had sent the family before the funeral (“I so enjoyed my afternoon teas and talks with Isaiah. My deepest condolences. Yours truly, Elizabeth”).

Afterward, my friend informed me that Sir Isaiah Berlin’s honorable descendant requested that he no longer bring the “weirdo intellectual” around. I was shocked and aghast at the world’s perfidy. Could this man truly not care about my encyclopedic knowledge of his grandfather’s obscure positions in the Oxford language debates of the 1930s! I complained about the incident to Marshall, who was typically livid at my lack of self-awareness: “C’mon man! What’s wrong with you!?” he bellowed at me through the phone, brusque and loving as always. “Not everybody can go everywhere and do everything! You’re from Brighton Beach! You should know better!”

Anyway, he went on, he loved my last article about the movies in Cannes and hoped that I could get to write more stories like that. It was a great way to spend one’s youth. He was waiting with bated breath to see the new Coen Brothers movie, and wasn’t it great that Jerry Lewis was still causing trouble at his age? I invited him to my wedding in the fall, knowing of course that he had teaching obligations and would decline graciously, secretly hoping of course that he would be in Europe for some talk and so might drop in.

After 40 minutes the conversation began to wind down, and I began to blurt out my gratitude to him. I thanked him for always having been so kind to me and for having taken an interest in me for all those years. “I was always glad to do it,” he told me. I did not know then why I had said it.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Vladislav Davidzon, the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review, is a Russian-American writer, translator, and critic. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.