A Russian Typewriter Longs for Her Master

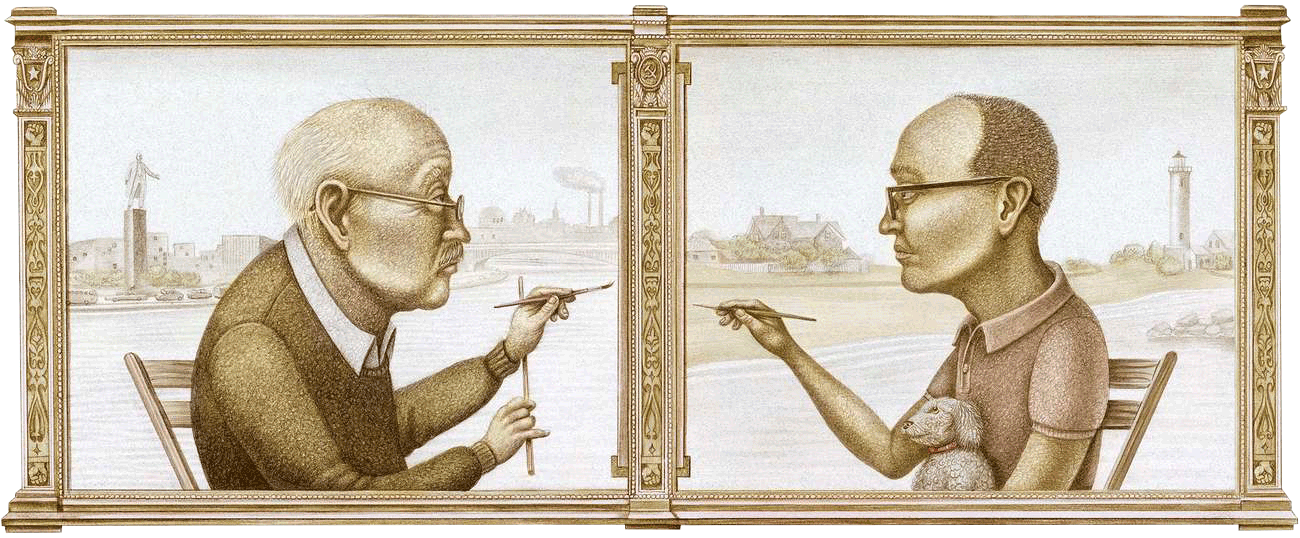

A portrait of my father, the refusenik writer and medical scientist David Shrayer-Petrov, as a New England poet, on his 84th birthday

Every year in May I drive to Cape Cod to get the house ready for the summer. It’s something of an annual ritual, which involves getting the long hoses out and turning on water for the outside shower, setting up the deck furniture, and, most importantly for me, planting the annual kitchen garden. In defiance of popular wisdom—and in keeping with childhood memories of the dacha we never owned back in Russia—I plant tomatoes before Memorial Day. Nine years ago, when we bought our place in South Chatham, I started an herb garden that now skirts the southern and western sides of the main house. Different types of mint, sage, oregano, and also horseradish have done well in the vicinities of a salt pond and Nantucket Sound. During my May visit I do a fair bit of herb-pruning. The South Chatham dacha is a place of family happiness, where we spend unhurried days and hours together, but in early May I like to go to the Cape alone.

The 2019 May visit was different because I had another being with me at the dacha, a 3 1/2-month-old silver French poodle. This was young Stella’s first visit to South Chatham. Vernal smells intoxicated her, and the nearness of rabbits, coyotes, and foxes made her wild with excitement. My recollections of the first night Stella and I spent at the dacha were layered with her restlessness. Stella wanted to explore the whole house, not just the upstairs bedrooms where we sleep, but also the downstairs guest rooms where my parents and my mother-in-law stay when they visit with us in South Chatham. Stella wouldn’t settle down long after her bedtime.

Only at the Cape dacha do I have such gorgeous technicolor dreams about my early childhood—the childhood that had occurred before the refusenik years when I tasted of alienation. If I’m allowed to sleep, uninterrupted, through those Baltic dunes and beach parties with unending badminton games and rhubarb cake topped with whipped cream, I wake up my most serene self. But on that particular night in May 2019 Stella’s throaty bark roused me from the projection room of sleep. “What’s the matter, Stella?” I muttered as my left hand groped for spectacles on the nightstand. It was 3:30 in the morning.

Stella whined, her aristocratic muzzle pointing in the direction of the door. I picked her up and held her close to my chest. She stopped talking but continued to shiver and yawn. I understood that my dog was reacting to an odd vibrating sound coming from the downstairs. It sounded like the pipes banging in unison, and I thought of young Mayakovsky asking us to “play a nocturne/on a downspout flute.” The sounds had a distinct cascading quality, as though somebody played scales up and down an old piano with broken strings. Yet it wasn’t raining. Stella in my arms, I descended the narrow stairs and stopped in the kitchen, listening closer.

We followed the sounds down the hallway to their source, which I now knew was in the smaller bedroom, where my father sleeps during my parents’ visits. It was a room with two twin beds, a bedside table, a dresser with a mirror, and a bookcase overfilled with Russian periodicals, in some of which my father and I occupied neighboring pages, as well as Russian translations of various epic works, the complete 30-volume, Air Force blue Chekhov, and multivolume sets of the lesser Russian—Soviet—masters of the past century. Displayed on top of the bookcase were family photos and a black case containing my father’s old Russian typewriter.

Like some other material vestiges of our family’s Soviet past, the typewriter had been living at our dacha. I flicked the light switch and ascertained that the clamor emerged from inside the typewriter case, which throbbed and shook dangerously close to the corner of the bookcase, about to fall off. As Stella barked at the strange black object, I remembered how my father once told me that Chekhov’s stories exhibited fiction’s main secret, that “inimitable vibration of feeling.” I laid my right hand flat on the typewriter case and felt the lovely devils of a future story quivering and pulling at their notes of desire. Then I sat on the edge of my father’s bed, which I had remodeled and lowered. I put Stella on my lap, rubbed the silver furrows on her charcoal forehead, and said to my dog: “It’s OK, Stella. She longs for her old master. She’s calling for him.”

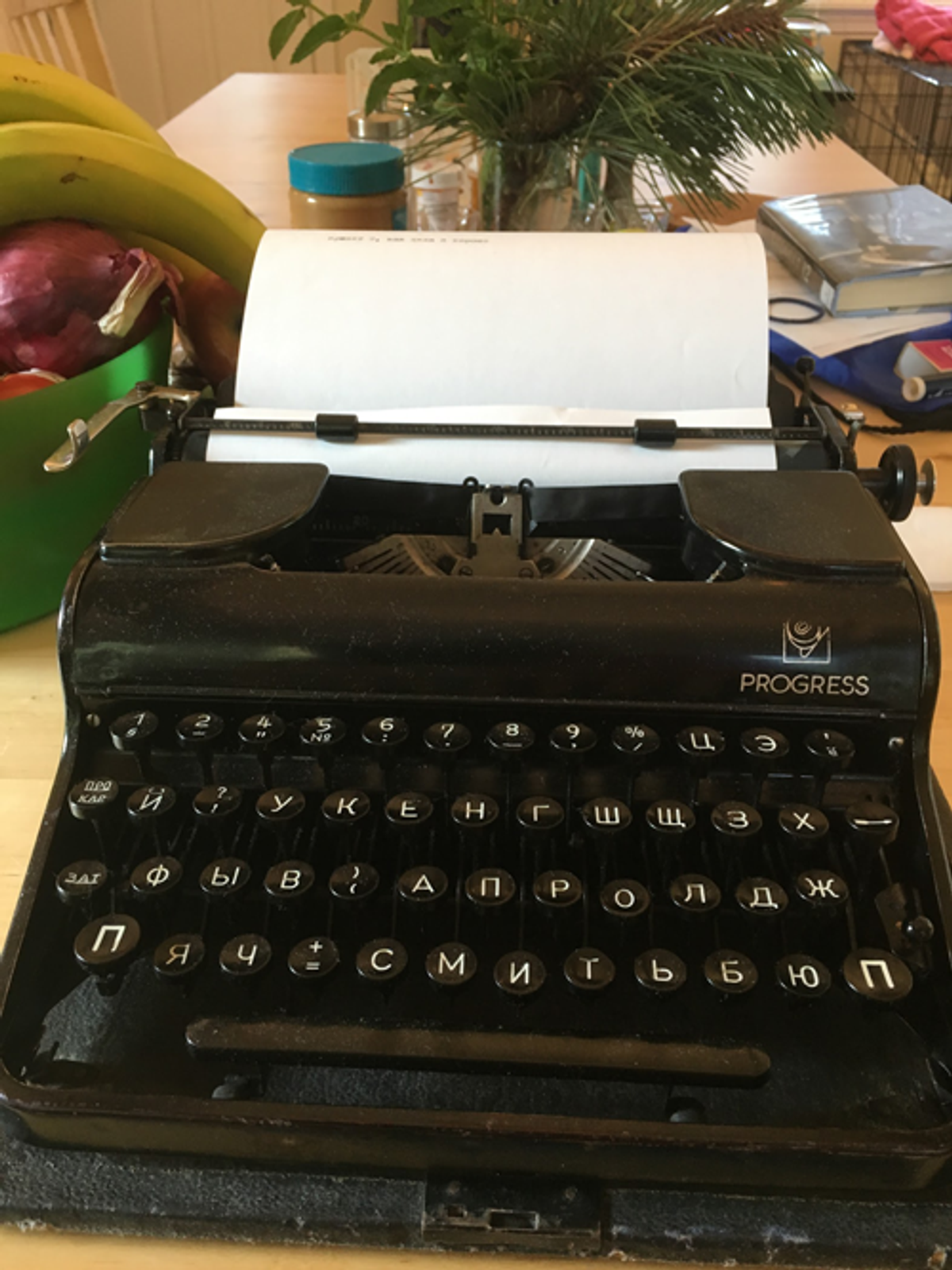

On the heels of the typewriter’s provocative behavior, I emailed my father, David Shrayer-Petrov, a writer and medical scientist: “Papa, your trusty friend misses you. Is it time to unretire her?” He understood what I meant, both about the typewriter and about coming to stay with us at the South Chatham dacha. The typewriter, its black case battered, its mechanism intact, is a German-made Olimpia Progress with Cyrillic keys. It was most likely manufactured in the late 1930s and came to the Soviet Union as a trophy of 1945. They don’t make such typing machines anymore. It was built to outlive political regimes.

Along with Erika, another German-made typewriter with a female name, Olimpia enjoyed legendary status in the post-Stalin USSR. “Erika takes four sheets,” sang Jewish Russian bard and playwright Aleksandr Galich in 1966, and his rueful aphorism both described the method of unsanctioned dissemination of writing in the USSR and spelled hope that not all was lost for as long as typewriters could be put to good use. My father was never a dissident by natural inclination, and only the refusenik condition pushed him to dissident activity. For much of his literary life in Russia he had favored individual open action—an attempt to steer a poem past the sluices of censorship or a public reading of a controversial text.

In spite of my father’s skepticism of the literary underground, back in the Soviet 1960s and ’70s his poems circulated in unsanctioned ways. I witnessed this as a child, especially during long train rides with my parents. Back then, my father knew many of his poems by heart and read them often, sometimes to smaller groups of chance companions. A fellow train traveler would hear one of my father’s unpublished poems and exclaim: “But I know it. You are the author?”

My two strongest childhood memories of my father are those of hearing him recite his poems and observing him at his typewriter. A whole film unfolds in my memory. I see him typing in the kitchen of our studio apartment near Moscow River Terminal; now he is composing at his desk—the door slightly ajar. At that time we had already moved to a co-op just steps from the Institute of Atomic Energy. My father would come home from his job as a research microbiologist, take a power nap for 15 minutes, have a shot of vodka with dinner, and then retreat to his den. Every summer, when we relocated to Estonia for a long stay on the Gulf of Pärnu, my father would leave the beach in midmorning, Olimpia calling. Increasingly drawn to prose fiction, he would spend long hours at his typewriter. My mother and I witnessed the creation of his refusenik novel Doctor Levitin, which was clandestinely taken out of the country and first published in Israel in 1986.

During my sophomore year at Moscow University, when poetry became my youthful métier, my father took me to Stoleshnikov Lane in the center of Moscow and bought me a portable Sarajevo-made UNIS tbm de Luxe. I felt immensely proud of this initiation. During the summer of 1986, our last Soviet summer, he and I both brought our typewriters to Estonia; sometimes we took turns, at other times we would perform a type de deux.

My father’s Olimpia isn’t only a writing tool but an important figure in his artistic universe, and I was fortunate to observe the birth of this literary character out of the ashes of refusenikdom. It happened just a few weeks prior to leaving Moscow for good. Through their refusenik activism, my parents had met and befriended Wyatt Andrews, subsequently a CBS national correspondent, who was at the time stationed in Moscow. In May 1987 Dan Rather came to the USSR with a crew of reporters, among them Diane Sawyer, to film Seven Days in May: The Soviet Union. They wanted to present a portrait of the country on the brink of change, and so they featured different facets of society, from then Moscow Mayor Boris Yeltsin, to anonymous drug addicts, to official Jews bent on staying, to Jewish refuseniks who had returned their tickets to Soviet paradise. Andrews suggested my father to the producers, they did a preliminary conversation with my parents to determine the scope of the taped segment, and in late May Dan Rather arrived at the doorsteps of our Moscow apartment. He carried a bubble of something impeccably American—tan dress pants, a navy blazer, athleticism—and looked like a visitor from a different universe. A combination of solemnity and absurdity hung in the air, and for some reason I asked Rather if he would look over my attempt at translating into English my father’s poem “King Solomon,” which could never be published at home. Rather read it, mouthing some words, returned the handwritten page to me, and said: “I like the way it rhymes.” Then my parents sat down for the interview, in which my father explained that refuseniks lived in a kind of “limbo.” Rather was whisked away, while his cameraman and soundman lingered behind.

“We want to film you at work,” the cameraman said to my father.

“You mean writing?” my father asked, smiling his signature half-smile.

“Well, perhaps you could just sit at your desk and type something,” said the American cameraman.

My father opened the case of his Olimpia, inserted a yellowish sheet of paper, and began to type. He improvised the opening of a new short story, titled “Dismemberers.” In the raw footage of the CBS documentary, you can see the first page of the story as it unrolls off the platen of my father’s Olimpia. In the final cut, you hear the ringing of bells, the staccato of keys, and you see a close-up of the top of the page with the emerging story. Years later, when the English translation was accepted for publication in Southwest Review, the then editor Willard Spiegelman told me that the story had a Gogolian quality. I agreed, with the caveat that it was Gogolian phantasmagory tinged with Jewish humor. In 2003 we anthologized “Dismemberers” in the collection Jonah and Sarah: Jewish Stories of Russia and America. When I teach the story, I picture my father, a tired 51-year-old refusenik writer, preparing to take leave of the land of his literary language:

It remained for me to place her beautiful body into the black leather case littered with early birdcherry blossoms, and to wipe off a few unwanted tears with the sleeve of my shirt. I had decided to give my Olimpia away. My thirty years of affection. My passion. The sole witness of my flights and falls. She to whom I entrusted my innermost thoughts, compressed into a line of poetry or extended into a short story. I used to take her with me wherever I went: deep into Belorussian countryside, to a cabana on the shores of the Black Sea, to Leningrad, to Siberia, to Tbilisi. … (tr. Maxim D. Shrayer and Victor Terras)

In the story, written ahead of emigration, the Jewish writer must leave his beloved typewriter behind the turnstile of Soviet passport control. He is exiled, but the typewriter refuses to accept the forced separation. She pines after her master and continues to type subversive fictions, using ripped-up curtains for sheets of paper. The fictional Olimpia is eventually destroyed, physically dismembered and annihilated by the writers’ friends—conformist Jews too terrified to safeguard the writer’s legacy.

In the story, the writer is never to see his loyal Olimpia again. In reality, on June 7, 1987, our family left Russia, carrying with us a total of four suitcases and two typewriters, my father’s and my own. While in Italy in transit and during the first year in New England, my father still wrote his new work on the typewriter. But as he likes to say, “life made its own arrangements,” and Olimpia was soon retired. My father learned word processing, and for over three decades he’s been writing on a series of Apple desktop computers.

***

The typewriter episode that occurred on the low verge of emigration is indicative of the many reasons why I admire my father. He doesn’t cease to make art from the foam and flotsam of ordinary life. Today, Jan. 28, 2020, he turns 84. “He’s still young,” is the comment I hear from American-born acquaintances who are unfamiliar with the circumstances of my father’s life and emigration. This is a very American comment about the prospects of aging. Most of my father’s American peers, the younger cohort of the “silent” generation, never experienced the horrors of the war and Shoah, nor did they taste of totalitarian rule. By Russian (and Soviet) standards, my father has outlived many of his academic and literary peers who were born in the 1930s and came of age during the war and the postwar paroxysms of Stalinist hatred. Add to that the years my father spent as a banished academic and writer, and you will have arrived at a more accurate calculation of his age. Existentially speaking, some of the Soviet years of his life count as two or three years each.

My father has lived a very full life, compared to which my own life looks boringly ordered and bourgeois. He got to do things I will never experience—from training on a Baltic Fleet submarine in 1958 to working in the midst of the 1970 cholera outbreak in Crimea. As a Leningrad teen he played chess with Boris Spassky; as a young poet he recited his poems before Anna Akhmatova and discussed with Dmitry Shostakovich the prospects of a Jewish-themed opera. Life brought him in contact with Nikita Khrushchev who was visiting a Soviet submarine with the then Czech leader Antonín Novotný; my father would later describe Khrushchev as a “jellyfish on the deck.” As a medical researcher at Moscow’s Gamaleya Institute of Microbiology, my father worked under academician Hovannes Baroyan, a medical researcher with the mantle of having been the Soviet resident intelligence chief who oversaw the 1943 Tehran Conference. In 1966, while researching a revisionist play about the revolution, my father interviewed Maria Fofanova, at whose apartment Lenin secretly stayed in the early autumn of 1917. (When he irreverently suggested that Fofanova’s bonds with Lenin were more than those of revolutionary comrades, the old lady demurred.) There are literally hundreds of stories like that, only some of them recorded in my father’s books. He’s always been more than a scion of Jewish Russian intelligentsia. He’s a son of the Vyborg working-class district of Leningrad and also a Russian boy from the village of Siva, which is tucked away in the foothills of the Ural Mountains, about 900 miles east of Leningrad.

My father’s deep knowledge of popular and peasant speech amazes me still today. He used to be able to place a person by region and province of Russia. In January 1998 I accompanied my father on his first trip back to Russia (I had already been back a few times). After a reading not far from Arbat Street, where in February 1987 my mother stood amid a small group of protesters facing plainclothes KGB thugs, father and I hitched a cab. Punctuating his mellifluous speech with undulations of his right hand, the driver delivered his opening tirade about the intolerable Moscow traffic.

“You must be from Smolensk,” my father said to the driver.

“Right you are, a smolyak,” the driver smiled broadly. “How did you know?”

“I have my ways.”

“You must be good with languages.”

My father just nodded, without saying “yes” or “no,” and the driver from the Smolensk province pried on.

“You look like a military man,” he said. “Oh, I think I know. You teach at the Military Interpreters School.”

My father beamed and fired off: “You’re right, I’m a Translator General.”

The driver loved it so much that he didn’t want to charge us.

For a lanky bespectacled man who, to a keen Russian phenotypicist, looks distinctly Levantine, my father exudes folk charisma, which I would define as ingenuity laced with mercurial wit. Sometimes the wit acquires dark shades, while at other times it sparkles with lightness. Two anecdotes come to mind. The first one is from the early spring of 1986, a few months after the worst period in our family’s refusenik years, when the Soviet secret police targeted my father and the threat of a prison sentence for anti-Soviet activity hung over his head. We were at a Moscow department store shopping for a birthday present for my mother. A line had formed before an electric-goods counter, where East German-made hair dryers were for sale. As we waited in the slow-moving line, a tired woman burdened with mesh bags, worried they would run out of hair dryers, looked at my father and said in the voice of a mob agitator:

“All those types come here and buy up everything. Nothing left for us.”

She didn’t single out Jews or people from the Caucasus, and yet the xenophobic implication was clear. My father retorted with an impromptu limerick, which I have tried to render in English:

“My dear lady, I traveled from Israel just to purchase a Russian hair blower, but I didn’t enjoy it and it turned out to be German, so I wish things were simpler or easier …”

The woman and others waiting with us in line lowered their gaze—either in shame or in disbelief.

That was a darker note, and now a lighter one. A few years ago, when my father was still inclined to travel long distance, we were in Israel together for a symposium and some readings. During the Q&A at the Jerusalem City Russian Library, which I was very happy to moderate, a Russian Israeli woman asked about Joseph Brodsky, with whom my father was friendly back in the days of their shared Leningrad youth. (Brodsky called him the last Jew writing mainly Russian love poetry.) My father told the story of how they first met.

“You’re better than Brodsky,” the woman commented.

“I know I’m better,” my father replied. “But who else knows that but you and me …”

Throughout his life, voices of Jewishness and Russianness sometimes produced harmony and sometimes refused to sing in chorus. A descendant of Lithuanian rabbis (on his mother’s side) and Podolian millers (on his father’s), he was born in 1936, the year of “Stalin’s Constitution.” His father’s family had ended up in Leningrad in the late 1920s. His father, an automotive engineer, and his mother, a chemist, both transitioned from a youth in the Pale to adulthood as members of the new Soviet intelligentsia. My father’s father volunteered for the nearly disastrous Finnish campaign because he saw it—rightly or wrongly—as a chance to fight fascism. Evacuated from the besieged Leningrad with his mother, my father spent three formative years in a remote Uralian village, in the region where Russians and Permyaks lived in neighboring communities. In the autobiographical novel Strange Danya Rayev, composed after emigration and included in the book Autumn in Yalta: A Novel and Three Stories, my father reflected:

Paskha, the Russian Orthodox Easter, was already approaching. Not the Jewish Passover, with matzo, with tales of escape from Egyptian slavery. … No one spoke to me about it. Probably mama and our relatives decided not to disturb my young imagination by reminding me about our Jewishness. Most likely, I forgot about being Jewish. It’s true, I did forget. So the delicious Easter cake kulich, the Easter eggs, which were dyed with paint made from onionskins, and which had to be rolled down a little hill made of wood, as well as the other culinary delights tempting an eternally insatiable boy, all impressed me as a real holiday. … Yes, I totally forgot who I was by birth. … I felt myself totally at home with the children of the Urals. (tr. Arna B. Bronstein and Aleksandra Fleszar)

Paradoxically, the return to Leningrad in the summer of 1944 reminded my father that he was different, Jewish. His siege-ravished city also brought him face to face with another traumatic realization. His father, a decorated frontline officer, first in the tanks, then in the navy, had a field wife, a Jewish woman, and a new family.

Growing up in postwar Leningrad, my father heard several tongues. Yiddish, the private domain of his grandparents’ home, reminded him of his roots. Soviet newspeak taught him to discern threads of truth amid publicly spoken untruths. A richly polyphonic Russian was both the language of street culture and high culture.

In July-August 2019 I interviewed my father about his first literary experiences. (We’ll soon return to these interviews.) He told me about an early spark of interest to both poetry and literary translation:

I was a fairly well known person among the local teenagers. I would make up all sort of mean pranks involving law enforcement officers; I snatched vegetables from trucks. In general, I led the life not of a boy from the intelligentsia but a true son of the working class outlaying districts. … And so I composed a poem, “Let me now tell you, fellas,/how I went skating to the rink,/Ninka the redhead was there skating,/and the whole gang in sync.” It was a long poem. I wrote it, I recited it, and it went around. Kids my age, my circle all knew it. That was my first close encounter with verse. Probably in seventh grade. … For some reason, I became interested in translation, why I cannot even imagine. … And I translated “The Fountain” [by the Boston poet and diplomat James Russell Lowell] from English into Russian: “Glad of all weathers,/Still seeming best,/Upward or downward,/Motion thy rest.” And the teacher liked it. … Actually strange things occurred.

My father came of age during some of the bleakest years for Soviet Jews, when Stalin’s paranoia about his subjects’ allegiances led to open vilification. The anti-Jewish campaign reached its peak in late 1952 and early 1953. Like most of his Jewish peers, during his senior year in high school my father saw his native country and the majority of her people prepared to impale their Jews. In the summer of 1953, just four months after Stalin’s death and the retraction of the charges against the Jewish “murderers in white coats,” my father entered the First Leningrad Medical School. Ahead lay a long double career. My father loved both doctoring and writing with an equal passion. (When we became refuseniks, and he was ejected from academic medicine and blacklisted as a writer, he supported us by seeing patients in a neighborhood health center.)

The years when my father studied medicine and entered the literary scene as a poet and translator were the early years of Khrushchev’s Thaw. Boris Slutsky, a Jew and a Communist, one of the Thaw’s soberest voices, who managed to get the greatest number of Jewish poems into Soviet print, suggested that my father adopt a Russianized literary penname, “David Petrov.” This didn’t ease my father’s passage into official Soviet publications, only betokening his dual identity. After medical school came the military service, to which my father volunteered as his father had over two decades before. “Why did you decide to serve in the military, that instead of doing public service at some rural clinic?” I recently queried my father. He replied: “I wanted to become a naval doctor. … I was drawn to the romance of naval adventures. … And so I chose the navy, and then, imagine, Khrushchev started the reduction of the military. … I had already taken the oath… Black hole… I found myself in Belarus, in a tank army.” After serving as a military physician, my father met my mother, Emilia Shrayer (née Polyak) at a family wedding (both families hailed from Kamenets-Podolsk). In 1964 they moved to my mother’s native Moscow, which became my father’s home for 25 years.

It took him longer than some of his Soviet peers to publish his first poetry collection, Canvasses, which came out in 1967 with a preface by Lev Ozerov (of the Babi Yar poetic fame). Two slim volumes of essays about poetry would come out in the 1970s, demarcating an uphill battle for admission to the Union of Soviet Writers. Viktor Shklovsky, the visionary of “art as device” whose own life bore witness to the destruction of the early Soviet avant-garde, was one of my father’s recommenders. I’m only registering some of the coordinates and landmarks of his life, replete with travel across European Russia, Siberia, and Georgia, with research on tuberculosis, staph infections, and phage therapy, and also with pushing the outer limits of what the regime would tolerate. Then came an open conflict over writing Jewish poems and a torturous decision to emigrate.

The application for an exit visa destroyed both of my parents’ careers, resulting in my father’s dismissal from the academy and public expulsion from the Union of Soviet Writers. Permission to emigrate was denied. Banishment from official culture resulted in the derailment of three books, one of which was already set in galleys. And then—almost a decade as refuseniks, persecution, Jewish struggle.

Now that my father was writing mostly in isolation and for his desk drawer, his creative work underwent a shift from mainly poetry and translations to short stories and long novels. (Of late, he has written less and less poetry as the short novel became his American form of choice.) Post-freedom came a new life in America, where we landed in August 1987, a “third life” (title of the third novel in my father’s refusenik trilogy) filled with its own immigrant hurdles, and academic and literary discoveries.

***

Life in New England offered a respite from refusenik days and nights. And yet this externally peaceful life hasn’t released my father from the baggage of memory, and his frail frame now carries its eight decades with more difficulty. This brings me back to the Cape Cod dacha, the mysterious vibrations, and the typewriter that refused to dwell in speechless exile. Over the years I’ve written essays about my father, and I’ve interviewed him about aspects of creative work and Jewish identity. I’ve co-translated and edited four of his books and helped organize his archive. I think I know and understand his life, and yet unanswered questions still remain.

After visiting the Cape in May 2019, and hearing the clarion call of his old typewriter, I realized that Olimpia was not only calling for my father. That summer my father and I planned to work together on the revisions in his novel Judin’s Redemption, which is next in line to be translated into English. Its draft completed back in Moscow in 1981, when my father feared for arrest and confiscation of his manuscripts, Judin’s Redemption is simultaneously a historical novel set in the first century CE in a Roman colony on the Black Sea coast and a Jewish fantasy of what my father calls “an attempt at exodus.” In 2005 an early version had been serialized in an émigré magazine, and we were now copiously editing the text in order to prepare it for book publication.

My summer plan for working alongside my father was threefold. My parents would stay with us for about a month at the Cape dacha. I would go through my father’s manuscript, make editorial queries, and use them as specific opportunities to engage him in conversation. I would keep a summer journal. We would take regular walks and chat without any specific focus. And I would record targeted conversations with my father. In those, I would concentrate on questions of writing, integrity, and emigration. Writing on—and out of—the ruins of another life. In late June and early July 2019 I traveled to Russia with my younger daughter, gave several talks and readings, conducted research on the writer Ivan Bunin, who is one of my literary heroes, and visited the ancestral graves in St. Petersburg.

My mother and father arrived to South Chatham during the second week of July. Over the next week, as we settled into a summertime family routine, nothing threatened the measured course of our dacha living. One thing was lacking, though. My father didn’t have his computer. He missed being able to write every morning and was at times given to restlessness.

On the fourth day after my parents’ arrival, I donned my old iPad, which I used to take with me when I did field research in Crimea, and my father and I sat down for a training session. In Russian an iPad is known as planshet, and this French-derived word originally referred to the military officer’s field briefcase or tablet. I thought the analogy would bring back memories of my father’s youth and service. “Well, Lieutenant Shrayer,” I said to him. “This is your new writing tool. It’s more like a flat typewriter than a computer.” I showed him how to start a new file and to switch to Cyrillic. He tried typing on the planshet, his tremorous fingers refusing to be nimble. He finished typing a sentence, and it was immediately transposed onto my iPhone screen: “I’m writing this at Man’ka’s and I’m typing idiotic words and signs.” I showed him the screen, “It’s all here, saved, you see.” My father was surprised, pleased.

During the summer, my wife comes to the Cape from Boston for long weekends. When she arrives, I spend a bit less time with my father. Sometimes we all go on family outings as a loud translingual group, only half of us American-born. On a Saturday in the middle of July, we drove to the center of town, where Ron Howard’s Pavarotti was showing at Orpheum Theater. I sat between my father and my wife. When Pavarotti sang, father was transfixed. His neck lengthened, his chest heaved; his lips whispered the lyrics (in Russian, not Italian) or hummed the melodies. I found particularly compelling the parallel footage of a young Pavarotti singing Cavaradossi’s aria at the end of Tosca (“E non ho amato mai tanto la vita!”) and an aging Pavarotti singing the same aria. And I’ve never loved life so much … After the movie, when we drove home through dusk, my father spoke:

“There’s a lot I could say about this film.”

“For some reason there are fewer great basso voices today,” I said. “The famous male opera singers are all tenors: Pavarotti, Domingo, Carreras.”

My father agreed: “Back in my youth there were cult basso singers in the Chalyapin mode: Mikhailov, Reizen.”

He recalled entering the evening branch of a musical college the same year when he started medical school. He stuck with it for about a year, studying voice. He used to know dozens of arias.

The following morning, right after breakfast, my father said: “I miss my computer.”

“That old legless robot?” I asked and immediately regretted it.

Later that day, after we took a morning walk to the Three Waters and what is locally known as the “Gatsby House,” we sat down in the garden and I pressed “record”:

MDS: “I’m amazed how you wrote the refusenik trilogy. You experienced an incredible creative upheaval, both in prose and in verse. How do you explain it?”

DSP: “I can tell you how. You see, all Soviet poets, even the most talented ones, always played this game, in which on their desk a cup of poison stood side by side with the sweet nectar of official court poetry. Which is why there were cases when I wrote weak and not very sincere poems. What is the point of poetry, of lyrical poetry, as I see it? It is in being absolutely honest with oneself. And so if you no longer look back and take cues … And as a refusenik I no longer looked back when I wrote. I only took cues from myself.”

MDS: “So you no longer looked to check the others’ reaction, right?”

DSP: “Yes, I no longer cared.”

MDS: “Tell me, Papa, when did you first start thinking about emigration? Not as a prospect of another person’s life, but as a real prospect for yourself. … Not that, say, Nabokov had emigrated, or another writer had emigrated, but for yourself.”

DSP: “Yes, I can tell you. After I was admitted to the Union of Soviet Writers, in 1976. … When I began to read my new work in public. I was invited with a group of people to the Spring Festival of Poetry in Lithuania.”

MDS: “This was in 1977, Papa.” (I went there with my father when I was about to turn 10.)

DSP: “And there I read only the poems I really cared for. … And especially ‘My Slavic soul in a Jewish wrapping …’ In this poem I expressed my soul and employed a new form.”

MDS: “At the time The Winter Ship had been finished, and you were trying to get the book published.”

DSP: “Yes, the Ship had some good poems, but not this one. … And then I understood: That’s it, I cannot do it. They are tempting me, like Satan tempted Adam, that I will be a successful poet-translator if I concoct a few conformist poems about my … how shall I put it … my relationship with Russia. And instead I began to write about Jewish themes. … I also told them I would now sign my work “Shrayer-Petrov,” that’s my literary name, and I won’t have it otherwise. Then they started putting my readings on hold, stopped commissioning translations. … Everything started coming to a halt. My poetry collection … [the book of ] stories for young readers. I came to a dead end and decided to leave. And so we applied for exit visas. Of course I couldn’t imagine the whole nightmare of emigration. I believe that, no matter what, it’s a nightmare for a Russian writer to emigrate from his native element.”

MDS: “But there are worse nightmares …”

DSP: “Yes, but to each his own nightmare.”

And to each his own stories, I thought, as I pressed “stop” on my recording device.

A few undramatic days went by, and then came the turning event of the summer. Even though scientists had been predicting that climate change would result in cataclysmic summer weather on Cape Cod, the local naysayers just shook their heads in disbelief, attributing it to the washashores’ inflamed imaginations.

On July 23, 2019, we had a tornado. It hit West Yarmouth, Harwich, and Chatham. Its path lay across the elbow of the Cape, right where we live. I was working at my summer office, a standalone little cottage, when it suddenly started. I grabbed Stella and I ran back to the main house, where my father was waiting in the dining room. It was Tuesday before noon. Mira and Tatiana were at Brewster Day, a back-to-nature camp where technology is frowned upon and the kids abandon cellphones before entering the grounds. It so happened that my mother was out shopping. Karen was in Boston, seeing patients at Boston Medical Center. Power went down, phone lines were overloaded. I had no luck getting in touch with my daughters’ camp office. I finally got a text from my mother that she was at a supermarket and it was on lockdown.

Then my wife got through: The girls were fine, they had taken them to a nearby church’s basement. In the meantime, we could feel the tornado fast approaching. It was too late to run to the cellar, and so my father and I stood, Stella shivering in my arms, and watched a waterspout descend, whirling and swarming, almost directly down our street as it veered toward our house. Old pine trees fell like broken matches. “It’s turning, Papa, take Stella and go to the bath hallway,” I screamed.

A huge spruce fell in the front of our property, just barely missing my car and landing between the pasture fence and the thickets camouflaging the neighbor’s back yard. An outdoor umbrella flew off the back porch and whirled around the lawn, like a frenzied ballerina. I was about to run out and try to close it when I heard a loud banging noise coming from the inner sanctum of the house. “Papa, Stella!” I yelled, frozen and glued to the dining room’s picture window.

My father was in the hallway, holding Stella’s leash with one hand and leaning on the wall with another. Frantically barking, the poodle pulled him toward his bedroom, whence the crashing and vibrating sounds emanated. A wind current blowing in my face, I pushed the door open. What I saw was stronger than life and stranger than fiction. My father must have left the front window open. As the tail of the tornado forced its way into the room, it ripped out the screen and unhinged the window. The bookcase toppled over, catapulting my father’s typewriter to the dresser, where she landed without breaking the attached mirror. Books were strewn on the floor, some having landed face down, others lying on their Soviet spines, pages aflutter.

“My Chekhov set,” I cried out.

“Chekhov will dry out,” replied my father’s voice from the hallway.

“Stella, it’s OK,” I tried to comfort the puppy, but she kept barking and trying to jump up on one of the twin beds.

And then the most inexplicable thing happened. Like the passing tornado’s aftergust, a stream of madly pulsating wind swept across the room. Breaking Olimpia’s case open, the wind picked up my father’s old typewriter from the dresser and sent her fluttering out of the room. Like a wondrous flying machine, Olimpia dashed past my father across the hallway, traversed the kitchen’s airspace, entered the dining room and came to a crushing descent. Plunking on top of the iPad, Olimpia smashed its glass, as if to assert itself as the chieftain of all writing devices. I stared in disbelief, first at Olimpia, then at my father, and finally at Stella.

We had survived our first tornado on Cape Cod. Broken limbs were scattered across the property. Fallen pine trunks blocked access to our street. The sky was leaden, and there was no power in the village of South Chatham.

At the head of the long dining room table, Olimpia the typewriter stood ready, triumphant. I took a sheet of paper from the printer, inserted it, and rotated the platen knob. I nudged my father to the chair. He sat down, glanced over the white sheet as though it were a mirror. Then he ran his shapely long fingers across the keys and grew pensive. I could feel my heart racing as time was moving backward.

I would have loved to tell you how over the next three days, as we lived without power, cooked eggs and boiled water for coffee on the gas grill, and played cards by candlelight, my father wrote a new story on his old typewriter. Except it wouldn’t be true. In fact, he was indifferent to Olimpia. We all tried to entice him. I would type a couple of lines and pass Olimpia back to my father. My daughters would try their hand at typing in their heritage Russian. My father only pressed his fingers to the keys but didn’t type. Looking at my father passing his fingers across the typewriter’s keys, I thought of my friend Petros Ovsepyan, an Armenian from Baku who can never go back to his home city. Petros now lives in Berlin and composes what he calls “silent music,” which musicians long to play but do not.

In early August my parents went back to Boston. My father told me on the phone that he was happy to be reunited with his computer, and he was slowly getting back into the novel he had been writing. A couple of days after their return from the Cape my father emailed me this about Olimpia: “Masik, I’d been dreaming about having a typewriter since the first year of medical school. You understand, don’t you? The aura of Hemingway and other journalists from the literary international. … Before the start of my second year my stipend had been raised [for top grades], and I bought my Olimpia for six hundred rubles. I dragged her around with me everywhere I went. She was my girlfriend. I took her everywhere. The Army … It happened that my Olimpia would catch a cold, and I made gogol-mogol for her. Actually, more details are in my memoirs …” I believe my father meant to say “in my fictions,” but I could be mistaken.

I closed the lid of my laptop and carried my father’s typewriter back to his room. “Don’t worry, sister, you’re safe,” I whispered as I returned her to her nook atop the Russian bookcase. “You’ll always have a home here,” I said and closed Olimpia’s time-beaten case.

Later that week Tatiana, my younger daughter, wrote a poem titled “My Grandfather’s Russian Typewriter.” It ends this way: “One afternoon I find it on the dining room table/Released from its case,/Buttons dusty yet ink still wet./I insert a blank page/And type awkwardly in Russian.” Tatiana included the poem in the manuscript of her poetry collection, which won second place at the 2019 Stone Soup contest and will soon be published as a book.

***

So how does this story of my father’s Russian typewriter end? It doesn’t, actually. When the editors of this magazine floated the idea of doing a piece about my father, I knew I couldn’t write a traditional journalistic profile. If I were to write about my father, it would be a personal story about an old Jewish Russian writer reflecting on his life’s vagaries, on his Soviet past and his American immigrant present. And thus we will end with Robert Frost, whose prophetic poem “Peril of Hope” my father has rendered so tenderly in Russian.

In August of 1962, Frost traveled to Russia. This was a year and a half after President Kennedy’s inauguration and over a year before the assassination. While visiting Leningrad, Frost met with Anna Akhmatova and gave a reading at the Pushkin House on Vasilievsky Island. My father attended the reading with my grandfather, Peysakh (Petr) Shrayer.

Frost’s performance affected them both deeply. A black-and-white portrait of Frost used to hang in my father’s Moscow den beside that of Boris Pasternak and a color photograph of Jackson Pollock’s “Blue Poles.” As a child, I heard from my father how Frost kept reading and reading, and what a giant of a person he was—in all senses of the word. My father has written about the 1962 Frost reading twice, first in a poem, later in a short essay. In Russian the Frost essay is titled “The American Classic,” and when my mother translated it for publication in an American magazine, the title changed to “The Towering Stranger Read On and On.” The poem about Frost shifts the perspective from the lyrical to the descriptive. The voice now addresses his father, then zooms in on the structural elements of the large Leningrad auditorium where Frost “speaks” his poems to a Soviet audience: “This, Papa, is a ceiling … This, Papa, is a podium …” For some reason my father doesn’t care much for this poem, whereas it moves me like a forgotten childhood song or a daguerreotype of an opera diva.

In early October, we returned to the Cape for the annual “mushroom-foraging” weekend. On Friday evening, my father, Stella the silver poodle, and I walked down to the Three Waters, where Mill Creek opens onto Nantucket Sound. Birds of sunset stood watch, blue herons like Picasso’s acrobats, egrets like sentries of exile.

“We’re here, Papa,” I said to my father. “We’ve become New Englanders.”

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.