My Favorite Anti-Semite: Frank Norris and the Most Horrifying Jew in American Literature

The progressive-era novelist’s greedy, red-haired, Polish Jew, Zerkow, is the 20th century’s greatest golem

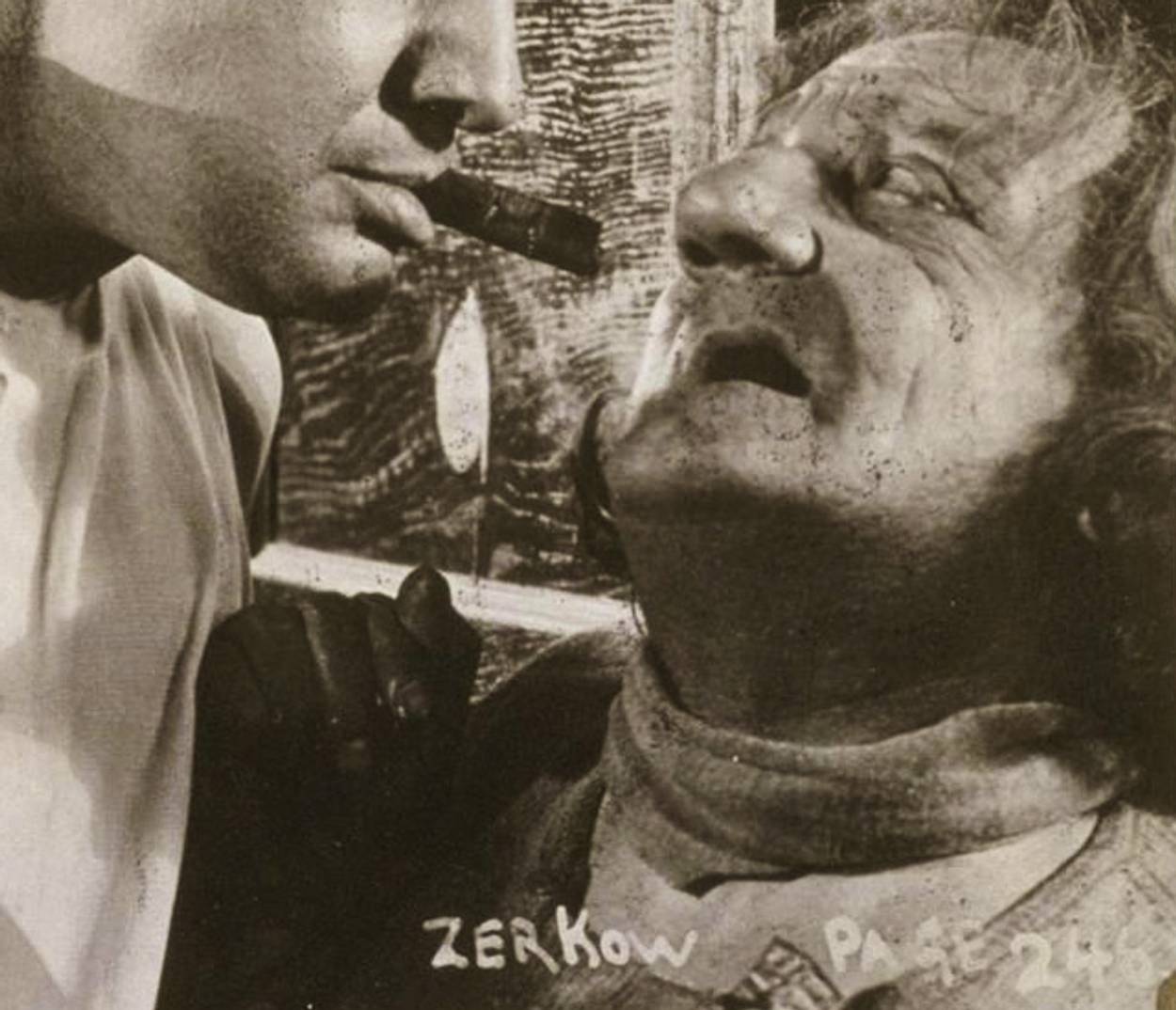

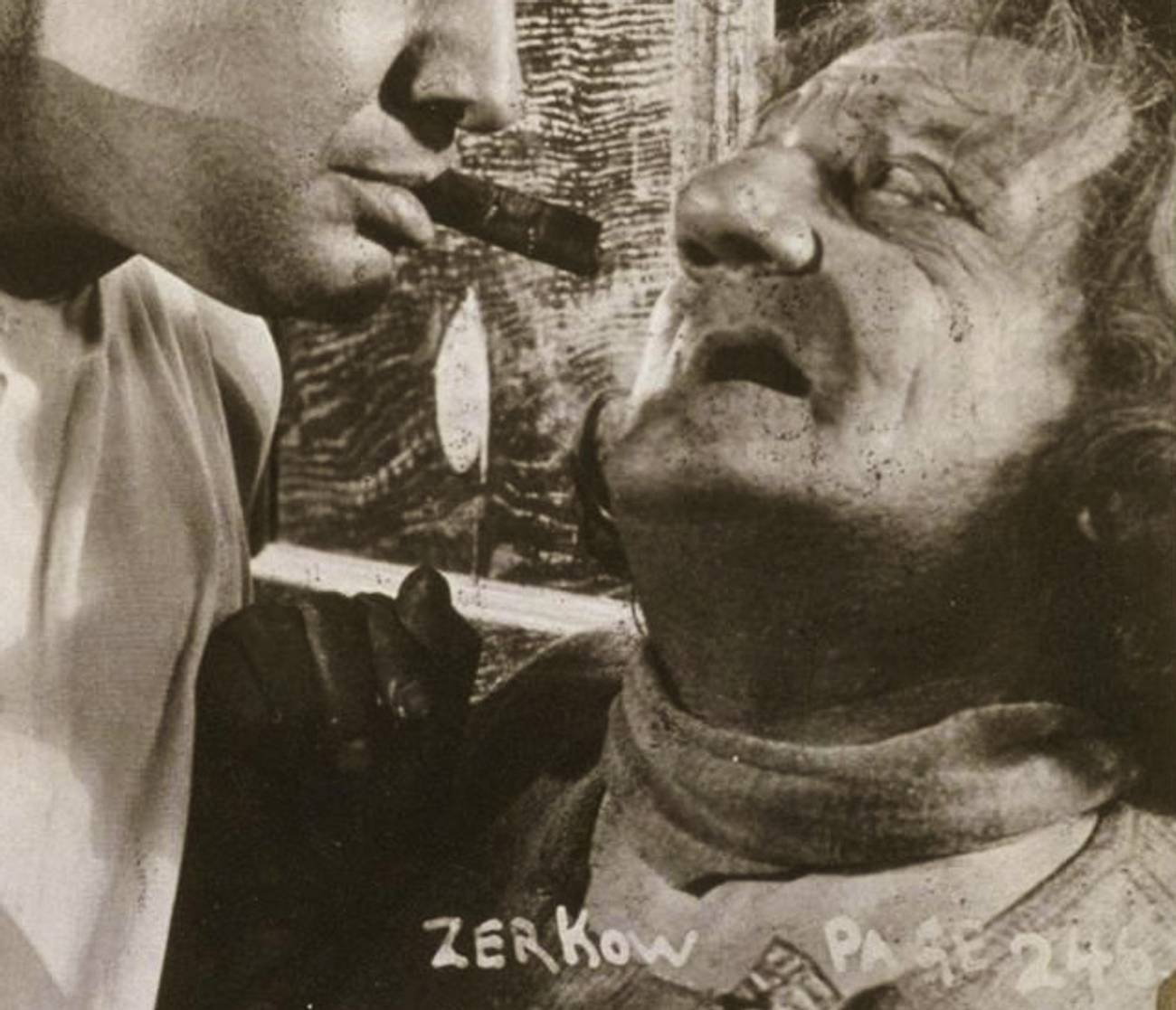

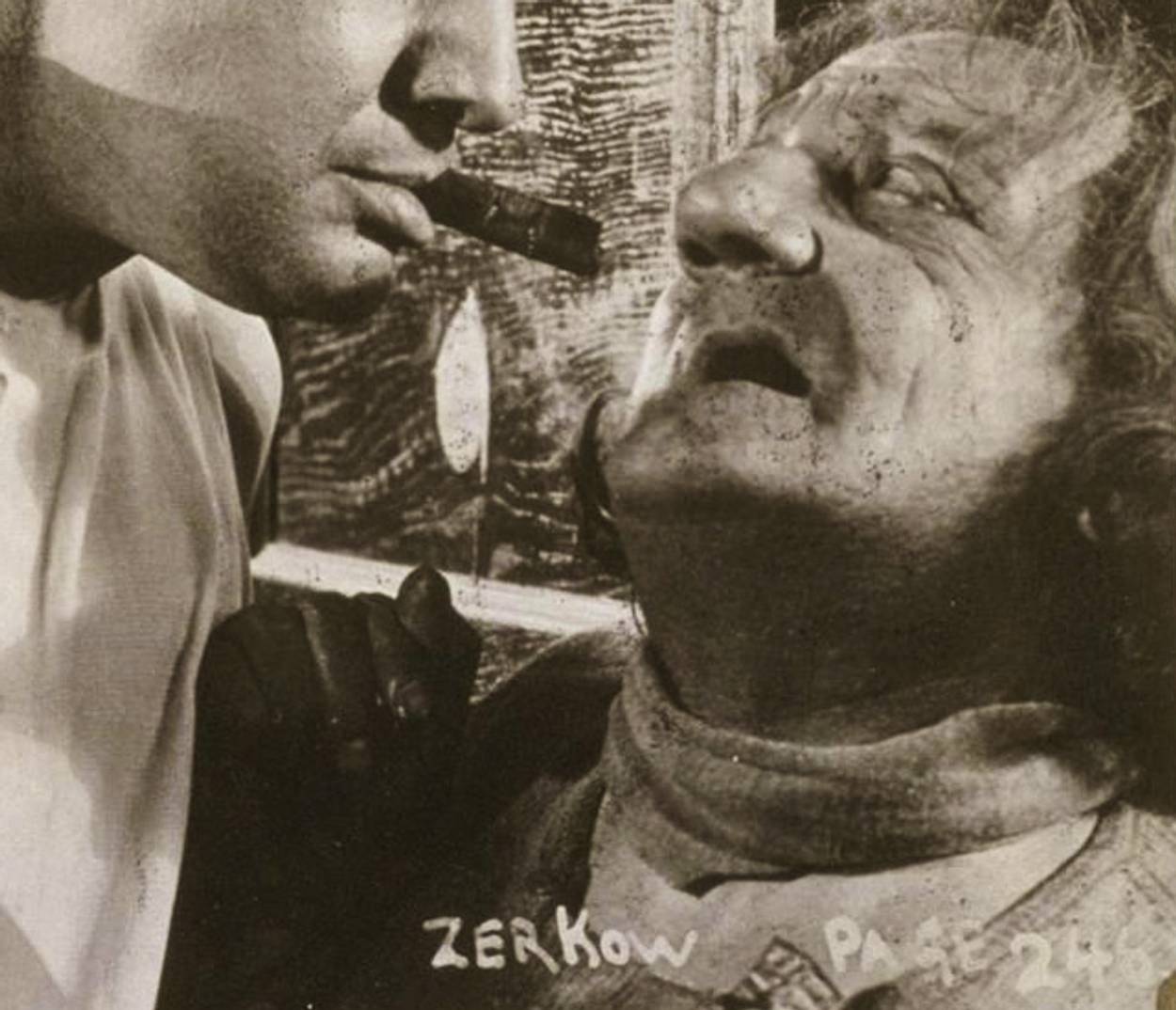

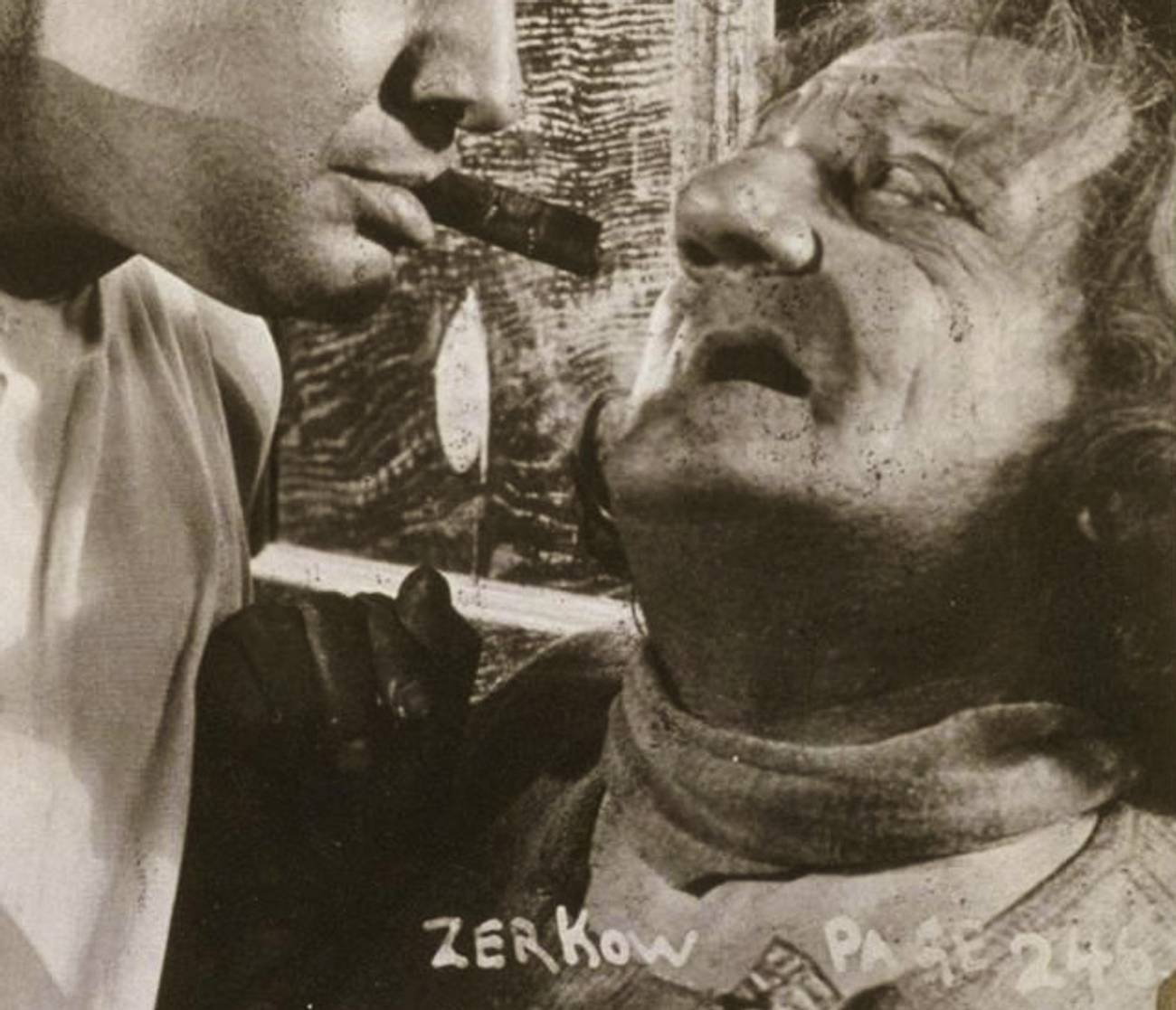

Search the American canon, early and late, for the most apparently anti-Semitic character in American literature and chances are your quest will lead you to a squalid San Francisco address not far from the Polk Street Dental Parlors where Zerkow—the junk dealer in Austrian director Erich von Stroheim’s 1924 film adaptation of Frank Norris’ novel McTeague—is engaged in his favorite activity: pleading, wheedling, and plying with alcohol the deranged charwoman, Maria Macapa. The crazy (i.e., Mexican) Maria pays regular calls to Zerkow’s stinking cellar for two reasons: to sell him the stolen filings of gold she has lifted from the competent if uncredentialed dentist John (Mac) McTeague; and to tell, again and again, the tale of a gold dinner service, one hundred lustrous pieces, that her family once owned. Zerkow, a “dry, shriveled old man of sixty odd” with the “thin eager catlike lips of the covetous” and “the fingers of a man who accumulates but never disburses,” relishes the sight of the gold scraps, but he loves even more to hear, again and again, and yet again, the tales of the gold dinnerware service, which he will eventually make his own.

This was one of two main sub-plots in the film version, titled Greed, that were later cut by David Selznick, but both were preserved complete in von Stroheim’s 300-page screenplay, which is meticulously faithful to Norris’ novel. Greed’s protagonist is the wife-abusing, eventually wife-murdering alcoholic blond behemoth McTeague. A product of Darwinian evolution, McTeague is a great Scots-Irish animal uneasily installed in the modern world. Once a gold miner, McTeague has refined the large muscle skills he used digging and extracting ore from the earth into the small motor ones he needs to practice dentistry. Self-taught, McTeague nevertheless has gained a foothold in urban life, and he even shows evidence of abstract thinking—as when he purchases a gargantuan gilded incisor to hang outside his Dental Parlors. (Stills from von Stroheim’s original cut show a tooth as large as a Mini Cooper.)

McTeague’s wife, Trina—for a time, the love of big Mac’s life—is a thrifty little Swiss who spends her time wiping the oilcloth, hanging housewifely curtains, and supplementing the dentist’s income by decorating toy Noah’s Ark animals with nonpoisonous (translate: VERY poisonous) paint. But Trina has a taste for speculative ventures and (being Swiss!) also a taste for squirreling away her gains. After Trina wins a thousand dollars in the lottery she becomes greedy and secretive. She is then often to be found of a night lolling naked in beds full of gold coins, eyes rolling back in her head. Trina keeps money from Mac, and after he loses his dental practice, she refuses him money for the simplest needs; when drunk, he starts to bare his own incisors, using them to crunch on his wife’s knuckles. We know Trina is a goner when McTeague’s chomping releases the nonpoisonous residue into her bloodstream, necessitating amputation and auguring her eventual death. The film ends in Death Valley, where von Stroheim shot the final scene showing McTeague and his nemesis chained together in the alkaline waste with a useless bag of money between them: Greed!

As this summary suggests, Greed is so operatic and over the top that it sets the bar over which the Quentin Tarantinos of American film history are still vaulting. Lurid enough for the multiplex, the original uncut Greed would also have provided a complete exhibit of global anti-Semitism circa 1899, the nativists and the cosmopolitans, the genteel gentiles and the self-hating Semites, the Christian eugenicists and Zionists, the socialists and populists, and anarcho-communists, all making their contributions to one character—the red-haired Polish Jew, Zerkow.

To this day, students of the cinema still cherish hopes that the complete, uncut version will show up somewhere. While Selznick’s edit well may have consigned much in the way of cinematic genius to the ash can, it also eliminated an anti-Semitic subplot of such wide-ranging origins and such elite pedigree (American and European, conservative and radical, non-Jewish and Jewish Hollywood and Harvard) as to make the much more notorious racism of The Birth of a Nation seem provincial.

***

Scholars of American naturalism are right to emphasize that Norris’ depiction of the greedy Jew reflects a particularly American anti-Semitism that was very much of the 1890s and was shared by other naturalist writers. The so-called closing of the frontier, marked in Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1899 thesis, spelled to some an end to the classic era of national innocence and virtue. This literally golden era was being mourned at the time in various forms, some positive (the establishment of national parks!), some of more ambiguous value (the emergent national taste for ethnic humor), and some clearly negative, among which one would have to count the Free Silver campaign advanced most famously by three-term presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Free Silver’s aim was to free the Christian heartland from Eastern bloodsuckers who sought to “Crucify the working man on a cross of Gold.” Bryan’s Free Silver campaign derived much of its popularity from xenophobic grafting of robber baron excesses onto immigrant (Jay Gould sounds Jewish, doesn’t he?) monsters. To wit: Zerkow, “the man with the Rake, groping hourly in the muck heap of the city for gold, for gold, it was his dream, his passion; at every instant he seemed to feel the generous solid weight of the crude fat metal in his palms; the glint of it was constantly in his eyes; the jangle of it sang forever in his ears as the jangling of cymbals.”

Like the targets of Bryan’s ire, Zerkow has an immoderate, salacious love of real, genuine gold. But, as the story of Maria’s dinner service suggests, he also traffics in the ersatz and enlarges himself by manipulating fictive financial instruments. If the ka-ching of gold is Zerkow’s eternal and singular obsession, Norris’ imagery of “instruments” (developed across the novel) contrasts legitimate and illegitimate instruments of value. Workman’s hand-tools—including Mac’s dental tools and miners tools—lose their utility, as more symbolic instruments of manipulation (political, sexual, linguistic, and especially economic) disempower honest workers. The once-powerful American Bunyan, who crossed the prairies and mountains and harvested their natural riches, is now stranded on the edge of the continent, vulnerable to the coastal elites—(feminized) Jewish conspirators and their foreign (Swiss) co-conspirators. What use is the frontiersman’s manly brawn in a world where value is stockpiled in vaults, where success is controlled by those who traffic in arcane paper—in lottery tickets and installment instruments, in rents and leases and contracts bonds, I.O.Us and licenses?

Though dumb as a post, Mac cherishes true things (his perceptions, his appetites, a few precious, irreplaceable belongings) while Zerkow can’t tell trash from treasure. We see this when, maddened by gold lust, Zerkow takes over the fantasy of the gold dishes, getting so aroused by Maria’s, and then his own, recitations of the story that it makes his “breathing short, and his limbs trembling”; we see “his bloodless lower lip moving against the upper … his clawlike fingers feeling about his mouth and chin.” A eugenicist’s nightmare—a one-person argument against indulgence of sexual instinct for nonprocreative purposes and a one-man demonstration of the dangers of promiscuous (as opposed to selective) breeding—Zerkow does marry Maria, but the marriage is worse than sterile. When the couple actually has a child, “combining in its puny little body the blood of the Hebrew, Pole and the Spaniard,” its birth—and subsequent death—clears Maria’s head of her nostalgic fantasies. Zerkow then kills his wife by slitting her throat; he is later found himself drowned in the bay, with 100 pieces of junk tied to his body.

Mac kills his wife too, but being Scots-Irish, rather than Jewish, he tumbles down a different devolutionary chute. His own reversion to bestial murderer, though inevitable after his violent nature is roused, is interestingly gradual. For instance, he passes through a stage when he spends a lot of time outdoors, taking long walks, hiking and fishing in the cleansing bay fog. These walks remind us of those benign and vital aspects of the natural life from whose cleansing virtues he is barred by urban corruptions (in his case, corner barrooms). Of course, taking a nice walk is, not incidentally, of a piece with Norris’ Nob Hill strain of naturalism—whose minuses include turning unlicensed dentists into raving maniacs but whose pluses are of a kind any red-blooded American boy could understand.

***

Norris himself was such a boy. Born in 1870 to a wealthy Chicago businessman who moved the family West, the young Benjamin Franklin Norris had a taste for strong “reality” that was nurtured as part of his genius. After suffering a football injury at boarding school, Frank was brought home for tutoring and then sent to study art in Chicago, London, and finally Paris, where he got his first exposure to the work of Emile Zola. His juvenile researches into medieval armor (manly topic, that) and an epic poem, also penned in Europe, resulted in his very first publications, when his mother submitted the study of armor to The Wave and then subsidized the poem’s publication in Lippincott’s Magazine.

It must therefore have come as a shock when the prodigy’s admission to Berkeley in 1890 was compromised by his inability to pass the required mathematics exam. But the University of California was prevailed upon to admit Frank provisionally, and it is there, signed up for the “Literary Program,” that Norris was able to immerse himself in the post-Darwinian and positivist studies of culture that would influence all his subsequent writing.

Among Norris’ teachers was the charismatic, Harvard-trained Christian evolutionist Joseph Le Conte. An energetic promoter of cheerful social Darwinism, confident that God’s plan provided for the triumph of the fittest, Le Conte, the Sierra’s Club’s first president, was a perfect mentor for his Nob Hill naturalist student. Norris’ contempt for soft moral categories, for sentimental notions of free will and moral choice, and his preference for hard positivist fact did not, however, aid him in passing the math exam requisite for Berkeley graduation, but luckily there is a more enlightened university, one ready to help him complete his studies: Harvard!

Installed in 1894 in Grays, then Harvard’s plushest dorm (the first to have running water; students in other accommodations hauled their water from the pump in the Yard), Norris enrolled not in Math but in Creative Writing courses, and in a single year of frenzied composition drafted not one but two novels based on his four years of applied study at Berkeley. The first, Vandover and the Brute, is based at least in part on research Norris was able to pursue as a Phi Gamma Delta brother, the rigorous after-hours curriculum pursued by college “sports” like Norris giving authenticity to what amounts in the novel to a complete and accurate atlas of San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Norris’ second project is McTeague, a story not only of sex but of other drives, like greed. Fictionalizing the social Darwinist doctrine he absorbs at Berkeley, Norris wrote his novel of San Francisco as a demonstration of the struggle for preeminence among the races, each with their assets and debilities: the blond giants of Northern Europe, with their native heroism and just as native liability to violence; the middle Europeans, like the Swiss, with their intrinsic gift for domestic order and their just as intrinsic gift for concealment; the Latin races, with their sentiment and mad grandiosity, their gift for conquest and defeat—and then, finally, the Jews, coastal and puny, clever and greedy, grasping and lewd.

***

It would not be accurate, however, to blame Zerkow entirely on homegrown American gentile anti-Semitism. All manner of restive young Europeans, among them a great number of European Jews, were working hard to apply the findings of Darwinian science to social conditions in the 19th-century city. Uniting them all was an interest in, and attitude of strict fidelity to, the brute facts of human development. These glatt cosmopolitans, as we might call them, demanded facts as ugly as reality demanded, and they showed a particular partiality for facts that their traditionalist parents were likely to find most distasteful. Von Stroheim, the son of an observant Jewish hatmaker, though he styled himself a German aristocrat, was on the younger end of that fin de siècle generation of middle European Jewish sons fed up with the makeshift compromises of their barely emancipated fathers. What von Stroheim loved about Norris and sought to capture in his own work was “men and women as they really are all over the world … their good and bad qualities … their noble … and their vicious, mean and greedy sides.”

Max Simon Nordau, of von Stroheim’s Vienna, influenced Norris as well, and he as much as any writer of the 1890s contributed to the portrait of urban persons, not excluding urban Jews, as “degenerates.” Nordau, whom some may know better as Theodor Herzl’s best friend and first president of the World Zionist Congress (and a man after whom every city in Israel has named a square), established his international reputation with the provocatively titled Degeneration of 1892. The book traces the fearsome modern syndrome of his title to the poisons of urban life: “The inhabitant of a large town, even the richest … breathes an atmosphere charged with organic detritus; he eats stale contaminated, adulterated food.” The effect of life in a large town is the same “fatality of degeneracy and destruction as the victims of malaria.” If Nordau slaps the title “Degenerate” (a title later, tragically, ironically, useful to Nazis) on Wagner, Nietzsche, and Zola as well as many of his own co-religionists, the fact that he was raised a rabbi’s son does not keep him from adumbrating the ways in which urban accommodation has sapped Jews of their masculinity. As Le Conte is to the Sierra Club, Nordau is to the kibbutz: He coins the term “muskel-Judenthum” and in this and many other ways influenced Herzl, who presents his own cautionary portrait of the puny, compromised Jew in his 1894 Das Neue Ghetto. Ashamed of petty commerce and social climbing, enamored of culture and ready to break family china (milchigs and the fleishigs be damned), the young Herzl sought in the vanguardism of the arts and the rigors of intellectual discourse a means to sweep away the taint of trade and the mustiness of accommodation.

By the time of his manifesto, The Jewish State, Herzl is accentuating the positive—but between Herzl’s stereotypes and Norris’ Zerkow are not as many degrees of separation as we might prefer. The Jewishness of Norris’ naturalism is even more striking when we consider how deeply the American novelist plunged into the more colorful research of Nordau’s other best friend, the Italian Jewish doctor and criminal anthropologist Cesare Marco (Hezekiah Mordechai) Lombroso—the fruits of whose positivist inquiries in the form of callipered skulls, measured brains, and elaborately analyzed photographs of the heads of criminals are now preserved in the Museum of Psychiatry and Criminology. One sees the stamp of Lombroso all over Norris’ treatment of his non-Jewish criminal McTeague, with his wolverine jaw (the better to crunch your knuckles, my dear) and great “square cut” empty head, padded with five inches of blond mattress stuffing (big hair plus big skull equals surplus animal tendencies). If skull measurements and such left Lombroso especially impressed with the ways a Scots-Irish like McTeague might be a born criminal, he also took a dim view of the genetic potential of the urban Jew: “The Jew in large Jewish centers, particularly in the East, is usually small and fragile, his appearance ruinous and wretched. … The habit [of making deals] has been so intensive and has continued for so many years that it has emphasized their habit of cunning and falsehood, the meager muscular energy so prevalent among merchants.” Meanwhile, Lombroso’s researches into deceit in women, a failing he correlates with childlessness, probably also helped Norris to develop parallels between the unmanly but also lewd Zerkow, who gets off on tales of gold, and the childless Trina, who literally orgasms in beds of money. Norris would have had—and probably did have—help there too from the burgeoning literature of the American Birth Control movement. The sainted Margaret Sanger’s efforts to help women limit their families may have epitomized the forward thinking of what would become modernism’s avant-garde, but her campaigns for contraception and against unlimited families drew inspiration and vocabulary from eugenics. It’s no accident her campaign to establish birth control in America began in Williamsburg, among Yiddish-speaking Jews.

Lombroso might not ever find the place in the liberal pantheon reserved for Margaret Sanger. But like his contemporaries, Norris, by most accounts, was a liberal thinker. His fidelity to “realities,” however lurid, presaged the clear-eyed attitude to injustice a next generation would fashion into progressivism—and the artistic fearlessness that a next generation would name modernism. In recognition of their own high tolerance for representational extremes, and their deliberate fearlessness about upsetting social apple carts, such 1890s pioneers as Max Nordau, Cesar Lombroso, and Theodor Herzl; Le Conte and von Stroheim and Frank Norris, too, all deserve our interest today. The Zerkow they all joined together to produce is as instructive an anti-Semitic golem as the 20th century produced.

Elisa New is the Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature at Harvard.