Message From a Yiddish Werewolf

A 1920s epic poem about fear, and Jewish vulnerability, that could have been about 1944—or 2018

There is no such thing as reading for its own sake. When we read stories and poetry, whether we intend it or not, we are searching for ourselves in those works, for answers to our own most pressing questions. That doesn’t mean we are solipsistic readers. It means we are readers, people who believe in a shared human experience. Literature is communication, a profound message gifted to us from across space and time, one whose value lies in its resonance right now, to us.

Which is why, after the recent massacre of Jews in a Pittsburgh synagogue, I’ve been rereading an epic Yiddish poem that has haunted me since I first encountered it more than 20 years ago. It is about surviving a massacre, but it is really about the disfiguring and inexpressible fear that comes afterward. It was written by an American who was considered the greatest Yiddish poet of the 20th century, and it is titled “The Wolf.”

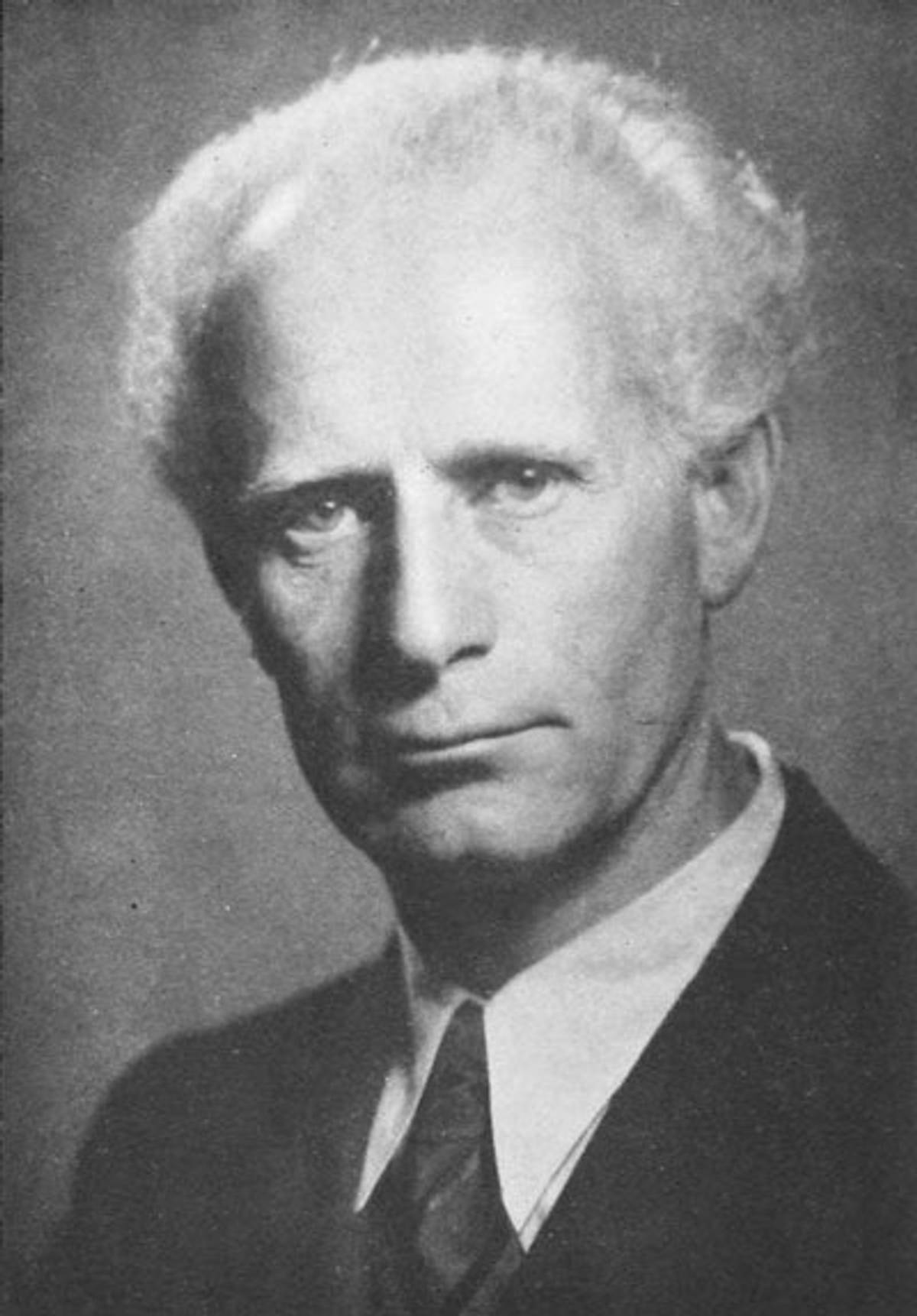

The poet H. Leyvik (pen name of Leyvik Halpern) had the kind of life that would make for maudlin fiction. Born in 1888 in today’s Belarus, Leyvik grew up in a two-room, dirt-floored hut with his mother, his eight siblings and his abusive father. If that weren’t fun enough, he soon decamped for the life of a yeshiva student, which involved an existence comparable to homelessness—sleeping on synagogue benches and “eating days,” the Yiddish term for a board system where community members took turns hosting students for meals. The success of this system is perhaps best illustrated by the leg wounds Leyvik sustained as a result of starvation during his yeshiva years.

Leyvik became a revolutionary activist before he was out of his teens. In 1906, he was arrested and sentenced to four years in prison, followed by exile in Siberia for life. Leyvik spent those four years in shackles, often in solitary confinement, a period during which he wrote his first epic poem, “Messiah in Chains.” (He was not a particularly humble man.) Siberia was hardly a relief, as he was forced to travel there on foot while still in chains.

The journey took four months. Once arrived, he made contact with some revolutionary friends who were able to assist him in escaping. He journeyed by horse-drawn sleigh back across Russia, and at last boarded a ship to New York.

Renouncing Communism after Stalin’s pact with Hitler, Leyvik became an outspoken and deeply respected figure in American Jewish life, and continued writing until a few years before his death in 1962. His poetry was grandiose and glorious, evoking ancient Jewish legends and applying them to his own dramatic life and the lives of his Jewish readers.

When I first read “The Wolf,” I kept turning back to the copyright date, astounded that its story of a sole survivor amid heaps of ashes wasn’t about the Holocaust. It’s not. Written in 1920, the poem (or “A Chronicle,” as its subtitle proclaims) makes it clear that the Holocaust was merely an exponential expansion of previous massacres. This episode of mass murder was the Petliura pogroms, which swept through Ukraine in 1919 during the Russian Civil War and involved the slaughter of a “minimum credible estimate” of 50,000 Jews, according to the YIVO Encyclopedia.

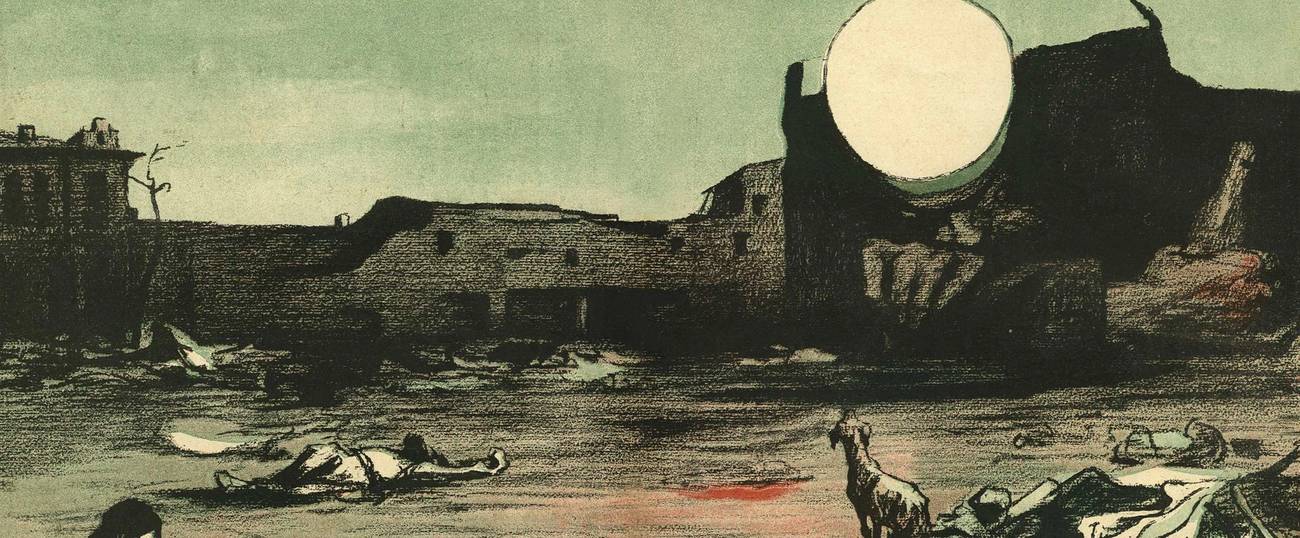

“The Wolf”—available in Benjamin and Barbara Harshav’s anthology American Yiddish Poetry, whose translation I quote here—opens with a solitary figure, known only as “the Rov” (rabbi), awakening from unconsciousness on a mound of ashes to discover that he is the only person left alive in his destroyed town. He wanders the smoldering landscape searching for other survivors, then for perpetrators, then for corpses, and then even for body parts to bury. But the victors have left, all human remains have been torched, and, as the poem keeps repeating in a haunting chorus, “the Rov did not know what to do.”

The Rov finally removes his shoes and begins to recite Hebrew laments traditionally sung to commemorate the Temple’s destruction, a central ritual of communal Jewish mourning, but “he had forgotten the words of the laments.” He then attempts to recite the daily prayers, but “he had forgotten the words of the prayers.” As night falls, he flees barefoot into the “forty-mile forest” surrounding the town.

That’s where things get interesting. Caught in a snarl of barbed wire in the woods, the Rov somehow loses his clothes and falls onto all fours, and his transformation begins. Naked and struggling, his body sprouts hair, his fingers fuse and grow claws, his neck and shoulders merge, his teeth grow sharp, his lips droop, his eyes glitter, and he howls out his pain. When this Jewish werewolf emerges from the forest, things get even worse.

Back in the destroyed town, Jews expelled from other areas move in and rebuild. Dedicating their repaired synagogue, they are celebrating their renewed life in this desolate place when they hear “a long drawn-out howl of a beast” in the distance: “At first, angry and roaring, as in a moment of devouring prey, / Then thin and desperate, as the wailing / Of a dog baring his heart to the moon, / And finally, quieter and quieter and whining, / Like the cry of a human being.”

The nighttime howling terrifies them, but more horrifying is the appearance of a stranger the next morning in a rabbinical coat and fur hat. At first they hurry to greet him, hoping he will replace their own murdered Rov. But soon they see that he is bare-chested and bloody beneath his coat, his feet bare and his face sunken. He enters the synagogue and takes the Rov’s seat beside the eastern wall. And then he speaks, railing at them for rebuilding the ruins. Soon he falls at their feet, begging them to kill him. They crowd around him in sympathy. That’s when he bites someone’s hand. The congregants flee.

Each night, the howling continues, until suddenly, on the eve of Yom Kippur, it ceases, without anyone connecting the sound to the Rov. The congregation rejoices, relieved. But at the very end of Yom Kippur, at the shofar’s final blast, the “wolf” enters the synagogue and attacks the prayer leader. At that, one congregant takes a wooden lectern and smashes his skull. The entire congregation then pummels him until he lies dead on the floor—“And the congregation burst into great weeping / For on the floor, tortured, in a river of blood / Lay not a wolf but a Jew in a rabbinical fur hat.”

When I first encountered this poem years ago, I was riveted by the Rov, whom I understood as a person disfigured by trauma. The poem, I thought, was a call for empathy for survivors, and a warning about how “hurt people hurt people”—though the latter idea in this context felt false to me even then, a cheap After School Special idea about “prejudice” that was untrue to the survivors I knew, and also untrue to the poem itself (where only the Rov winds up dead).

But after the Pittsburgh massacre, I read this poem differently—and, I suspect, in a way much closer to how American readers in 1920 may have read it. Insert here all the insultingly obvious caveats about how a lone gunman murdering 11 people in no way resembles 50,000 dead. Those caveats don’t matter for this poem, because this poem isn’t about history. It is about fear.

The poem, as I now understand it, isn’t really about the Rov, whose point of view hardly figures in the work. It’s about the other Jews, whose shared emotions are intimately described—and all too familiar. These Jews rejoice in their survival, but they are also haunted by the horrific fact that other Jews have been murdered while they have randomly been spared—the defining fact of post-Holocaust American Jewish identity. The wolf’s presence in their midst is an embodiment of that haunting, the deep awareness of total vulnerability that lurks just beneath the surface of their daily lives.

Leyvik tells us as much. As the poem’s Jews listen to the wolf’s midnight howling, “they could not hear a thing anymore / Except the beating of their own hearts.” Later, as the howling grows louder and closer, “in each turn of the voice was heard / A hidden challenge, an appeal, and above all, a pleading; / Which chilled their hearts more than anything, / For it reminded them of the cry of a human being.” This disfigured beast crying for mercy is inseparable from who they are. It is part of them, one of them, the buried part of thousands of years of pain. They want that wolf to go away, but they cannot kill it without killing themselves.

After the Pittsburgh massacre, I wrote a piece for The New York Times about how different this attack was from others in Jewish history—how first responders hurried to help, how support poured in from neighbors and strangers, how non-Jewish Americans stepped up to announce that this is not what our country is. Many readers thanked me for giving them hope. But what stunned me was how many Jewish readers wrote to me privately, doubting that I was right. Deep in their bones where reason cannot reach, they heard the wolf at the door.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Dara Horn is the award-winning author of five novels and the essay collection People Love Dead Jews.