I Dream of Lansky: The Dead Jewish Mob King Rules Zachary Lazar’s Law-Bending Novel

At the intersection of artifice and experience comes a beguiling fantasia on Jewish themes, ‘I Pity the Poor Immigrant’

A hundred years ago, a gifted young storyteller aspired to write the Great American Novel; today, she is more likely to want to put her gifts to use writing a memoir, or a collection of autobiographical essays. (When the Lena Dunham character on Girls declared that she wanted to become the voice of her generation, it was by writing first-person essays.) This has been the case for at least the last 15 years, and by now we are used to both the memoir craze and the backlash to the craze. Too often, we know, memoirs can be manipulative, self-aggrandizing, or downright made up—the name James Frey stands for a whole moral case against the genre. At their worst, memoirs illegitimately trade on our sympathies, asking us to pity or admire the person we are reading about, rather than the writer who is doing the literary work. They shortcut judgment, including aesthetic judgment, and promise to take us straight to the truth—making them alluring to a reading public that sees fiction itself as unnecessarily demanding, morally frivolous, or simply beside the point.

More interesting, however, is the case of genuinely talented writers who choose memoir over the novel, fact over fiction, on specifically literary grounds. Writers like John Jeremiah Sullivan or, just recently, Leslie Jamison—whose essay collection The Empathy Exams I haven’t yet read, but which is being rapturously received—are just as serious and probing as you might want a novelist to be, but they thrive by wrapping their narrative imaginations around a core of fact. They are writing not just about themselves, the way bad memoirists usually do, but about the world they encounter. And when you read this kind of nonfiction done well, it is easy to feel that fiction itself is too formulaic, too complacent in its inventions of plot and character, to do justice to reality. Even proficient fiction can feel too insulated, too much a self-pleasuring exercise; why not go straight to the source, to reality itself?

Who will vindicate the novel in the face of the memoir’s commercial and literary claims? Who will prove that the techniques of fiction can give us all the dangerous charge of reality, and more—that fiction can actually get deeper into reality than memoir, which has its own set of conventions and blind spots? The answer is that the best fiction of the last generation, the most genuinely compelling, is deeply engaged with just this question. Writers as different as Teju Cole and Sheila Heti flip the usual equation: Instead of writing memoir that is as suspiciously fluent and shapely as fiction, they write fiction that is as odd, angular, and challenging as reality. It may be that the intersection of artifice and experience is the only place where the contemporary novel can really thrive.

Zachary Lazar is one of the contemporary writers who work at that intersection. His acclaimed 2008 novel Sway used real-life 1960s figures, including the Rolling Stones, as characters in a story of that decade’s violent underside. Then his memoir Evening’s Empire tried to reconstruct the true story of his father’s murder, along with the whole world of petty criminality in which it took place. Both books were praised—or, depending on the reviewer, condemned—for turning the mechanics of storytelling inside out, foregrounding the way the writer imagines his way through the gaps in the evidence.

***

In his new novel, I Pity the Poor Immigrant, Lazar has brought this same constellation of concerns to a totally different story—one that blends real-life figures with invented characters. I Pity the Poor Immigrant is a kind of fantasia on Jewish themes, covering everything from the State of Israel and the Holocaust to the Bible and the immigrant experience. Its presiding spirit is Meyer Lansky, the Jewish gangster who made a failed bid to escape American criminal charges by moving to Israel. But the central concern of the book is specifically literary: It is an expression of disgust with memoir, of exhaustion with the whole idea of a coherent, narratable self.

That disgust is felt strongly by the book’s main narrator, Hannah Groff, who resembles Zachary Lazar in having written a memoir about the criminal background of her own father. Right from the start, Hannah—“close to forty, divorced, without children, not unhappy but not what anyone would call ‘settled,’ a person in transit”—tells us that she is tired of writing about herself, that she is no longer sure she has a “self” to write about:

I once said in an interview: “What we need is a memoir without a self. A memoir about somebody other than ‘me.’ An understanding that the story of other people connected to ‘me’ might communicate more than the usual ‘me,’ might show the cultural context of ‘me,’ might even cast doubt on the viability of ‘me.’ ”

Lazar suggests that this kind of alienation, this displacement of the self from its usual place at the center of consciousness, is analogous to the experience of the immigrant. “In writing this book,” Hannah explains, “I have come to feel like a kind of immigrant in my own life, inhabiting a world of reflections and images of people I can’t fully know, some of whom are dead, and I see now that my life has been shaped by this network, in ways that I didn’t always perceive.”

This is the essential context for understanding Lazar’s title. For him, the immigrant who is to be pitied is not just someone who changes countries, but someone who undergoes eviction from her own life. To convey this feeling, Lazar uses a technique of fragmentation and montage. The narrative proceeds in short sections, skipping from one time and place to another, in a kind of ostentatiously neutral, even anesthetized prose. Only gradually does the cumulative design of I Pity the Poor Immigrant become clear, and that design is less a plot than a map, with different locations connected by tenuous routes.

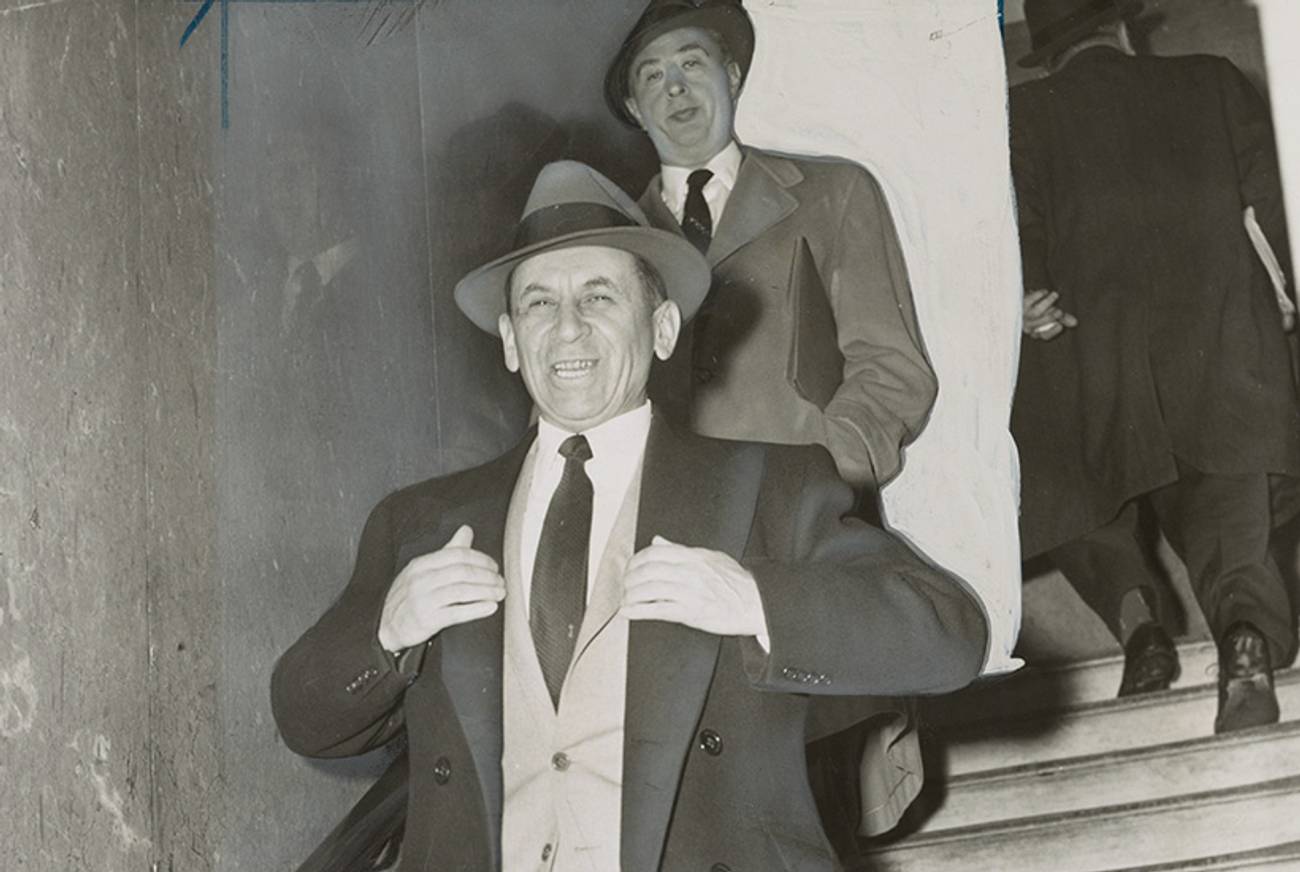

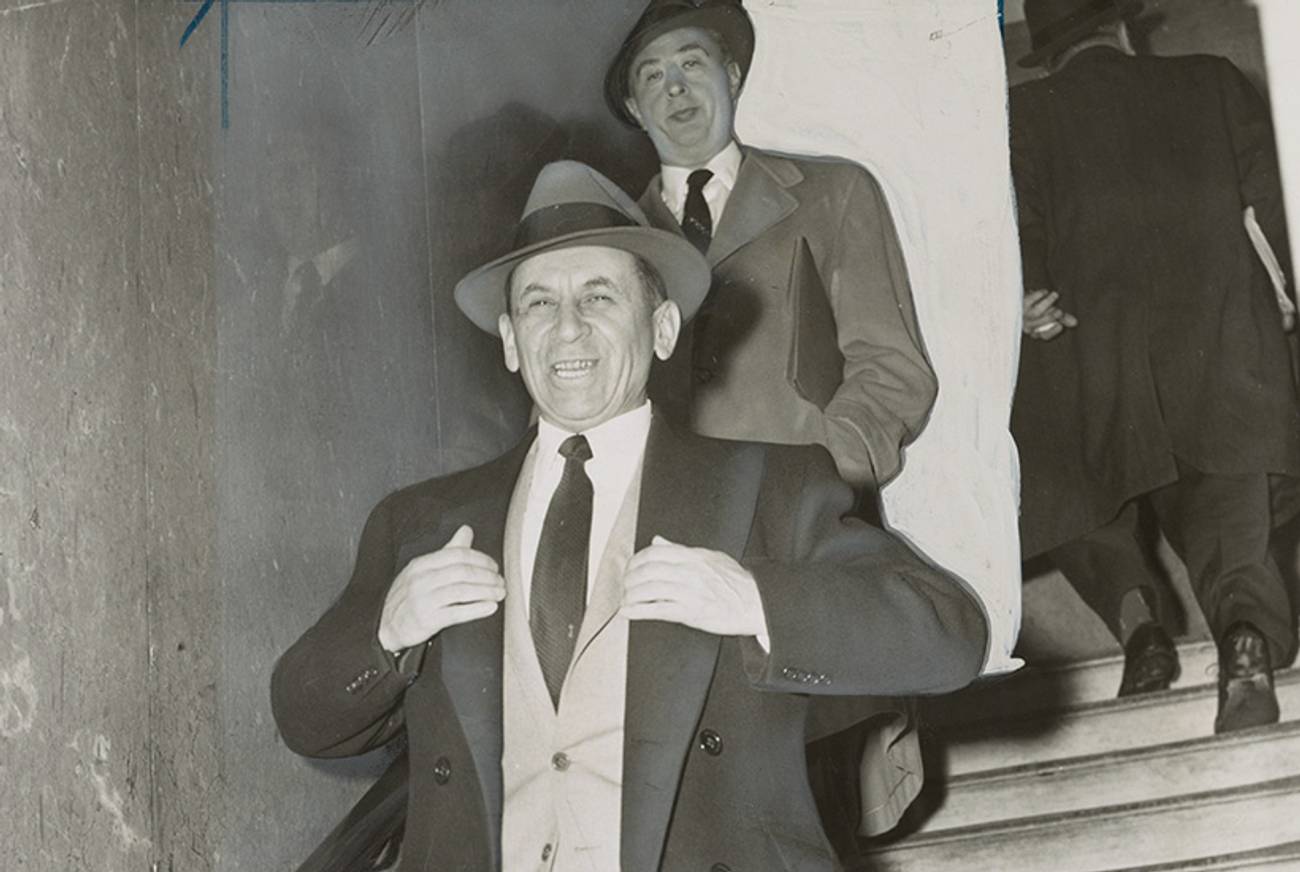

At first, the center of the map seems to be Meyer Lansky, who is the only real-life figure among the book’s major characters (though others, like Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano, make cameo appearances). When we first meet him, Lansky is living in limbo in Tel Aviv, waiting for an Israeli court to rule on his petition for citizenship. As Lazar conjures him, however, Lazar is no folk legend or criminal mastermind. Rather, he is distinctly smaller than life, an old man out of control of his destiny, an immigrant:

Gangster, racketeer, mobster—she could not get the words to adhere to the physical person. Not that she disbelieved the stories, but the stories’ language glared, whereas the truth of him resided in understatement. The gray trousers and the pressed shirt, white linen or pale blue linen. The leather shoes and the Herald Tribune. Everything important was invisible, maybe glimpsed for just an instant when he turned to her in a certain way and his accused her of looking too closely.

The woman who is doing the scrutinizing here is Gila Konig, an Israeli cocktail waitress whom Lansky has picked up and made his temporary mistress. The year is 1972, and Gila, who spent her childhood in Bergen-Belsen and then a postwar DP camp, is in her early thirties—decades younger than Lansky. It is a relationship that cannot last or go very deep, which makes it fit in perfectly with the overall atmosphere of I Pity the Poor Immigrant, with its emphasis on personal unknowability. Indeed, when Lansky’s petition is denied and he is forced to leave Israel, it seems that his affair with Gila will leave no trace—except for the shabby apartment he rents for her, promising to pay the bills in perpetuity, as a kind of tip for the waitress who served him.

As it turns out, however, this affair, and even the apartment itself, will turn out to be spokes in a web that extends through time and space. The low-key surprises in Lazar’s narrative come thick and fast: Suffice it to say that Gila will end up moving to America, where her path will intersect with the young Hannah Groff’s in a life-altering way. And Hannah, who grows up to become a memoirist and journalist, ends up reversing Gila’s journey when she flies from New York to Israel, in order to write about a different kind of crime than Lansky’s.

This is the murder of a (fictional) Israeli poet named David Bellen, who has written a book of poems that imagines the biblical King David as a latter-day Tel Aviv gangster. Lazar gives us Hannah’s “article” about Bellen, which explains that his body was found mutilated in a West Bank village, the cause of death unknown. Was he killed by religious fanatics angry about his depiction of his namesake? Was his death connected with his son Eliav, a heroin addict well known to the criminals and drug dealers of South Tel Aviv? Or was it perhaps a suicide, made to look like a murder for insurance purposes?

Lansky, Gila, Hannah, Bellen—these are key figures in Lazar’s story, and they end up being connected in a multitude of unexpected ways. Bellen wrote a long essay about Lansky and the idea of the Jewish immigrant—another piece of concocted “found” prose that Lazar gives us. Hannah’s father turns out to be a crook of another sort, giving him a minor affinity with Lansky. The grown-up Hannah reencounters Gila, now aged and suffering from cancer, and begins to wonder whether the story of her affair with Lansky is true at all. In the end, everything seems to come down to that vacant Tel Aviv apartment that the gangster allegedly rented for Gila back in the 1970s—a place that is significant mainly because it is empty: “To stare in through the glass of its door was to understand insignificance not as a desert or a sea or a night sky but as nothing at all, a silence.”

Throughout I Pity the Poor Immigrant, Lazar plays on the Hebrew words “olim” and “yordim,” which refer to immigrants who have “gone up” to Israel or left it and “gone down.” In his hands, these become master terms that sum up our lives: The immigrant is someone who is always trying to ascend but finds himself declining instead. In this sense, you don’t need to change countries to be an immigrant: “Everyone is yored in the end,” Lazar writes. I Pity the Poor Immigrant is a paradoxical feat of a novel: a quiet pyrotechnic, full of elliptical insights, crowded with incident yet feeling lean rather than stuffed. It offers confident testimony that the novel, even in the age of memoir, has its own irreplaceable role.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.