Michael Chabon’s Apollo Mission to the Past

The new Moonglow is a novel in the form of a memoir, a superhero comic in the form of prose, and a paean to the fading Greatest Generation

The term “the Greatest Generation” has been around for 20 years, but the members of that cohort—Americans who grew up in the Depression, fought World War II, won the space race and the Cold War—are now gone, or are going fast. And as they go, the temptation to mythologize them becomes harder and harder to resist. This is especially true, perhaps, for American Jews, who see in their grandparents certain virtues—of toughness, worldliness, practicality, and pride—that are in short supply among later, richer, and softer Jewish generations. Of course, the past always seems more authentic than the present. But there is no doubt that American Jews born in the 1920s had a harder destiny to cope with than Jews born in the 1950s or 1980s. (Whether this trajectory toward greater ease and acceptance will continue into the 21st century is, sadly, an open question.)

In Moonglow, his brilliantly imaginative and entertaining new novel, Michael Chabon has written his own tribute to his grandparents’ generation. Chabon is a born teller of tall tales, with a gift for heightening. It makes sense that in his best-known book, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, he wrote a parable about the American Jewish invention of comic-book superheroes, because his own heroes are always about 50 percent larger than life. Indeed, one way to think of his books are as graphic novels in prose, in which hypervivid metaphors do the work of line and color. Such little bursts of verbal magic occur on virtually every page of Moonglow: “He reran the grainy kinescope of memory”; “one sometimes sensed a weird crackling around her, a scorching like dust on a solenoid”; “he switched off the Zeiss [telescope] of his imagination.” Chabon is so profligate with these conceits that his writing can seem antically clever, but that doesn’t mean it is show-offy or insincere. On the contrary, like a good graphic novelist, he uses stylization and exaggeration to create the large emotional effects his story requires.

The story of Moonglow is primarily that of Chabon’s maternal grandfather, referred to in the book always simply as “my grandfather.” The premise of the book is that on his deathbed, in 1989, his grandfather finally broke his lifelong habit of reticence and confided to Chabon the fantastic series of adventures that made up his life. These are the stories the novel retells, out of chronological order, and supplemented by Chabon’s own childhood memories, as well as facts ostensibly discovered through later research and interviews. But the book’s opening disclaimer makes clear that nothing we are about to read is to be taken as fact: “In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except where facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it.” And at the end, in his acknowledgments, Chabon confirms that many of the people and organizations referred to in the course of the book do not actually exist.

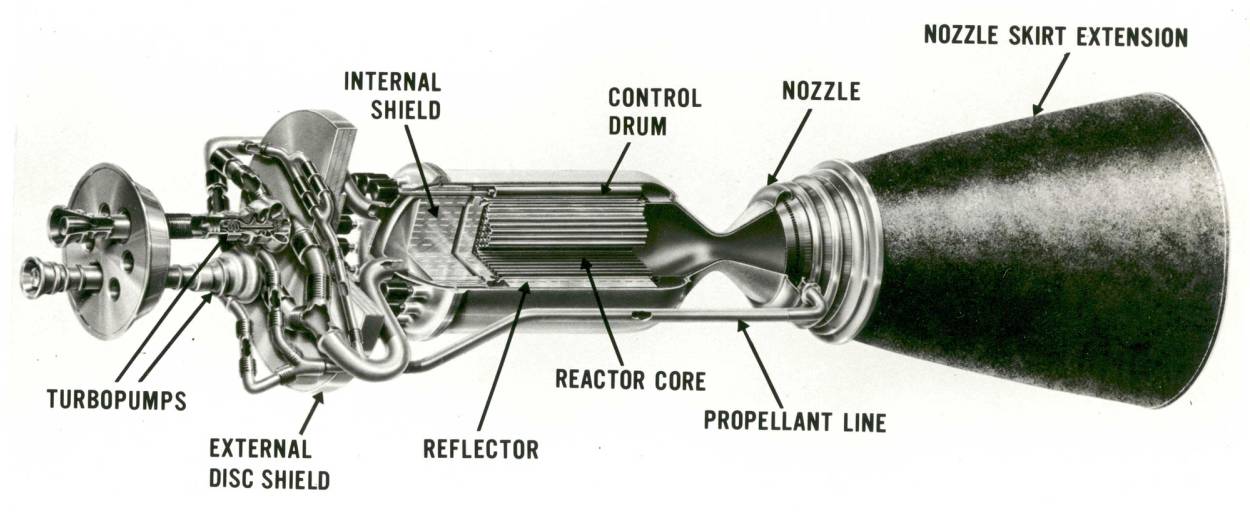

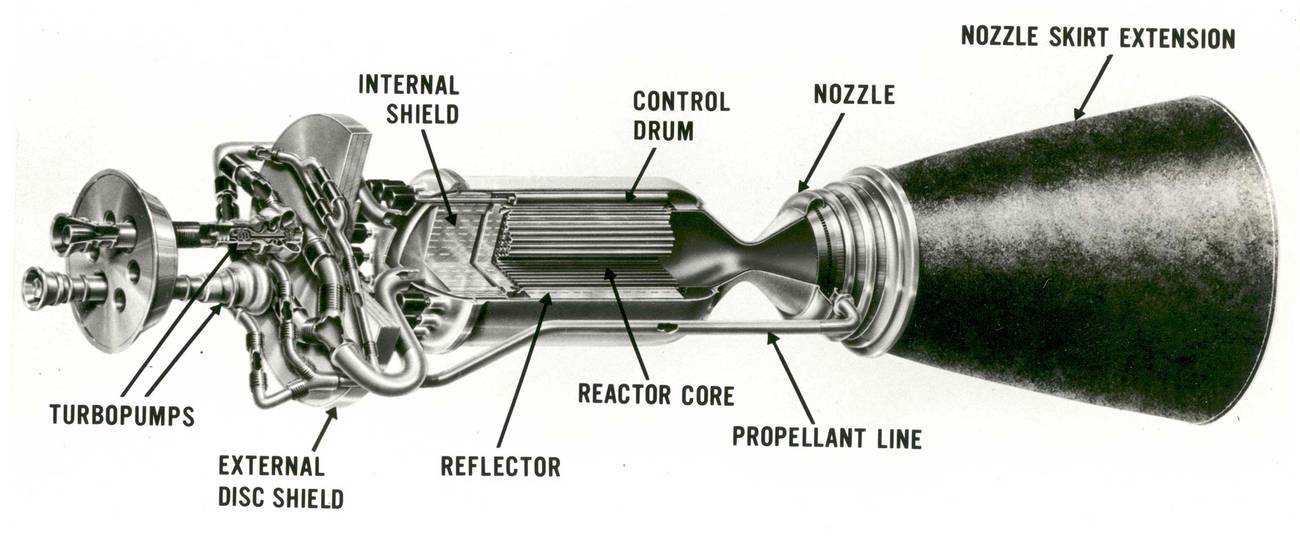

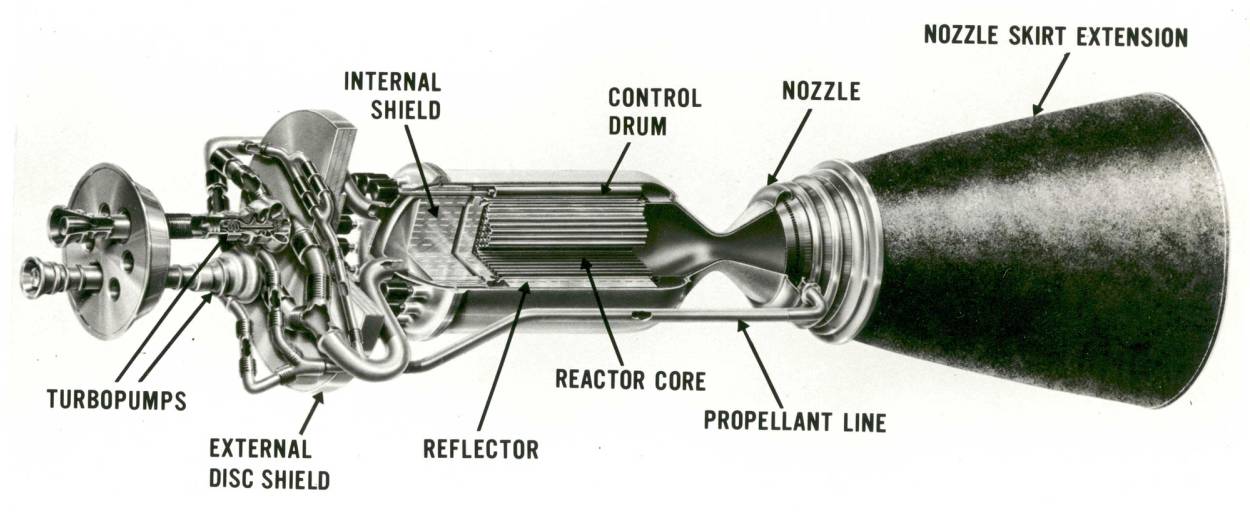

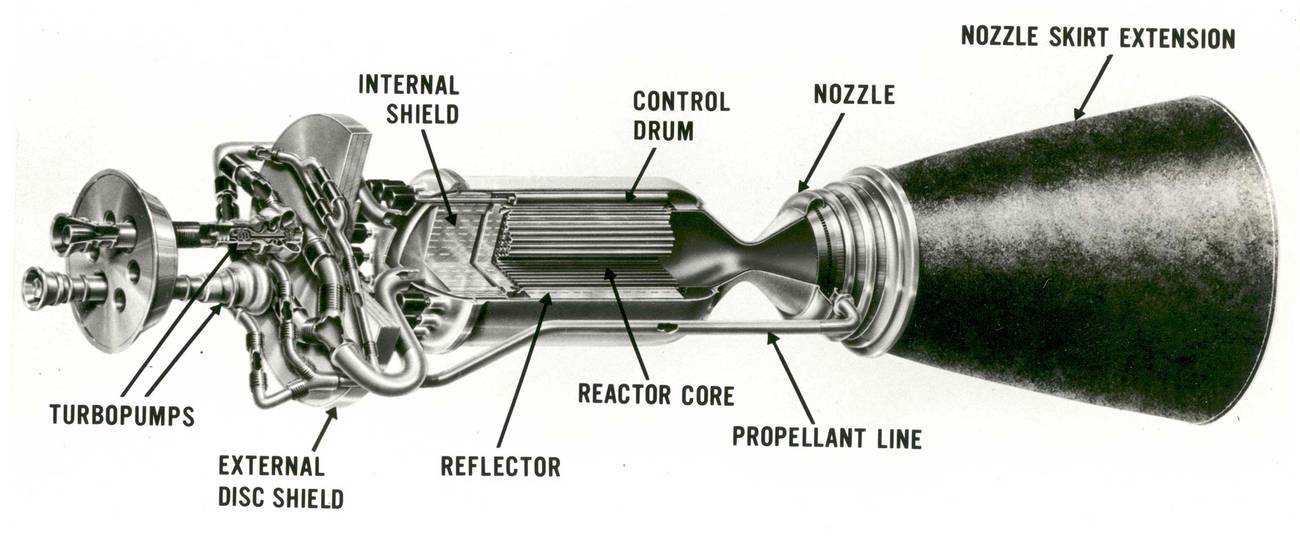

What we are reading, then, is a novel in the form of a memoir—a fantasia on biographical themes from the Greatest Generation. This becomes clear when you start to count the number of legendary people and events making an appearance in the grandfather’s story. On the first page, we learn that he was fired from a job as a salesman so that his place could be given to a disgraced and unemployable Alger Hiss, the accused Soviet spy. Later the grandfather is recruited for the OSS, the WWII-era precursor to the CIA, by the organization’s founder, Wild Bill Donovan. And his mission in the European theater—tracking down information about the Nazis’ rocket industry—gives him a lifelong obsession with Wernher von Braun, the German scientist who went on to become the father of the American space program. Toward the end of the book, the grandfather finally meets von Braun, under tragicomic circumstances.

These cameos by famous people give the book a picaresque quality, as if Chabon’s grandfather were on a ramble through the 20th century. But he is no Candide, because he never had any illusions to lose. The earliest episode Chabon recounts is of his grandfather as a teenager, meeting up with a tubercular runaway prostitute who lives in a railroad switching yard. This is his first sexual experience, and it is a grim, horrible one, the overture to a life which will expose him to the worst of history and humanity. Before his story is over, Chabon’s grandfather will have liberated a concentration camp, spent time in an American prison, and visited his wife in an insane asylum. Yet he will also have crucial experiences in the conventional precincts of American Jewry—he meets the two great loves of his life at a synagogue’s Monte Carlo night and in a retirement community in Florida. This blending of extremity with banality is part of what gives Moonglow its air of being a fable or romance. Yet as Chabon reminds us, that incongruity was a fact of life for much of the WWII generation—especially for the men who saw indescribable horrors on the battlefield, and then came home to start families and buy houses in the suburbs.

At the heart of this 20th-century Jewish story, inevitably, is the Holocaust; among other things, Moonglow is a book about the way this trauma is passed down to the second and third generations. Some of the most powerful and moving writing in the book comes when Moonglow puts the grandfather’s story on hold and adopts the perspective of the narrator himself as a child, trying to figure out the mysteries that his parents and grandparents are so dedicated to hiding from him. In one episode, the boy is terrified by the fancy French puppets his grandmother keeps in a box in the closet, and it doesn’t take a Freudian to understand that, through the dolls, he has intuited something about the Old World terrors she is hiding.

As the story unfolds, we learn that the man Chabon calls his grandfather is not actually biologically related to him at all. When he met Chabon’s grandmother, she had already borne the child who would become the novelist’s (or, safer to say, the narrator’s) mother. The grandmother, we learn, was a French Jew who became pregnant as a teenager and was sent off to a Carmelite convent, where she survived the German occupation in hiding. After the war, she made her way to Baltimore, where she cut an incongruously glamorous figure. She even had a career on local television as the host of a night-time horror program, in which she played a character called “the Night Witch.” It was at a Baltimore synagogue that she met the narrator’s grandfather and fell in love with him—though the ladies of the shul had intended for her to marry the rabbi, who was the grandfather’s brother.

For Chabon, having his grandmother play a witch on TV is just the kind of literal, exaggerated metaphor that he needs to convey her strange power. Indeed, she is just as witchlike in real life, entertaining her young grandson by telling tales based on a Tarot deck. These stories give the narrator his earliest sense of his grandmother’s uncanniness: “I liked the way my grandmother told a story, but the characters who emerged from her witch’s deck unsettled and frightened me, and the fates that befell them were dark.”

What he does not yet know, but what the reader will learn over the course of the novel, is that his grandmother is afflicted by a terrifying mental illness, which takes the form of hallucinations involving a sexualized figure she calls the Skinless Horse. Here again, Chabon makes the abstract highly literal—you can imagine the Skinless Horse as a comic-book supervillain—in effect trading psychological complexity for narrative power. Chabon builds the suspense surrounding the grandmother: Just how bad is her insanity going to get? What is its connection to her experiences as a young mother during WWII? Is she telling the whole truth about her past? Does anyone?

Moonglow provides its own answer to that question. We can’t grasp the past simply by knowing it accurately; the facts do not capture either the fullness of a life as it is lived or the mythic power it gains when it is recounted. Like the moon, we see the past from a great distance, through a transfiguring light. Yet the grandfather spent much of his career working on rocketry and dreaming of a moon landing; and as we know, in the end, humanity did get there. This novel is Chabon’s Apollo mission to the past, launched with the same combination of ingenuity, dedication, and wonder.

***

To read more of Adam Kirsch’s book reviews for Tablet magazine, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.