Biopolitics

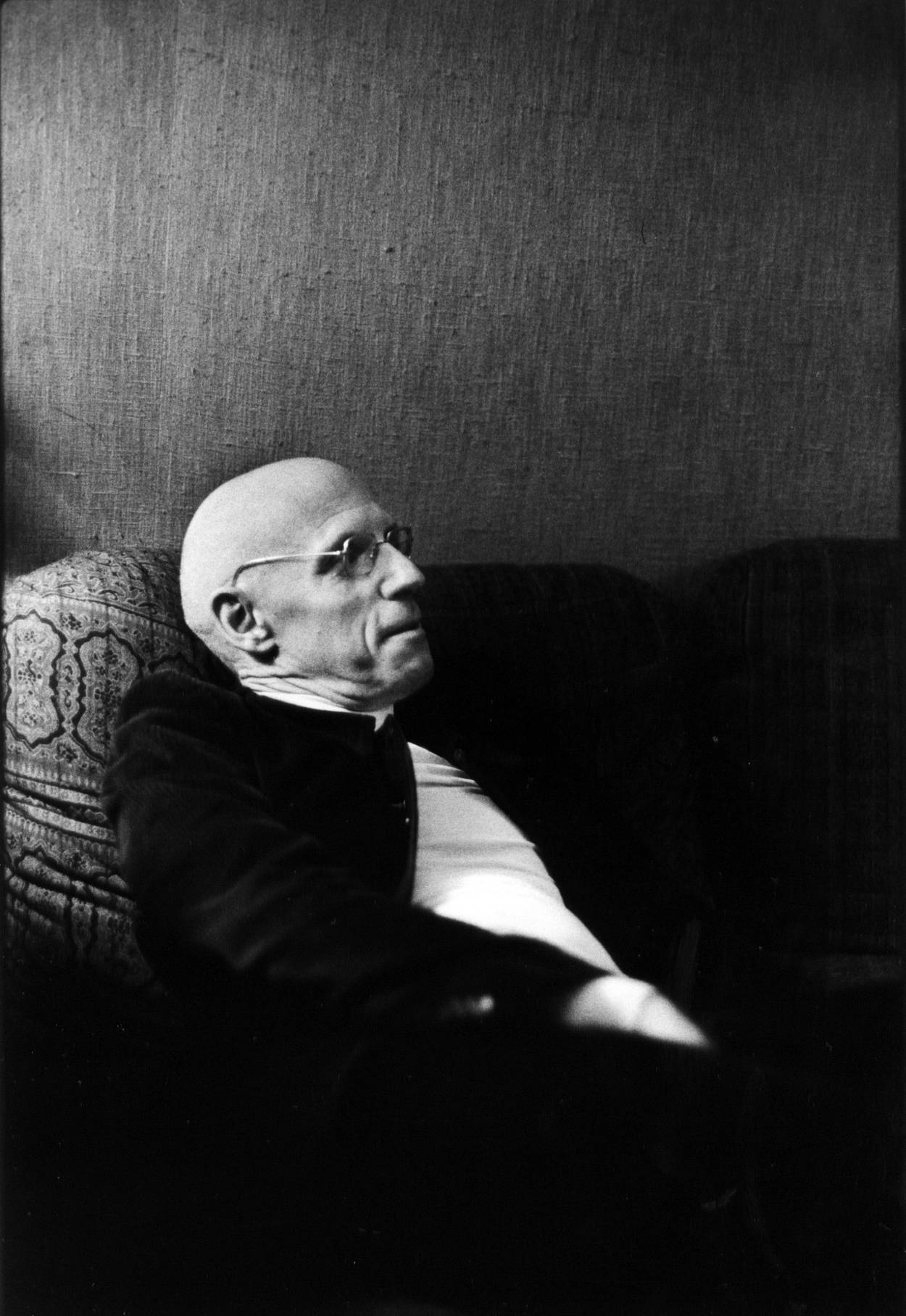

Michel Foucault understood that truly free people must be willing to choose death, like the fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. What would he make of the restrictions on liberty in our efforts to safeguard life from COVID-19?

The rights of citizens in a liberal democracy are worthless if they can be suspended at any moment, as the COVID-19 crisis reminds us. Phil Murphy, the governor of New Jersey, blithely admitted he “wasn’t thinking of the Bill of Rights” when he imposed social distancing guidelines that forbade collective religious observances. Guided by experts appealing to the authority of science, our political order reveals itself not as a regime of representatives beholden to electors and protecting their unalienable rights, but as a system of collective life support.

Many of us are apparently comfortable with such a system, and only wish its managers were doing a better job keeping us alive. To the French philosopher Michel Foucault, who died 36 years ago today, however, the problem is not that this system does not work, but that it indeed works so well we hardly miss being free citizens. Those of us who remember our rights—from Orthodox Jews holding religious services in New York and Israel to groups protesting lockdowns across the United States—appear to many of their compatriots as dangerous and reprehensible. They are fair game for the worst charges our contemporary society can imagine—to be accused, as Jamelle Bouie at The New York Times accuses them, of being agents of white supremacy. Respectable opinion apparently finds no terms too severe (or absurd) to express its abhorrence.

Over the course of the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault became convinced that human freedom was deeply imperiled by such alliances of opinion-makers, experts, and politicians. Against them, liberal democracy, with its guarantees to certain basic liberties and to participation in a process of collective self-determination, appears powerless.

Dismayed by the weakness of liberalism, and at the same time with the “totalitarian” implications of Marxism, Foucault experimented with other forms of radical leftist politics, which proved equally disappointing. He flirted with French Maoism in the early ’70s and later in the decade was a sympathetic observer of the Iranian Revolution. Knowing neither the Persian language nor anything in particular about the history and culture of Iran, Foucault perhaps ought to have thought twice about having an opinion on the movement against the shah that rocked the country in the fall of 1978. He was, at any rate, aware that it had coalesced around the demand for “Islamic government” and the figure of the Ayatollah Khomeini, then in exile in France.

In an interview with the Iranian philosopher Baqir Parham in September 1978, Foucault sketched a bleak portrait of modern Western history. Liberal democracy, “the vision of a non-alienated, clear, lucid, and balanced society,” had produced “the harshest, most savage, most selfish, most dishonest, oppressive society one could possibly imagine.” Liberalism’s critics from the left, however, had only managed to contrive authoritarian socialist regimes and rigid ideologies “that today are condemned and ought to be discarded.” Modern politics tended inevitably to human degradation and unfreedom—and neither liberalism nor leftism offered a means of thwarting this trajectory.

Despondent cynicism and culpable hope are neighbors, not opposites. Over the following months Foucault became convinced that the Iranian revolutionaries’ demand for Islamic government offered what liberalism could not. He hoped that by offering a substantive ethic rooted in a collective experience of the sacred, an Islamic political movement might be able to restrain the systems of domination and manipulation that comprise biopolitics. In October 1978 he assured readers of the French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, “nobody in Iran” wants “a political regime in which the clerics would have a role of supervision or control.”

By March 1979, “nobody” had seized power. Khomeini installed a legalist theocracy that brutally abrogated women’s rights and began bloody persecutions of homosexuals, ethnic minorities, and the left. Foucault had hoped political Islam would provide an alternative to the reign of experts who suspend freedom and exercise violence over populations, but found it was only more of the same.

By the beginning of the 1980s his thought seemed to take a new direction. Many on the left denounced—and continue to denounce—what seemed to be his accommodation to “neoliberalism.” But it might also be said that Foucault rediscovered the sources of the democratic liberal tradition, founded on a willingness to die rather than lose one’s rights.

In early 1979, Foucault wrote an essay marking his shift in thought. He rearticulated an insight key to the American and French Revolutions of the late 18th century—that the assertion of freedom requires the risk of death. He argued that indeed there is no politics and no history, no possibility of truly human existence at all, without such a willingness to choose death.

From this new perspective, which was framed by his concept of “biopower,” Foucault turned to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as a model of what it means to be a free person. His claims may seem paradoxical and perverse at our present moment, when we are being told that we must all do whatever is necessary to preserve life—and that personal choices that raise the risk of contracting COVID-19 are the products of Tea Party ignorance, and even tantamount to murder. But it is important to consider Foucault’s perspective, for it recalls that the freedoms we enjoy (when we do enjoy them) were often achieved not by safeguarding life but by choosing death.

In 1976, Foucault published his landmark History of Sexuality and delivered a series of lectures at the Collège de France titled “Society Must be Defended.” In these, he laid out the basis of a new concept of power in the modern world, which he called “biopower,” or power over life. Since the 18th century, he argued, the state and other institutions have taken on an increasingly important role in managing “life,” that is, public health and personal well-being. Citizens, in turn, look to the state, medical professionals, legal experts, and a host of authorities to exercise what he called “governmentality” over their physical, psychological and even sexual flourishing.

Governmentality and biopower extend far beyond the state. Our everyday lives are beholden to agents who interfere in our affairs in order to evaluate, predict, and transform our behavior so that we can keep ourselves and others safe. Consider the medical experts who call on us to be vaccinated or suspend our religious gatherings; the social workers who assess if we are fit parents or acceptable for parole; the university Title IX arbiters who decide if we and our sexual partners were consenting actively; the human resource officers who warn us about ideas and attitudes “unsafe” for the workplace. We have become a herd that expects to be cared for by benevolent and well-informed shepherds.

Agents of governmentality appeal to their superior knowledge and their interest in our well-being to moot any appeals to the freedoms our liberal regime is supposed to protect. Gov. Gavin Newsom declared that he will listen “to science” (that is, to scientific experts) “not politics” (that is, to voters and their representatives) in determining when and how to reopen California. Citizens’ rights appear irrelevant in the face of demands that we cede to the epistemic authority of science and accept whatever is being done for our safety. If basic rights are, in principle, suspended only in a state of emergency, then modern governmentality is a continuous state of emergency in which one’s freedom to speak, worship, etc. can always be cast as endangering the public and ignoring scientific knowledge.

A politics centered on life, promising safety and well-being to a populace that must forgo its rights, can become a murderous totalitarianism, Foucault argued in the conclusion to both “Society Must be Defended” and History of Sexuality. Both the Soviet Union and the Nazi regime were examples of biopolitics, in which the state, allied with medical, psychiatric, and other kinds of experts, promoted “life” and vitality. The Soviets tried to bring life to a new “Soviet man,” “regenerating one’s own race” through purges. Summarizing the logic of the Soviet state, he quipped, “as more and more of our number die, the race to which we belong becomes purer and purer.”

The Nazis, too, conducted purges of what they called the “lifestream,” murdering those who seemed to threaten its purity. Their discourse of “living space” and “cleansing,” Foucault insisted, was not simply metaphorical. They were taking, to a genocidal extreme, the notion, implicit in all modern politics, that “the essential function of society or the State, or whatever it is that must replace the State, is to take control of life, to manage it.”

The Holocaust, Foucault argued in the conclusion of History of Sexuality, will be misunderstood if we see it as the antithesis of our own politics of public health and welfare, focused on preserving life. Genocide is in fact their extreme endpoint, because in them “power is situated and exercised at the level of life” and “at stake is the biological existence of an entire population.” Power wielded for the sake of human flourishing often requires suspending rights in the name of its own imperatives in order to do its job, producing the horrors of the gulags and death camps.

If one is interested in human freedom and dignity, then the inability of liberal formulas to restrain the encroach of governmentality is a dire problem. One solution might be to attempt to denounce all manifestations of the latter as wicked conspiracies against liberty. This seems to be what the Italian thinker Giorgio Agamben has adopted in the face of COVID-19, which he describes in conspiratorial tones as an alibi for the state and medical institutions to extend their control over our lives. The current crisis is thus nothing but a viral equivalent of the Reichstag fire.

Agamben’s comments have been rather poorly received in the Anglophone world. The writer Anastasia Berg chides him and postmodern “theory” generally for failing to understand the urgent threat to life at stake in the crisis. If not here, at least on the left one might have expected to find some sympathy for Agamben’s views. For many years academic and journalistic opinion has articulated quite similar ideas on the subjects of Islamic terrorism and the refugee crisis. Many argued the latter were not real dangers, but mere excuses for right-wing politicians to stir up anxiety and justify the extension of state power. Yet when it comes to disease, it appears that the value of human life—or fear—is understood to trump all other values.

Preserving freedom would be easier, certainly, if the dangers that biopolitics claimed to manage were imaginary. But Foucault, not being a fool, made no such argument. In one of his earliest studies of the problematic relationship between liberal democracy and public health, The Birth of the Clinic (1963), he observed that during the French Revolution liberals had attempted to abolish the (quite recent) system of medical faculties, hospitals, and bureaucrats that governed French public health. This system violated citizens’ rights to adopt whatever medical practices they pleased and made them dependent on the state—obvious departures from liberal ideals. But revolutionary reforms of France’s nascent politics of life caused a medical catastrophe, as disease and quack doctors circulated across the country, and the authority of medical experts was swiftly restored regardless of its violations of revolutionary principles. If biopolitics were merely a sinister ruse of power, it could be exposed and undone, but it appears, Foucault warned, that we cannot imagine our lives without its promise of protection.

As the new Islamic Republic revealed itself to be at least as oppressive as the regime it replaced, Foucault faced widespread condemnation in French media for having supported it so prominently. For several weeks he resisted demands to apologize, but in early May he acceded, publishing an essay in Le Monde, France’s most important daily newspaper. This text, “Is It Useless to Revolt?” is far more than a response to a momentary embarrassment. It represents a point of departure, a turning away from the fashionable radicalisms of the ’70s toward a new humanism.

The essay begins by juxtaposing two slogans. The Iranian revolutionaries had said in the fall of 1978, “we are prepared to die by the thousands,” sacrificing their lives to topple the shah. By the following spring the ayatollah was demanding—in an echo of the Soviets as Foucault paraphrased them in his lectures on biopower—“may Iran bleed, so the revolution will be strong.” The revolutionaries’ willingness to die for their freedom had been transformed into the Khomeinist imperative that the people die for his power.

Revolt had failed in Iran. The “terrors of the Savak,” the shah’s secret police, were replaced with “amputated hands,” the barbarities of Sharia. Whether it should have been obvious from the beginning that this would be so was not something Foucault wanted to discuss. Turning the tables on his critics, he argued that these are just the kinds of questions no one can ask “a single man, group, minority or whole people” who have risen in “revolt.”

To revolt means to “risk one’s life against power,” to accept the possibility, or even the inevitability, of death rather than continue obeying a regime or rule. Those who revolt cannot be governed, because they no longer fear death. Nor can they be swayed by any observer who would tell them, “it is useless to revolt, things will never change.” How can one for whom death has no terror fear being charged with folly and futility?

The question is not whether such and such people should revolt or should have revolted—they do not listen to such questions. What we ought to ask instead, Foucault insisted, is what it means for us that “people do in fact revolt,” that we are beings that can choose death rather than life, apparent madness rather than reason. There is an “enigma of revolt” that goes to the heart of what it means to be human.

Foucault had previously eschewed such claims about human nature. In his 1971 debate with Noam Chomsky, he declared that the desire to make statements about the kind of beings we are is a trap. But considering revolt forced Foucault to change his mind. Our ability to choose death, he realized, is a kind of counterpower that “threatens every despotism, those of yesterday and today alike.” The “power one man exercises over another is always in jeopardy,” because each of us possesses, inalienably, a power over ourselves.

Our ability to revolt by risking death seems bound to fail, unable to liberate us individually or bring about an enduring order of freedom. But it is also an ever-present, ever-possible means of thwarting projects of domination. Foucault had argued in “Society Must Be Defended” and History of Sexuality that the Third Reich represented the danger of biopolitics, which has an inherent trajectory to suspending rights and causing deaths in order to preserve and promote life for those deemed worthy to live. Now, as if to balance the paradox that the politics of life ends with mass death, he observed that our potential for revolt finds its clearest political expression in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

No domination can ever be so total as to eliminate our “irreducible” capacity for resistance: “Warsaw will always have its ghetto in revolt.” This may not seem an encouraging example. If the Iranian revolutionaries had failed by bringing about another oppressive regime, the men and women who rose up in the spring of 1943 against the Nazi occupation of Warsaw knew from the start that their fight could not end in victory. But, Foucault suggests, what is important is precisely that the uprising in a sense never ended and never can end, because it discloses an essential dimension of human agency, showing us what we can do when we refuse fear and obedience.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s French intellectuals, Foucault among them, had followed revolutions throughout the Third World with hope, looking successively to Cuba, Algeria, North Vietnam, and Iran for a new model of political transformation. Now, however, he was suggesting that such a search had been wrong from the start. Just as ultimate evil at the heart of modern politics—genocide—is virtually present in every suspension of human rights in name of life, so too is the ultimate expression of human freedom—the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising—always ongoing, always still “in revolt.”

Few perhaps will see the crowds protesting COVID-19 lockdowns as acting in the same spirit as those who brought down the shah or rose up in the Warsaw ghetto. It is certainly more convenient to dismiss the former as fools or racists. But revolt, Foucault knew, is not necessarily something to be desired or admired. There is revolt whenever a criminal resists arrest, whenever a madman escapes from an asylum—as Foucault noted, revolt “neither proves the one innocent, nor makes the other sane.” Revolt will always appear criminal and insane to those in whose interests our categories of legality and sanity have been defined.

“No one is obligated to be in solidarity with them,” Foucault said of those who risk their lives to revolt. But, he urged us to remember, it is only their willingness to risk death that “provides an unconditional limit” to the ways in which biopolitics inevitably suspends and usurps our freedoms. Confronting the multiple forms of power that suspend our rights in the name of science and life, Foucault warned that “no rules are ever rigorous enough to limit it ... universal principles are never strict enough.” Neither the formal, codified rights enshrined in constitutions nor moral slogans about the importance of freedom will ever prove adequate, because the power to protect life is potentially “infinite”—as limitless as the potential risks to the lives it claims to protect.

The rights we enjoy—to the extent we still have them, to the extent we still want them—were won by people taking such risks. “Every form of freedom that has been acquired or is being demanded, all the rights that we insist on, even the ones that seem to be about the least important things,” Foucault wrote, are rooted in the possibility that at any moment we might choose to risk our lives rather than obey orders. Liberal democracy works, so far as it does work, not because its legal mechanisms or official values have any virtue in themselves to protect us from power, but because they can incite us to remember the irreducible element of freedom—the freedom to choose death over obedience.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.