Minor Threats

The punk icon Ian MacKaye always wanted to create a tribe. Now an elder statesman of D.C. hardcore, the musician talks about organized religion, breaking toilets, and making peace with his mother’s death.

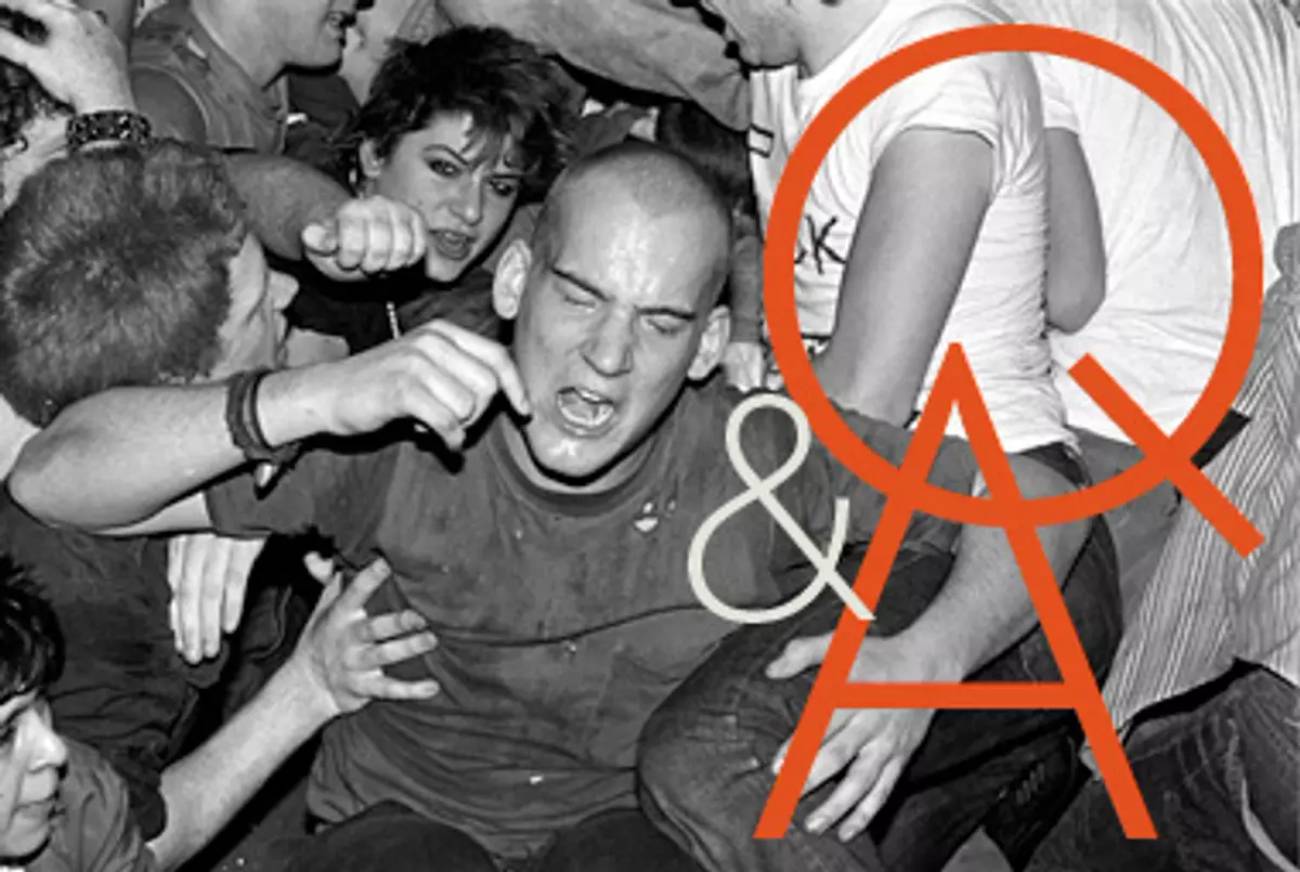

With his shaved head, bare chest, and the lurching, incantatory presence of an escaped mental patient gone defiantly off his meds, the punk rock singer Ian MacKaye made it impossible to look away from the moment he appeared on stage. The simple chords and direct lyrics of the songs that he wrote and sang for Minor Threat, the hardcore punk band he formed in 1980, plunged his audiences into a sea of roiling emotions while assuring them that they were not alone. Along with his friend Henry Rollins of Black Flag, MacKaye furiously rejected the stale and bloated sounds, emotional passivity, and the self-destructive ethos of 1970s rock ‘n’ roll in favor of the communal experience of music in which opposing poles of emotion were brought together in a chaotic, frenzied experience of something that sounded and felt entirely new—angry and caring, simple and emotionally complex.

Setting off small rooms of sweaty teenagers in Washington, New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and other cities that would tolerate punk and the increasing violence of the scene, MacKaye was part angry adolescent and part caring older brother. He used songs like “Good Guys (don’t wear white),” “No Reason,” and “Filler” to teach his followers to feel and express their emotions directly, to make art and meaning out of whatever materials were at hand. Railing against smoking, drinking, doing drugs, and other corporate-promoted self-destructive behaviors, MacKaye set himself apart from decadent punk progenitors like the Sex Pistols and created the musical sub-genre known as straight-edge punk. After Minor Threat disbanded in 1983, MacKaye formed the legendary 1990s indie rock band Fugazi, which blended poppy hooks with MacKaye’s emotional directness and a DIY ethos on hits like “Waiting Room” and “Song #1.”

MacKaye’s heightened awareness of the importance of music and ritual as expressions of the values that shape communities and hold them together are products of both the D.C. punk scene and of growing up in a family highly engaged with organized religion: MacKaye went to church every Sunday, and his father was the religion editor of the Washington Post. I attended one of the final Minor Threat shows, in Philadelphia in the summer of 1983, as a 16-year-old yeshiva student, and it rewired my brain in ways that continue to deeply affect my life. A few months ago, I went to Washington to meet MacKaye—who is now the father of a young son and the head of his own record label, Dischord—and talk about the energy I’d felt in that room when I was 16, where it came from, and what it meant to me and thousands of other adolescents yearning at once to escape and be on their own and to be told that they were OK. We spent an afternoon talking, drinking tea, eating whole-wheat toast with honey, and talking about music and other things that matter. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

Do you remember playing a Minor Threat show in Philadelphia in the summer of 1983?

Where the kids were jumping off the sides? We were fucking good that night. That little run of shows, I just felt like we had hit our stride, we were back to the four piece, we were so lean and so fast, and everything just felt so right. We broke up two months after that. We played our last show on September 24, 1983.

I grew up in the Orthodox Jewish community in New York, and I went down to Philly for that show, and it blew my mind.

Were you actually a practicing Orthodox Jew at that time?

I grew up in that community. Minor Threat was my favorite thing that I had ever seen. Seeing people my age fired up with that communal energy, which was weirdly a lot like the energy that I’d felt from religious people, except you didn’t seem to like religion very much, as far as I could tell from songs like “Filler.” You felt like everyone’s big brother, but you were also really pissed off.

I understand that a lot of the time I looked like I was enraged—I wasn’t really enraged. I might have been pissed about things in a song like “Filler,” in the sense of this is wrong, but what I really was doing was I was taking advantage of the speed of the music and the energy of the room to completely express, to go off, to make it real, to make it visceral.

You wanted to ignite the room.

You may have looked at me like an older brother, but I looked at everyone in the crowd like, “This is us.” We were all peers. The band wasn’t putting on the show, we were all putting on the show.

Straight up, I think music is sacred. I think music is a form of communication that predates language. Music predates religion, it predates business, it predates all of that stuff. It’s serious. It’s not a fucking joke. I’m not a Christian, I’m not a Jew, I’m not a damn anything. I’m not a team member. I understand why people are drawn to that, I respect it, even. But for me there’s something that’s even deeper, more sacred than all that, which is human beings figuring out how to gather. Music can set us free in that moment. And if we’re in a room with other people who are all being affected this way, then you get into that mass energy, this thing that can be really cathartic. And I think it is a really deeply important thing to have happen, catharsis. To go off.

The problem is, because people are drawn to it, because it’s so fucking important, people always say, “How can I set up a tollbooth there?” How can I get them to come to my place, so I can charge them and make money from their rite, their ritual.

When I was a kid, my family were Orthodox Jews, although my parents were complex because they didn’t believe in any of that stuff in a literal way, they just brought us up in that community, in that culture. And so, at one point when I was a kid—maybe 10, 11, I guess it was—things weren’t so good in my home, and there was this real deep Hasidic community in Brooklyn, black hats. And so this one rabbi in my school was like, if you want to go away for the weekend, we can find families and you can spend the Sabbath with them, and I did.

But the weekends were bad, because you were in school during the week, but the weekend was like the warzone.

Yeah, and these people were religious people, so you’d get some spirit or something from them, which sounds bad but it was actually great, and I loved them. They were just in their own world. They’d all eat together with their rabbi, and then at the end someone would start singing these songs and wordless melodies they’d carried with them from Russia, and they would then sing for five or six hours. And it would just be men in this room, singing, and you would feel that intense energy. The next time I felt that again was at your show. But it was different, you know.

My songs are made to be sung by many voices. All I ever want to do is make the whole room sing. Because I knew if everyone’s singing, they’re making a show, they’re part of the music. And it makes for something really phenomenal. I always tell people let’s all sing, sing the songs, let’s make music, fuck buying music, stop downloading it, make it. Be the song. Be the song.

But how do you keep that ritual part of it fresh? That’s the thing I always wondered. Your song with Fugazi, “Waiting Room,” is one of the best songs ever. Lyrically, musically, I never get tired of it. To the extent that there was one Fugazi hit, it was the hit.

That’s my hit song.

So, you played it what, a thousand times?

But what’s not repetitious about it is that every moment is not the last moment, and you never know. Like if you’re having sex with someone, maybe it gets repetitious, but it doesn’t feel that way to me. It’s a song. Every time I played “Waiting Room,” there’s potential for that moment. That song hits people, they love it, it’s important to them.

Just as you were talking I was thinking to myself, there are all these Fugazi songs like “Song #1” or “Bad Mouth” where you could do such delicate, girly versions of them. They would be exquisite.

Yeah, like pop songs. They’re singalongs.

A song is a thing that other people can sing along with you?

I’m going to go pee and think about that one.

[Leaves and returns.]

It’s funny, for me, songs are kind of indefinable shapes. And this might be the difference between music and songs. Records are sonic illusions. We have this little boombox with the speakers that are like two inches big. You have these recordings you put it on, you play these things, and it creates a scenario in which I’m at a concert. But you’re obviously not.

I think of artists and other people, they’re translators. Visual artists see things, and they say, I’m going to translate this, and they take a picture or they paint or they draw. You compose things and you frame it for people, because the way they process they don’t see it the same way. They can see it, but they can’t catch what you’re seeing.

Musicians, I think we hear things in a certain way. I’ve taken out all this noise and I’ve given you this distilled version.

I’m always looking for some little model world or some metaphoric universe that I can use to rewire people’s brains a little bit so they can see and feel in the way that I find good or natural.

I was being attacked on stage. If you rocked out at all you must have experienced the car going by with the guys jumping out, to rewire people’s brains that way.

There were more than a few kids from D.C. who came to New York shows and were ill-mannered. D.C. boys had a reputation for that shit.

Yeah. We did. I have no regrets. In the very beginning, we were not looking to fight. We wanted to create a tribe. We wanted to have an extended family. Because I think that all of us were marginalized for one reason or another. Most people had bad family experiences. Some people were gay, or white in a black city, or black in a white scene, or they were just weird. All the deviants gathered and I thought, I’m a deviant. Being straight—not taking drugs or getting high or drinking—in those years, that was really deviant.

And your first idea is, OK, we need to protect the tribe.

I had identified as a pacifist my whole life. But that time I thought, all right, I would bruise the ego, not the body. Violence is always wrong, but sometimes it’s necessary. It’s never OK for me, but sometimes it’s necessary. When the skinhead thing really started to flourish, I felt, oh this is so depressing. I remember saying to these skinhead kids, “What are you doing? Have you lost your minds?” And they were like, “You started it.”

Something that’s been so present in you, and in your music from the first moment I encountered it, is a powerful ethic of responsibility. It wasn’t control freak-y, but it sounded like you gave a shit about stuff.

Because I gave a shit about stuff.

That’s not what you think of with rock musicians.

That’s why I’m a punk. [Laughs.] I remember some of the random violence we were talking about before. It’s one of the weirdest things about punks, or anybody. Why destroy a toilet? If ever you’ve been to shows in Eastern Europe it’s like, what are you people thinking? You’re breaking all the toilets, we need the toilet to take the shit away. It is our friend. There’s something that’s perverse about people that they have to break toilets. A toilet is such a good thing to have around.

When you have a community that doesn’t have an established hierarchy, like punk, or Jews, or whomever, the bad part is then some asshole stands up and says, follow me and do what I do, I’m the leader of the community. My name is the Lorax, I speak for the trees.

The reason the person who broke the bathroom was so frowned upon was because that person’s decision is putting the venue in jeopardy. So, if some guy who we’ve never met before shows up and breaks up a bathroom, he just did damage to our world.

You must have had over the years many hundreds of people going, “Oh, fucking punk rock, look at you, don’t steal, don’t drink—you’ve torn all the wires out of your head so you could become the ultimate bullshit conformist artist.”

The problem with the Ten Commandments is that’s when the Christians got hold of the obviousness and said like, “This is our grid, check it out.” It’d be like saying eating bread is a Christian thing. Bread predates fucking Jesus. So, the Christians superimposed their concept on what is already there. So, it seemed obvious to me that the really deep ideas are always going to occur with a smaller number of people. Because it’s not performance at that point.

So, now tell me about your dad. He’s a religion editor at the Washington Post. He was a theologian. How did that figure in your home life and in the ever-evolving ethos of straight-edge punk?

My mother was Catholic, my father was Episcopalian. Both my parents got involved with religion on their own, through their own volition to become practitioners. We went to this church, St. Stephen and the Incarnation, on Newton Street, northwest D.C. It was a very poor, very crime-ridden area. It was an inner-city church. It was a white church in what had become a black neighborhood in the ’50s, through block busting. It was a very radical church. In fact, we were part of a gay marriage in 1972. Black Panthers had a headquarters across Newton Street so they were regularly coming through. We had rock bands play there. They pulled the pews out of the front and we sat on cushions on the floor. You didn’t have to dress up, we just wore whatever we wore. We were hippie kids kind of, raggedy kids. I got beat up by kids, these tough kids who were there. There were a lot of homeless guys around.

Did it feel dangerous and scary?

Yeah, because it was dangerous and scary. That neighborhood was really dicey. I told you it was 16th and Newton. Well, there’s no 15th Street there, and 14th Street was where the [1968] riots were. I think two weeks after King was assassinated, Palm Sunday was the 15th, I think, the church decided to do the service on 14th street. So, we marched down to 14th street and all the way down smoldering buildings and National Guard everywhere and police everywhere. And we did a service in front of a house. And the front porch was the altar. And there was a woman named Mother Scott who was a folk-blues singer, and she was a fixture at the church. She was an old woman in her 60s, 70s maybe. But she played, and that moment for me was really intense. She was a blues player, and she played this music and I remember just thinking, “This is beyond, this is it. This is the real deal.” Because, with all the chaos, we could feel a connection within all this madness.

As I grew older in that church, I identified, like, “Yeah, I believe in Jesus, whatever,” but I remember this conversation I had with my sister Katie, who was my older sister, and her boyfriend. We were out on the front porch and we were looking at the stars, and I said, “How many stars are there?” and they were like, “Nobody knows.” In my mind at that time, I thought there had to be a finite number of stars. Because, at some point, heaven begins.

I was 10 or 11, and it just hit me. Like the, “Oh, my God, wait a minute, there’s no heaven.” I ran into the house, and I called my dad, who’s like the religious guy, I called him at the Post, his number was 223 something something. And I said, “Dad, dad, if there’s no heaven, there’s no heaven.” And I was like, “What happens when you die? What happens?” And he’s like, “Nobody really knows. That’s what people go to church for.”

And at that moment I was like, OK, I think I’m done with religion. I got my answer. It was a very heavy moment for me.

And then you created your own community.

It’s an informal collective. I’m not the boss of their lives, it’s just when it comes to this specific enterprise. First off, they’re getting paid to work and they get health care and all that kind of crap. But they want to make a record. But what they don’t want to do, for instance, is have to contend with maybe a really irritating guy who’s calling them, like an old band member who’s bugging them. So, they’re like, “Will you call and do this? I’m sick of it.” And what they don’t want to do is what I do. That’s my job.

So, after the religion beat, my father became the associate editor of the Washington Post. And then the late ’60s, early ’70s, you may remember everyone going fucking insane. Well my parents went insane too. There was total chaos in our family. There was a lot of drinking going on, a lot of some pretty crazy shit going on. Like scary, crazy, screaming, yelling, throwing things. They were upset, they were mad. I had decided very early, 14 or 15 years old, that I understood why the things that happened with my family were so upsetting, and why they’d be angry.

But I thought that almost surely that my parents would die before me, and I just had this sense that people are angry with their parents for many, many years and maybe they make up but sometimes they don’t. And after they die they’re like, “Oh, I regret ‘never.’ ” I thought, I’ll just forgive my parents now. So, I just forgive them, in the midst of it all. I just wanted to spend as much time with them while they’re here, because they’re going to die. I was like, “All right, I forgive you now. I just forgive you right now. You’re just fucked up people, like the rest of us.”

I think that if we see our parents in a way that we should, that they are holy beings. Your parents created you. You couldn’t exist without them. They are the creators. So, when you’re looking at your mom and dad, and you see them, sometimes they turn their head a little bit and see a human being and get freaked out.

It’s hard to be peaceful but not shut down in the middle of so much violence, whether it’s emotional violence or real violence.

When the planes crashed in 2001, I was here, and people were calling me and saying something just crashed in the World Trade Center. And we had a TV in that front room, and I went and turned the TV on and I saw, like, “Oh, whoa.” Because that’s sort of one of those nightmares. But then the other plane crashed and I was like, “Oh, I get it; it’s not an accident.” And I thought wow, and I turned the TV off. I just turned it off. Because I knew, for the foreseeable future, they’re going to show that over and over and over. And the only reason to watch it over and over and over is to try to make sense of what just occurred. What occurred was incomprehensible. It was pure brutality, that’s what it was. It’s an aspect of human beings that has been going on since the dawn of time.

I was looking at this tree right there, through the window. I could see it, and it was a beautiful day, it was just moving gently. And I thought that tree has been there for God knows how long. And that tree has been around for all these wars. And the birds, they’re flying around, they don’t give a fuck about these planes. It doesn’t mean anything to them. And I said, “That’s where I’m at.” Not that I don’t care. I do care. I don’t want anyone to die. But this idea of brutality, that’s a part of the human animal I just don’t connect to. That’s where I’m more at one with the vegetation.

I remember that day. I was in Brooklyn, where I live now, where I grew up. I crossed the street and I could see some smoke, but I figured it was from a factory or something, I didn’t know what it was. And I went in to get a cup of coffee at the deli, and there was a TV on, they said “a small plane,” and I was like “that’s too bad, that’s weird.” My brother worked near there, so I was worried. And then I came back, and I turned on the TV. And then I saw the second one, and I also turned it off. I was like I don’t want to watch this. But my girlfriend at the time, whom I later married, was like, “Well, we should go see what’s happening,” and I was like, “OK,” more because I didn’t want her to walk out on the street by herself. We walked down to the Promenade, which overlooks the river, and then the wind changed and this heavy black smoke started really blowing toward us. And I said, “We got to get out of here,” and she said, “What is that?” And I said, “It’s people.”

Word. That’s heavy. That’s people. That’s deep on so many levels. That’s just fucked up. [Laughs.] It’s not a joke.

Let’s please try not to breathe them in.

My mom died in 2004. And around that time when she died I really started thinking. And then at some point I thought, I just have to stop thinking about this. I’m not going to get anywhere with it. Make peace with the fact that it’s incomprehensible.

I love my kids. I like to read books. I like to write. There’s some specific music I like to listen to. But in general, I don’t experience myself as so separate from other people. I think there’s a certain kind of energy that I have in a moment, and then I’ll get some energy from someone else. I know I’ve got some energy that’s fucked up and I’ll try not to inflict it on someone else, but then kind of I do and I feel bad about it. So, there’s all this energy going through the world and through people who are all connected to each other in all these circuits, and you can’t begin to imagine where they begin and end and how they came to be. We are just so many pathways that energy goes through. So, if I die, what’s missing, you know? Of course there are specific people that I’m responsible for, and then I worry about what happens to them, but I worry about that everyday anyway. It’s not like that’s some special concern reserved for after I die.

Have you not been around people who are facing mortality? I actually think a lot of people, not all people, they go insane. People go crazy because suddenly they’re like, life is like, oh my God.

I remember my grandmother when she was 92 years old. She lived in Montreal, and she was kind of an insane freak, but in that moment she was just very open. And she said, “All my friends are dead. My husband is dead. The only reason I’m alive right now is because your mother wants me to be alive, and she can’t deal with the fact that I want to die.” And I was like, “Oh, you’re healthy enough, you’re in a wheelchair, you listen to the radio, you read your books.” And she was like, “Whatever. I did all the things I wanted to do in my life. Now I’m in this pain, and this and that.” And then she was like, “Look, the only thing that matters is: Make sure you find someone you really love and who loves you. Make sure you love other people. Nothing else matters. And if you can get your mother to stop bothering me about the doctors and whatever then I can die faster.” And I was like, OK. I kind of walked away and was like, “She’s not supposed to say any of that but she did.”

But in that example, your mother is the crazy person.

Yeah.

I don’t know your mother.

She’s a doctor. They’re afraid to die.

When my mom died, she and I talked a lot about her death. She had emphysema, it was like six years. She was going to die, and it was very clear, and we knew it. And we talked about it the whole time. One evening, when my brother was reading to her, she grabbed the book cover and ripped it off. And took a pen and in her shaking hand wrote, “casual cruelty, horrible food equals the hospital, get me out of here.” So, we were like, we have to get her the fuck out of this place. So, we got her out of the hospital, we got her back home, and we just said, “OK, now you’re dying.”

I was thinking, like, what if you’re a parent dying. And the last thing you hear from your children is like, “Don’t go, don’t go,” and I thought, “That’s not going to help.” So, I said to my mom, “Go. You’re good. Everything is fine.” She said to me at one point in the hospital, “It’s not bad, it’s just different.” So, every time we get in the cycle of dying, I’d say, “It’s not bad, it’s just different. You can do this. You’re safe, you’re supported, go. We’re going to take care of each other, everything is good.”

That’s what a person would want to know.

It was really profound, because that moment at her death—which was something that as a child was my greatest fear in the world; I spent years saying I can’t bear to think about my mother dying—only to find out, in that particular circumstance, it was probably one of the most beautiful, profound moments of my life. It was a deeply beautiful moment when she died. Unbelievable. If only because she had been on a breathing machine for fucking six years and her last breaths we turned the machine off. And after a while you don’t recognize the sound anymore. We turned it off, and it was 5 a.m., it was a beautiful morning, it was June 30, 2004, and the sun was coming up. It was perfect silence for the first time in six years. Her last breaths. We could hear birds, it was a really incredible experience. And then, it’s a lot to go into, but we actually had a friend build a coffin for us. And we had it waiting in the garage. We had the wake in our house. No doctor or professional person ever came. We had a doctor who was on vacation so he just mailed us the death certificate.

Now, I’m reticent sometimes to talk about this, because a lot of people their experience with the death of their parents is not positive at all. I don’t like to talk about it and be like, “Oh, it was so great.”

It was great because of what you brought to it.

Well, that’s what I like to think. But that suggests other people don’t bring that.

People are generally pretty freaked out.

And that’s why I do think about what happens when you die. Because I think that people, if they could make peace with incomprehensibility, then I think we would live better in this world.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.