My Favorite Anti-Semite: An American Jewish Reflection on Ty Cobb for Opening Day

He was the greatest and strangest of all ball players, a fierce competitor, and a hateful person

I used to memorize baseball statistics from a big book called The Baseball Encyclopedia. It wasn’t that I was a kid with an affinity for math; I loved just the odd specificity of them. In the Baseball Encyclopedia, the highest number in a given category in a given year was printed in bold—the career records of the best players were dotted with bold totals. For the very best players, like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, the typographic representation of their greatness jumped off the page.

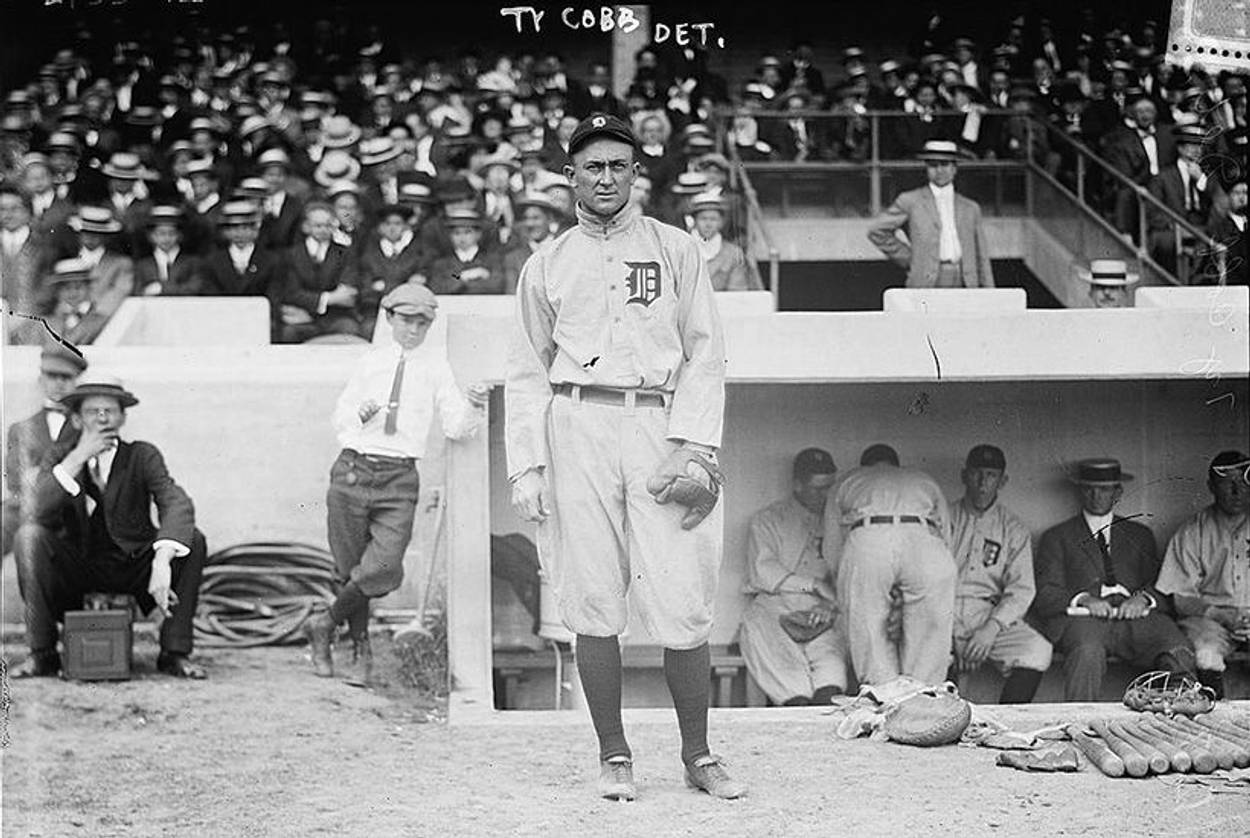

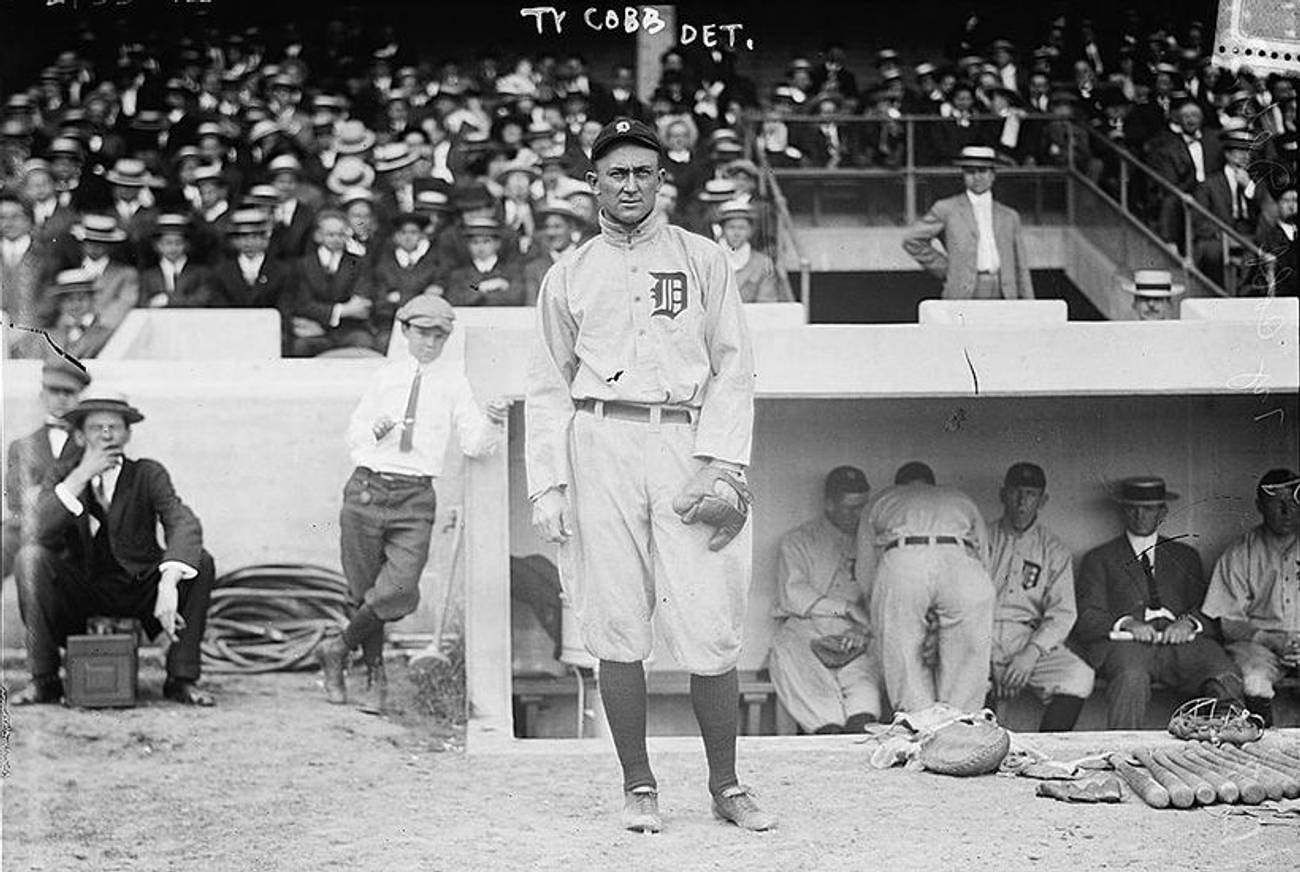

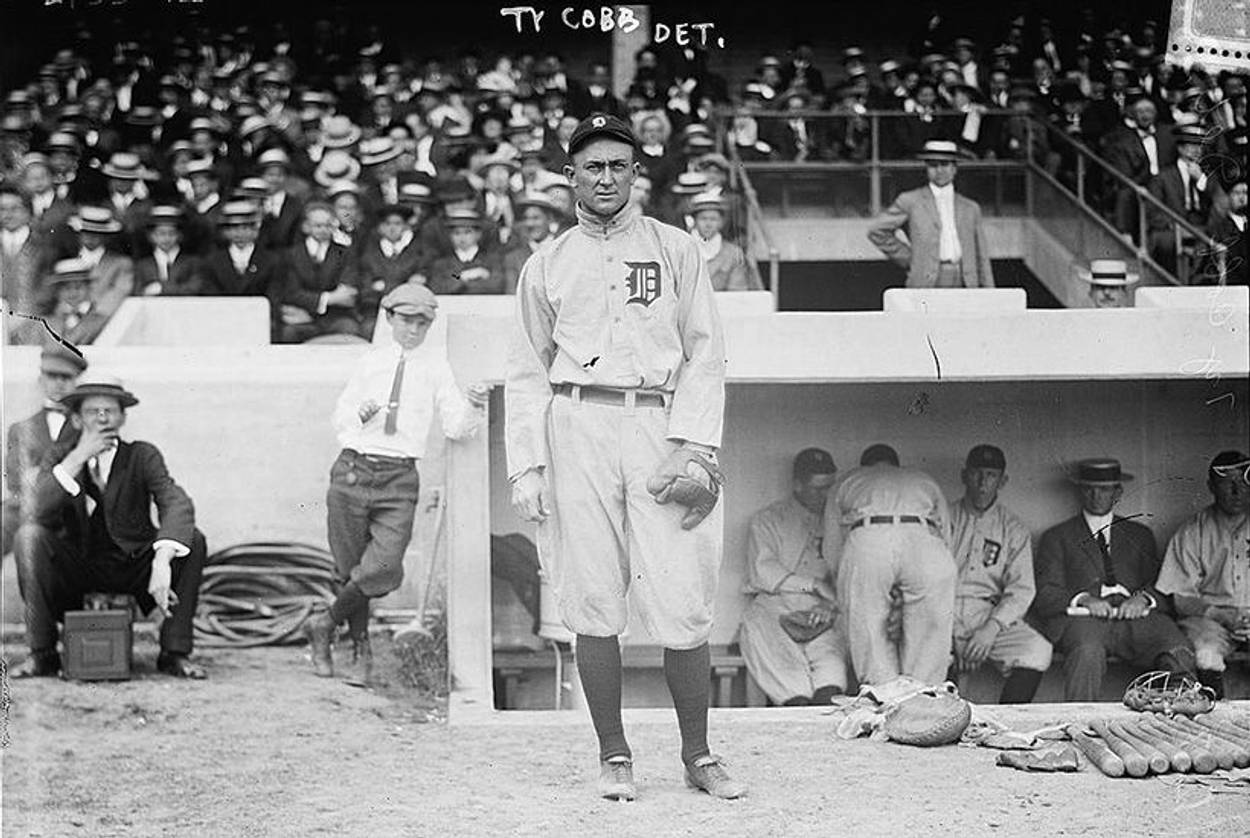

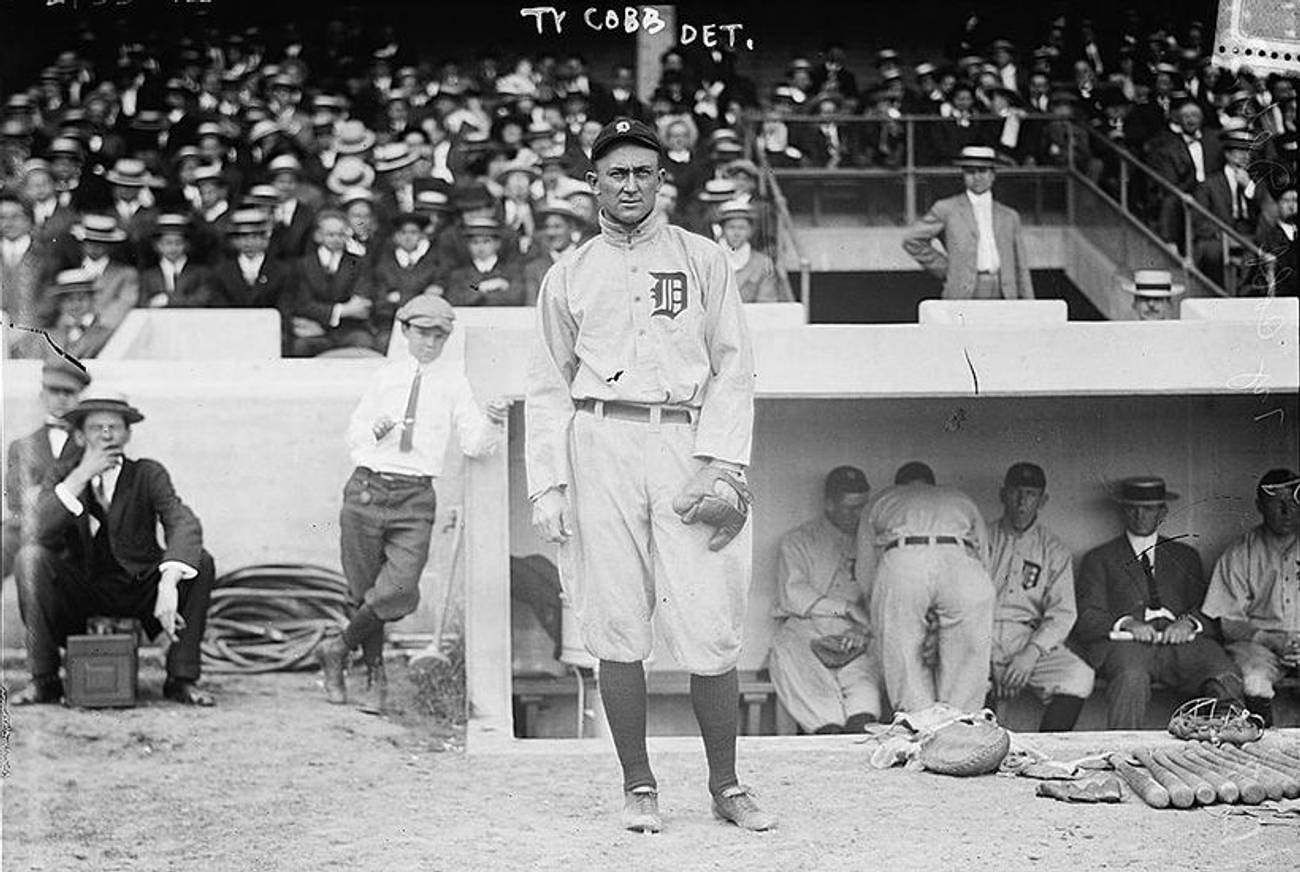

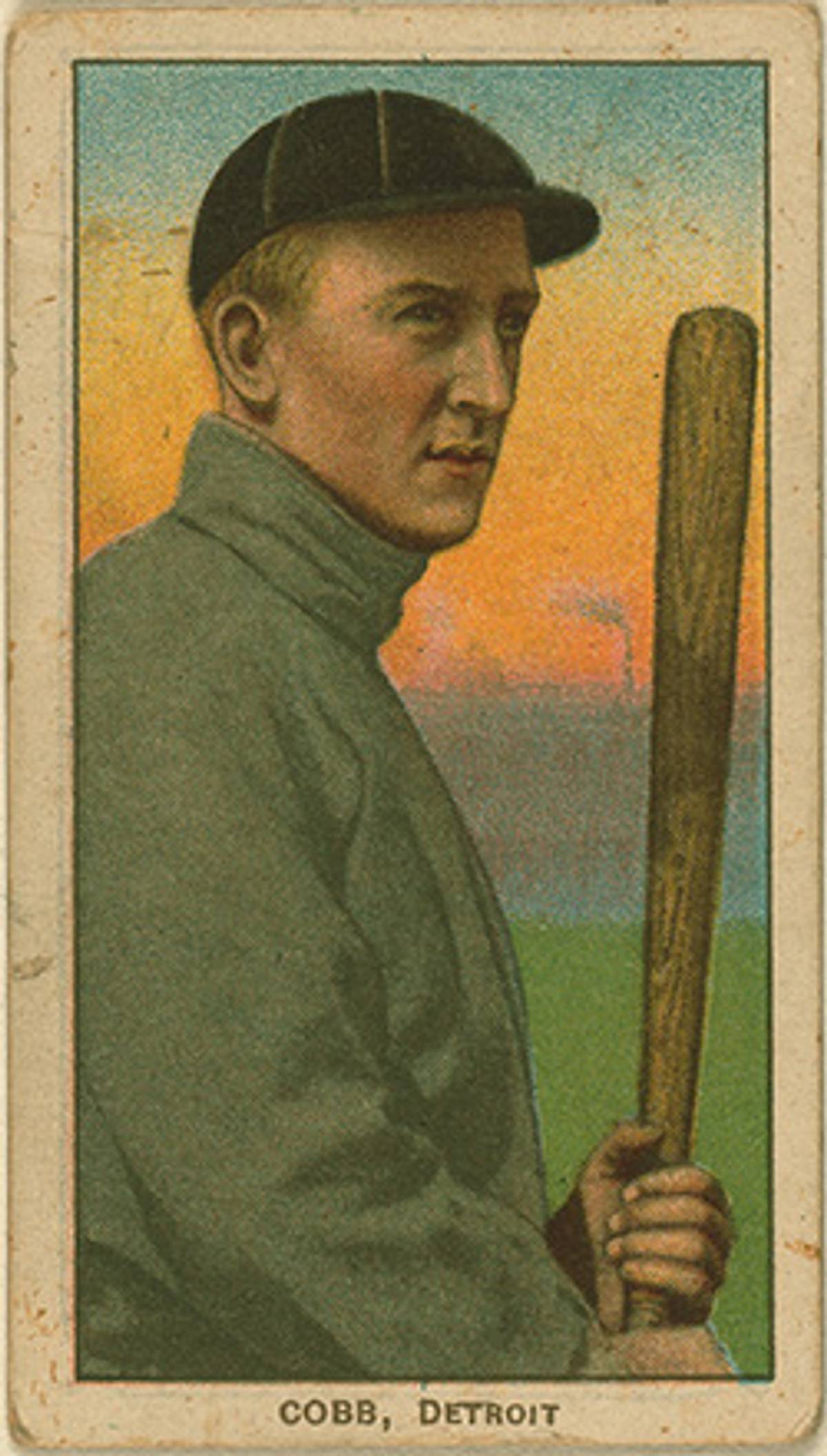

Ty Cobb has always been my favorite baseball player. Possessed of intense eyes and wearing the flannel uniforms that must have been exceedingly warm in the summer, Cobb choked up on his bat noticeably, to give him better control at the plate; in photographs, there is always a spot of wood beneath his hands. Those photographs are searing—Cobb’s gaze was piercing, as if always expecting the next pitch. And there was nobody better at baseball, the game and sport of it, than Ty Cobb. His batting average is the highest of anyone who has ever played, at .366. When he retired, he held nearly all the records that really matter: hits, runs, games played, stolen bases. And his preeminence was not a function merely of his earliness. Many of these records lasted throughout the long and triumphant 20th century, and some of them still stand today. He was part of the Hall of Fame’s inaugural class in 1936, garnering the highest percentage of votes for admittance. Cobb always seemed to fit well in those black-and-white newsreels, running the bases with manic speed, playing for keeps and immortality at a time when the sport was still raggedy and young, dead serious when the game was still a game. Al Stump, one of his most insightful but least reliable biographers, called him “the greatest and strangest of all American sports figures.”

Of course, several records were not Cobb’s to break: They belonged to his slightly younger contemporary Babe Ruth. These two great players were also very different. Ruth was gregarious and portly, thrilling crowds and upending the game’s foundations with his preposterous, anomalous power. A player on both the Red Sox and the Yankees, he has a legacy inscribed on two of baseball’s marquee franchises. Cobb perfected the game according to its old rules and standards; he played the same game as everyone else, he just played it better, for longer. He spent the bulk of his career with the Detroit Tigers and sowed fear and respect rather than awe and adoration. If the iconic Ruth moment is the trot around the bases after a ball sent into the stands, then for Cobb it is turning the corner at first and roaring into second base, spikes arched menacingly high.

And that was always part of Cobb’s appeal: the bat gripped tight, the glint and flash of violence and menace. Those qualities served Cobb well in between the lines of the baseball diamond, but they also infected his life outside of it. Nastiness tinctured many of his interactions, and he shared a racist edge with his times while also taking a perverse pride in slurs of a particularly mean and unsettling variety. There is no doubt that the language of prejudice came easily to Cobb—in a memorable quote Stump uses as an epigraph, Hemingway called him “the greatest of all ballplayers—and an absolute shit.” Charlie Gehringer, a Hall of Famer himself who played under Cobb during the master’s managerial tenure in Detroit, called him “a real hateful guy.”

Less discussed than his well-known antipathy toward black players was the fact that Tyrus Raymond Cobb was also an anti-Semite, and that on at least two occasions that particular affliction manifested itself on the field. Cobb’s anti-Semitism is so fascinating because it intersects with questions of sportsmanship and fair play, prejudice colliding with the protocols of a rough-and-tumble game trying to clean up its act.

***

Then as now there were very few Jews on the field, but one of them was a first-baseman from Philmont, N.Y., named Claude Rossman. Rossman broke into the major leagues in 1906, a year after Cobb, but quickly joined him on the Detroit Tigers and served as his table setter and enabler; as a proficient bunter, he aided Cobb’s reckless abandon on the base paths. His career was short, lasting only five years, but his 1907 season was a strong one that saw him emerge as one of the Tigers’ top players, cemented by a World Series where he outplayed his more famous teammates Cobb and Sam Crawford.

Rossman is remembered today not for his brief playing career, but for an incident involving Cobb that dates from the 1907 season. As told by Cobb’s biographer (and sometimes antagonist) Stump, the pennant race was tight, and the Tigers and A’s were deadlocked 8-8 in a 14-inning game that Cobb would later call the “most thrilling” of his career. In a canny move that Cobb likely had no compunction about executing, he told Rossman that Monte Cross, a player on the Philadelphia A’s, had called him a “Jew bastard.” Rossman, no doubt on a short fuse and far from hearing this for the first time, punched Cross and was immediately arrested. The scrum and confusion that resulted somehow redounded to the Tigers’ benefit, and the game was eventually called a tie on account of darkness (electric lights at stadiums were still far in the future). The A’s eventually lost the pennant, and a fabricated anti-Semitic comment was a deciding factor in giving the Tigers their first American League championship since 1887.

Cobb’s cunning and unmatched competitiveness are on display here as well. He fabricates an anti-Semitic slur knowing his Jewish teammate will overact but also that this overreaction will prevent a Tigers loss. The combination of incitement and gamesmanship is typical of Cobb and indicates the ambiguous role of language between the lines; the baseball diamond as both zone apart and microcosm.

Slurs and insults were not the only tools Cobb used to cut people down to size. He famously sharpened his spikes, intentionally honing the blade so that a slide into second base presented acute danger to the player on the opposing team manning that position; his nickname of “Butcher Cobb” attests to the success of this tactic and the fear it inspired. Many of the most iconic pictures of the “Georgia Peach” feature him sliding, spikes raised and menacing. As Cobb retired with the record for most steals in a season and for a career, this was a form of routinized violence. But only one player’s career was ended by Cobb, and he was born Michael Myron Silverman and went professionally by the name Jesse Baker. Silverman has that most austere of statistical profiles; one game played, one RBI registered, no official at bats. He is hardly in the record books at all, his career severed before it began by one of Cobb’s spikes on Sept. 14, 1919. According to Ariel Boxman’s Jews In Baseball, Baker went on to play a few more years in the minor leagues before moving to Los Angeles. It is impossible to know whether Cobb slid into second base particularly viciously because Baker was Jewish; Cobb needed no excuse to endanger another player. But Baker is a strange kind of casualty, a kind of minor offering at the altar of the cult of Cobb. Baker, a Jewish boy from Cleveland who left the clothing business owned by his parents to become a professional ballplayer, found himself excised from history by a player who had everything, but only because he always slid in, spikes raised.

Cobb’s anti-Semitism has been both affirmed by private remarks and in correspondence and disputed by the same sources. The Rossman and Baker incidents, however, are far more interesting than run-of-the-mill anti-Semitic behavior from the first quarter of the 20th century, a time when prejudicial attitudes were pervasive. They each exist in a zone of ambiguity, which is just another way of saying that they are complicated for having occurred in a sporting context, where competition and competitiveness and the drive to win constitute their own kind of morality. Davids to Cobb’s Goliath, these players were no match for the Georgia Peach. It’s so difficult to parse his general nastiness from his particular prejudice, because to compete is to be antagonistic, and sportsmanship is a way to make us feel better about the essential amorality of the game. In sports, as in life, we perennially want it both ways: to play without consequences but also with a sense of stakes. We want to be the type of people who value process, and yet we hopelessly care about outcomes.

Is it wrong to suggest that the “we” in the previous sentence reflects a particularly Jewish American quandary? Recently in this magazine, in a piece on the occasion of a new exhibition at the National Museum of Jewish History in Philadelphia titled Chasing Dreams and Becoming American, Jon Wertheim wrote of baseball, “the sport has become interwoven with the American Jewish experience.” Literary works as diverse as Bernard Malamud’s The Natural, Philip Roth’s The Great American Novel, and Eric Greenberg’s The Settlement all place the relationship between Jews and baseball at the center of things. As Martin Abramowitz notes, “the Jews who paid to watch, or hovered around radios, bars, sports pages as fans of the game, were absorbing America, being absorbed by America, and contributing to America.”

And yet, this was always a relationship more of quality than of quantity. According to David Spaner in Total Baseball, between 1900 and 1909 only five Jews played in the major leagues; that number increased to 13 between 1910 and 1920, and for the years 1871 to 1996, Jews constituted only 1 percent of total major leaguers. Sportswriters noted this particularly poor representation, and they tended to both celebrate so-called ethnic ballplayers for their accomplishments while also encouraging them to put aside any differentiating features. A New York Journal article from September 1934 describes this model of team-as-melting pot; “Greenberg is a Jew and his boss, Cochrane, is a Catholic, and there are other Catholics and Protestants and nonbelievers on the Club. Yet it functions like a well oiled machine.”

Hank Greenberg, whose career began in 1930, and who succeeded Ty Cobb as the star of the Detroit Tigers, was not so easily assimilated by baseball’s casually racist fan base. An icon of his people, the Bronx-bred Greenberg was also an exceedingly productive baseball player, who led the league in home runs four times and set a right-handed record of 58 in 1938. But there were the symbolic gestures as well; the debate whether to play on major Jewish holidays (no on Yom Kippur, yes on Rosh Hashanah, but he hit two home runs). Greenberg steadfastly supported Jackie Robinson when the latter broke into the major leagues, one trailblazer helping clear the way for another.

Being a proud and successful Jewish player in pre-WWII baseball meant being the target of nearly constant abuse. As Mark Kurlansky notes in Hank Greenberg, The Hero Who Didn’t Want To Be One, “while earlier players used their real names, many of the players of Greenberg’s youth changed their names to avoid the increasingly virulent anti-Semitism in baseball organizations, among fans, and in the press.” Greenberg broke into the major leagues in 1933, a perilous time for the Jewish people and an especially troubled one for American Jews. Kurlansky points out that while “almost any player perceived to have an ethnic background” came in for abuse, “the harassment of Jews was especially vitriolic.” As Greenberg would later tell the AJC, “Every ballpark I went to there’d be somebody in the stands who spent the whole afternoon just calling me, you know, names. … To them it’s a game.” Of course, baseball is nothing but a game, but Greenberg here addresses the problem of anti-Semitism with the language of sportsmanship. These fans violate the rules of fair play, and their offense is a sin against fandom as much as against the Jews.

Hank Greenberg and Ty Cobb were not friends, but Cobb respected Greenberg’s abilities, and Greenberg was in awe of Cobb’s on-field persona. It’s not necessarily clear that these things matter all that much, in the grand scheme of things. I’m always wary of the license claimed by things like art, or literature, or baseball, that they can solve our problems, but that we need to grant them immunity first. And yet, nine innings do provide a kind of window of opportunity, where the world looks a little bit less disfigured. Or, perhaps, where we can convince ourselves that is the case.

Ari Hoffman is a doctoral candidate in English at Harvard University.