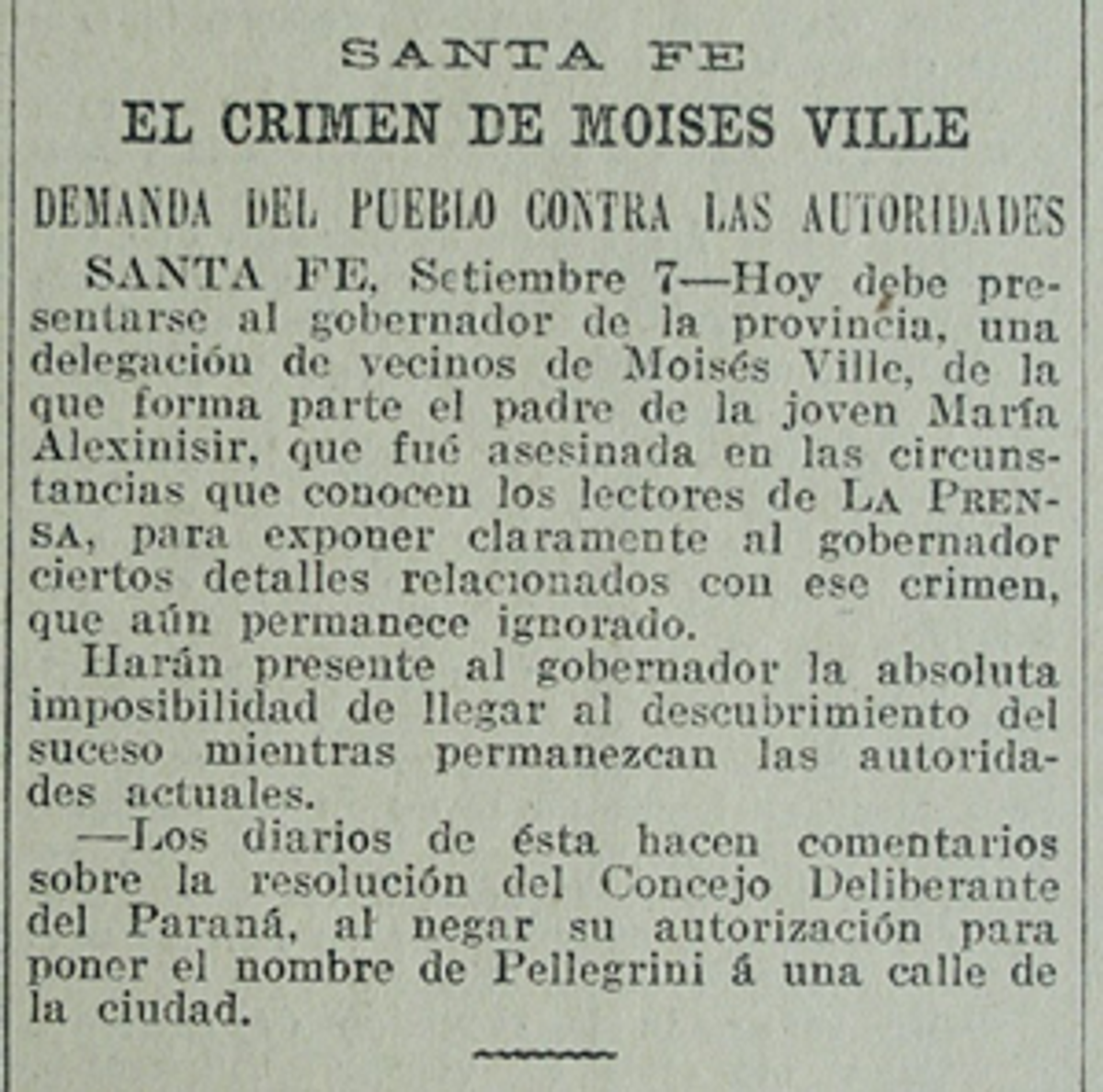

The Crimes of Moisés Ville: A Story of Gauchos and Jews

The long echo of a massacre on the Argentine pampas, and the multi-generational chronicle of Jewish life in its wake

On the wintry night of July 28, 1897, as the colony’s social situation got more tense and as Mordechai Reuben Hacohen Sinay’s delegation struggled against the limits of the JCA (Jewish Colonization Association) in Paris, a group of horsemen arrived at the door of Joseph Waisman’s house, near Moisés Ville.

A Russian family lived there, with four children born and raised on Argentine soil—the youngest, just 22 days old. The brick homestead set in the middle of the countryside now seemed small. This was also where Joseph, who looked older than his 30 years, ran a store.

The lead rider knocked on the door and waited, holding his breath.

Five years before, Joseph Waisman’s father had made the decision to leave Kamenetz-Podolsk with his family: Froim Zalmen Waisman was his name, and he feared for his four sons and his grandchildren. It was well known, in the time of the tsar, that Israelites bore military service as a special burden, after an 1827 law that had set their draft age up to 25. The tsar thought that was the only way to forcibly assimilate the foreign population, and he had organized a special force of khapers or official kidnappers who would steal away children and send them to be raised in youth battalions.

Influenced by the Argentinistas who spread through the shtetls—and knowing well the experience of Poles who had left from the same city—in 1892 old Froim Zalmen boarded a ship and left behind the tsarist cruelties. He brought his wife and three children with him, and he sent his oldest son, Joseph, with his wife Gitl and their three children, on another ship. In addition to trunks, suitcases, and baskets of food, Froim Zalmen brought a quilt that he requested special attention be paid to and from which he refused to be separated. Some weeks later, the Buenos Aires port workers would be surprised by the care this man would lavish on his quilt—little did they know that among the feathers were gold bars: Froim Zalmen’s return on the sale of his wheat mill in Kamenetz-Podolosk. Now all of his fortune and future were here.

When he arrived to Moisés Ville, his name converted into “Fermin Salomon” by immigration officials, the old Waisman met up with some of his former Russian neighbors. With his gold savings, he opened a store in Moisés Ville and helped his son Joseph to set one up just down the country road leading to Palacios. Waisman’s son lived some years there in that brick home, where he also had the store, and where he heard rumors about the colony’s founding and the hunger in the railway warehouses. It had all happened right there, in Palacios, in a recent past that nonetheless seemed distant. After they opened the two stores, they carefully wrapped and buried the leftover gold bars, to be used later.

So things went. For a time.

***

But the night of July 28, 1897, did come, unrelentingly, irreparably.

“That was a haunting night. The drunks came looking for wine … and my grandfather Joseph didn’t want to open the store to them,” says Juana Waisman, daughter of Marcos (Meyer) Waisman, one of Joseph Waisman’s children.

That boy, Marcos—then 8 years old—was lucky: He was with his brother Bernardo (Bani, 10 at the time) in his grandfather Froim Zalmen’s house, in Moisés Ville, where they went to school. They were the oldest of seven siblings and the only family members not at the store when the “savage, evil, criminal people” arrived, as Marcos’ daughter Juana tells it. Of all the people I could speak to, she had been closest to the events: She was 95 when I visited her in a nursing home where she spends her days—a manor where the wood floors creak and the old people are surprised to see visitors, a few miles outside the center of Rosario, the largest city in Santa Fe province.

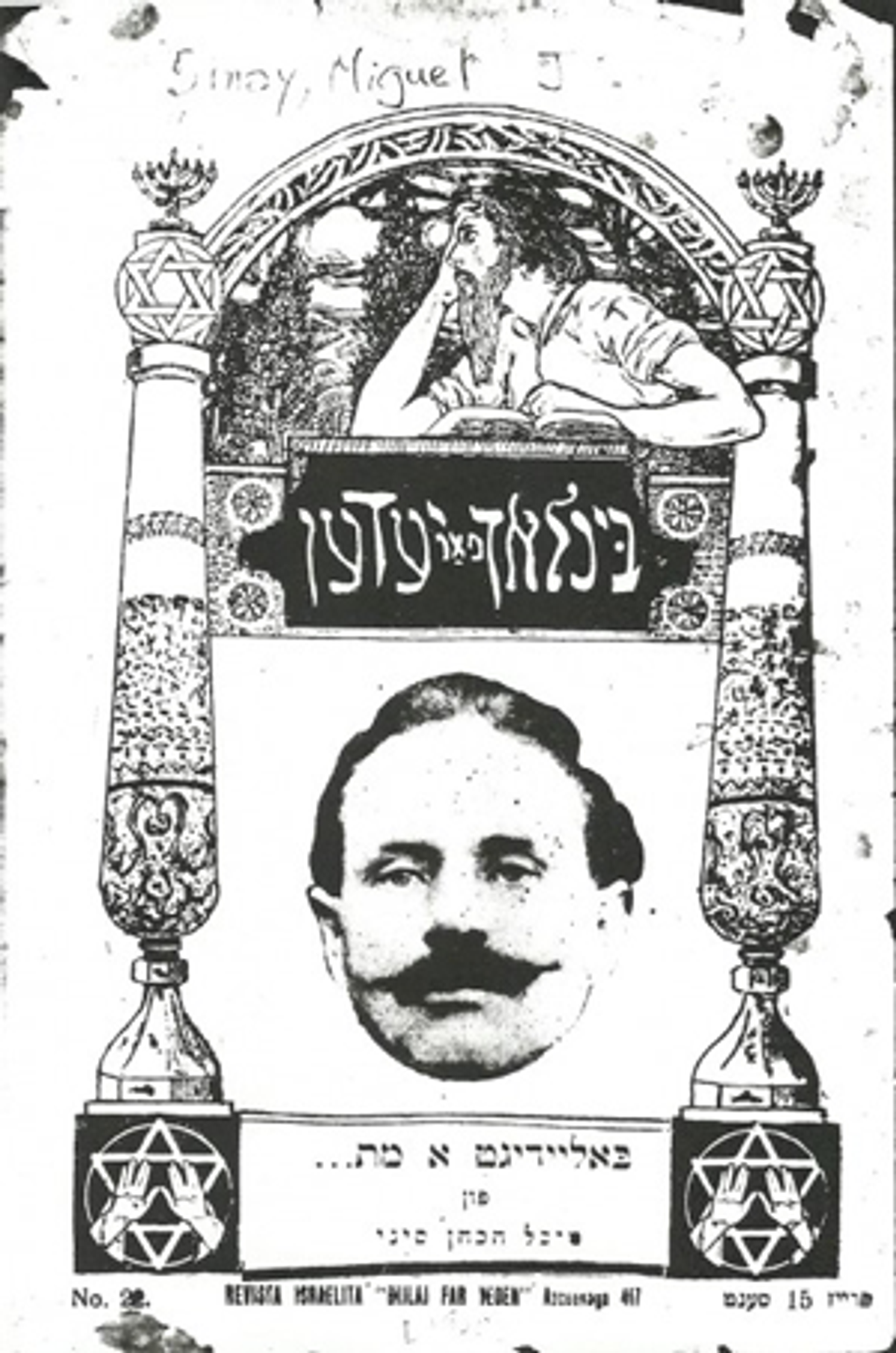

Juana had not read “The First Fatal Victims in Moisés Ville” (a 1947 report on the crimes), but she wasn’t surprised to hear from me that Mijl Hacohen Sinay wrote two pages—not a small section— on her and her family’s case, which had visited the deepest horror on the colony. “When night fell, the head of the family, Joseph Waisman, was about to close the store, while his wife, Gitl, was putting their four children to bed in one of the rooms,” wrote my great-grandfather.

The oldest of them was a child of 13, and there were two female twins, and a 6-year-old boy. After Waisman had closed the door he heard a loud knocking outside. He then went back to open the door and he saw some gauchos rushing in and was immediately stabbed in the heart. When his wife heard his screaming, she raced to the store from the bedroom, and the gauchos also stabbed her in the chest. The woman fell to the floor and bled there, in agony.

The next scene took place in the other room, where the gauchos killed the children. The oldest brother tried to stop them, but in an instant he had been dragged to the floor and his body was cut to pieces. The two girls were shot in their beds, and then stabbed in the heart and their throats cut. While the gauchos were caught up in the massacre, the smallest child silently stole from his bed, out of the house, and hid in the fields of tall grass.

When the massacre was complete, the gauchos robbed everything and disappeared without a trace. The neighbors found out about the incident the next morning. There may have been shouts, screams, and cries for help during the tragedy, but no one had heard anything, because the seven houses that made up the community of Palacios were separated by considerable distance. This is why none of the neighbors heard the victims’ calls. When the inhabitants of Moisés Ville went to Palacios—all together: adults, old people, children, women—as soon as they got wind of the tragedy, and saw such a pathetic sight as what they discovered in the Waisman house, they all fell to lamentation, men and women alike.

The place, like the small store, looked like a pogrom. Everything the gauchos hadn’t taken was strewn across the floor, broken and shattered, mixed with the blood of the lifeless bodies of husband and wife, with their terrible faces. The bedroom was worse, a butcher shop. The floor and windows where the children slept was covered in blood. The quilt was soaked. The oldest boy was on the floor, his body destroyed. The twins were like two slaughtered chickens, thrown onto their bed and painted in their own blood.

The victims were taken to Moisés Ville, where they were buried in the cemetery. During the funeral, cries and hysterical tears reached the heavens, from men and women who couldn’t resist fainting.

The tomb where the Waismans are buried is the longest of Moisés Ville’s cemetery. You might think a giant was buried there, but in reality the father, mother, daughter, and son were laid head-to-toe in a straight line. For some reason they are not in section 5, where the assassinated were traditionally buried, but instead in the older section, No. 6, where they occupy grave plot 6 in row 2. More than 120 years later, the Waisman grave has become a reference point—sometimes as a tourist stop: “Past the long grave,” say those who want to indicate directions.

But the stone still tells a poem of fear, brief as a haiku, in Hebrew: “Here lie the blessed/ Herr Mordechai Joseph son of/ Froim Zalmen his wife/ Gitl daughter of Moshe/ his sweet daughter Perl/ his son the boy Baruch/ who were killed by the hands of assassins.” (“Waisman” does not appear on the stone: the Jewish names are enough for the final passage.)

***

Now Juana Waisman’s blue eyes—lightly clouded—watch with the calm of a flat sea, while her words carry in their wake a distant resonance of Yiddish—of that same Yiddish that had raised her in an Argentine household where they prayed morning and night.

“They never found out anything,” she says. “There was fear! Because in Monigotes [a town near Moisés Ville] there was a jungle where criminals would hide out, and no one could point them out without risk of death. But everyone knew what was going on. Because those same savages had also killed in another town a cantor. … In those days people were afraid of bandits.”

Juana has lived, since her birth in 1916, the rise and fall of Moisés Ville, which she left 40 years ago, when she started to find herself alone, without more company than that of her husband Santiago, who ran the electric company in the village. With pride, she tells me that her husband had entered the company at 17 as a lowly worker and had left as its accountant, with a gold medal weighing 50 grams, in addition to being the ad honorem administrator of the hospital for 15 years and twice member of the bank’s board. Small-town things.

In the nursing home, her own children and grandchildren tend to lavish attention on Joseph Waisman’s ancient granddaughter. But she thinks about Moisés Ville; that is, about “Moishevishe,” as she calls it.

“Here in Rosario we’re one of many, but there we were someone. Whenever we traveled we’d be feted with a going-away party: Traveling was like a miracle, and they’d only let us go on the condition that we promised to tell all when we got back. We went to Israel, Hawaii, the Caribbean. … Such lovely things! And then later when we no longer lived there but came for visits, all doors would open and from every door they’d say hello. Now there’s almost no one left. Not anymore. That’s the history of my village and I’m used to it. After so many years … that’s how it is. It’s all true. I’ve lived it and I’m not 5 years old.”

That Moisés Ville, where Juana Waisman was raised, wasn’t as risky as the village where her grandfather had died. In the 1920s, the modest home grocery where the crime had taken place became a ruin that descendants would point out from afar. Since then things had changed: The gauchos and the Jewish colonists maintained friendly relations that eventually led to the rise of the Jewish gaucho, so well-known in these parts of the pampa.

“The locals spoke Yiddish better than we did; there wasn’t fear or discrimination,” Juana remembers. “By ear they’d sing Hebrew songs on their guitars: in-cred-ible!”

Was it Juana’s father, the “little orphan,” who brought to mind Noé Cociovich, the memoir writer? This colonial founder didn’t like talking about the crimes of Moisés Ville: His memoirs barely mention one or two events, off-hand. He doesn’t go over the Waisman crimes, but he does mention it when he speaks of a mysterious traveler who arrived at the end of 1897, “an older gentleman of fine carriage, robust, full, luxuriously attired, speaking several languages, including Spanish.” The man introduced himself as a shareholder in the JCA, saying he was Dr. Klein, of London, and he asked for kosher food. But the administrator, Michael Cohan, who had received him with respect, grew suspicious of him when he saw him toasting repeatedly with his beer, and licking his lips unabashedly. “You can tell a man, our wise men said, by his cups,” wrote Cociovich. The next day, Dr. Klein toured the sown fields, visited Rabbi Aharon Halevi Goldman, and “went to see the little orphan of the recently assassinated Waisman family, kissed him and gave him a five-cent bill … assuring that word of the tragedy had reached Paris and that he resolved to watch over him.”

(Of course, this was all a trick: Dr. Klein was a charlatan, neither doctor nor shareholder in the JCA—just someone who wanted to cheat the farmers out of their money by offering them false colonies in Montevideo.)

But, aside from this fraud, perhaps Marcos Waisman—Juana’s father—was that orphan. Juana doesn’t know about it, but she can say that her father survived and was raised with love by his grandparents, far from the shadow of the tragedy. He never looked back. He couldn’t. Instead, he had to work the fields and in a general store to provide for five children and raise them with good memories, like those that Juana recalls when she describes waking at 5 a.m. to drink warm milk fresh from the udder, or riding horses at age 6.

All of Joseph Waisman’s surviving children, Juana tells me, forged their lives in the same mold. Without looking back. Without allowing the massacre to drag across the generations. But there was one moment when the past became present. It was shortly after 1897, when one of Joseph’s brothers—who roamed the countryside of Santa Fe province in a horse-drawn carriage, selling clothes—stopped at a ranch to take shelter one cold night. The man tied up his horses and watered them, and when he entered the house, he was perturbed by the image, in a corner, of a fur-lined overcoat—a classic Russian cloak, just like the one that had been stolen from Joseph Waisman on the night of his murder. “I’ve forgotten that I still need to visit someone else around here,” he then said. And never returned.

“That was the criminals’ house!” Juana shudders.

By the time her Yiddish-recipe cake is nothing more than crumbs, Juana shows me that, unlike her father, she can look back. And that she had gathered a long family tree, with the history of the entire family, that she had photocopied and sent to 50 family members spread out across Argentina, the United States, and Israel. She was also the one who had the idea to place a plaque on the long Waisman family tomb, in Moisés Ville cemetery:

In memory of our beloved grandparents, assassinated in 1897

JOSE WAISMAN and GUITEL PERELMUTER

and THEIR CHILDREN PERLA and BABY

R.I.P.

August 1994

“We knew who was there, but the letters had grown faint,” she tells me, as if justifying herself. “And I thought that we had to put that plaque because I went to Moisés Ville cemetery out of obligation, every year, between Rosh Hashune and Yom Kiper”—and she doesn’t say “Rosh Hashanah” or “Yom Kippur,” as she’s speaking in her Eastern accent, just as from my grandmother’s mouth I had also heard, once, a very flat “Yom Kiper.”

Somehow, Juana took on the responsibility of transmitting the family’s past to the future. If the engraved letters were eroding with time, fading like Yiddish is, she made a decision to make history endure. To leave it as a legacy to those who, some time, in the days to come, could make them their own.

Juana sought and then found the support of the entire family. She had always been a woman with initiative: When she lived in Moisés Ville she invented and patented in Rosario a men’s garment bag, which she made at home with three seamstresses, and whose principal client was the local office of the Argentine Automobile Club. So, it couldn’t have cost her much to have a plaque made. And only after she had had it installed did she relax, as if she had paid a debt to those grandparents sacrificed in vain. There, before the old four-person grave, she would think on them and ask that her ancestors rest in peace.

“I would ask them to answer, to watch over us,” she explains. “They’re dead, and dead they’ll be, but I would still get things off my chest. And even though it’s been some time since I’ve been to the Moisés Ville cemetery, I already have the plot next to my husband. My children took care of it and bought it for me. Such good kids, right?

***

There’s another reminder from those days, almost as short and as striking as the one on the gravestone. And Eva Guelbert de Rosenthal, the director of the Museum of Moisés Ville, has it in her hands. In the museum office she goes over it again and again. It’s a binder full of photocopies, taken from a day book written by hand in Hebrew, which she reads from leaf to leaf, struggling with a script that’s nearly illegible:

1897

28 July. In the Palacios Station four souls were assassinated:

Joseph son of Zalman Waisman, 32 years

his wife Gitl, daughter of LeibBraunstein, 32 years

his daughter Perl, 8 years

his son Baruch, 22 days. The name of the mother

of Joseph: Jana and the name of the mother

of Gitl: was Shaia Braunstein

who lives in the city of Kamenetz-Podolsk.

After reading this, Eva looks exhausted. For some years now this photocopy binder has turned into a precious key for opening the door, normally stuck, to the past: The original is a precarious civil registry in which a traveler on the steamer Wesser (which brought the first Russian Jews in 1889) named Pinchas Glasberg noted births, marriages, and deaths. And also crimes. And that’s why Eva and her collaborators have written and expanded a code for deciphering what’s in the book, written in terrible handwriting, an elongated inclined script, superscripted and changeable. The writer’s Hebrew, ancient in manner, seems as if from biblical times. For each of Glasberg’s letters, the code offers three or four variants. In this way, Eva can take a word from the original and check it against her key letter by letter, as if she were an archaeologist before a papyrus.

“In these first notes, Glasberg put the basic facts: what happened, to whom, when,” she says. “Then he started to take down more details. Finally, each fact would take up several lines.”

The original Pinchas Glasberg document is exhibited in one of the museum’s display cases. It’s a worn tome, a Russian ledger, with columns headed with strange words in Cyrillic, which lose all meaning in the book’s reuse as a Hebrew civil registry. Starting in 1890—and for nearly a decade—Glasberg also kept track of breeding tables and milk production, accounts of tools and materials, and bovine markings.

A pair of portraits of Glasberg the colonist watches over the book. In one of them he appears with a long white beard and a small square hat that covers his head, holding a book (this book?) on his lap with a quill in his right hand. In the other, framed, Señor Glasberg is old and appears next to his wife, Mariem, and two of his six children—likely the oldest: Chaskel and Pachel. All are wearing suits. Pinchas sports a brimmed galera hat.

Glasberg was a pioneer who got personally involved in the construction of history: He served the community as a justice of the peace, presided over a nascent municipal council, and organized night watches to combat the sieges of bandits and cattle thieves. His work in the civil registry was so meticulous that the government of the province of Santa Fe accepted it as an official account of those first years; this is why, even if it is today exhibited in the museum, the book still belongs to the Commune of Moisés Ville. Glasberg’s last entry is dated July 11, 1899, the day the state’s registrar opened: That same day notes the birth of Naum Milstein, son of a 24-year-old merchant and a 23-year-old girl—both Russian—and the death of Samuel Rosen, a 7-year-old boy who was trampled under a horse.

In Pinchas Glasberg’s proposal there’s a desire similar to the one that fueled Mijl Hacohen Sinay to write the article about “The first fatal victims of Moisés Ville”: to tell the history. It’s a powerful desire, exercised by a shipwrecked sailor who imagines himself a conquistador, stuck in Finisterre and remembered every now and then by the civilized world. And as I write this, after more, much more, than a century, his work takes on unquestionable importance: as if in a race with history and forgetting, Glasberg captured those nodes of the great Moisésvillian novel, American and Jewish, that he recognized around him and lived. He couldn’t let it be lost from memory.

***

On the other hand, around 1897, massacring families was nothing new around the Santa Fe countryside, where echoes of a series of crimes still resonated—and appeared to have foreshadowed the Waismans’ own destiny.

It happened in 1869 in San Carlos colony, 120 kilometers to the south of the lands where the Poles would found Moisés Ville. San Carlos was populated by Swiss, Germans, Italians, and French—370 families; a little more than 2,000 people—and was an example of the rising gringo pampas. It was definitely different from the indigenous settlement of El Sauce, a few leagues from there, where Franciscan missionaries made peace with Indians, cultivated the earth, raised livestock, and lived in straw huts around a chapel. Evidently, the only interest a place like El Sauce could generate in the government of Santa Fe was as a military outpost within sight of land that only 10 years before had belonged to the Native Americans.

A lieutenant of the National Guard was in charge. They called him el indio or el negro, and he was named Nicolas Denis. He was the son of a Charrúa chief who had assimilated young and distinguished himself in battle against the savages who devastated the Santa Fe region. Denis had made a career, and now that he was over 50 years old, his word was law in El Sauce. This is why nobody was going to reproach his generosity with some old woodsman who showed up looking for pity and forgetting, even if he had a bad reputation.

Bartolo Santa Cruz was one of these. He was married, father to two young children, and worked at the canteen at El Sauce; in other words, he was stable. He wasn’t a nomadic gaucho anymore, but he had been, and he had been accused of taking part in a crime against a family named Guerin in the colony of Esperanza. That time, a lack of evidence had led him to be freed, and as soon as he could, he returned to his former captain, Colonel Denis.

It would seem that, in that local creole world, the canteen is a locus for tragedy, not just pleasure. A room with a straw roof, whitewashed mud walls, and dim light, where tabs are run over the year only to be settled over a few nights, where talk—of games, horses, contraband—flows with the wine; with melodies from an out-of-tune guitar and three women in search of money and company; and the gauchos on the rear cots snoring louder than the horses neighing outside. There’s no reason not to believe that Bartolo Santa Cruz’s canteen was any different.

And Bartolo owed 300 pesos to Henri Lefebre, native of Amiens, who lived in San Carlos and who also kept a small store. But there was no way to pay—even if there might have been the will: The canteen owner knew he was up to his neck in debt and that things were going to turn out bad.

That was when he joined his friends Jose and Mariano Alarcón, two brothers from San Lorenzo, two ferocious, lanky, dark men who weren’t afraid of death (the death of others) and who had been robbing, killing, and escaping for some time. The Alarcón brothers had been in custody twice: the first time, in prison; the second, in Northern Territory, where they were part of a battalion with heavy discipline and hardship. They managed to escape from both those hells. When they got home they were received with meat and dance by the handful of friends they still had, but after some time, as the devil would have it, right there in San Lorenzo, they killed again. They stabbed two people and also robbed their money and clothes. That was enough: Their own uncle turned them in to justice. They fled to friendly territory where they knew they could find refuge: El Sauce.

And there they were recruited by the barman Bartolo Santa Cruz. What did he offer them to convince them to stain their hands in blood the night of Oct. 15, 1869? Wine and liquor? Money and clothes? Loyalty and protection?

Julia Cornier de Rey, an old neighbor in San Carlos, declared in the trial that on the night of the crime she had gone out to collect some herbs to make tea for her daughter who wasn’t feeling well when she came across her son Francisco, the blacksmith. They walked together along the dusty street, where they met three gauchos on horseback near the Lefebre ranch. The witness said that on her way back she saw the horses tied up in front of the store. One of the gauchos stood in front of the door, worried. The other two, inside, were leaning on the counter and speaking with the owner of the house. So said Señora Cornier de Rey.

Waiting outside was Mariana Alarcón; he was 18 at the time. The two inside the Lefebre store—where the family also lived—were his brother José Alarcón, 22, and the local storekeeper Bartolo Santa Cruz.

And they committed the massacre.

They grabbed their knives and used them with precision, as the instruments they were meant for. They didn’t flinch before their victims’ terrorized eyes, or before their desperate last pleas, even as they were dying. Then, before leaving, they stole everything they could.

Some hours later, still in the dark of night, another French colonist discovered the scene: When the others arrived he was still crying, “Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu!”

In the morning, the doctor arrived. Everything was upturned, chaos bathed in blood. Including the bodies. The doctor noted, in his registry:

Enrique Lefebre, French national and businessman, received four stabbings, two on each side of the chest, one between the 3rd and 4th right rib and below the chest, another between the 4th and 5th left rib, another between 5th and 6th right side; all of these wounds are deep but it cannot be determined how deep due to the swelling on the side, death must have been immediate.

Lefebre’s wife shows a stabbing a little above the breasts that pierces the sternum and cuts the main branches of the aorta; she has another stabbing in the left side of the chest toward the heart, another wound in the right cheek of her face, death must have been immediate.

Next to Lefebre’s son I found the body of a 10- or 11-year-old girl, servant of said Lefebre, Italian national, named Jeroma. She shows stabbing in the left side of the stomach, piercing the chest and exiting through the shoulder, death must have been immediate.

Nonetheless, the assassins had left little Luis, Lefebre’s 7-year-old son, alive. He had hidden and then recounted how Bartolo Santa Cruz had been there along with two others.

The boy’s tale infuriated the colonists. The Lefebres weren’t the only victims, and livestock theft, abuses, and assassinations tended to go without punishment. And when the sun shone the day after the crime, the gringos marched on El Sauce intent on exacting revenge. They were 150 men. They were armed.

They were lucky: Fog covered them and no one saw them before they were at Bartolo Santa Cruz’s ranch, enraged. But Santa Cruz wasn’t there. So, they went on to Negro Denis’ ranch, where he tried to call them off, but they wanted nothing less than the canteen-owner’s head. They warned Denis that if he didn’t hand over Santa Cruz, they’d deal with him instead. There was no going back. The mob was determined and he was more alone than ever; the town’s Native Americans had gone hunting in the north and El Sauce was empty.

The gringos didn’t hoard resources: They set things ablaze. With dry wood and fuel they started lighting fires to burn Negro Denis’ ranch. He ran, frantic, to take refuge in the chapel, waving his sword at the masses who tried to cut off his path. He may have killed someone; once inside the church he noticed his sword stained with blood and heard how the tumult grew outside. In the confusion, his daughter Marta was wounded in the arm, and a neighbor was killed. Denis had taken the precaution of wearing a chest plate to protect himself from bullets, but when the bloodthirsty gringos started to burn the chapel, he had to come out, where the chest plate was useless.

Surrounded by the others, seeing too closely the hatred in their eyes and understanding that their strange cries were an inevitable song of death, Denis fell under a single hatchet blow that opened his skull.

Later, over his prostrate body—lying still, as if welded to the thick vegetation—the Native Americans, who returned after sunset, swore vengeance.

In a few short hours, all of the inhabitants of the region (gringos, natives, and gauchos) seemed on the edge of toppling a domino of revenge, but on Oct. 18, three days after the Lefebre family massacre, the provincial governor Mariana Cabal arrived trailing 600 soldiers to pacify the situation. The incident held sway three months later when, in January 1870, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, in his capacity as national president, visited San Carlos during his tour of the colonies to confirm the peace.

Nonetheless, some never saw this parade. The same day that the governor left San Carlos, a rural militia pursued one of Lefebre’s friends, who had become the last of the colonists accused of the crime against Negro Denis—another nine people had already been detained. Michel Jeremie Magnin, 25, born in Charrat, Switzerland, fled south but was caught on the banks of the Carcarañá River.

Faced with and surrounded by the authorities in front of him, Michel Jeremie Magnin knew his fate. He realized that his brother Jean, who had hanged himself from a beam in Esperanza, had not been, in the end, so wrong. And that he’d never escape the grassy plains where none of his dreams were meant to be fulfilled.

“Give in!” shouted the patrol, closer and closer.

Michel Jeremie Magnin looked at them for the last time, brought his Lefaucheux revolver to his mouth, and pulled the trigger.

***

When I arrive in Palacios (near Moisés Ville) in search of the story of the Waisman family crime, I find a town of barely 600 inhabitants, a sleepy town. During the trip from Moisés Ville, after passing through a rusty car cemetery along the route, I hear the driver complain about the road—the same surveyed by the Italian farmers and first Poles so that they wouldn’t get lost—needing new asphalt: Accidents are frequent and cars fly. Once in Palacios it’s not easy to recreate in my mind a quadruple crime like that of 1897: so much silence, such a smell of flowers.

Eva Guelbert de Rosenthal, the director of the Museum of Moisés Ville, is my guide, and she leads us to Berenstein, the last Jew of the village, only to discover that he’s ill, bed-ridden, and so it’s his wife who hands over the keys to the cemetery and the synagogue. As such the visit to Palacios is a complete tour.

We then visit the temple, a building where the forged iron Stars of David blend into the landscape of the ranches. The doors creak and the light kicks up dust. Inside everything has been frozen in time. I don’t know the last time there was a celebration, but on the altar a book lies open: It’s written in Hebrew and Russian, and in the footer it’s written that it was printed in Vilna, Lithuania, in 1883.

Some meters further, the famous Palacios station, where the pioneers first settled, is now home to three families. It’s incredible that after the boom and bust, the station should serve again as refuge for those in need of shelter. After passing through some clotheslines, I find myself on the sidewalk, with grass bursting through the cracks. A clock has stopped sometime after 4:30, and a poster reads “BE COMPASSIONATE WITH ANIMALS.” Even further, the station sign can barely be made out among the vegetation.

Still, across from the sidewalk there’s movement: With the rattle of metal plates, a machine moves and a truck awaits. The men enter and leave, and one, wearing work clothes, comes to meet me. His name is Lucas Bussi, and he invites me to the granary, where a giant mountain of seeds is rising up to the ceiling, being fed by the machine, which spits them out forcefully. Bussi takes me to an overly small office, where we shout at each other over the noise of the machines. He tells me that I’m in an animal feed factory and that the work there never stops. And he surprises me by saying that he is the vice-president of the commune, a loyal socialist and supporter of the governor, Hermes Binner—another descendent of colonists, born in Rafaela.

“We want to resurrect the town,” he enthuses. “And attract people to open a new work front, because we’re lacking for labor: There’s just the commune and the grain factory. But there was a hotel here once! There were cattle auctions, and people would come from all around.”

He had never seen it himself: He admits that those were things his father-in-law had told him, but he speaks of it as his own golden age. When we go back outside, before saying goodbye, Bussi waves to another man, riding up on his horse. It’s a old gaucho with a silver ponytail. After my question, Bussi and the gaucho debate the Polish pioneers. That this wasn’t the granary where they hid; that it was some meters over that way, and is gone, says the old man. Bussi insists it was this very same one. It wasn’t. It was.

“It was elsewhere, that’s what my grandpa used to tell me. This granary was built in the 1920s … if I’m remembering right that was where the trains from Chaco would unload,” the old gaucho said, ending the debate. He’s 85, after all.

“And did your grandpa tell you anything about the crimes?” I ask.

“Oh, those were the early days,” he says. “First the gringos came. And among the gauchos there were killers, guys who lived by robbing, who rode horseback and stole … but now the gaucho isn’t like that anymore. There aren’t any of those left. There aren’t gauchos at all! Before, there was Mate Cosido, Gauchito Gil, Vairoletto. They used to attack people and fight against the tyranny.”

“And who was in these parts?” Bussi asks.

“Round here there was a guy they called Francisco Ramirez,” the old one says after some thought. “But about the Waisman family, nothing. Not much to tell. On the other hand,” he says, “there are lots of stories about Jews. Look: a joke. Out here the priest and the rabbi were always testing each other. If the priest bought something, the rabbi did too. If the rabbi bought something, the priest did too. The priest built a house, the rabbi built one exactly the same. The priest planted some trees, the rabbi, too. Then the priest thought about it, and said, ‘He’ll have trouble imitating this!’And he bought a car and had it blessed. The next day the rabbi arrived with 10 men and a new car. Then the rabbi blessed his car, named it … and cut off the exhaust pipe!”

***

Unlike the assassins of the family of French colonists Lefebre—who were eventually caught—the perpetrators of the Waisman family crime had good luck: No one even remembers their names. Their eternally masked faces make it possible to think that perhaps they weren’t gauchos at all, but Europeans; colonists who chose to forgo their mission of sowing the earth in favor of sowing terror. That’s at least the theory of Joseph Waisman’s great-grandaughter, Etti Waisman, as she describes it by phone from Israel.

“My uncle Jaike told me Italians had killed the family during a robbery.”

For her, the crime of her ancestors is a distant memory, lost in the past, and what difference would it make now if the bastards were Italians, Native Americans, or gaucho bandits? But the story she’d heard went “Italians” and not anything else.

Etti’s grandfather Isaac Waisman (one of Marcos’ brothers, old Juana’s father), was a 1-year-old at the moment of the family massacre. His survival was an accident since, it’s said, he stayed hidden under the bed during the action. His granddaughter Etti keeps a warm memory of this grandfather, and she was excited when during a visit to Moisés Ville—after 48 years of living in Israel—she discovered her initials, “IW,” painted on her old house.

“We knew the story of the family crime, but it never really sank in,” she explains now, by phone from her house in Be’er Sheva, in the south of Israel, where she emigrated to as a child. And, almost as if she had heard Juana Waisman talking about her own father, she added, “My grandfather Isaac was a strong person who got on with things. Isaac Waisman had left the past behind enough that my grandmother Mañe, who knew him in Santiago del Estero, also didn’t know about his family tragedy.

“He was a popular man, but severe!” she remembered one Sunday noon when we were having a lunch of fish with yams, potatoes, onions, and carrots.

Like him, she lived for several years in La Banda, a minute from the provincial capital. My grandmother’s father, Menajem Mendel Perelmuter—a miller from the Russian shtetl of Lanowce who became a furniture salesman here—arrived in Argentina in December 1924 and marched directly to the province of Santiago del Estero, where some of his sons and friends had already settled. In the middle of summer, poor Mendel thought he was in Africa: He cut off his beard and stored his coats, and found some solace reading the daily Di Ydische Zaitung. My grandmother had her own family there. But in 1970, when her sons were already studying in Buenos Aires, she and her husband (Moisés, son of Mijl Hacohen Sinay) also decided to go and settle in Buenos Aires.

In some ways, without being close to any particular colonies or near a university, the suburb of La Banda—which is now part of the city of Santiago del Estero—had been converted into the home of a small Israeli community, and that’s where Isaac Waisman went as well. A betrayal had obliged him to change homes when he found out that his partner, a butcher, was cheating him: Isaac supplied him with meat from Moisés Ville but was underpaid for it. The swindle didn’t last long. When Waisman found out, he decided to open his own butcher shop elsewhere.

“There were two kinds of Jews, as always, and he was one of those unlike us,” my grandmother goes on. “But I can’t remember what we were on about … was it that stuff about the village?”

“What stuff, grandma?”

“Problems … There’s always problems to fight over: Who was more Jewish, who was more Zionist, that sort of thing …”

“But he was a popular guy, though?”

“Yes, popular … but severe.”

“Did you ever go to his butcher shop?”

“I never ate much meat, but I probably went once or twice. What I remember is that he was an excellent butcher, with his white vest all bloodstained. … That Waisman was popular.”

There was no way to get through: My grandmother wasn’t going to tell me anything about the crime. But I do think, as I write, that that was one of the strategies Isaac Waisman used to protect himself from a painful and inexplicable past.

Apparently, the fugitives of Moisés Ville have been forgotten, and only the traces of their bad deeds remain. Still, one of them passed into history thanks to the writer David Goldman. In his book Di iuden in Argentine (Jews in Argentina), the first noteworthy book about the local community, published in 1914, he wrote, “Especially feared back then was the famous bandit Coria, or as he was known, Coria mit de matikes (Coria with a hoe). He was wide-boned, naturally strong. His very presence caused people to tremble in fear. He had 12 children, all assassins. And wherever there was tragedy, they were to blame.”

This bandit’s relation to the crimes of Moisés Ville is clear: Goldman writes of him on the heels of a number of cases. Then I learned about another Coria, named Federico, who on Feb. 19, 1902—five years after the Waisman family crime—was sentenced by the Tribunal Superior of Santa Fe province to “imprisonment for an indeterminate amount of time,” for having killed one Remigio Zarate. That, and only that, appears in a brief two-page report in Santa Fe’s provincial archives, where I went in search of hints to the Moisés Ville crimes. I also found a report there on the Lefebre family crime.

There were two kinds of Jews, as always, and he was one of those unlike us.

There’s not much time to lose at the archives, open only in the mornings. On my first visit I discover that it’s dusty, dark, and silent. A colonial house with high ceilings and large rooms, once inhabited by the brigadier Estanislao Lopez—a caudillo who governed the province for 20 years—and which today shelters, on the roof above one of the staircases, a nest of squeaking bats.

“We can’t get rid of them; the exterminator can’t be bothered to get up there,” one of the staff tells me that first day. I imagine that on the other side of the roof’s wooden rafters there must be hundreds of critters. Their cries, amplified in their multitude, are magnificent, even at 8:00 in the morning.

For a few days I dive into the small stores, set down on ancient paper, which make up the larger history of the province. A silent staff member leaves me a few thick tomes, bound in rough leather: She brings them in a shopping cart and places them on the robust table. Then she leaves, without saying a word.

In the archive there are more than a thousand meters of documents and books; they intoxicate with their sweet, humid smell of history. Ghosts dance on each of the pages I review. I read registries about the construction of a train station in Moisés Ville—different to the one in Palacios; I learn about the complaints of the French, English, Spanish, and Italian consuls, about the mistreatment and vulnerability of their charges; I study court records on serial crimes and commercial reports on agricultural life.

Otherwise, Santa Fe is a quiet city where days pass languidly, absorbed by administration and bureaucracy, and invaded by various plagues: flies, cockroaches, mosquitoes, official stamps. Bats.

But about the Moisés Ville crimes, nothing. It seems like a curse. Judicial records from the Provincial General Archive end at 1888, just one year before the arrival of the Polish pioneers and the first assassination—that of David Lander. From then on, and up to 1915, haphazardness rules: Very few documents were saved. The leads I’m following aren’t in the Rosario Courthouse, nor in the Julio Marc Museum, in the same city, where there are other files from other jurisdictions outside of San Cristobal, where Moisés Ville is.

My last hope is in the General Archive in Tribunal: the provincial court’s main repository, also in the capital. There I begin the process, which all police-beat reporters know well, of requisitioning a file and arriving to claim it—not for nothing, in front of the entry tables at these tribunals there’s a long row of typewriters to write notes and more notes. One concession is made for me: The director of the General Archive greets me in her office, a little cell covered in papers and folders, where the humidity has peeled off a part of the wall and the provincial flag withers in the corner.

After chatting for a few minutes, I understand that the bureaucracy is implacable.

The penal code calls for destroying misdemeanor records every three years; tickets, every five; convictions, every 15; and sentencing every 20; and before shredding, edicts are sent to different institutions to search for related documents. The records are catalogued according to the year they enter the registry, not according to the year of the start of the case, such that if the document about the Waismans still existed, it might not have been noted in 1897 but in whichever random year it went into the archive. As if to get to the history you needed to belong to a club of initiates. The fight against forgetting goes on at the General Archive of the Tribunal with the digitization of lists, indexes, and reports; and with conservation of all documents dated 1993 and on. Meanwhile, the Provincial General Archive has been sent all reports up to 1915. But the whereabouts of documents dated after 1888 and before 1915 remains a mystery, only mentioned on occasion at the Estanislao Lopez house. I left defeated, beaten by the indolence of a distracted state.

The report on the Waisman family quadruple crime—much like for each and every case I’ve written about here—seems to have been destroyed without a trace.

“The problem is always space,” says the director of the Provincial General Archive, the historian Pascualina De Biasio, back at the Estanislao Lopez house.

Surrounded by the portraits of provincial heroes, she explains to me how documents require building infrastructure that isn’t often planned for.

“Given priorities and urgent matters, public policy doesn’t always coincide with needs, and this is how documents end up dispersed across the ministries,” she says. “In Argentina it seems that with the fever for the new comes contempt for the old.”

***

Given the absence of archives and reports, as if there had been some kind of massacre, all I can feel is indignation and astonishment.

Which is the same that Gabriel Braunstein, another of the great-grandchildren of the assassinated Joseph Waisman, feels when he pauses before his ancestors’ tomb. Gabriel, a nuclear physicist who studied at the Balseiro Institute in Bariloche and who has lived and worked in the United States for more than 30 years, knows more about the family than anyone else. With his passion for genealogy and the attention to detail of a scientist, he has worked to uncover his family tree, a labor that began years ago and is yet to be completed, and which included trips to Eastern Europe and interviews with whichever family member he could find. And that the eldest son of that colonist, Jaime Braunstein, inscribed his name in the dark history of Moisés Ville in the 1920s, when he killed a commissary who had seduced his wife, a mixed-race named Carmen Gorriz. After getting out of jail—where his crime would have made him respected by other delinquents—Jaime committed suicide in 1934, perhaps thinking of her.

“When I stand before this tomb I feel a mix of indignation and amazement,” Gabriel tells me by email. “Indignation because they were killed and no one ever found out by who (or they didn’t want to know). And amazement because it’s a small miracle that I should be standing there, and because the children got ahead, despite the tragedy, and lived normal lives.”

He knows better than anyone the Waismans’ roots and the exact family structure: On that dark night of July 28, 1897, in the house were Joseph and Gitl, the mother and father, both assassinated; Perl, an 8-year-old girl, assassinated; Baruj, a 22-day-old baby, assassinated; Wolf (or Adolfo), a 3-year-old boy who escaped to the brush; Isaac, the grandfather of Etti Waisman but at the time a 1-year-old baby, who stayed under the cover or under the bed and survived; and Raquel, a 6- or 7-year-old girl who was wounded and who, passed out or playing dead, eventually escaped and became Gabriel Braunstein’s great-grandmother. Away from that scene, staying in his grandfather Froim Zalman’s house in Moisés Ville, the two oldest brothers were sleeping, ready to go to class the next day. They were Marcos (or Meyer), 8—Juana Waisman’s father—; and Bernardo (or Bani), 10.

“Raquel, who was 6 or 7 when she was wounded in the massacre, became a vivacious woman, with a lot of personality and character,” Nelly Menis, Gabriel Braunstein’s mother, tells me on another occasion, when we had coffee around the corner from AMIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, or Israeli-Argentine Mutual Association, the largest Jewish organization in Argentina), where she volunteers at the library. “Raquel was my bobe (bubbe), she was tall and big, like her brothers, and on her birthday 25th of May, she would make empanadas and barbecue for everyone.”

Nelly, Gabriel Braunstein’s mother, describes herself as an “octogenarian who’s not so octogenarian.” She’s agreed to share some of her memories and so starts with the most pleasing: vacations at her grandmother’s house, her own work as a schoolteacher in rural Virginia, 17 kilometers from Moisés Ville, her marriage by moonlight and to the sound of a string band; and her second life in Buenos Aires, with her accountant husband.

And she talks to me with great love for her grandmother named Raquel, who had a guardian angel in that house of doom, but whom she lost at 44, when she came to Buenos Aires to care for a sick daughter and ended up herself with a bad flu that took her to her grave. That was the first time Nelly faced death. And that’s the traumatic experience she can speak of, much more so than the quadruple crime—just like for Juana Waisman and Etti Nachum—which seems a thing of the past, thanks to her grandmother’s will. Like the other survivors of the massacre, little Raquel also looked forward: She married at 14 and had six daughters.

“Many things I’ve learned in life, and which by chance I never mastered, she taught me,” says Raquel’s granddaughter Nelly. “For example, sweeping the edges and corners, because that’s where you know if a house is clean or dirty; or to clean plates thoroughly.”

At some point, just before finishing her coffee, she thinks of a detail, a tiny detail, that moves me and distracts me from what she says after:

“I still remember my bubbe’s fat arm when she hugged me, and also that she had a scar on her neck, from a wound she got the night of the assassinations.”

If the gash had been deeper, there would have been five victims—and that long gravesite in the cemetery that much longer. Instead, little Raquel survived. And life went on.

The scene after the massacre, no less bloody, is described by David Goldman, the son of the pioneer’s rabbi, in Di iuden in Argentine. It reads: “The next day, when they opened the door to the store, they found the whole family sacrificed. A disconsolate girl was crying in her mother’s chest: ‘Wake up, mama, I’m hungry!’ And they couldn’t pull her away.”

Translated from Spanish by Matthew Fishbane. Excerpted from Los Crímenes de Moisés Ville (The Crimes of Moisés Ville) published in Spanish by Tusquets Editores.

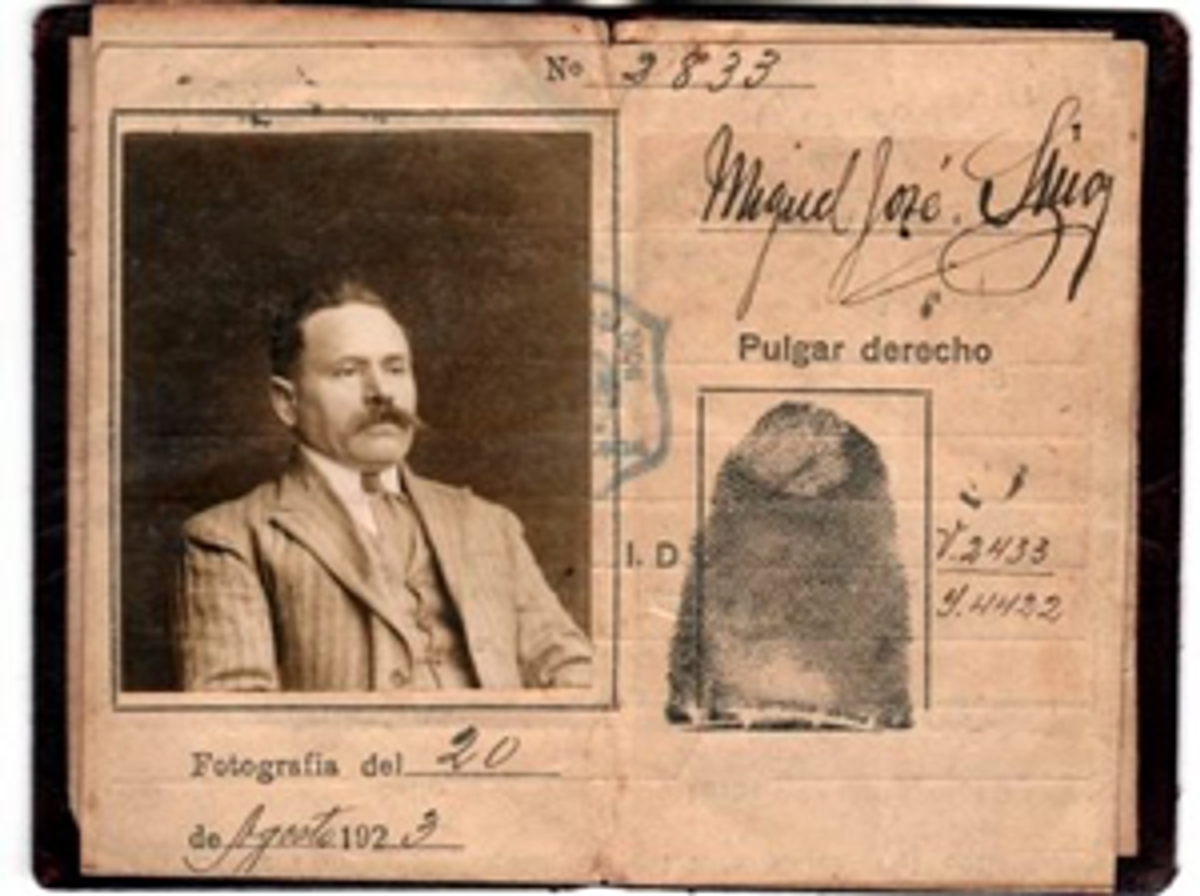

Javier Sinay, a Buenos Aires-based journalist, is the author of three books, including, most recently, Los Crímenes de Moisés Ville. The book will be published by Restless Books as The Murders of Moisés Ville in February of 2022.