Is Mr. Sammler’s Planet Still Part of the Literary Cosmos?

Sometimes art isn’t nice

It’s June 10, 1985. I can be sure of the date for reasons that will become clear. I am in the office of my American agent, high among the topless towers of Manhattan, to discuss what we might do to whip up a bit of interest in my second novel. It is my first trip to New York, so I am trebly energized—by thoughts of literary fame in the only city that offers it on a scale sufficient to my ambitions, by the vertiginousness of the urban spectacle, and by the courage I have shown navigating the perils of those cavernous streets below. “Don’t meet anyone’s eye,” I’d been warned before I left England. “If they ask for your wallet, give it.” By “they,” the people concerned for my safety meant “muggers,” and by “muggers” they mainly meant—this is nearly half a century ago so I hope that in the name of historical verisimilitude I can say it—Black people.

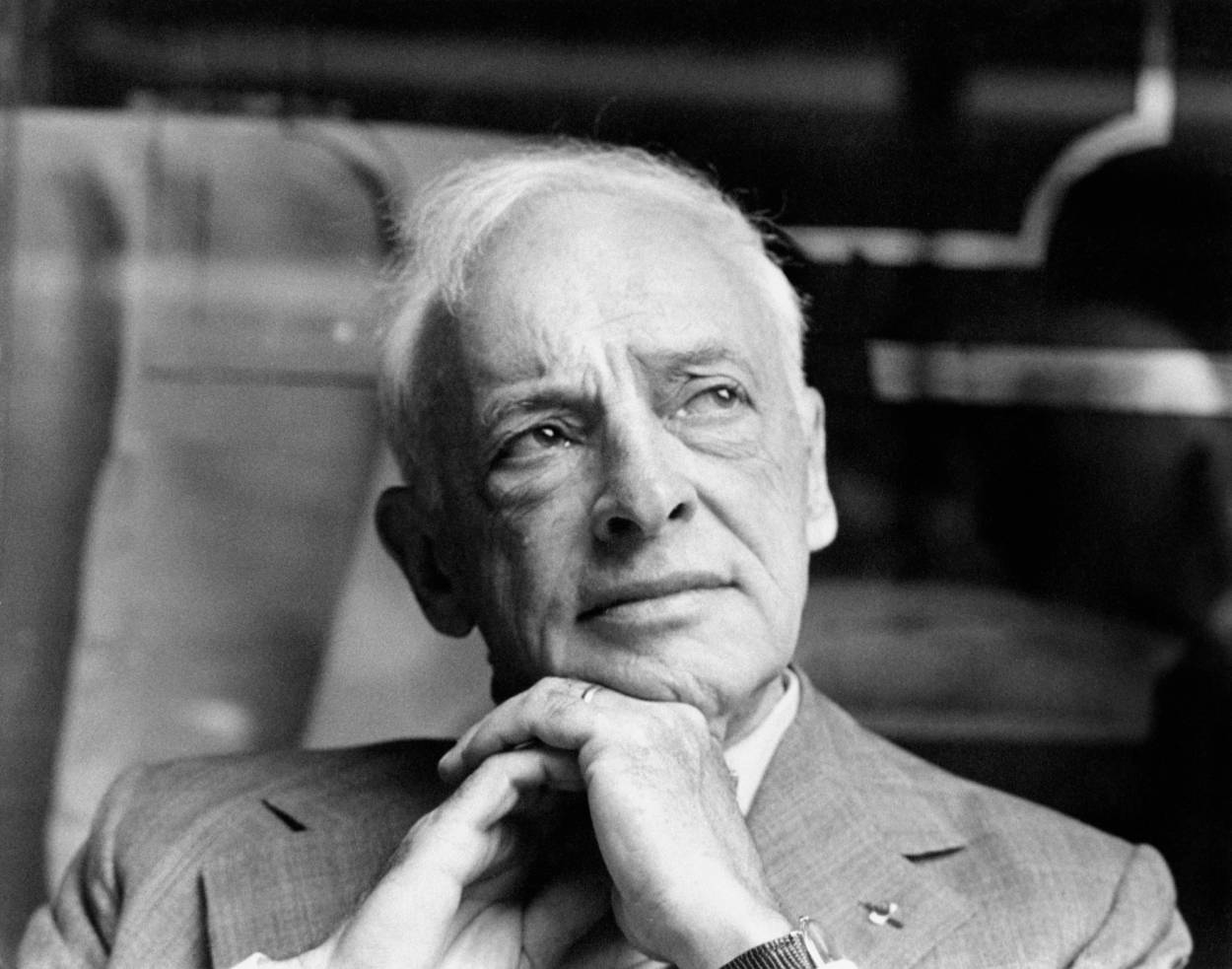

When the phone rings my agent throws me an apologetic shrug, meaning this is a call she’s been expecting and must take it. It’s rude to listen, so I don’t. I go to the window instead. Out there, this wildest of all cities throbs with the consciousness of its extravagant menace. It’s a hot day. A hundred-thousand air conditioners whir and rattle. After 15 minutes of deliberately not attending to what’s being discussed, I start to catch sentences that fire my curiosity. Let this one do the work of all the others. “Saul, you are at the height of your powers, no, you are not old, of course 70 is not old, and no one would take you for 70 anyway …”

Saul? Surely not the Saul? But there can be no doubt. Saul Bellow, as I live and breathe, Saul Bellow, born (as I will later take the trouble to confirm) June 10, 1915, here, in voice if not in body, in this very room, fretting about his 70th birthday and, by implication, the worth of his achievement. It is a valuable lesson. Neither accumulated years nor honors will ever make a writer feel secure.

I hadn’t read much contemporary American fiction in 1985. My Leavisite education encouraged me to be lazy. After the death of D.H. Lawrence in 1930, there were no novels I had to read. But in the course of reviewing my very first novel, the literary kingmaker Malcolm Bradbury claimed to discern in my prose something of the “bellow of wrath” (wink, wink) whereupon, to see what he meant—and whether it meant any more than that I was a Jew and those he was alluding to were Jews, that their protagonists made jokes and were libidinous and my protagonist made jokes and was libidinous—I sneak-read Portnoy’s Complaint, Humboldt’s Gift, and Herzog. Mr. Sammler’s Planet I had begun to read on the plane, but hadn’t got beyond the scene in which a Black pickpocket threatens the aging, half-blind Sammler by exposing his phallus to him, an experience I had so far managed to avoid in my three days in Manhattan.

Mr. Sammler’s Planet, it has to be said, was not an encouraging novel for a first-time visitor to New York. Dodge the dog waste and the urinating bums as you might, you would never be far from “sexual violence, knifepoint robberies, sluggings and murders,” and don’t expect the police to be of assistance. Mr. Sammler’s Planet is an erudite and fastidious meditation on the decline of liberal America. Plenty happens in the character sense as Sammler trudges the hellish city, encounters relatives and hangers-on, seducers and mountebanks, each vividly—not to say comically—illustrative of one aspect or another of modernity’s capitulation to mindlessness. But recollections of Sammler’s no less hellish past pepper the present. Victim and survivor of the Holocaust, Mr. Sammler killed, died, and was born again. In its own bleakly ironic way, as things slowly go from bad to worse, it is a redemptive novel.

I wish now I had seized the phone from my agent, wished Saul a happy birthday, and asked a question: “How come, Saul, you sandwiched (sandwiched by your painstaking standards) a novel as emotionally compacted and neurasthenic as Sammler (1969) between the frantic ebullience of Herzog (1964) and the sprawling exuberance of Humboldt (1975)? God knows, all three protagonists decry the times they live in, but Herzog and Humboldt are energized by all they deprecate and want a piece of it. Sammler, old and wounded, is a relic of another civilization. What made you choose so debilitated a man to guide us through this inferno?”

Not that Bellow’s high-wire vitality was always successful, even before Sammler. To my ear, the jaunty beginning of The Adventures of Augie March does not work. Nice try, but no, I don’t think you are going to “go at things as [you] have taught [yourself] free-style.” Very unfree and very much taught (if anything, over-taught) is what you sound from that first elegantly swiveled allusion to “Chicago, that somber city.” A pedant can easily drown in the demotic if he is not careful, and once he’s careful he’s not demotic.

Sammler’s nephew Gruner “had grown up in a hoodlum neighborhood and sometimes dropped into the hoodlum manner, speaking out of the corner of his mouth.” It wouldn’t be unfair to say that Bellow sometimes wrote out of the corner of his. That we laugh as often as we wince goes to show how good a mimic and self-mocker he could be. But for such comedy to be sustained, you need a grandly absurd and equivocal hero, and whatever heroics Sammler has pulled off in the nightmare past of Holocaust Europe, he doesn’t have the resources to go at Manhattan’s excesses free-style, or with the verve necessary to light up a novel.

In the course of riffing on the moral failure of those who should be inveighing against the debasement of the times, Sammler is indulged a feeble joke. What are the clergy doing to keep us upright? “Beating swords into ploughshares? No, rather converting dog collars into G-strings.” The Prophet Isaiah himself would have been funnier.

As a proxy prophet for Bellow, Sammler is on shaky ground. For the ventriloquism to have worked, for us to believe that he is powerfully troubled by the “sexual madness that was overwhelming the Western World”—a sexual madness embodied by the Black pickpocket’s pointing his “lizard-thick curving tube” at the old man—we have to set aside the far more terrible insanity Sammler endured in the extermination camps. Adam Kirsch put this well in an article for the New Republic in 2012.

At the corner of Broadway and 96th Street ... Sammler feels that the dismal scene seems to say “that the final truth about mankind was overwhelming and crushing”—but surely a man who was buried alive under the corpse of his wife would not need Broadway and 96th Street to enforce such a feeling.

Why does that Black pickpocket fascinate him? On what grounds, having seen him at work, does he “very much” want to see him again? Generally speaking, Sammler doesn’t have use for the “romance of the outlaw.” But “in evil as in art there was illumination,” and getting off the bus where he’d watched the pickpocket ply his trade, and with every intention of reporting him to the police, Sammler “nevertheless received from the crime the benefit of an enlarged vision.”

This explicit enunciation of the hold criminality exerts on the imagination of the artist—for that’s what Sammler becomes at this moment of absorption in the pickpocket’s art—brings to mind a similar passage in Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater. Calling on the gods of deceit, defeat, disappointment, shit, and “disastrous entanglement in everything,” Sabbath proclaims what is in effect Roth’s bad-boy artistic credo. “For a pure sense of being tumultuously alive, you can’t beat the nasty side of experience.”

Bellow, being more the visionary, grants the nasty side of experience the power to illuminate the mind. For Roth, it’s the power to excite the senses. Either way, you might say that only a buttoned-up, prim and proper Jew, of the sort both Roth and Bellow were, would need to self-justify.

The pagan dramatists didn’t have to explain away their engrossment in deicide and incest. They had no stern moralizer God to answer to. Jewish novelists, on the other hand, forever pretending to be the hoodlums they’re not, have to make some sort of an apology for their imposture before taking art where art exists to go.

In the matter of race, however, Mr. Sammler’s Planet throws down a tougher challenge. It isn’t only the repeated specificity of the pickpocket’s penis that’s problematic. It’s the whole “Jew brain, black cock” dichotomy, Sammler situating the cause of all the new laxity and license in the “Congo bush.” Congo bush! No matter that these words were written more than half a century ago, we avert our eyes as from a divine prohibition.

“I don’t think Bellow was a racist,” Studs Terkel said. “I think he was a bit more scared of black-skinned people than he should have been.” That’s a gallant distinction, which I don’t doubt explains much that passes for prejudice, whatever race or color its object. But in our time such fear is not allowable, either. Fear, too, is bigotry.

On the face of it, our age has grown a little too nice for both Roth and Bellow. And those recent encyclopedically candid biographies won’t do anything to improve their personal reputations. But as novelists, the future could be theirs. In showing a willingness to countenance what’s presently considered bad, their novels demonstrate the limits of what’s presently considered good.

I’ve never had the patience for the misogyny charge so often leveled at Philip Roth. Misogyny is not a literary sin. A novelist may dislike women as he may dislike Jews and still write sentences that light up the mind. And though Roth miscalculates aesthetically in supposing that, when a marriage goes to court, readers of either sex will always take the side of the husband, he’s right about the energizing tumult that a life as semen-soaked as Sabbath’s can unloose. Yes, it’s bloody, but isn’t it the function of art to draw blood?

Bellow’s appreciation of women fares no better with those for whom reading is a species of invigilation. But the closeness of his scrutiny of those women, like Sammler’s scrutiny of the Black thief, can be visionary, as illuminatingly witty in its minuteness as Dickens or Henry James, as voluminous and glowing as Rubens. The scenes in which Herzog observes his ex-wife Madeleine applying makeup, or genuflecting upon entering church, are masterpieces of comic and devotional observation.

It’s a cop-out to explain away the novel’s improprieties on the grounds that they are of another age. Any novel is what it is for all time, and we must take the good and the bad of it on the chin. And besides, if there is a pure exultancy in ugliness, where will we go to find it when all ugliness is expunged from discourse? If we truly believe that an enlarged vision is the artist’s reward for rummaging among the dross (I mean their own no less than society’s), we have no business setting limits to imaginative freedom.

In whose gift, once we muzzle artists, will be the visionary gleam?

Howard Jacobson is a novelist and critic in London. He is the author of, among other titles, J (shortlisted for the 2014 Booker Prize), Shylock Is My Name, Pussy, Live a Little, and The Finkler Question, which won the 2010 Man Booker Prize.