Letters From Multilingual Tel Aviv Show the Early Limits of Hebrew

How Jewish immigrants negotiated pressure to learn Western languages and maintain links between the Diaspora and Zion

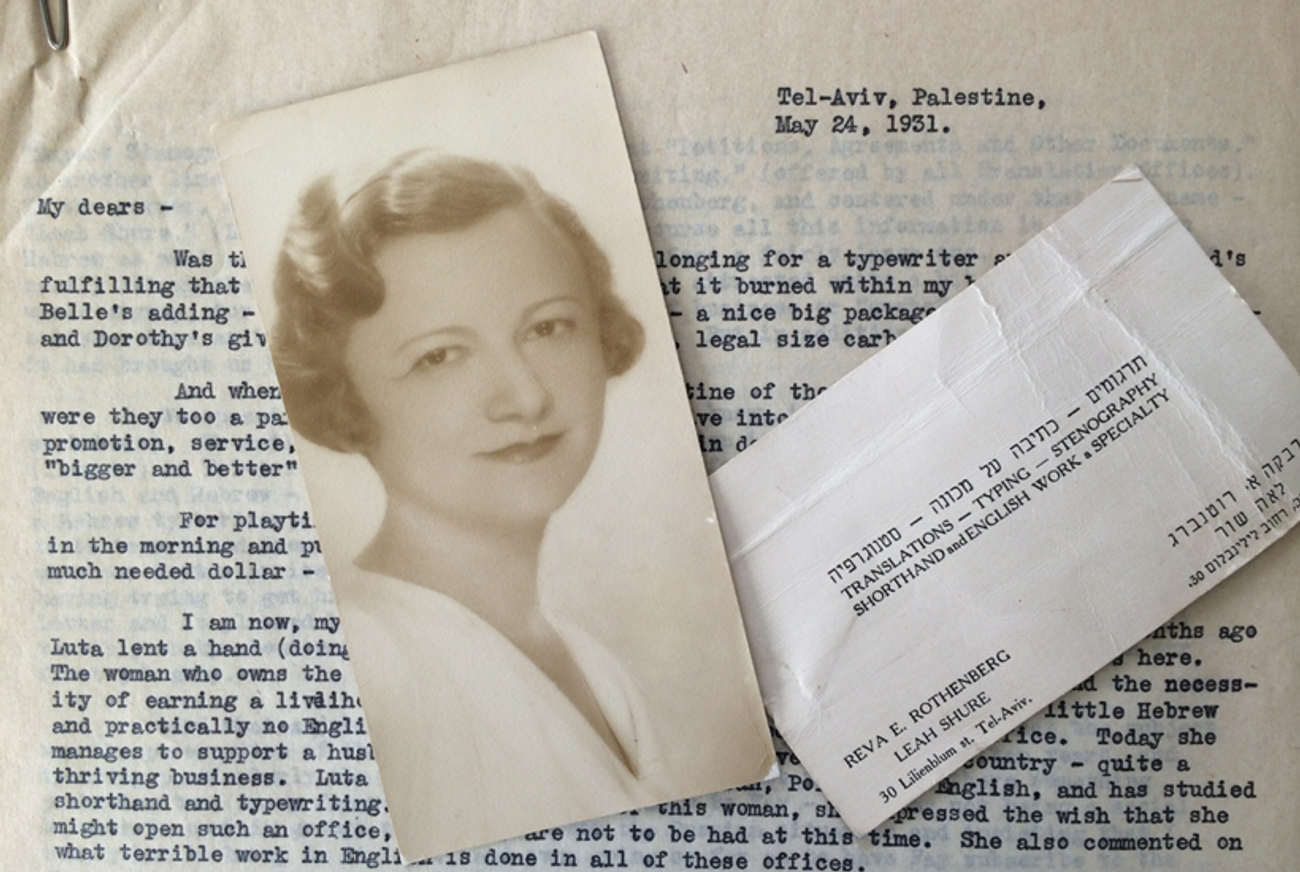

“I am now, my dears, the ‘English’ end of a Translation Office,” wrote Reva Rothenberg to her sisters in May 1931. She had moved to Tel Aviv the previous year from Illinois, joining her parents, who had already migrated to that emerging Jewish city in the Yishuv, as the Jewish community in Palestine under British mandatory rule was known. Once there, she found herself highly aware of the culture that surrounded her, and in particular the linguistic diversity that defined the place and in which she had become both personally and professionally involved. These language dynamics—present alongside and despite a public Zionist insistence on Hebrew use—tell us a great deal about the practical realities in a society under British rule, populated by Jewish immigrants speaking many languages and surrounded by Arabic-speaking locals.

Reva Rothenberg was my mother’s great aunt. Somehow, a set of her Tel Aviv correspondence made its way to my mother, who conveyed it to me in a large brown envelope this year—“You might be interested in this”—after my book on the history of language diversity in Palestine under the Mandate was already in press. Any number of Jewish families, in Israel or elsewhere, may have letters like these. Reva’s letters—and the fact that they were sitting in the desk drawer of my (third-generation American) mother, are a reminder that the experience of Palestine’s language dynamics touched nearly everyone who lived or traveled there.

But if the letters themselves illuminate a physical link between Diaspora and Zion, the contents of those letters suggest that this link persisted in language even for those who became rooted in the new homeland. They underline the social dynamics of the city as well as the ways in which this emerging “all-Hebrew” Jewish society remained economically and politically connected to the world of global commerce and the British-ruled, majority Arab context of Palestine itself.

Canadian writer A.M. Klein, upon his visit to Tel Aviv, marveled that insurance companies, sausage brands, dry cleaners, and ice-cream shops all had Hebrew names. Reva was similarly awed. On her first Saturday night in Tel Aviv, she recounts, she went to hear the noted Hebrew poet Hayim Nahman Bialik speak at the Oneg Shabbat event, a popular Hebrew cultural gathering on Saturdays. “I couldn’t understand anything,” she admitted (she knew only English and a bit of Yiddish), “but the Hebrew language is a musical one, and to me it seemed to blend well with the falling dusk.”

But falling in love with Hebrew, and indeed with the land itself, did not mean that Hebrew became her whole world.

***

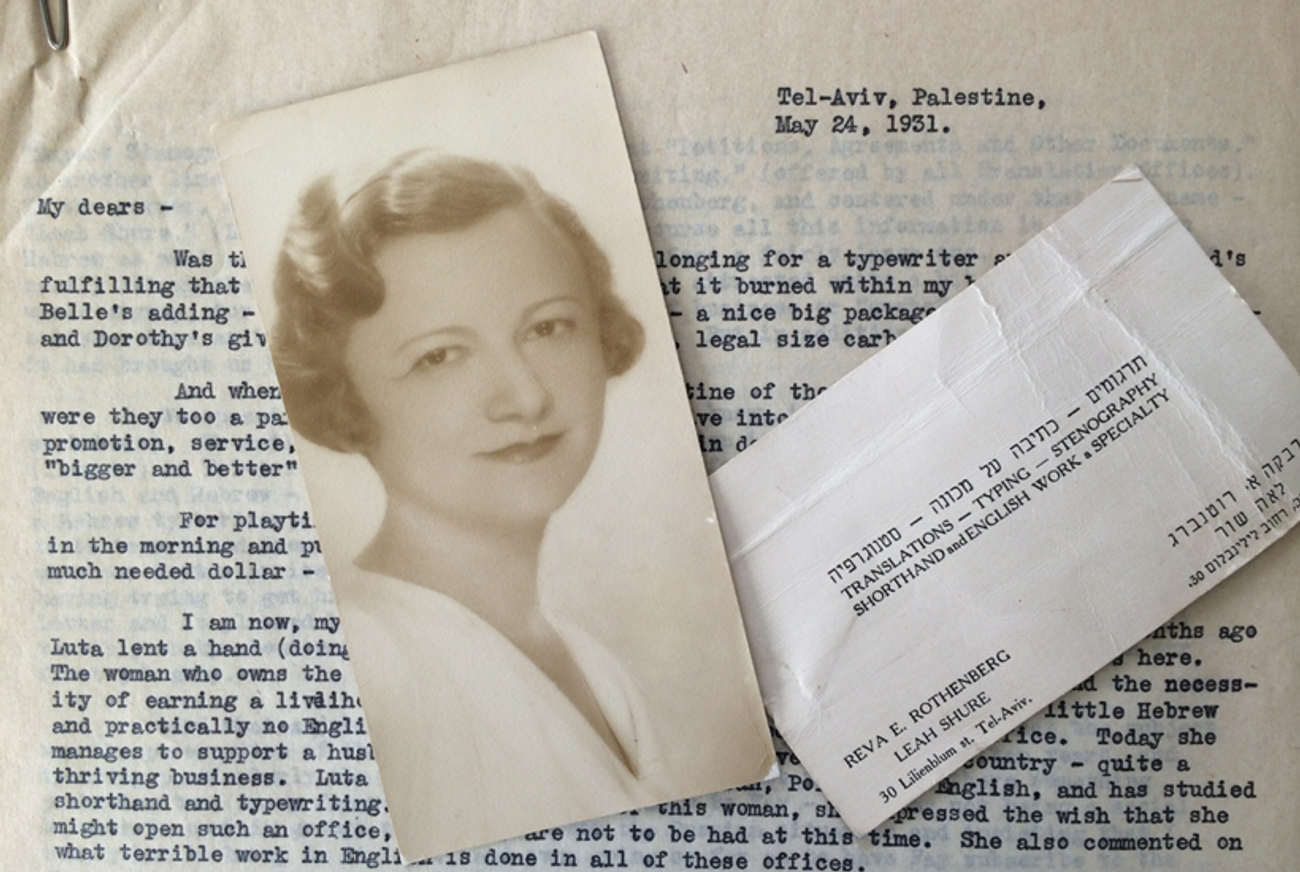

Jews in Tel Aviv needed access to people with European—and especially English—language skills in their communication with the British authorities. Languages other than Hebrew also facilitated international commercial transactions. In this economy, to the linguistically fluent went the spoils. Reva’s soon-to-be business partner, Luta, had started out in one of only a few translation offices in Tel Aviv, founded five years before, “on sheer nerve and the necessity of earning a livelihood somehow.” By 1931, Reva reported, Luta had “quite a thriving business,” enabled through her knowledge of German, Russian, Polish, and English, as well as shorthand and typewriting.

But even with those skills, Luta sensed that she needed a fluent English speaker, and she turned to Reva. “I,” Reva wrote, would “be the little godsend to this country and bring to it English, what an English.” Indeed, while English was frequently useful, the number of fluent English speakers in the Jewish community in Palestine was rather few. Reva and Luta set up shop near the main business section on Herzl Street, their workspace equipped—she tells—with a desk, an old Remington from a former tenant, six nice chairs, a plant stand with plants, a few pictures, calendars, and a map. “Our office is bright and cheerful and far more neat and pleasant and those of our competitors,” Reva gushed.

Advertising the place was no small feat as the printer, who knew no English, continually got the text of their sign wrong. Eventually, “after many trials and tribulations,” they had envelopes, signs, and letterhead advertising their knowledge of “Hebrew, ENGLISH (in caps with ‘a specialty’ underneath in parentheses), Arabic, German, French, Russian, Polish” as well as their ability to do “Expert Stenography,” petitions, agreements, and other documents, and give lessons in typewriting. Reva’s subsequent letters to America are printed on this very letterhead. It’s clear from this advertising that claiming to know lots of languages—even if they didn’t really know all of them—was an important marketing move.

One language not listed on the sign—Yiddish—brought in a good share of their business. Reva reports that they did “translations from Yiddish into Hebrew, contracts from Hebrew to English, Polish into English, etc.” Their system would work as follows: “Luta would put them literally into English and I would put them into actual English.” Knowing “actual English” seemed far more important than knowing Hebrew.

***

Off work, Reva found that she was embedded in a different kind of multilingual scene, a social environment made up of immigrants from a number of European cultural backgrounds. Reva felt deeply touched by being surrounded by this cacophony of Jews. “One cannot help but feel the brotherhood, the underlying oneness of spirit that exists here.” She wrote suggestively to her sisters of the sexual connections that emerged from within this brotherhood: “I had promised to give you a glimpse of the social life of an American girl here where the sun scorches—and the moon produces heat of another sort.” And she does not disappoint. But, interestingly, the story she tells is less one of moonstruck young love than of mutual non-comprehension.

Reva found herself frequently accosted on buses by older Jews, telling her in Yiddish that they had a boy for her, and she was regularly set up on dates by her parents’ friends. She quickly learned “that in Palestine, regardless of their vocation, from [age] 6 to 60, they all had but one avocation—‘shotchen’ or matchmaker.” The first candidate was the Polish-speaking Yitzchok, matched with her by a Polish lady. Reva and Yitzchok had no language in common, and so she found herself waiting for him on a Tuesday only to learn later that he thought their date was set for Thursday. Much offended, Reva wished to call things off, and the poor old matchmaker had to smooth things over, only for a similarly basic miscommunication to recur when the pair agreed to meet on “Zunabend,” a dialectical German term for Saturday, which Reva understood, wrongly, to mean Sunday night. This time, poor Yitzchok found himself stood up by Reva.

Dinner parties were stunningly multilingual affairs. “It is nothing to come into a home here,” she wrote, “and have your hostess speak to you in her slow, studied English, and then turn and converse rapidly to the guest at her right in Russian, switch to Polish for the benefit of her guest at her left, go into Hebrew for another, and then for good measure through in some French so no one will feel slighted.” The world of personal relations was bisected by language contact and language divides.

***

Reva, the American Jew in Palestine, lived in a wholly Jewish world, with its often comical language diversity and its language contacts with officials, business partners, and coworkers from around the world. We know from other historical documents that Jews bought produce from Palestinian Arab vendors, employed them to clean and do laundry, and, in more official letters, directed pro-Zionist propaganda at them, in print and through personal meetings. Yet despite the inclusion of “Arabic” on her business’s sign, Reva appears to exist in a world of European languages.

Reva’s perception of Arabs was also quite limited. On their way north to Ra’anana, on a rutted, unpaved road, Reva and her father encountered “many Arabs—some on donkeys so small one wondered how so tiny an animal could carry a man so big—some leading a string of camels—all of them so very dirty it would take a keen eye indeed to discern, beneath the rags and tatters and dirt, the handsome sheik the movies have accustomed us to picture.” Arabs to Reva were either the Oriental sheiks of Hollywood, or—as seemed to her—a degenerate shadow of this cinematic glory. “Here,” she reported to her sisters, “When you pass trees and well-kept land, you can be sure it belongs to the Jews. When you pass dirt and barrenness, it belongs to the Arabs.”

In Tel Aviv, she commented elsewhere, Arab carriages would crisscross the city on Friday nights, when Jewish transportation did not operate, “but no one”—at least in her social world—“would think of taking one.” Reva, though embedded in an Arabic speaking landscape, denigrated it as uncivilized and backward and seemed never to have interacted with it, suggesting a level of social separation that itself had important consequences for language.

“I can now understand and appreciate the story of the ‘Tower of Babel,’ ” Reva wrote in one of her letters, using the biblical metaphor of language mixing that many in her time—including Tel Aviv Mayor Meir Dizengoff—also employed to describe Tel Aviv and that I used as the title of my book. Reva would later move back to the United States, marry a son of the noted Sephardi Mendes family, and live in Los Angeles. Her reflections about Zionism, nationalistic as they sometimes were, did not ultimately reflect an ironclad commitment to stay in Palestine, nor did her emotional words about Hebrew prevent her from being in a nearly constant state of negotiation with other languages in both her professional and personal life.

In fact, the Babel that she found in Tel Aviv helped her understand “how the poor foreigner feels when he comes to the States.”

There were many others like her who did leave Palestine. But it would be wrong to assume that those who stayed had indeed cast off a multilingual diasporic experience in favor of Zionism’s promise—similar to promises of other ethnic nation-states—of a nation unified by one language. They, too, were constantly aware of, participated in, and reacted against the diversity around them, often with humor and irony, but also often with recognition that linguistic contact wasn’t just an inconvenient stage but an essential element of the Yishuv.

To this day, Israel remains committed to Hebrew as a national language, but its citizens continually negotiate pressures to learn Western languages (especially English), to speak or abandon immigrant mother tongues (Russian and Amharic stand out now), and to consider the status of Arabic, Arabic speakers, and Arabic language instruction. Reva’s letters are a piece of my family’s history; the story of language in the Yishuv—and not just the story of the triumph of Hebrew—is a part of the larger modern Jewish story.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liora R. Halperin is Assistant Professor of History and Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her book, Babel in Zion: Jews, Nationalism, and Language Diversity in Palestine, 1920-1948, was just published by Yale University Press.

Liora R. Halperin is Assistant Professor of History and Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her book, Babel in Zion: Jews, Nationalism, and Language Diversity in Palestine, 1920-1948, was just published by Yale University Press.