The Muslim World’s Intellectual Refuseniks Offer Enlightened Views on Islam and Israel

Egyptian playwright Ali Salem and others are marginalized at home and in the Western media, but they are political pioneers

When it comes to the Muslim world, Western opinion-makers seem to have a taste for what Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci called “organic intellectuals”—figures whose intellectual and political virtue flows from their rootedness in their native cultures. The West is allowed to admire its own native pantheon of free-thinking men and women who turned their backs on racism, anti-Semitism, and sexism and relied on the fiercest invective to scorch false beliefs and repressive practices. But Muslim intellectuals who condemn even the worst aspects of their own societies must be rootless cosmopolitans rather than genuine voices of Islam: It’s assumed that true voices of Islam must, to some degree, be racists, anti-Semites, and sexists.

This twisted general logic was seen most recently in the New York Times’ hiring the Egyptian novelist Alaa Al-Aswany as a regular op-ed columnist despite, or because of, his authentic belief in “a massive Zionist organization” that “rules America.” But perhaps the most famous instance was Ian Buruma’s celebration of the bigoted Muslim cleric Tariq Ramadan. Of course, Buruma admitted, Ramadan’s nudges toward reform were necessarily subtle, given the hidebound prejudices of the people he was addressing: He called, for example, for a “moratorium” on stoning women for “honor” offenses (i.e., having sex), rather than condemning the brutal practice altogether. Still, the fact that Ramadan’s tapes sold well on the Muslim street made him a model of reform-minded Muslim thinking worth drooling over. By contrast, Buruma suggested in other articles, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, an apostate from Islam, was alienated from her culture and therefore a fitting object of contempt—precisely because she was repulsed by misogyny and had been condemned to death by her accusers. Buruma’s strange defense of Ramadan and even stranger attack on Hirsi Ali were dissected by Paul Berman in his book The Flight of the Intellectuals: Berman argued that Hirsi Ali was just as representative of what happens in the Muslim world as Ramadan and just as entitled to speak about it; moreover, Buruma’s assumption that Hirsi Ali would be ignored by “real” Muslims was wildly condescending—those people, Buruma seemed to be saying, just aren’t ready for enlightenment.

Yet the marginalization of Muslim thinkers who embrace enlightenment values does not mean that they won’t win out in the end, as the example of the Cold War shows. Until the late 1970s, Soviet dissidents were similarly treated as doomed outliers, freaks and curiosities consigned to the dustbin of history. But it turned out that it was communism, not its critics, that landed in the dustbin. Perhaps the same will be true of Muslim theocracy; if so, it will be the Muslim refuseniks who will have paved the way—the Sakharovs of their place and time, largely ignored by the Western media, only to be acclaimed as prophets and heroes.

Irshad Manji, who calls herself a “Muslim refusenik,” has repeatedly condemned the common Arab description of Israel as an “apartheid state” or a fortress of “Zio-Nazism,” pointing out the many freedoms that Arabs enjoy there but not elsewhere in the Middle East. Nonie Darwish, whose father was an Egyptian fedayeen commander killed by Israel, runs a website called Arabs for Israel. And Hirsi Ali has been unsparing in her condemnation of Muslims who insist that Israel is really Arab land and that they have a religious duty to recover it. For these Muslim refuseniks (some of whom, like Hirsi Ali and Darwish, are actually ex-Muslims), rehabilitating the image of Israel goes hand in hand with a wider attack on repressive Islamic notions about women and family life. Others, like the ex-Islamist Ed Husain, focus on public policy (Husain has argued for full trade relations between Israel and the Arab world).

Most leading Muslim refuseniks live in the West. But in many ways the grandfather of the movement was Mahmoud Muhammad Taha, the Sudanese imam who campaigned for women’s rights and for recognition of Israel on the part of the Arab states—and who was hanged in 1985. While Taha’s fate suggests that going soft on Israel can be a risky idea for Muslim thinkers in the Middle East, there is also reason to believe that it is medieval bigotry and whacked-out conspiracy theories—not Israel—that will wind up in the dustbin of history, should the Muslim world ever embrace reform.

* * *

One of the defining characteristics of Muslim refuseniks is their determination to see Israel as a normal state, flawed like all others, but with an incontrovertible presence in the Middle East. Moreover, they also recognize Israel as a country where religion plays an influential role but has solid protections for the rights of women and religious minorities, democratic politics, and free speech. Rejecting the magical, theocratic image of the Jews and instead seeing them as normal and native to the Middle East could have enormous consequences for Muslim societies, since it would imply that other tribal and religious divisions—between Sunni and Shia, between Christian and Muslim, between the Muslim Brotherhood and its enemies—might come to be accepted too. Israel’s Jews are currently the least-vulnerable minority in the Middle East; recognizing that they are there to stay, and in their own state too, is a necessary realism, and realism is what ends wars.

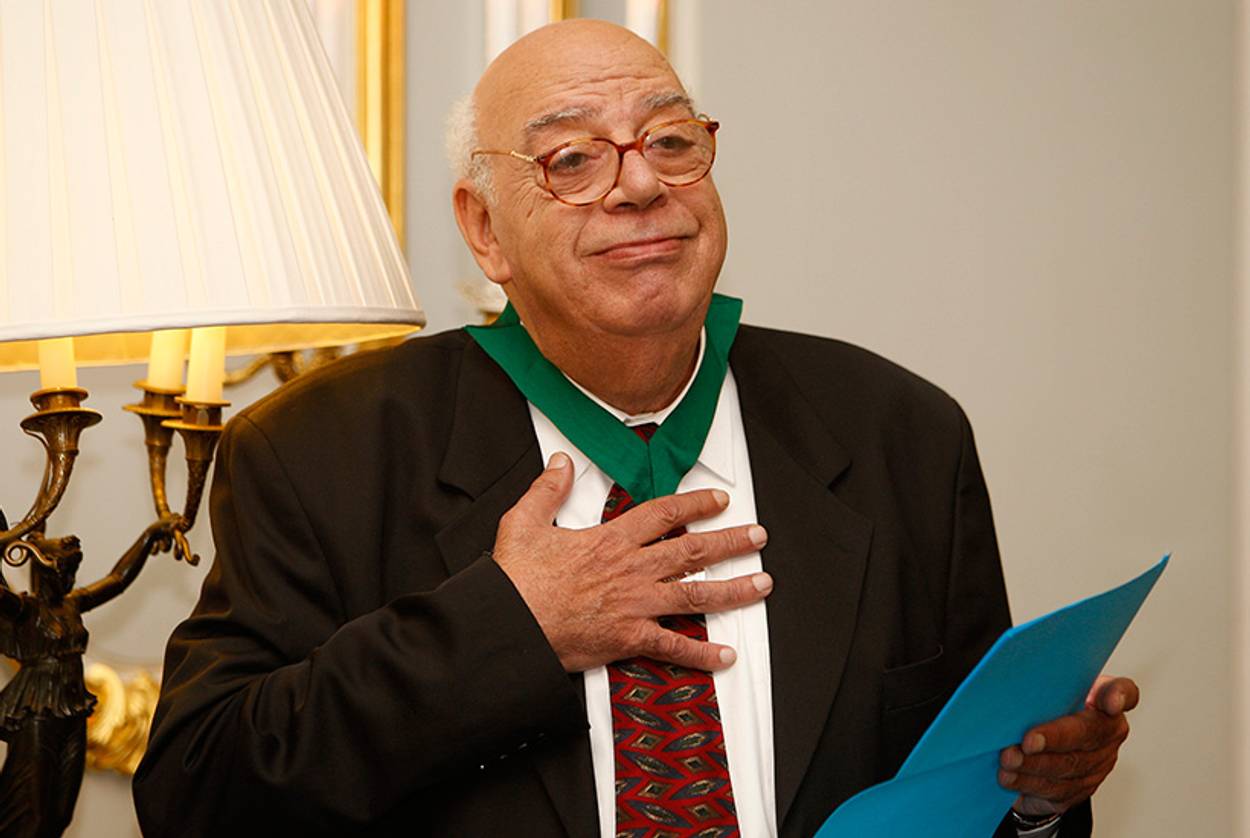

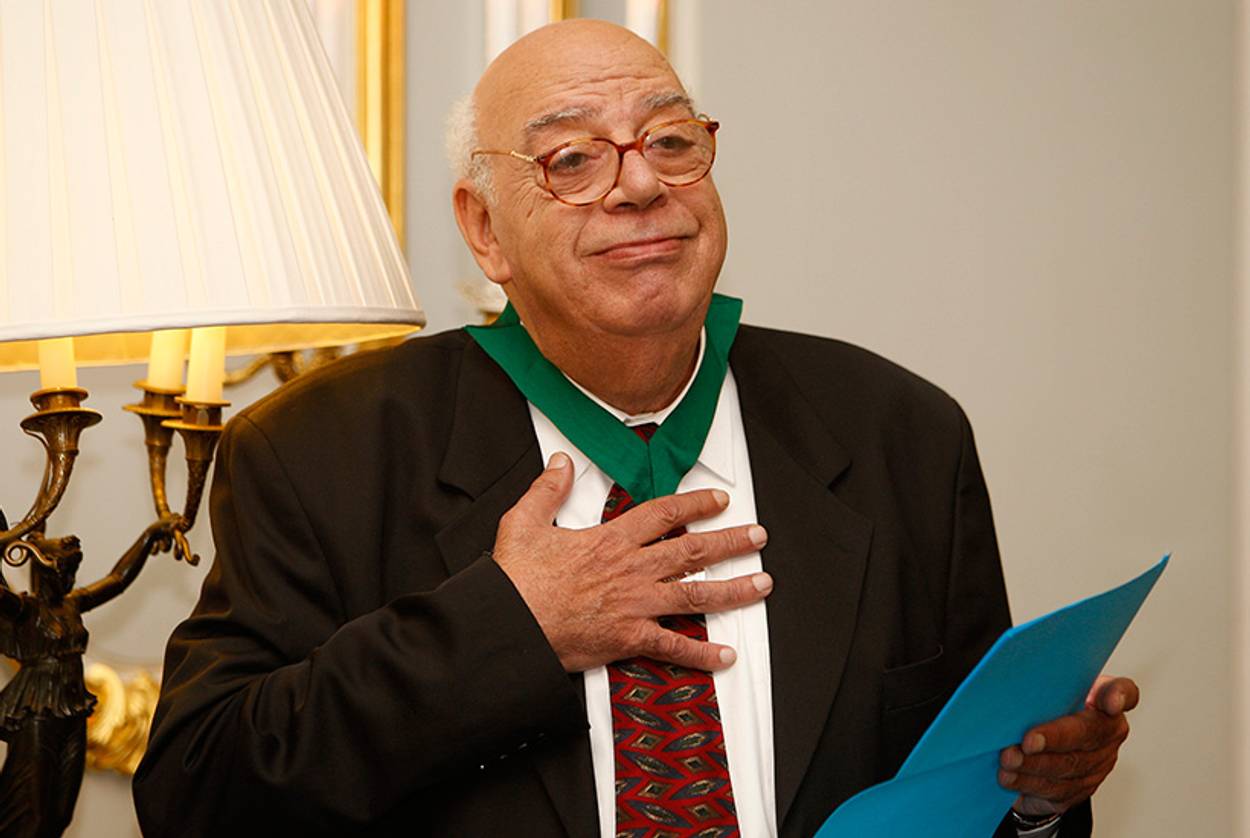

Which is how, in April 1994, Ali Salem, a portly, sardonic 47-year-old Egyptian playwright, found himself sweating as he approached the Rafah crossing into Israeli-occupied Gaza. In his sputtering, run-down Jeep, a green 1980 Niva (“the most durable legacy of the Soviet Union” in Egypt, Salem joked), he kept taking the wrong turn and missing the customs checkpoint. Something in him was preventing him from crossing over, from making what Salem called, in words familiar to so many Jews, his yetziat mitzrayim, his journey out of Egypt.

Salem conquered his resistance and made it to Israel that day in 1994. His book My Drive to Israel, the account of his journey, sold over 60,000 copies in Egypt, but it also led to considerable trouble for its author, especially after the book was translated into Hebrew in 1995. For an Egyptian writer to visit Israel, and to say, as Salem did, that he wanted to get to know the country better, to overcome his own hatred and fear, was an unthinkable act of disloyalty. Even worse, Salem showed sympathy for Egypt’s old enemy to the north; he admired Israeli society and he liked the Jews he met there.

Salem’s book flew in the face of the overwhelming consensus among Egyptians that the Camp David deal that Sadat courageously brokered and paid for with his life, must remain a mere glorified cease-fire with the eternal enemy, the Zionist state. Under Egyptian law, newspaper editors who have “normal” relations with Israel—professional friendships with Israeli journalists or public figures, for example—risk being fired. For a time Salem’s articles stopped appearing in newspapers, and no one dared to put on one of his plays. In 2001, he was thrown out of the Egyptian writers’ union. Joseph Braude, an American Middle East expert of Iraqi Jewish descent, told me, “Ali Salem is one of the bravest men I’ve ever met. He knew what he was in for when he set out to Israel, but chose to accept the consequences. Other Arabs who visit Israel now do so with less to fear because he blazed the trail.”

In My Drive to Israel Salem said many things guaranteed to provoke Egyptians, and they are just as provocative now, almost two decades later. He condemned the Arab-instigated wars of 1948 and 1967, and, mentioning with approval Yehuda Amichai’s remark, “Now we ought to learn Arabic,” he told Egyptians to learn Hebrew. His bond to the Mizrahi Jews he met in Israel especially was near-ecstatic; and he insisted as few commentators from Arab countries have ever done that the Jewish state is a permanent part of the Middle East. Though he was deeply troubled by the misery of the Palestinians, he did not allow this to poison his appreciation of Israel. Salem’s oversized thirst for life and his desire for peace shine through his little book.

My Drive to Israel is a very funny book as well as a courageous one. In his travels through Israel, Salem haggles with determination, explaining at one point that “the prices here [are] not appropriate for Egyptians.” He fantasizes that he is about to be seduced and betrayed by a beautiful blonde Mossad agent named Esther, as would happen if his trip were an Egyptian TV movie (alas, Esther never appears). Israelis express fascination with his archaic Jeep (“it won their admiration in a special way,” he says). Asked by a Jewish friend whether he knows the famous Israeli breakfast, a superabundant spread of cheeses, bread and fruit, Salem replies, “Unfortunately not. I only know the breakfast famous among intellectuals, which is coffee and cigarettes.”

Ari Roth of Washington’s Theater J collaborated with Salem on a staged version of My Drive to Israel and got to know him well. “He’s larger than life, a Rabelaisian figure,” Roth told me. “A big man, six foot three, a big, booming personality. He’s a man with a healthy appetite and a healthy ego; he’ll talk to anyone, bartenders, waitresses, cabdrivers, and he loves to hold court.” Nearly every day, shortly before noon, Salem appears at a table in one of Cairo’s finer hotels, to write and to talk with whoever comes by for a friendly chat and a taste of his sardonic wit.

“He leads with his Egyptian pride,” Roth told me about Salem, who, he said, believes that Egypt “can’t be stuck in a place of militancy in such a sophisticated world.” Roth reminded me that Salem’s brother “died in a tank in Sinai. He figured he could get further in a car than his brother could in a tank.”

* * *

A few Egyptians speak out like Ali Salem for closer ties to Israel, but they are very few and far between. The pressure to voice a damning reaction to Israel is strong. If you say there’s anything good or interesting about the country you risk being thought a traitor. One might think that, with the agonizing tumult in Egyptian society since the overthrow of Mubarak, Egyptians would be focused on their own fractured, violence-torn society, and that their internal divisions might overshadow the longstanding hatred of Israel. But this doesn’t seem to be the case. I asked Eric Trager, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and author of the New Republic piece that outed al-Aswany as a leading spokesman for the idea that Israel and America engineered Muslim Brotherhood rule to destroy Egypt, whether there are more Ali Salems now than there were 20 years ago. “Not at all,” Trager said. “Ali Salem is a laudable figure, but he is not remotely representative of the public mood.”

Braude, who is a frequent commentator on Al-Arabiya, one of the Middle East’s most popular television networks, acknowledges that there is a taboo against openly advocating normalization. But, he says, Egyptians send messages on the issue in a more covert way: for example, by making appreciative remarks about the Jewish role in Egyptian history. “Normalization in Arabic discourse is a long and subtle process,” Braude told me, “and the people who ‘perpetrate’ it strive for plausible deniability as a matter of self-preservation.”

Both men agree that while military and security cooperation between Israel and Egypt is just as strong under the new military rule as it ever was in the Mubarak years, but no one with any clout advocates a closer cultural relationship with Israel. Yet Ali Salem continues to hope. He has not changed his views since the withering of the promise of Oslo, the decline of the Israeli-Egyptian cold peace into a deep freeze under the Muslim Brotherhood, and the current uncertainty of military rule.

In February 2013, Ali Salem, now 77, was interviewed by Egypt’s Al-Ahram newspaper. Salem told the interviewer, a hard-line anti-Israeli, “You think that the only solution is to expel them from the land, but that’s not feasible—just as they have no prospect of expelling you from this land.” A few years earlier, in 2005, Salem was assailed on Egyptian television by critics who accused him of being an “Arab Zionist” and of “launder[ing] the reputation of the occupation” with his frequent trips to Israel. “What do you gain by going there?” he was asked. Salem responded calmly: “We prove to them that not all Egyptian intellectuals are against them, or deny their presence in the area. … We are tied to Israel by a peace treaty. The issue that remains is whether you recognize this treaty or not. … Egypt cannot sign a piece of paper and then say, ‘I am not responsible for this.’ ”

* * *

Salem thinks that true cultural dialogue between Israel and Egypt will happen in the long run. Yet there are a few children of Ali Salem in Egypt who are determined to reach out now and make a real connection with Israelis. One example is a young woman with green eyes, a welcoming smile, and a hijab: Hiba Hamdi Abu Sayyaf, who reports on Egypt for Israel’s Channel 10 (Arutz 10). Abu Sayyaf has never been to Israel, but she speaks perfect Hebrew. “The Muslim Brotherhood thinks I’m a traitor, an Israeli,” she told Channel 10 when asked whether she has been attacked for working with Israelis. “But my mother taught me not to be afraid of anyone.” Abu Sayyaf has said that one of her main motives is to show Israelis that they’re wrong about Egypt: Egyptians are diverse, and some even dare to appear on Israeli television.

Another of the lonely voices urging a conversation between Egyptians and Israelis is a 44-year-old teacher and blogger named Emile Bekhiet. Bekhiet is a Coptic Christian, but his blog features an allusion to a verse from the Hadith in which the Prophet Muhammad says to look for knowledge even if it is as far away as China. Bekhiet then writes, “Don’t look for knowledge in China, but rather in Israel! Learn from it what you don’t have. Learn how it deals with its citizens; learn from its armies not to point your weapons at your own people; learn from a nation that revived its people and its language.”

Bekhiet is a courageous man: He posts his email address and phone number on his blog, and when I asked him for an interview he eagerly agreed. “I know very few people who have the same views I do about Israel, maybe no more than five,” he wrote to me in an email. “I don’t hate Israel, and so I get a lot of insults and threats. I express my opinions on Israel very clearly on my blog and on Twitter, but, I regret to say, I mostly don’t mention them in conversation because I might be attacked, verbally or even physically. People are likely to have a violent reaction and start accusing me of treachery and being an Israeli spy.”

When I asked Bekhiet whether he knew any other Egyptian bloggers who, like him, had sympathetic views of Israel, he could think of only one: Maikel Nabil Sanad, also a Copt, who has spent time in jail for “insulting the military.” As an avowed atheist and a conscientious objector, Sanad is so disdained by the Egyptian public that his views on Israel are easily brushed aside or, more often, taken as further proof of his morally degraded character.

Obviously, Egypt has a long way to go before opinions friendly to Israel are taken seriously, seen as worth listening to rather than as evidence of the speaker’s craziness or corruption. If and when that happens, though, Ali Salem will be remembered as a pioneer who, in his rusty Russian Niva, helped forge the way.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Bellow’s People: How Saul Bellow Made Life Into Art. He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.