Some Childhood Memories of My Friend Danielle

Australia was as far from the horrors of Europe as she could get, and yet that wasn’t far enough

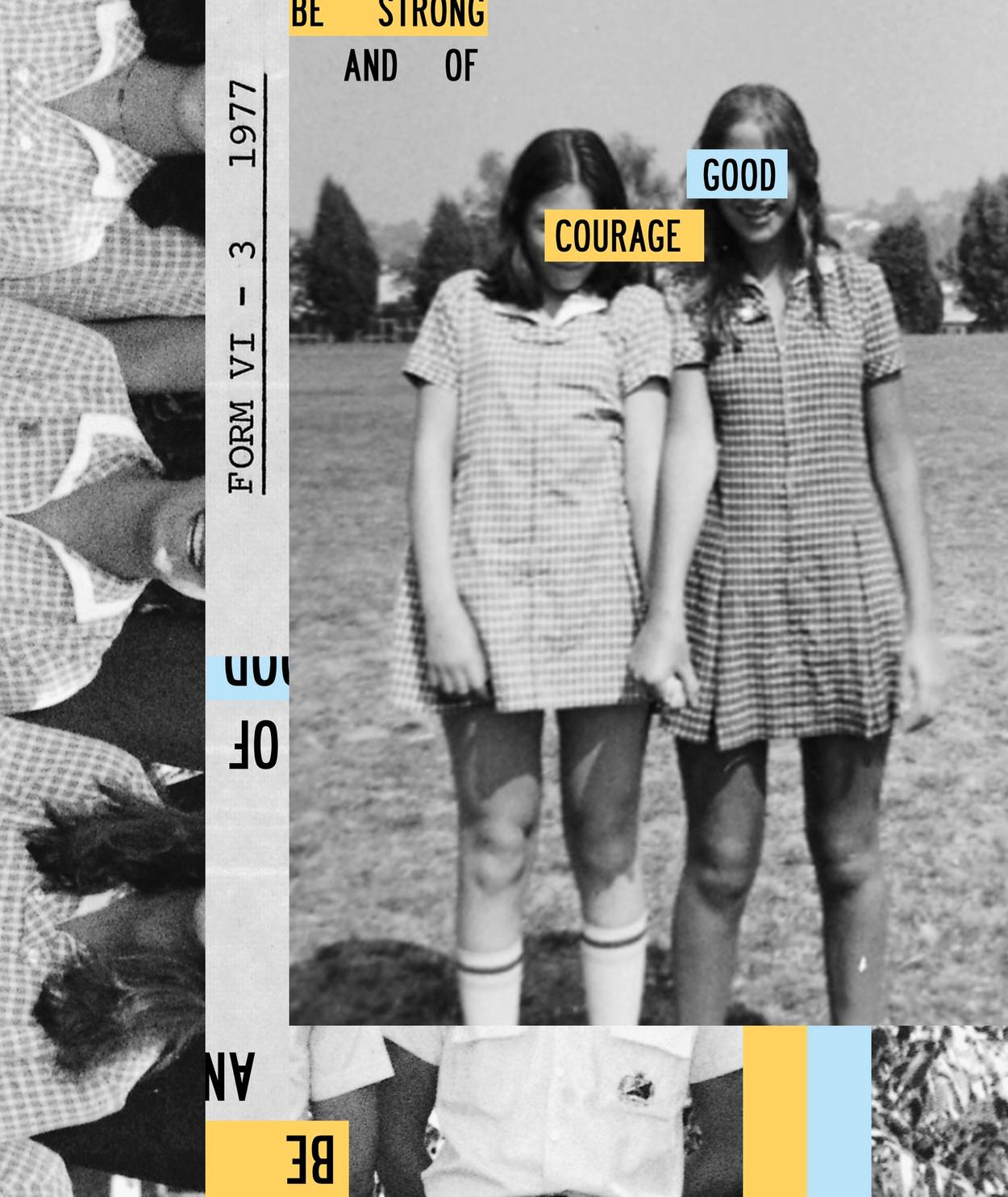

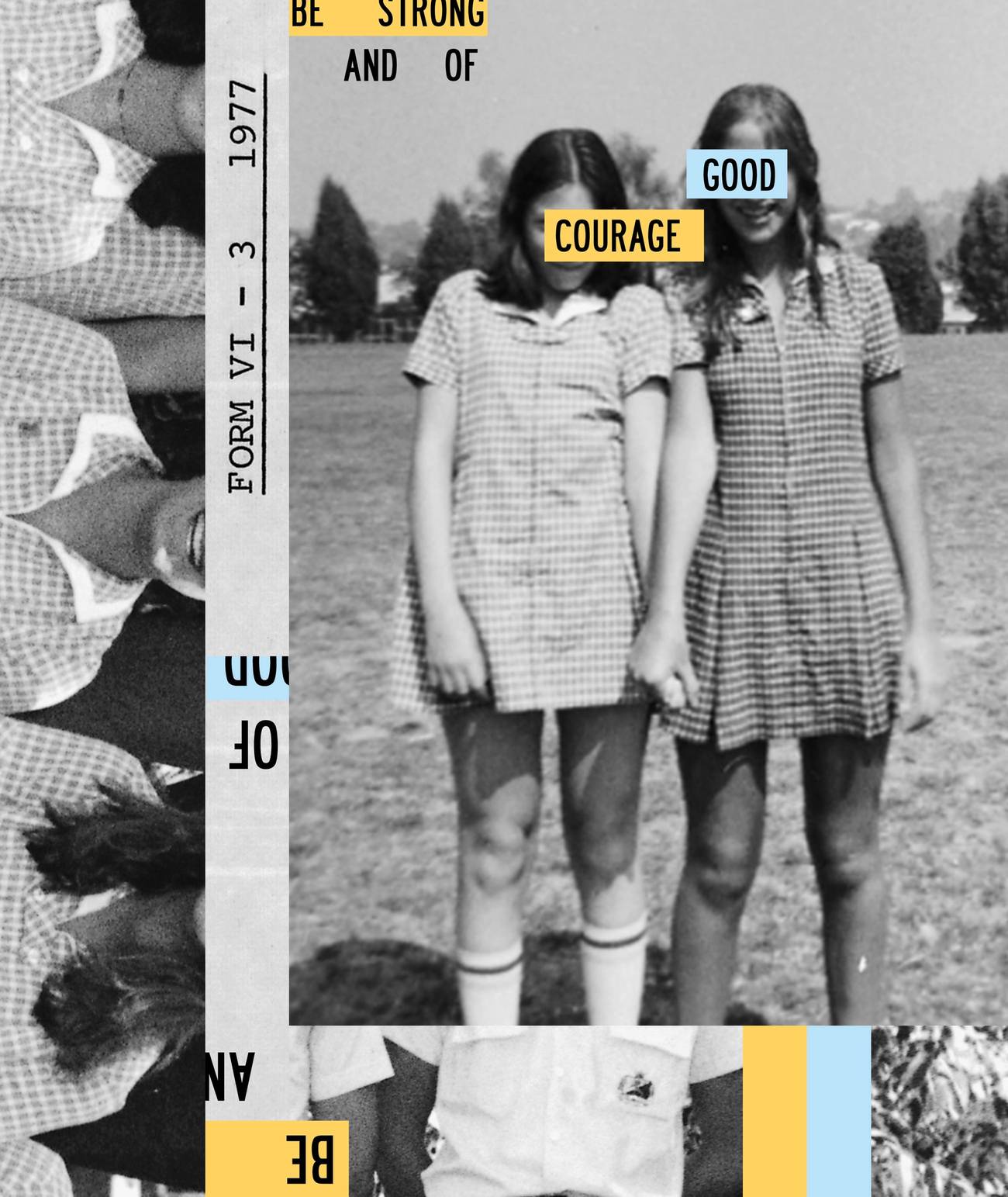

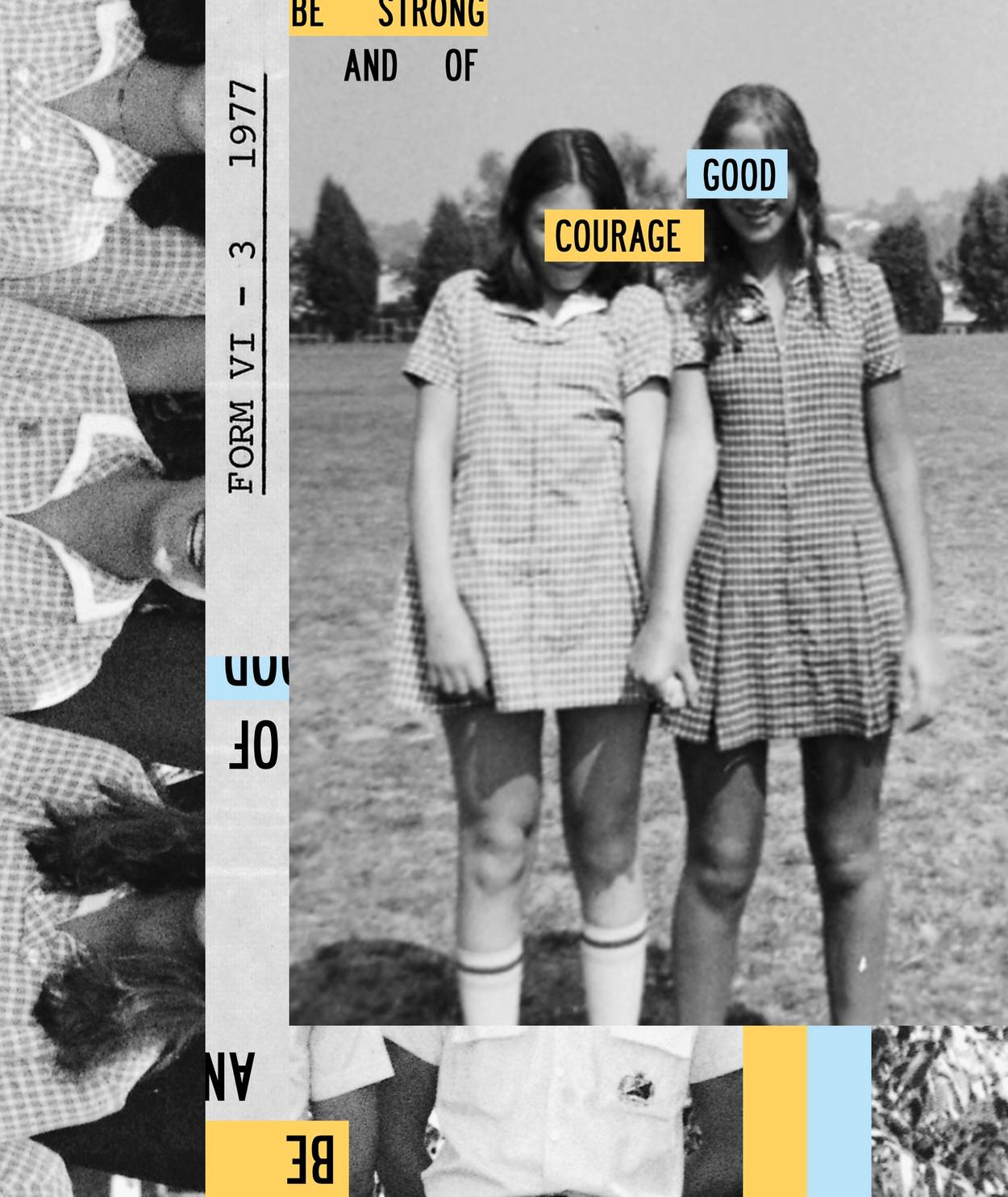

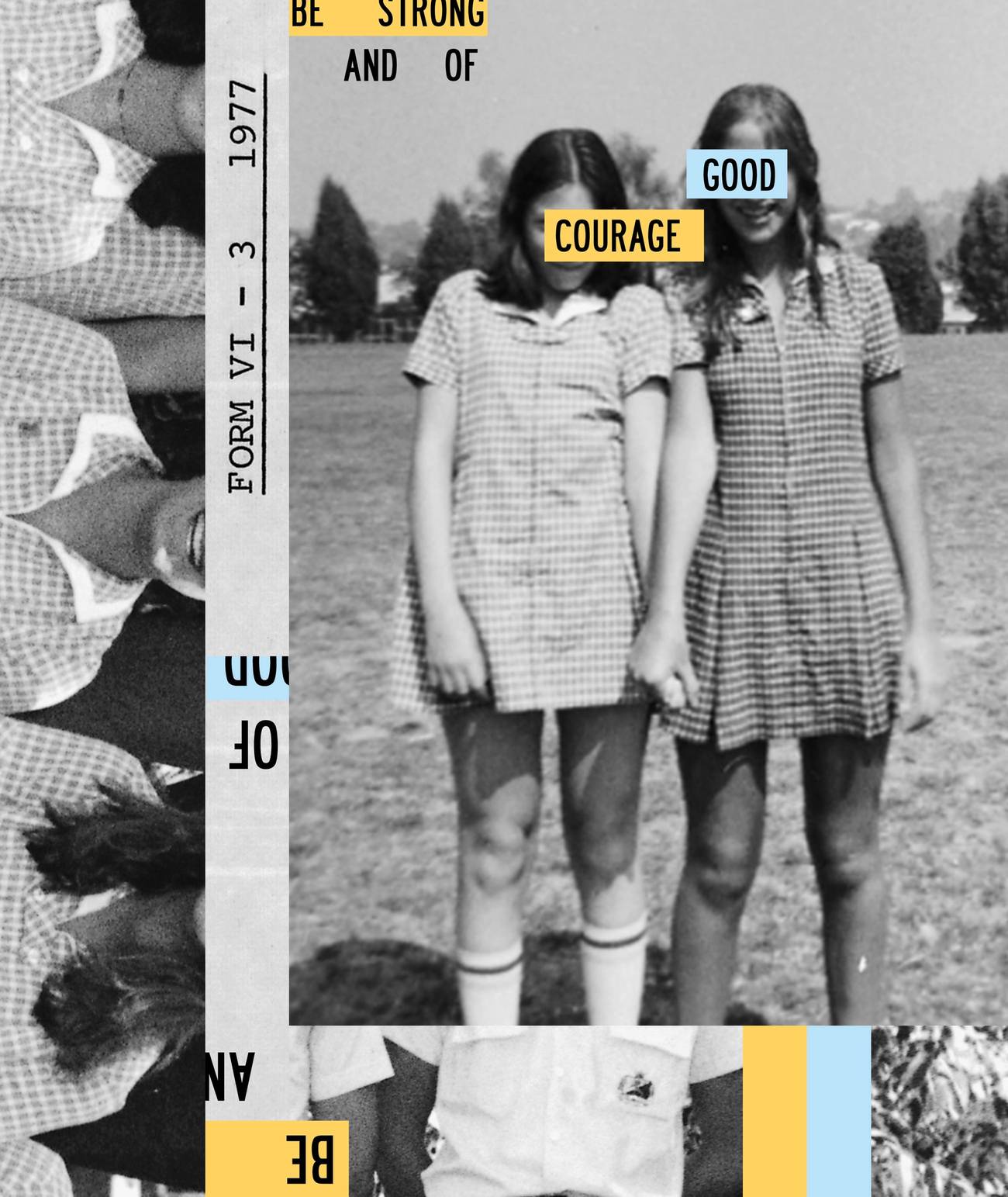

Danielle Gold and I became best friends our first day at the new high school, falling into each other, the way teenagers do. Our schoolteachers had heavy Eastern European accents—mostly Polish, though some Russian, Lithuanian, and Czech—as did the parents of most of my new friends. After the Australian public school, everything was strange, including the symbol emblazoned on our powder-blue satchels: a lion raised on its hind legs, front paws held high, with the Hebrew words Chazack Ve-Ametz and below, the English, Be strong and of good courage.

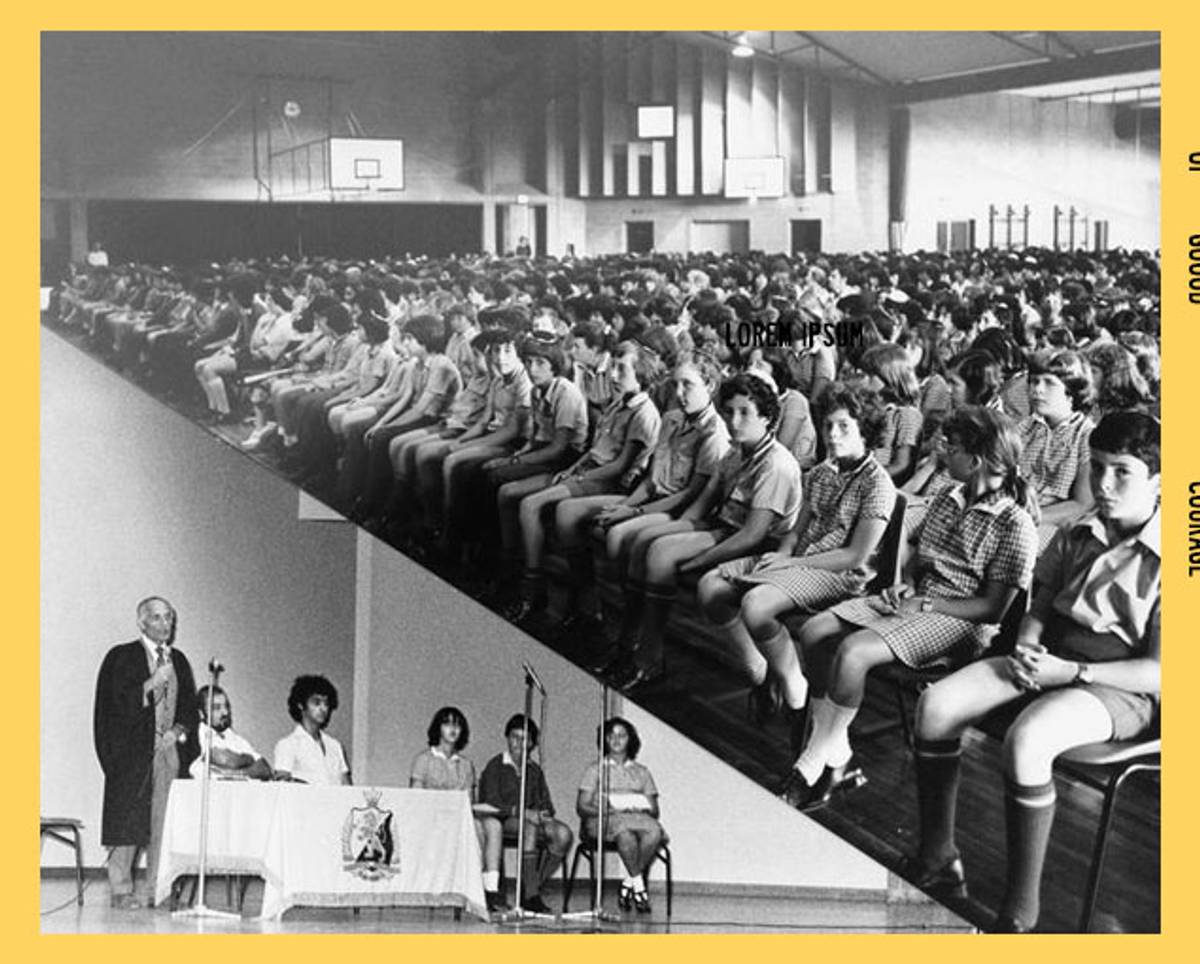

The motto held a special urgency because the school was founded in 1949, only 25 years earlier, by Holocaust-survivor refugees. The thickest accent of all belonged to our principal, Mr. Ranoschy, a diminutive man elegant in his thinness, whose intense gaze and baldness somehow went together, as if the burning in his eyes had incinerated his hair. He insisted on our pursuit of excellence, whether we wanted that or not. Our school had been entrusted with—encumbered with—the mission to rebuild a destroyed world here, in sunbaked Melbourne, the farthest habitable place on Earth from murderous Europe. Here, we were all phoenixes, rising from the pyre. Having immigrated with my parents from South Africa set me apart from my classmates, whose parents inspected their grades with a corrosive perfectionism that I could not understand.

At Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, on a youth tour Danielle and I took together at the end of 10th grade, it hit me: The emaciated faces in the photographs of liberated concentration camp victims were the faces of my friends’ parents; the skeletal bodies in huge piles, arms askew, open dead eyes and grimaces of suffering, were the murdered bodies of their grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins; for some, the small child corpses were their own siblings—their parents’ first families—thrown up against electrical wire fences for sport. One school friend’s mother had recognized herself in a photograph here, on the wall at Yad Vashem, a gaunt teenager in prison rags whose dark eyes held the awful knowledge she spent the rest of her life trying to strangle.

Danielle Gold was one of these second-generation kids. (To protect Danielle’s privacy, I’ve changed her name as well as those of her family members.) That day at Yad Vashem, I reached for her hand as we walked through those rooms; a moment later, I became aware that there was something cruel in my gesture—like throwing an imaginary buoy to someone struggling to stay afloat.

For survivors of genocide, there is no old country to remember with longing, warmth or hope: families, generations strong in their home country, stripped of citizenship, told they had no right to live. And since surviving at all was a statistical rarity, each of their stories was remarkable: tales of impossible near escapes, of being plucked by the fates from a multitude destined for death, often through extraordinary coincidence or confluence of precise, highly unlikely events. After the war was time spent in displacement camps, then uncertain, extended wanderings: closed doors and endless trials of one sort or another. I picture these malnourished young souls with haunted eyes—my friends’ parents as teenagers or young adults—arriving on boats to Australia, bewildered by this massive island at the far end of the Earth, the terra incognita with its swaths of desert and mint-honey eucalyptus, its blistering summers and mild winters devoid of snow, its lethal funnel-web spiders and sweet-looking kangaroos that could viciously punch and kick.

Perhaps it was no coincidence that there were so many American TV shows in the 1960s and ’70s that cleaved to metaphors of people stranded in bewildering and sometimes threatening worlds, confronted by unfathomable practices and circumstances as they scrambled to get a foothold and survive. America had its own Holocaust survivors and other war refugees, some of whom found their way to careers in Hollywood, alongside other American Jews attuned to the realities of their European Jewish brethren. I’m thinking of shows such as Lost in Space, which we avidly watched as children. Or Gilligan’s Island, My Favorite Martian, and a bit later, Mork & Mindy.

At Mount Scopus College, the atmosphere was giddy with possibility and hope; we were made to feel that with hard work, we could do anything. That if we were “strong and of good courage” we would grab every opportunity available in this open, friendly, egalitarian society. We were to be doctors and lawyers, accountants, psychologists, physical therapists, and teachers, all of us working toward an unshakable place of security and respect in this far-flung country that not a single Jewish refugee could, in their youth, have imagined they’d ever find themselves.

Our school had been entrusted with—encumbered with—the mission to rebuild a destroyed world here, in sunbaked Melbourne, the farthest habitable place on Earth from murderous Europe.

The giddiness had a double-edged feel—freedom tied to desperate escape. The glittering futures we pushed ourselves toward beckoned up ahead, but there was also something else; behind the school’s state-of-the art features—shiny, new science labs, expansive assembly hall, the neatly mown sports fields we called the ovals—something terrifying seemed to glower. A key moment in my own life was a school screening of the film Night and Fog, a documentary that included Nazi footage cataloguing Third Reich atrocities. I was sitting next to Danielle in the little school theater, and as images of corpses being bulldozed into pits flickered across the screen, she leaned in closely.

The film was a culmination of all the horrors I’d learned about in a school curriculum focused on a 2,000-year history of one set of murderous or expulsive terrors after the other—the list was endless, starting as far back as ancient Egypt. I remember one teacher, Mrs. Katzenellenboggen, who was remarkable for the heavy eyeliner she wore, which made her large eyes seem to pop right out of her face, and for her impressive, outdated, beehive hairstyle. I was repelled by the way she detailed the torture and execution of the first-century scholar, Rabbi Akiva, by the Romans, her accent an added layer of heaviness: And zen zey dragged ze metal combs viz zer razor-sharp teez sru ze flesh of his arms and legs.

We were exhorted time and again to remember, to never forget, though I intuited that my friends’ parents had made it their business to slam their memories shut in order to continue living.

I quickly took to spending weekends at Danielle’s house, which was different from the homes of my other friends in the area. There was something open and raw about the atmosphere, as if the sarcophagi of memory were not hermetically sealed. I felt the pull of stories vibrating with emotions too powerful to suppress.

Danielle’s parents adored me. They spoke of me as a second daughter and treated me as one, delighting in my conversational patter. We sat at the kitchen table for hours, eating and talking—and smoking, which for me was a glorious, transgressive freedom. If my parents knew I smoked, they’d have been apoplectic. Smoking was the ultimate taboo in our home, but Danielle’s father, Harry, thought it was just fine. He was a rakish fellow, short and trim, who wore a shmoozy nightclub-owner smile and always held a lit cigarette in his hand. Danielle would light up our first cigarettes while we were still lying in bed in the morning, two at once, passing one to me. She had a sardonic smile, and none of the hard-striving ambition-anxiety that vexed my other friends, whose families focused on education with an intensity that risked crossing over into fetish. Danielle was extremely smart and an excellent writer, but she didn’t do all that well in school. Her parents didn’t worry about any of that; her father worked in real estate, made a perfectly good living and didn’t seem to expect Danielle to go to college.

Danielle lived in a modest house that was often filled with her parents’ friends, fellow refugees who would sit in the kitchen chain smoking, drinking coffee and eating cakes from the Jewish European pastry shop on Acland Street, playing cards and talking loudly in Polish. All of them had been in concentration camps. Danielle’s parents were part of the sizable group who attended the annual Buchenwald Ball, where they’d sing the song they had, as slaves, been forced to sing while standing for hours in the brutal night cold, thinly dressed in prison garb. Danielle’s parents had miraculously survived years of horror in Auschwitz, then endured the long death march to Buchenwald, where they were liberated by the Americans at the end of the war. At the Buchenwald Ball, they would drink and dance late into the night, a brazen nose-thumbing to the universe. In Danielle’s home, the thick sound of the Polish language matched the laden atmosphere of an ever-replenishing fog of smoke and coffee fumes, the aroma of chocolate, cinnamon, and honey rising from plates of rugelach and tortes. And laughter—raucous, untrammeled: nothing like the restrained social behavior of the formal dinner parties my South African immigrant parents hosted for my father’s medical colleagues and other non-European friends.

One Sunday morning, I stumbled into the kitchen earlier than usual to find coffee to go with my first cigarette of the day. Mrs. Gold was sitting statue-still in front of the window in a kitchen chair, her back toward me. The room held a strange silence that raised goosebumps on my arms and made the air thin, as if the oxygen had been sucked away. She seemed unaware of my presence, though I was not taking care to be especially quiet. A fresh pot of coffee sat on the stove top and I helped myself, then leaned against the kitchen counter, sipping from my mug, gazing at Mrs. Gold’s frozen form. The hair at the back of her head was flattened from lying in bed, revealing the black and gray roots beneath the blond dye coating the robust curls I’d seen her set into place at night with large plastic rollers. Her early morning routine included slathering large amounts of Lancôme cream on her face and neck, something I’d marveled at, knowing how expensive Lancôme was and aware that the Golds were not people of means. In my own, more moneyed household, such a face cream would have been seen as a frivolous extravagance; and yet while Mrs. Gold was not indulgent in any other way, she applied the unguent with abandon, scooping up a great glob and smoothing it in until her face gleamed.

The silence was suddenly broken by the rise of Mrs. Gold’s heavily accented voice.

“It was so, so, so beautiful,” she said, her inflection guttural and unfamiliar, as if her voice were coming from some unrevealed place deep within.

She was speaking to me. She knew I was there.

“What was beautiful, Mrs. Gold?” I asked gently, my cigarette forgotten, burning slowly in the ashtray beside me on the kitchen counter.

“The snow. So beautiful. White snow, falling down from the sky.”

Her back still turned to me, she raised her arms high above her head, the way small children do. She craned her neck back to look up at the sky outside her window, a sky that showed the dawning Melbourne day, mild now, but holding the promise of intense, dry heat. Her arms still raised, she flickered the fingers of both hands and slowly brought them down, tracing the movement of snowflakes.

“Before the war, when I was a child, in Poland. Near the lake. I had a beautiful jacket with fur on the hood. My brothers and sisters would skate on that lake. I was too little. I couldn’t wait until I was older, until I could skate on the lake, too. I sat in my mother’s lap and the snow came down. So pure, so white. Everything white.”

Now, she was facing me, though I had no memory of her having turned the chair around. I know that for some minutes I had been gazing at her, taking in every detail of her face, which I can still see in my mind’s eye as if it is happening now and not 40-some years ago. I am looking into her broad face, the high, wide cheekbones that Danielle remarkably shared, remarkable since Danielle had been adopted at birth. At Auschwitz, Mrs. Gold had been a victim of Mengele’s medical experiments, which had left her infertile. Now, Mrs. Gold’s face is shiny with the Lancôme cream; silent tears stream from her bright eyes and her mouth spreads in a beatific smile, the smile of a small child. This child’s smile hangs uneasily on the lined, gleaming face of this woman in late middle age, existentially out of place in a way that triggers the queasy unease inspired by carnival clowns and children’s toys in horror movies. “You’ve no idea how beautiful the snow was,” she was saying through her tears. “So pure, so white.”

I myself had never actually seen snow, having grown up in temperate Melbourne, where people complain if the temperature drops to 50 degrees F. But I could see it then, just as she described, as if the roof of her house had opened up to reveal a Polish sky in the thick of winter. Both of us seemed to uncannily disappear; shadowy, inchoate figures reared up in my imagination. Like a mirage, I saw the child in the warm winter coat, the hood lined with fur, a child whose eyes were alight—naturally bright, not bright with haunting as Mrs. Gold’s had been moments before. An innocent smile illuminated the child’s face. The smile of a child who is loved and taken care of, who has known nothing but the tremulous, unfolding marvels of the world, who has seen only loving faces, felt only the strong, protective arms of her parents and older siblings, whose days are rippled with singing and laughter and a hundred satisfactions.

There was nothing unnatural about that smile. No, her smile was the most natural thing in the world. Large, fluffy snowflakes swirled down from a luminous white sky, frosting the pine trees, dusting the ice of the lake so that as the older children twirled and spun, flecks of snow danced up at their heels.

The Poland of Mrs. Gold’s childhood. So beautiful, before the war.

Toward the end of 11th grade, Danielle came to school one day clearly shaken. We met as usual at the buses and I could see that something was wrong, but she brushed me off in an uncharacteristic way, which left me worrying about her all morning as I sat bored through chemistry, Hebrew, math. I found her at lunchtime, grabbed her arm and ran with her to the back of the Skolnick oval, to the farthest edge, out of earshot of the other smokers.

We sat on the grass. I unwrapped my sandwich; Danielle left her lunch bag untouched. We lit up and she did her sharp, trademark inhalation, then let the smoke out in a slow, narrow stream. Her enormous green eyes, set with perfect symmetry in her wide face, were the color of worn sea glass; she had long eyelashes, which were always expertly coated with mascara. Her skin was creamy white and unblemished, her nose slim and elegant above a slightly unusual mouth whose upper lip had a little curl to it, the lower one jutting slightly forward, in line with a forward-thrust chin that signaled something of her stance toward life. She cast her gaze downward; tears slipped from her eyes.

“You know that bowl my dad keeps on his dresser,” she began.

I nodded. It was where Mr. Gold threw his spare change and single dollar bills for Danielle to grab if she needed money. Her parents were endlessly generous; there seemed to be no limits when it came to their daughter’s needs or wants. They lived without hierarchy, with none of the monarch-subject dynamics that marked my own home.

“I was going to get some change.”

Her tears were sliding, sliding down.

“It was lying there on the dresser, next to the dish.”

“What? What was on the dresser?”

Now she looked at me full on. “Do you know what the census is?”

I nodded. We’d discussed it at the dinner table—a civic responsibility, a symbol that we were an orderly society that took seriously the business of knowing its citizenry.

“I don’t know why my dad left the census there. I’ve never seen one before. They must have been careful, in the past.”

“Careful?”

“To hide it.”

Danielle then told me she had read through what her parents had marked on the census. In the section where you list children, she saw that in addition to her, three other children had been noted, their birth dates listed.

Born, February 12, 1938.

Born, January 26, 1940.

Born, August 3, 1941.

They all also carried a date of death—the same for each. December 3, 1941. There was no instruction to state the cause of death, but in the blank margin of the page, beside each of the repeated dates, Danielle’s father had written in his small, neat hand: Gassed to death at Auschwitz.

We were 17 and in our final year of high school. Danielle and I were walking down a busy shopping street, having taken off school again and charged up with a few tokes of hashish that turned Glenferrie Road into a boulevard taking us forward into a misty future, shimmering with unnamed dreams. Arm in arm, we stopped in front of a butcher’s shop and took stock of the offerings, laughing about what it meant to window-shop before a display of meat slabs ribboned with fat. I pointed to a giant pair of T-bone steaks and remarked that they’d make great snowshoes. This set us into a fit of stoned laughter, and we stumbled on down the street, flicking aside the disapproving glances of passersby.

We rounded a corner and Danielle came to a halt, radiating that sudden mood change I was familiar with, an instantaneous darkening. In front of us, a middle-aged man also stopped, smiling broadly, though with a mismatching metallic look in his eye.

“Hello, Danielle, darling,” he said, the heavy Polish accent turning the word to daalink.

Danielle was uncharacteristically stiff. She offered a few perfunctory words and we were on our way.

“What was that all about?” I asked.

“You don’t want to know,” she said, her tone matter-of-fact.

“Actually,” I said, “I do.”

She shrugged. “You know, stuff from the camps.”

“I don’t exactly know what stuff from the camps means.”

“He was in Auschwitz with my dad. He’s Connor’s father.”

Connor was an older boy from school—good-looking, popular, smart. He was dating a friend of ours named Lauren.

We were walking again, and Danielle picked up the pace.

“Why were you so curt?” I asked.

“We were on holiday at Mount Martha. Couple of years ago. Walking into town for ice cream with Uncle Moishe”—not actually Danielle’s uncle, her parents had no surviving blood relatives; Moishe had also been with her father in Auschwitz. “That man walked by. He came up to us, just like he did now. Kind of stopped in front of us, gave that smile. Moishe pushed him so hard, he fell to the ground. He kicked him in the stomach.”

She said all this in a flat voice, as if she were reporting on something mundane.

“What the hell?”

“Dad pulled him off. Uncle Moishe was red in the face. We walked away. I turned around and saw Connor’s dad getting up. He still had that smile on his face. Don’t you think he has the weirdest smile?”

“Wait. Moishe’s Lauren’s dad, right?”

Danielle nodded.

“Did you ask your dad what it was about?”

“He doesn’t like to talk about these things.”

“Did you ever find out?”

“Yeah, Uncle Moishe told me. Connor’s dad was a kapo.”

Of course, I’d heard about kapos. Prisoner functionaries, often chosen from the violent, criminal class rather than from the “religious prisoner” population, who were placed by the Nazis in a position of power over their fellow inmates and encouraged to be brutal.

“Oh,” I said.

“Yeah,” she said.

By the time we reached the Middle Eastern café we frequented, the effect of the hashish had worn off, so we ducked around the back to light up a joint. The smoke blew away the moody darkness; in the alley, arm in arm, we smiled at each other as we passed the joint back and forth, falling into that liquid space where we were one.

Inside the café, we sat over glasses of heavy Turkish coffee and played a dozen rounds of backgammon. Danielle was a master strategist and I didn’t often win. She looked at me dryly, her eyes perfectly deadpan, a little smile playing about her lips, threw the die then expertly moved her pieces without pausing to think or to count out the places, just a quick flick of each across the board. She won 15 games in a row.

I looked around, aware of a feeling of intense well-being and connection. Slinging the die from their faux-leather shaker across the board, I felt tethered to Danielle by the intimate looks that passed between us, the two of us stalwart together against drudgery and convention, our eyes trained on a distant horizon, far from the constraints of our respective homes—mine with its beauty and bursts of engagement and the confusing, unpredictable atmosphere, and Danielle’s with its fraught darkness curdled by insistent, heroic attempts to drown it out. Our truancy had a common goal: to swat away the life scripts being set down before us.

My heart breaks for Danielle, knowing the course that her noble, well-meaning, flouting of expectation took. I intuitively knew how to sidestep the rules while keeping my eye on the prize; Danielle held a match to it all and then found herself lost, wondering where and when the sense of possibility had slammed shut.

A few years ago, I heard that Lauren and Connor ended up getting married—Lauren, the daughter of the man who had accosted Connor’s father on the street, knowing him as a kapo from Auschwitz. Who knew what Lauren’s father was remembering the day he kicked Connor’s father in the stomach before being pulled off him by Danielle’s father? And who knew what was behind the kicked man’s strange smile, a doomed, lifeless half-moon, hanging below expressionless metallic eyes? I tried to imagine the wedding: the two fathers, one walking his daughter down the aisle to give her to the son of the other, whom he would always revile, pondering the haphazard destiny that had brought these two young people together in love.

I ended up moving to the United States and making my life there. Danielle and I lost touch.

Many years later, my mother told me she ran into Danielle at a little costume-jewelry shop on some side street, where Danielle was working behind the counter.

“She looked very thin, and weary,” my mother said. “When I asked her how she was doing, she looked so sad, it broke my heart. She said, ‘It’s been hard. Life didn’t work out as I expected.’”

“Did you get her number?” I asked. My own heart leapt at the thought of reestablishing contact with Danielle.

“I’m so sorry, I didn’t think to ask,” my mother said, and when I pressed her for information about the shop, she simply could not remember a thing about it—not the name, or the side street, or even what part of town she’d been in when she’d impulsively walked through the door.

On my next trip back to Australia, I was determined to track Danielle down. I made a few phone calls but then got caught up in the intensity of my family visit. Before I knew it, I found myself on the plane back to New York. Pulling away from the shore, I felt a spear of mortification that I had not followed through on my plan to find Danielle.

A few days later, my sister sent me a picture of the obituary she’d seen in The Jewish News announcing Danielle’s death. I never found out exactly how she died; everyone in that hyperconnected Jewish community seemed to have lost touch with her. I think of her death as a wafting away, rather than a passing, and wonder where she wafted off to, and if she was able, at the end of her life, to find some measure of peace. If I close my eyes, I see her in her school uniform, down at the back of the Skolnick oval, looking right into my face with her exquisite, expertly made-up eyes, reciting the birth dates of the children her parents silently mourned, all of them murdered on the same day. She takes a long draw on her cigarette and slowly releases a narrow, perfectly straight stream of smoke that hovers for an instant and then disperses into the air.

Shira Nayman is the author of four books of fiction: Awake in the Dark, The Listener, A Mind of Winter, and River. She is currently working on a memoir, from which this piece is adapted.