The Mysterious Bruriah Episode

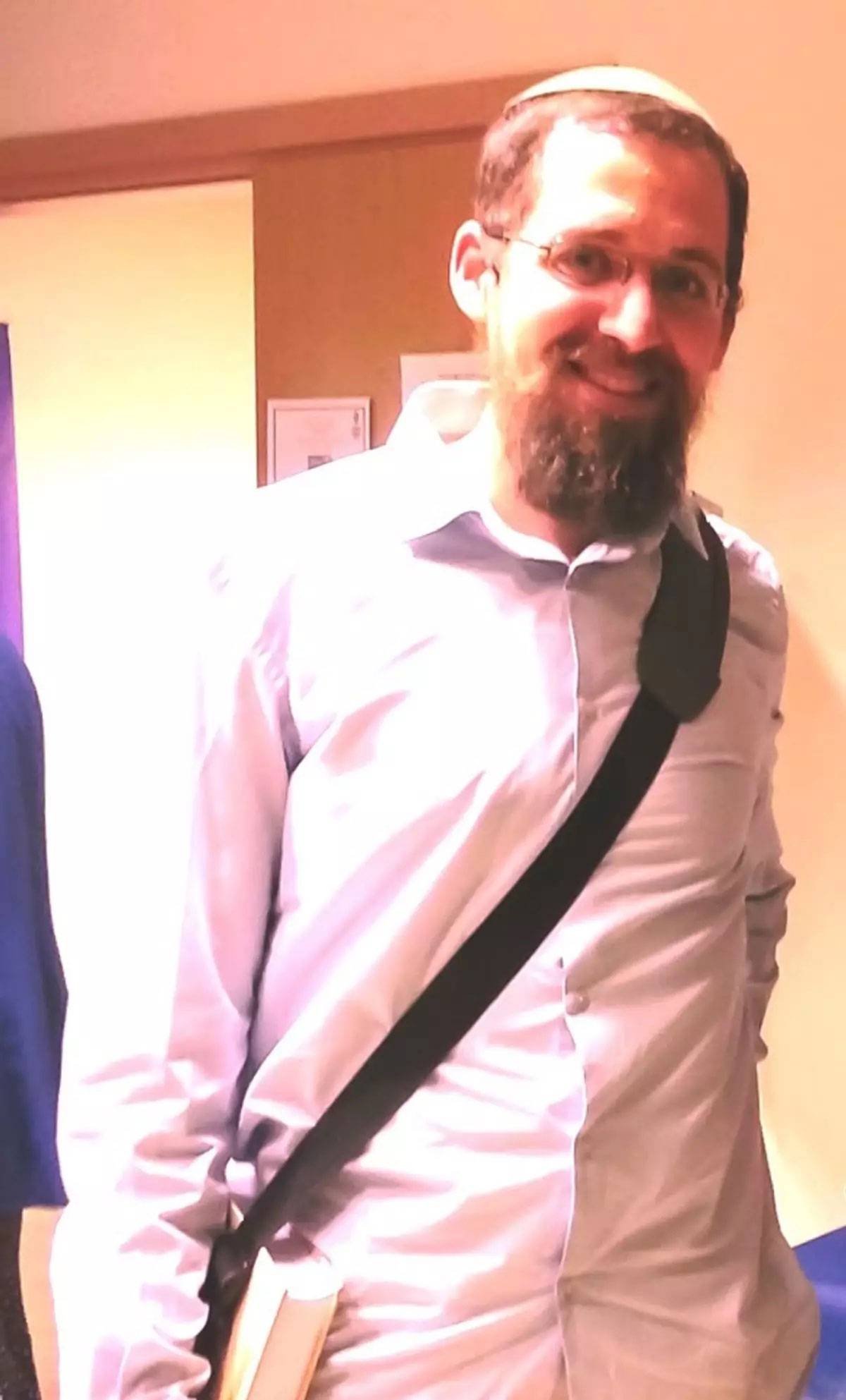

An excerpt from the work of Eitam Henkin, a brilliant doctoral student who was murdered by terrorists in front of his four young children

Eitam Henkin was a doctoral student at Tel Aviv University who also held American citizenship. Distinguished by his brilliant and original scholarship, an excerpt of which appears below, he was murdered in a Palestinian terrorist attack on Oct. 1, 2015, together with his wife, Na’ama, a graphic designer. The Henkins were driving past the town of Beit Furik when the attack occurred. The Henkins’ four children were in the van at the time of their parents’ killing. Five members of the terrorist cell, which was associated with Hamas, were indicted for murder, and for planning to kidnap the occupants of the car, including the children, a plan that was thwarted when Eitam Henkin tried to fight the attackers off.

In response to the killings, then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued a statement that read in part: “This is a difficult day for the State of Israel. We are witness to an especially heinous and shocking murder in which parents were murdered, leaving four young orphans. My heart is with the children, all of our hearts are with the children and the family. The killers knew that they were murdering a mother and father, the children were there.”

The relatives of Eitam and Na’ama Henkin brought a civil suit to a federal court in the United States against Iran and Syria for financing and arming the terrorist cell that committed the murders, and asked for $360 million in damages. In 2021, the court ruled in favor of the Henkin relatives. The ruling was the first time Iranian banks have been held liable for foreign terror activities that resulted in the killing of an American citizen.

Tablet hopes that the Biden administration will make sure that the court’s judgment is executed, in accordance with American law.

The first chapter of Avodah Zarah relates the events leading up to the pursuit of R. Meir by the Roman authorities, forcing him to flee to Babylonia: “He arose, fled, and came to Bavel.” The Talmud gives two explanations for his flight: either because of R. Meir’s entanglement with the authorities, as described beforehand, or because of the Bruriah Episode. What is the Bruriah Episode? The Talmud does not specify. The first to do so, hundreds of years later, was Rashi:

Once, she mocked the adage of the Sages that ‘women’s minds are easily swayed (lit. lightweight).’ He said to her, ‘By your life, you will come to agree with their words.’ And he commanded one of his disciples to seduce her into sin. He [the disciple] persisted for many days until she consented. And when she discovered the truth, she strangled herself, and R. Meir fled due to shame.

Rashi’s words received little attention over the course of successive generations, and when they did, they were referenced for their halakhic implications. However in our time, this has changed, with the Bruriah Episode receiving much attention in both the Torah and academic worlds. In light of the shift in the status of women in Jewish society and, more broadly, in the modern world at large, the rare figure of Bruriah—the lone woman to attain a status parallel to the Tanna’im—has received much attention, and even served as an educational model in the revolution of women’s Torah learningof the past several decades.

By contemporary standards, Bruriah is perceived without doubt as an exceptional role model, either as one of the Sages of the Oral Law whose words are quoted as halakhah, or as an exceptional woman Torah scholar,serving as an emblem of female success in Torah study. Either way, the strange story of the Bruriah Episode clouds this image, casting a heavy shadow on her behavior and the way she ended her life. It is therefore no surprise that the Torah world today attempts to soften the ‘Bruriah Episode’ for educational purposes, explaining it in a manner which fits what is known about R. Meir and Bruriah from all other Talmudic references. Religious feminists have similarly sought to negate the negative implications of the episode that are liable to be associated with women’s learning.

Before dealing with the Bruriah Episode itself, I wish to address several hypotheses, problematic both factually and methodologically, that have been advanced by feminist academics regarding the source and purpose of the story. It is widely claimed that the Sages used this story to delegitimize women’s Torah study and Bruriah’s exceptional accomplishments in this area. Were this true, we would have found the Bruriah Episode in the Talmud itself or in a Midrash of the Sages, and not in Rashi’s commentary alone. Not merely is this not the case, but precisely the reverse, the Sages often praise Bruriah and learn from her behavior. Over 200 years ago, the Ḥida raised the possibility that “from what occurred to Bruriah in the first chapter of Avoda Zara, the Sages conceded to the position of Rabbi Eliezer” who forbade the teaching of Torah to women—and immediately rejected such speculation, because we have no discernible proof that the Sages concluded this from the story or saw it as a representative episode: “From that which happened once to Bruriah, we are not permitted to extrapolate a halakhic precedent, so long as we haven’t seen this in [the words of] the Sages.”

Another claim is that Rashi himself invented the Bruriah Episode, constructing a hybrid of motifs in Talmudic literature, in order to establish that Bruriah’s end bears out the ruinous path on which she set out.It goes without saying that anyone versed in Rashi’s methodology and commentaries knows that this cannot be true. A brief quote from Rashi himself will suffice: “It is hard for me to say thus, as I have never heard this tradition.”

Despite our dismissal of the aforementioned claims, the reliability of the Bruriah Episode is worthy of clarification. Rashi’s source is unknown to us. The story does not appear anywhere in Talmudic literature, it is not mentioned in Ge’onic writings, nor do we find even a single mention of it in the period of the Rishonim, except for Rashi (and, in his wake, Menorat HaMa’or and Maharil, as we shall presently see). The story is singular and improbable, casting two exceptional Talmudic figures in a most problematic light.

From a human perspective, the story presents an extreme picture: Is it logical that because of a single instance of mockery (“one time”) of the Sages by Bruriah, Rabbi Meir would place her in a position to be seduced by another man? This is not the behavior of a level-headed man, certainly not one of the greatest Tanna’im. The description also does not fit with Rabbi Meir’s own activities in promoting shalom bayit, marital harmony, and it contradicts what we know about the exemplary relationship that Rabbi Meir and Bruriah had. Similarly, the episode is problematic halakhically: How could Rabbi Meir allow his disciple to seduce a woman into adultery, a sin for which both the man and woman are obligated to give up their lives before violating? This doubly confounding problem was addressed by Rabbi Israel Lifshitz, the Tiferet Yisrael:

Because [R. Meir] knew that he [the student] was God-fearing and would not actually commit the sin, even after she acquiesced, as she did. Heaven forbid that R. Meir would cause her to sin. Such is my humble opinion.

In other words, the story does not refer to actual adultery—lest one think that Rabbi Meir would instruct his student to commit adultery with a married woman—but with tempting and seducing alone. However, this answer of Tiferet Yisrael raises new questions: How could R. Meir rely upon his student not to sin, after all, “There is no guardian against sexual sin.” In fact, the Talmud in Kiddushin relates that R. Meir himself nearly succumbed to the temptation of Satan, who appeared before him as a woman. Besides, the student would certainly have sinful thoughts, themselves prohibited, so how could R. Meir allow that? Ben Ish Ḥai, Rabbi Yosef Ḥayim of Baghdad, asks this question:

An even stronger question on R. Meir Ba’al HaNes: How did he permit his student to perform this act of seduction without concern that the student would think improper thoughts at the time he carried out his seductive conversations with her?

And he answers:

In my humble opinion, this student was a eunuch, and had no sinful thoughts or desires. And she was unaware, because there are natural eunuchs from birth who are not recognizable from without, either in their features or facial hair.

In other words, according to Ben Ish Ḥai, R. Meir sent on this mission a student who had no chance of sinful thoughts, and certainly no chance of the sin itself. This answer, however, has no foundation in Rashi’s words. Moreover, even according to the explanations of Tiferet Yisrael and Ben Ish Ḥai, it is almost certain that the student would have needed to violate the prohibitions against secluding oneself with a married woman, itself a Torah violation (according to most opinions), and might even be considered avizaraihu d’gilui arayot, acts leading to adultery, for which one is obligated to give up one’s life to avoid. Besides, the questions regarding R. Meir’s behavior arise not only as regards his disciple, but also Bruriah herself—as he seemingly transgressed several biblical prohibitions regarding his wife, including placing a stumbling block before her and causing her pain. My father [R. Y. Henkin] asked thus regarding the answer of Ben Ish Ḥai:

It is difficult, in my humble opinion. Is the problem only vis-à-vis the disciple? No lesser a question begs, how R. Meir could have allowed himself to sin against his wife, tempting her thus, and transgressing, ‘Do not put a stumbling block before the blind!’

Another equally disturbing question can be directed at Bruriah herself: How could such a supremely learned woman permit herself to commit suicide?Against these questions, my father surmised that the Bruriah story is not from the Sages but rather a folk tale:

Therefore the story is not reasonable, in my humble opinion. … This story is not found in Talmudic literature and its source is unknown, and the other Rishonim do not mention it. Perhaps it is rooted in some tale or source into which Bruriah’s name became inserted. We have no complaint with Rashi, as he simply recorded what he heard. And even though we cannot compare Rashi with the Aḥaronim, we see something similar in Tiferet Yisrael at the end of Mishnah Kiddushin (note 67) where he relates a strange story about Moses, but since then, it has become clear that the story’s source is a popular gentile tale about Aristotle.

This solution is also undeniably problematic. It is difficult to assert that Rashi—the greatest Talmudic interpreter—naively inserted a story that he heard from questionable sources, especially a story so unusual and illogical. However, the suggestion that the source of the story is not in rabbinic literature is reasonable.

On the basis of this conclusion, I wish to suggest a different answer to the source of the Bruriah Episode. As my father stated, the story indeed reached us via questionable sources. However, in my humble opinion, it is not Rashi who wrote it down, but someone else whose words made their way into Rashi’s commentary.

To understand how this came about, we need recourse to the manner in which manuscripts were handled in the Middle Ages. Until the advent of the printing press (and for some time afterwards), a person who wanted to note comments and corrections on the content of a manuscript, would not normally do so on a separate piece of parchment, which was an expensive commodity. Instead, he would write notes in the margins and, sometimes, if space was unavailable, between the lines of text itself. So it is not surprising that when a scribe copied the manuscript, he could easily confuse the main body of the text with the comments. We know of many examples of paragraphs and sentences that entered in this fashion into various commentaries, and even into the Talmud itself. Ge’onic responsa already address several places in the Talmud where Savora’im had written full sentences in the margins, and the scribe mistakenly brought the notes into the main body of the Talmudic text.

Rashi himself testifies in several places that a sentence in the Talmud that he had before him came from a mistaken student who wrote a marginal comment: “This version written in the books is flawed, written by commentators who were not well-versed in the tradition, and placed an incorrect explanation within the text.” Likewise, “this text in elu hein halokin is the correct version, but a mistaken student who had difficulty understanding wrote it down [here] in his copy.”

Is it plausible that an insertion of this sort occurred in the Rashi we are discussing? Rashi’s writings were in the hands of the greatest of the Tosafists (foremost among them, Rashi’s own grandchildren) for many years. They explained and often argued with Rashi across the entire Talmud. When they felt Rashi’s comments were questionable, they never shied away from saying so. It would be only natural to find some question on their part regarding the Bruriah Episode, seeing how the episode is rife with questions from beginning to end. Compounding this is the fact that Rashi’s commentary is the first and only source for the story.

However, the Bruriah Episode is not mentioned at all, or even hinted at, in all the compilations and commentaries of the Tosafists! In fact, there is no reason to believe that they were even familiar with the story. The first text that bears witness to the story appears in the early 14th century, some 200 years after Rashi’s death, in Menorat HaMa’or of R. Isaac Abohav:

We have already found that the greatest of women who mocked the saying of the Sages that “women’s minds are easily swayed” (lit. lightweight), went astray in the matter, as is written in the first chapter of Avodah Zarah, that “R. [Meir] went and fled to Babylonia, some say because of the Episode of Bruriah”, and Rashi comments: “That once she mocked …”

Another reference to the Bruriah Episode appears several decades later in the responsa of Maharil:

For Bruriah, her end casts light on her beginnings: for some say she did not rely upon the Sages who said that women’s minds are easily swayed. And the greatest of all wise men, King Solomon, said: ‘I will take many [wives] and I will not be swayed and I will not founder etc.’ And here too, she relied upon her righteousness, that she would not founder, by means of [her] learning.

These two sources are the only references during the period of the Rishonim for the existence of the Bruriah Episode in Rashi, and both were written decades after the conclusion of the period of the Tosafists. What accounts for the silence of the Tosafists? Could this episode have passed silently through their study halls without stirring up a single question? Logic dictates that had the story been known to them, they would have commented on it.

Moreover, one of comments by the Tosafists on that very page addresses the issue of when a person is allowed to end his own life. And, lo and behold, this very question arises in the Bruriah story on the same page! The Tosafists should have clarified their position in light of Bruriah’s suicide, but instead, they bring a Talmudic source from another tractate, as if the Bruriah Episode simply did not exist.

We can safely conclude that this story was never seen by the Tosafists because, as we have suggested, Rashi never wrote it; it is, rather, the work of an anonymous student from a later generation. It stands to reason that the student found the story in a baseless source and chose to accept it for lack of any alternative explanation for the Bruriah Episode. The student even copied the story in the margin of Rashi’s commentary. Thereafter, the scribe who copied the manuscript mistakenly inserted the story into the body of Rashi’s words. From there, it spread to other versions of Rashi’s commentary until, by the time of the Maharil (and perhaps earlier), the story was assumed to have originated with Rashi himself.

At this stage, we wish to proffer a new chapter, a literary one, to the body of research about the Bruriah Episode. This is not the only personal story that the Talmud relates without detailing its content. The last chapter of Pesaḥim tells of the deathbed charge of R. Judah HaNasi concluding with the phrase, “Do not sit on the bed of an Aramean woman.” The Talmud offers several reasons for this statement and concludes, “Some interpret this to mean an actual Aramean woman, because of the Rav Papa Episode.”

What is the Rav Papa Episode? Here, too, as with the Bruriah Episode, the Talmud leaves out the details. However, in contrast with the Bruriah Episode about which we know nothing other than what is found in Rashi, the Ge’onim were privy to a tradition regarding the particulars of the Rav Papa Episode. In fact, there are many versions of the episode brought by the early Rishonim that seem to be based on an early common source.

As we have been dealing with Rashi, we will begin with his version of the Rav Papa Episode:

There was an Aramean woman who owed him [Rav Papa] money and he entered her home every day to collect [the debt]. One day, she strangled her son and left him on the bed. When Rav Papa entered, she said to him, ‘Sit here while I go bring your money.’ He did so. When she returned, she exclaimed, ‘You killed my son!’ and he fled the city.

A simple comparison between this story and the Bruriah Episode reveals that they bear a clear resemblance to one another. Both stories deal with an undisclosed incident in the Talmud, introduced by the phrase, “And some say it was because of the matter of …” Both stories begin with the tale of a woman. Both describe a regular series of encounters between a man and this woman, both feature death by strangulation, and both feature a similar outcome, namely, a flight to another land. In contrast with the Bruriah Episode, these words are certainly those of Rashi. Rashi’s grandson, Rashbam, also maintains Rashi’s version (in his commentary to Pesaḥim), and as we will see, Rashi refers to this story in Berakhot 8b as well. In general, the Rav Papa story is free of startling elements that contradict all that we know, unlike the Bruriah Episode.

The literary comparisons exist not only in motif, but also in structure:

1. “One time she [Bruriah] mocked,” in the Bruriah Episode parallels “There was one Aramean woman” in the Rav Papa Episode.

2. “He urged her day after day” parallels, “He entered her home every day.”

3. “And when she found out, she strangled herself” parallels “One day she strangled her son.”

4. “R. Meir escaped to Bavel” parallels “He fled the city.”

An examination of the alternate versions of the Rav Papa Episode sharpens the connection between Rashi’s version of it and the Bruriah Episode. Besides Rashi and Rashbam, who present the version of the Rav Papa Episode of the French scholars, there are four additional scholars of the same period who present an entirely different version of the story. R. Ḥananel and R. Nissim Gaon, who lived in North Africa in the generation prior to Rashi, bring a version that they received from their teachers. Thus writes R. Nissim Gaon:

It is related that Rav Papa lent money to a gentile man. When Rav Papa began to press him to repay the loan, the gentile decided to libel him, to avoid repayment. What did he do? He took a dead baby, placed it on his bed, and covered it with clothing so that nobody would detect it. Then he said to Rav Papa, ‘Come to my house with me and I will give you the money I owe you.’ Rav Papa went with him and entered the house. The gentile said, ‘Sit on the bed.’ Rav Papa took notice of the things on the bed before sitting down and discovered the dead baby hidden among the clothing. He realized that he was being set up for a false accusation.

And this episode was transmitted to me by my teacher, the holy sage, Rabbenu Ḥushiel, head of the rabbinical academy, of blessed memory. And I also found it in responsa of the Ge’onim.

According to R Nissim Gaon, Rav Papa’s debtor was a man who took the body of an anonymous child and attempted to frame Rav Papa with it, but R. Papa sensed the plot. The version of R. Ḥananel, the son of R. Ḥushiel, is similar to R. Nissim Gaon’s, but told tersely:

That an Aramean man owed him [Rav Papa] money, and he went to the man’s house to collect. This Aramean had a child who had died and was lying on the bed. When Rav Papa entered, the man instructed him, “Sit on the bed.” When Rav Papa sat down, the man shouted, “You killed my son!”

The prime difference between this version and that of R. Nissim Gaon are that this was not an anonymous child, but the child of the debtor (similar to Rashi’s version), and the debtor was able to successfully frame Rav Papa with the child’s death. This also appears in the version of Ra’avan (R. Eliezar bar Nathan), the preeminent rabbi of Ashkenaz at the end of Rashi’s generation. Similarly, R. Nathan bar Yeḥiel, author of the Arukh, who lived in Rome at the time of Rashi, cites a similar version which is distinguished by the fact that it is written in Aramaic, and also adds a twist: that the gentile brought witnesses against Rav Papa:

A certain Aramean owed [Rav Papa] money. He went to collect. When he reached the house, the man said, ‘Sit on the bed.’ There was a dead child there. The man brought witnesses and when they found Rav Papa sitting on the bed, he said to Rav Papa ‘You killed him!’

It is evident that these are four versions of the same core story that developed over the years from the original version. Rashi’s version, however, is an entirely different story, with four new elements that do not appear in any of the other versions:

1. The debtor was a woman, not a man.

2. Rav Papa visited her home to collect the debt on a regular basis.

3. Her son did not die naturally, but she strangled him.

4. As a result of the incident, Rav Papa was forced to flee to another land.

In other words, the four new elements in Rashi’s version of the Rav Papa Episode are identical to the common motifs shared by the Bruriah Episode!

In my opinion, the numerous parallels between the story elements cannot be coincidental. It is hard to know the definitive source of these parallels, but it is possible to offer the following explanation: The Talmud describes two incidents introduced by the phrase, “Some say”, which go on to describe personal stories whose details are unknown. With respect to the Rav Papa Episode, there is an ancient Ge’onic tradition. But with respect to the Bruriah Episode there is no information whatsoever. This lacuna triggered an attempt to fill in the gaps in the Bruriah story.

It is possible that over the course of time, this gave rise to the Bruriah narrative, as influenced by the details of the better-known Rav Papa Episode and its central themes. Alternatively, it is possible that the two episodes were written or constructed by the same author, which would account for the similarities between them. According to this hypothesis, it makes sense to speak of an early collection of stories from which Rashi chose to take his version of the ‘Rav Papa Episode;’ and then, over time, it made its way from there into his interpretation of the Bruriah Episode, which is far more dubious and without parallels in the works of the Ge’onim.

As many have already noted, it is almost certain that this version is not an original part of the Talmud, but was inserted during the period of the Rishonim. It does appear in some printings and manuscripts. However, as noted by R. Raphael Nathan Rabinowitz, author of Dikdukei Sofrim, in ms.Munich, the story is surrounded by parentheses and the margin contains the comment, “This is not from the language of the Talmud, and is a commentary.” Also, in ms.Paris, the story is entirely absent. There is also proof from R Nissim Gaon’s introduction to Sefer HaMafteaḥ, in which he shows that the Talmud sometimes records stories that “are not from our Talmud nor the Talmud of Eretz Yisrael.” The examples he cites include “that which is said in Berakhot and Pesaḥim regarding not to sit on the bed of an Aramean woman because of the Rav Papa Episode.” Here is clear-cut evidence that, during the transition period between the Ge’onim and the Rishonim, the Rav Papa Episode was not found in the Talmud. This is also evident from R. Nissim Gaon’s commentary on the Talmud itself, which concludes with the words, “And this incident is known through a tradition from my teacher, our master, the holy rabbi, R. Ḥushiel, head of the academy, of blessed memory. And I have also found it similarly in the responsa of the Ge’onim. ”To use the phrase of the redactor of the Sefer Ha’Arukh HaShalem, R. Ḥanoch Kohut, “Because of this, there is no doubt that the story of the Rav Papa incident is not brought in any fashion in either Berakhot or Pesaḥim.”

We are left with one question: What is, in fact, the Bruriah Episode? Thus far, we have related to the Bruriah Episode as yet another instance wherein the Talmud references a matter obliquely without detailing its content. We have also been working under the assumption that the only one of the Rishonim who addressed the Bruriah Episode was Rashi (and, in his wake, Menorat HaMa’or and Maharil). However, in fact, there is an additional reference to the Bruriah Episode among the Rishonim, albeit minimal in nature. Perhaps for this reason, the reference was overlooked by most of those who have addressed the Bruriah Episode. But I believe that buried within this reference is an important key to our issue.

R. Judah bar Kalonymos of Speyer, who was the teacher of the Rokeaḥ, R. Elazar of Worms, and lived in the generation after Rashi, authored a work entitled “Genealogy of the Tanna’im and Amora’im.” R. Judah’s book systematically presents the life and works of the Talmudic Sages. One of the entries is devoted to Bruriah, detailing her halakhic activities. At the end of the entry, R. Judah lists some acts of Bruriah mentioned the Talmud: “And the Bruriah Episode in Chapter 1 of Avoda Zara; and in Eruvin Chapter 5 where she expounded …”

A close reading of R. Judah of Speyer’s words reveals that in mentioning the Bruriah Episode, he sends the reader to the first chapter of Avodah Zarah. It goes without saying that nearly all Talmudic manuscripts of his time did not include Rashi’s commentary. In other words, in his opinion, the story of the Bruriah Episode is contained in the Talmud itself!

As we know, the Talmud ends the story with R. Meir’s flight to Bavel and with the phrase, “Some say it was because of this episode [hai ma’aseh], while others say it was due to the Bruriah Episode [ma’aseh d’Bruriah].” The common assumption has been that “hai ma’aseh” [”this episode”] refers to the entire sequence of events brought immediately prior, from beginning to end. However, based on the words of R. Judah of Speyer, we can read the Talmudic passage with a different assumption, dividing the long sequence into two separate episodes, as we shall presently see.

Where does the “Bruriah Episode” appear in the Talmud? The answer is simple: “Bruriah the wife of R. Meir, was the daughter of R. Ḥanina b. Tradyon. She said to him, ‘My sister’s captivity in a brothel is a shame upon me.’ R. Meir took a purse of coins and went …”—This is the Bruriah Episode!! Although most of the story deals with the actions of R. Meir, the Talmud does not open by saying, “R. Meir was the son-in-law of R. Ḥanina b. Tradyon, whose daughter was captive in a brothel.” Rather, it establishes Bruriah as the focus of events. Bruriah is the thread connecting the characters in the story: She is R. Meir’s wife, R. Ḥaninah b. Tradyon’s daughter, and she is the one with a sister who needs to be rescued. Bruriah is the protagonist who initiates the developments: She directs her husband to set out on the rescue mission in order to redeem the family’s honor—her family.

And what is “hai ma’aseh, this episode”? Apparently, “this episode” refers to the second half of the story, that takes place some time afterwards. This second narrative describes how the guard is interrogated and reveals R. Meir’s actions to the Romans. They search and eventually find him, but he eludes them via quick thinking and by miraculous intervention.

This reading of the Talmud not only makes sense of the Bruriah Episode but also stands on its own merits, for several reasons:

1. The conclusion, “he arose, fled, and went to Bavel.” The flight concludes the narrative, with the implication that it was precipitated by the events described. It stands to reason that the Bruriah Episode is part of this unhappy chain of events vis-à-vis the Romans, and not a completely separate episode (as in the commentary attributed to Rashi) with no connection to the preceding events.

2. Splitting the story into two episodes makes sense from a literary perspective. The first half opens with Bruriah, deals with her efforts to rescue her sister, and ends happily—the captive sister is returned. At this point, the chronology of the story jumps ahead, Bruriah’s sister exits the story, and the Bruriah Episode ends. The second half of the story, “this episode,” continues from a later point in time, no longer revolving around the rescue of Bruriah’s sister, but rather around the rescue of R. Meir himself. Although the incident underlying “this episode”—namely, R. Meir’s rescue of Bruriah’s sister—does not itself appear in the second story but rather in the Bruriah Episode which precedes it, so too the incident underlying the Bruriah Episode—namely that her sister was held captive in a brothel—does not appear in the Bruriah narrative, but rather in the story which precedes it in the Talmud, which deals with the execution of Bruriah’s parents, R. Ḥanina b. Tradyon and his wife, and the placing of their captive daughter in a brothel.

3. The notion that the Talmud places before us two separate episodes is also hinted at in the Talmud itself, in the words of the guard to the investigators, “such-and-such was the episode”—in other words, the prior episode, the Bruriah Episode.

What is the difference between R. Meir fleeing due to “this episode” and him fleeing due to the “Bruriah Episode?” The Bruriah Episode presents the family’s entanglement with the Roman authorities, who were after Bruriah’s family, and R. Meir as well due to his marriage into the family,as well as his efforts to rescue his sister-in-law from their clutches. To escape their net, he was forced to flee to another land, not under Roman rule. By contrast, a different element is at the core of the second episode, that of shame. To escape the Romans pursuing him, R. Meir was forced to simulate eating non-kosher food or embracing a prostitute, and likewise he was seen publicly entering a brothel. Although his behavior was justifiable and not forbidden, and although he did not actually engage in forbidden acts but merely appeared to do so, it would have been difficult to explain this to the public, and could have caused a desecration of God’s name [ḥilul HaShem]. To prevent this, R. Meir was forced to flee far away to Babylonia where people would not have heard the story, and R. Meir would not be associated with these acts.

Even if we ourselves would not have read the Talmud thus of our own accord, R. Judah of Speyer paved the way for us. According to his position, the Bruriah Episode was right in front of the reader’s eyes the entire time. This reading fits well with the version of R. Nissim Gaon that we cited earlier, in which R. Meir fled to Babylonia with his wife. Whether the escape was due to Roman pursuit of R. Meir, Bruriah and her family, or whether it was to prevent embarrassment and desecration of God’s name, either way it would have been natural for R. Meir to flee together with Bruriah and not alone.

Let us now return to where we started, to the hashkafic questions that the Bruriah Episode raises in our generation in both the Torah world and the religious-feminist world. Practically speaking, we are no longer forced to accept the story in Rashi as part of Bruriah’s life history, and those who wish to delve into her background now have a concrete basis for ignoring this story. For educators who reach this passage in the Talmud and are deliberating how to teach it, we now have the version of R. Judah of Speyer, which allows us to locate the Bruriah Episode in the Talmud itself.

Reprinted from Eitam Henkin, “Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History,” eds. Chana Henkin and Eliezer Brodt (Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2022), with permission of the Henkin family.

By the time of his death at age 31, Rabbi Eitam Henkin had authored over 50 articles and three books. A graduate student at Tel Aviv University, he was renowned both for his halachic writings and for his mastery of the byways of the rabbinic world of the 19th and 20th centuries. He was murdered by a Hamas terrorist cell together with his wife, Na’ama, a graphic designer, in front of their four young children on Ḥol Ha-Moed Sukkot, 2015. Their deaths were a great loss to both the Torah and academic communities.