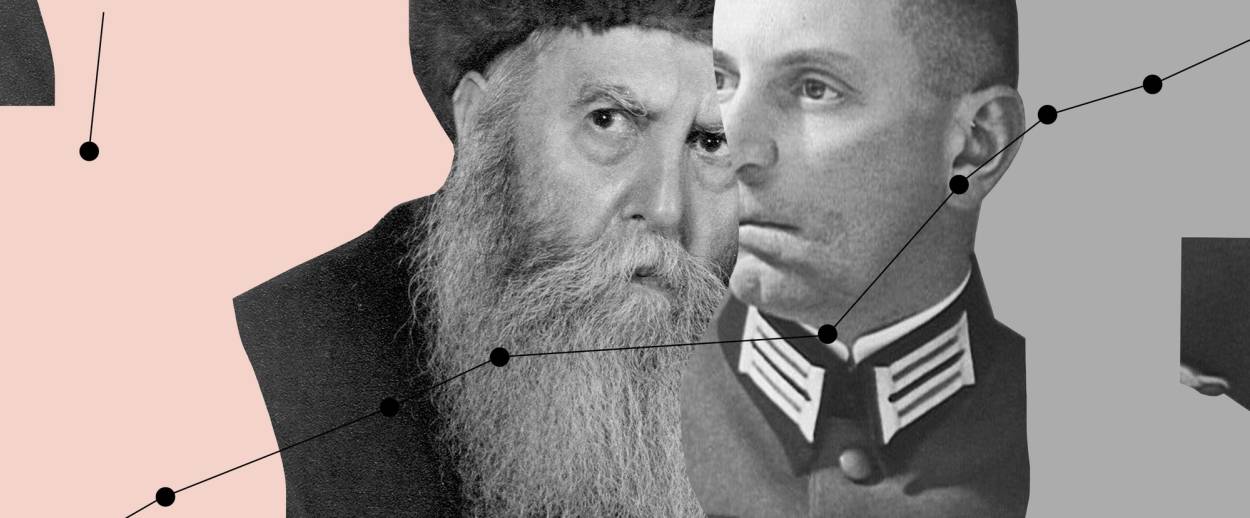

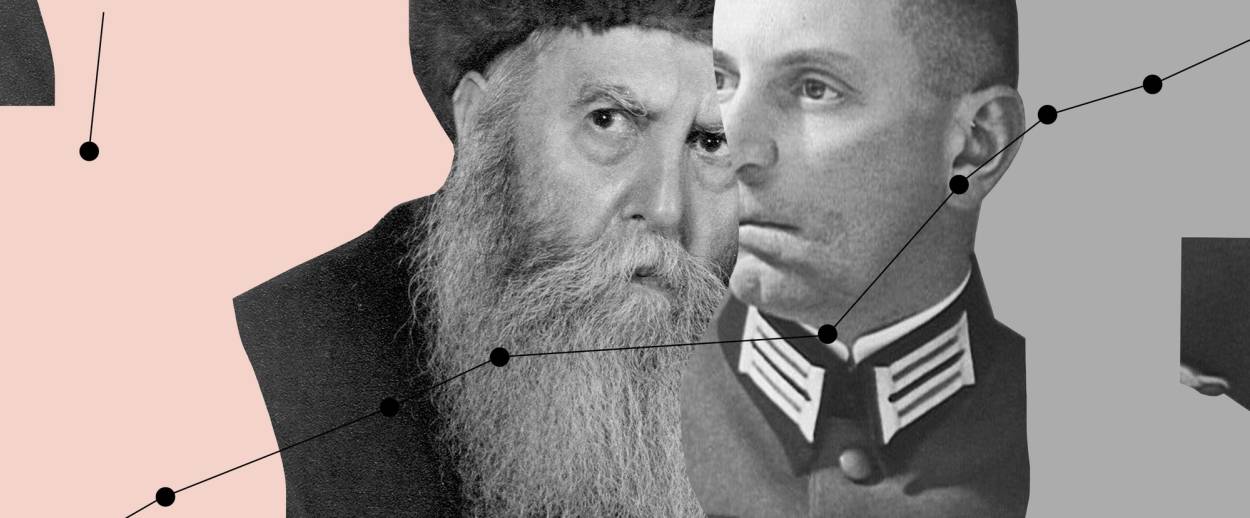

The Nazi Who Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe

The surprising story of how the sixth Chabad rabbi made it out of Warsaw

When war broke out on Sept. 1, 1939, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, was staying in Otwock, a resort town outside of Warsaw where he’d established a Chabad yeshiva. The Rebbe was suffering from multiple sclerosis, he was overweight and a heavy smoker. He walked with difficulty.

The journey from Otwock to Warsaw was only 60 kilometers, but perilous. The Luftwaffe’s Stutka war planes bombed and strafed traffic and destroyed rail lines, leaving mutilated bodies and dead horses littering the road. Roadside ditches were filled with Poles hiding from the planes, which they called “death on wings.”

The Rebbe arrived in Warsaw with his family and a group of students, hoping to catch a train to Riga, Latvia, where Mordecai Dubin, a Chabad follower and member of the Latvian parliament, had arranged Latvian citizenship for the rabbi and his family. But Rabbi Schneersohn found the Warsaw train station destroyed and was forced to seek shelter among Chabad followers in the city.

“They bombed all the Jewish neighborhoods, flattened them,” said Rabbi Joseph Weinberg, then a yeshiva student in Otwock who had followed the Rebbe to Warsaw. Rabbi Schneersohn went into hiding. “He would sit in the room writing memorim (articles) and his hand would shake from the bombing.” The Rebbe was taken from apartment to apartment in the beleaguered ghetto to avoid detection by the Nazis.

***

In America, Chabad was a relatively insignificant Hasidic movement with a small following. But one of its followers, Rabbi Israel Jacobson, who was in charge of a small Chabad synagogue in Brooklyn, contacted a few others in his congregation. Mounting a campaign to save the Rebbe, they hired a young Washington lobbyist named Max Rhoade to advocate their cause, billing Rabbi Schneersohn as the world’s leading Torah scholar with a huge following.

Rhoade contacted congressmen, senators, government officials, presidential advisers, and even involved Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis in the hope of finding a way to save the Rebbe. His campaign soon gathered momentum.

Cables began to fly back and forth among Riga and the United States, Poland, and Germany, while in Warsaw bombs fell and the Nazis hunted for Jewish leaders.

On Sept. 22, U.S. Sen. Robert Wagner sent a telegram to U. S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull: “Prominent New York citizens concerned about whereabouts of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, … present location unknown.”

On Sept. 26, Mordecai Dubin wrote to Rabbi Jacobson in Brooklyn: “Save lives. Rabbi and family. Try every way. Every hour more dangerous. Answer daily what accomplished.”

On the same day, Phillip Rosen, head of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s office in Europe, wrote to the U.S. representative in Riga: “Greatly interested world famous rabbi Schneersohn … now Muranowska 32 Warsaw. Urge your doing utmost to effect his protection and removal to Riga …”

On Sept. 29, a Chabad supporter, attorney Arthur Rabinovitz, wrote to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis: “… am turning to you for any aid you can render possibly through Ben Cohen … feel justified in troubling you by extreme danger to Schneersohn’s life and his great moral worth to world Jewry.”

At the time, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, running for his third term, was reluctant to do anything overt to help alleviate the plight of Europe’s Jews. Isolationism was in full bloom as was a powerful pro-Nazi movement in the U.S. led by Father Charles Coughlin. Coughlin, a Canadian-born Catholic priest, rabid anti-Semite and admirer of Adolf Hitler, had a weekly radio program that at its height reached an audience estimated at tens of million of listeners. Roosevelt had his own doubts about the wisdom of relocating Jews to America.

However, Rhoade would not be deterred. He badgered Justice Brandeis and Roosevelt’s adviser Ben Cohen, who in turn put pressure on men like Henry Morgenthau, then economic adviser to Roosevelt. Saving the Rebbe became a major Jewish struggle, at least on the upper rungs of the communal ladder.

Cohen recalled that U.S. diplomat Robert Pell had attended the Evian conference on refugees in France in 1938 and had made friends with the German diplomat Helmut Wohlthat. On Oct. 2, Cohen wrote to Pell, then attached to the State Department’s European Affairs division: “I am turning to you for advice. I would appreciate any assistance you might be able to render.”

Pell then contacted U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull: “(Mr. Cohen) … appealed to me because of the arrangement which I had with Wohlthat last winter. … Wohlthat had assured me that if there was any specific case in which American Jewry was particularly interested, he would do what he could to facilitate a solution.”

According to Menachem Friedman of Bar Ilan University, “His (Wohlthat’s) interest was to maintain good relations with the Americans. And the price that had to be paid for these good relations was this Rabbi from Poland. And that wasn’t a high price.”

On Oct. 3, Hull sent a telegram to the U.S. consul in Berlin:“Wohlthat … might wish to intervene with the military authorities.”

The Roosevelt administration had decided to toss the Jewish community a bone to keep them quiet, and the bone was Rabbi Schneersohn.

According to Winfried Meyer of the Berlin Technical University, and an expert on the German military, “The only force who would be able to do anything was military intelligence since Warsaw was occupied by the German military and not by a civil administration, so Wohlthat contacted Admiral Wilhelm Canaris,” head of the Abwehr, German military intelligence.

Canaris called one of his officers, Major Ernst Bloch, a highly decorated soldier, into a meeting. According to Bryan Mark Rigg, author of Rescued From the Reich, Canaris told Bloch that he had been approached by the U.S. government to locate and rescue the head of Lubavitch, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. “You’re going to go up to Warsaw and you’re going to find the most ultra-Jewish Rabbi in the world, Rabbi Yoseph Yitzchak Schneersohn, and you’re going to rescue him. You can’t miss him, he looks just like Moses.”

The Roosevelt administration had decided to toss the Jewish community a bone to keep them quiet, and the bone was Rabbi Schneersohn.

Major Ernst Bloch was a career spy. He’d joined the German army at 16, been severely wounded in WWI, and stayed in the army after the war. He’d been assigned to the commercial division that spied on visiting businessmen. Bloch was also half-Jewish. His father was a Jewish physician from Berlin who, like many other German Jews in that period, had converted to Christianity. Bloch’s mother was Aryan. “It was only by chance that he was half-Jewish,” said Meyer.

“He was what they call an assimilated half-Jew,” said Bloch’s daughter, Cornelia Schockweiler, a practicing Buddhist living in Mountain View, California. “He was not religious. He did not impart any religious feeling in me at all. He was a professional soldier who spent most of his life in the military. If Canaris told him to do something he would do it, no questions asked.”

Bloch was called a michlinge by the Germans. “The term michlinge was used for mutts, dogs, crossbreeds, a horrible term,” explained Bryan Rigg. Rigg estimates that 60,000 half-Jews and 90,000 quarter-Jews served in the German armed forces during WWII.

Winfried Meyer contends that Field Marshal Hermann Goering also knew about the rescue operation of the Rebbe since Wohlthat was one of Goering‘s closest associates. “Goering’s and Canaris’ common interest was to prevent the war in Poland from escalating into a world war, hoping that Roosevelt would arrange talks between Germany and Britain in order to save peace. They were glad to do the American government a favor by rescuing Rabbi Schneersohn.”

Bloch enlisted two other soldiers from the Abwehr and traveled to German-occupied Warsaw. According to Rigg, “He would go up to ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Jews, wearing a Nazi uniform with swastikas, and say, ‘I’m looking for the Rebbe.’ And they’d say to him, ‘Yeah, and we want to shave off our beards and join the German army.’ Then they would walk away.”

On Oct. 24, attorney Arthur Rabinovitz again appealed to Justice Louis Brandeis: “Received cable from Latvia … Rabbi Schneersohn at … Bonifraterska 29, Warsaw.” That address was passed on to Bloch.

***

November was a cruel month in the Warsaw Ghetto. Jews were ordered to wear the yellow Star of David on their clothing. There was little to eat. The Rebbe and his followers were hiding out from the Nazis.

Meanwhile, Ernst Bloch was scouring Warsaw for Rabbi Schneersohn. But when Bloch and his men arrived at Bonifraterska 29 they found the building had been destroyed.

On Nov. 13, Pell communicated information from Wolhthat’s assistant to Chabad lobbyist Max Rhoade: “Building at address given was completely destroyed. Impossible to ascertain whether Rabbi Schneersohn was in the building.”

The rabbi was losing weight and his health was fading. On Nov. 14, Rhoade sent a telegram to the Red Cross in Switzerland: “German military officer detailed to locate Rabbi Joseph Issac Schneersohn … Schneersohn not apprised officer’s mission. Hope you can devise method of communicating information to Schneerson … detailing of German officer done at request of Schneersohn’s friends … urgent … take advantage opportunity.”

“A telegram arrived that the Rebbe should turn himself over to the Gestapo,” said Rabbi Weinberg. The “Gestapo” was Major Ernst Bloch.

Another telegram was sent to Poland, hoping it would reach Rabbi Schneersohn. “German Military officer detailed to locate Joseph Issac Schneersohn Bonifraterska 29, old address Muranowsa 21, and also provide him safe egress from Poland to Riga.”

With great trepidation, the Rebbe told a messenger to contact Bloch.

Rabbi Schneersohn’s grandson, the late Barry Gurary, then a teenager, was in the room when Bloch’s men arrived. “It was so overwhelming. As soon as we got to the door they rushed right in,” remembered Gurary, a retired physicist, sitting in an easy chair in his New York apartment. “There was primarily one guy, and he used every dialect of German that you could think of. During the time the soldiers were there my grandfather was calm and composed on the outside. He was a sick man and it got to him after a while. He was a very strong personality, but not very strong physically. He was exhausted.”

Barking orders, Major Bloch commandeered a truck and loaded the Rebbe and his family aboard. “Bloch had to get the Rebbe out of Warsaw. He decided the best way to do this was to take him to Berlin, to throw the SS off the track,” said Bryan Rigg. Bloch put the Rebbe and his family on a train to Berlin.

The SS, run by Reinhard Heydrich, was highly suspicious of Canaris. Heydrich wanted to absorb the Abwehr into the SS. Should Heydrich’s SS get their hands on the Rebbe before the Abwehr, arrest and death were certain.

Gurary described the harrowing escape. “We had to go through various military checkpoints. with one person who was our escort. We marveled at his way of handling things.” The Rebbe and the other 18 in his entourage were dressed as Hasidic Jews, beards, sidelocks, women in wigs and covered hair. No disguise was possible. Bloch claimed they were prisoners. And he was on a top-secret mission.

“On the train … if a conductor came over, he (Bloch) would handle the conversation. The difficulty was making sure nobody kicked us out of the compartment we were in. I remember one episode when an angry German officer came up to us and said, ‘Why are these Jews sitting in the compartment when the officers are in the corridor?’ Bloch had to do quite a bit of explaining, and he did.”

“Once in Berlin,” said Rigg, “the Rebbe and his family were taken to the Jüdische Gemeinde, the Jewish community center in the Jewish quarter. There he met the Lithuanian ambassador to Germany who provided the Rebbe and his group with Lithuanian visas. The next day Bloch escorted them to the Latvian border and bid them farewell. The group continued to Riga and waited there for visas to the United States.”

“Crossing the Latvian border sure felt good,” said Barry Gurary. “We didn’t say a word. We were very quiet.” Only after they crossed, said Gurary, did they celebrate.

***

On Dec. 17, just over three months after the war began, Mordecai Dubin wrote to Rabbi Jacobson in Brooklyn, “Rabbi and family arrived well Riga.”

Next came the struggle to get the Rebbe into the United States.

Again, pressure was put on the Roosevelt administration by Justice Brandeis, Ben Cohen, and others. This was opposed by Breckenridge Long, then head of the Visa Section of the State Department. Long, an anti-Semite, suspected that any immigrant from Europe was a spy.

However, political pressure prevailed. A 1921 exemption to the visa quota of immigrants from Europe was invoked by the Rebbe’s advocates to allow him into the United States. The Rebbe was granted a visa as a religious “minister” with an active congregation awaiting him in Brooklyn and a bank account with $5,000 in it. Long reluctantly granted the visa.

The Rebbe arrived in the United States by ship in 1940 to great fanfare. A similar exemption was later applied to his son-in-law, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who arrived with his wife from Marseilles in 1941.

In 2010, two Israelis applied to Yad Vashem to recognize Wilhelm Canaris as a Righteous Among the Nations for saving Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. One was Rabbi Baruch Kaminsky from Kfar Chabad, and the other was Dan Orbach, then a young scholar at Harvard.

According to Orbach, “The Abwehr, German military intelligence, was the center of anti-Nazi activity and the majority of the espionage unit, especially the head of the unit, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris and his assistant Hans Oster, were members of the underground.” One of the Abwehr men, Hans Von Dohnanyi, was recognized as a righteous gentile by Yad Vashem, but not Canaris. Von Dohnanyi, Oster and Canaris were all executed by the Nazi regime before the end of the war.

Major Ernst Bloch was ousted from the Abwehr after a failed attempt on Hitler’s life that Bloch had no part in. He joined the civil guard defending Berlin against the Allies. He was killed during the fighting. When asked if she thought her father should be honored for his role in saving the Rebbe, Bloch’s daughter, who remembers being bounced on Wilhelm Canaris’ knee, said, “Should people like my father and Canaris who served in the army under Hitler, and maybe, on the side, tried to do something good, should they be recognized? I don’t know. Maybe not?”

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson went on to become the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, one of the most influential figures in the history of postwar American Judaism. As professor Menachem Friedman said, “After the war the western world was a different place. And in this world Lubavitch found a very central and important niche, so much so that if Chabad didn’t exist, someone would have had to create it.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Larry S. Price is an American-born Israeli filmmaker. This article was based on his documentary film, co-produced with Israel TV,The Rabbi and the German Officer.