Machines of War

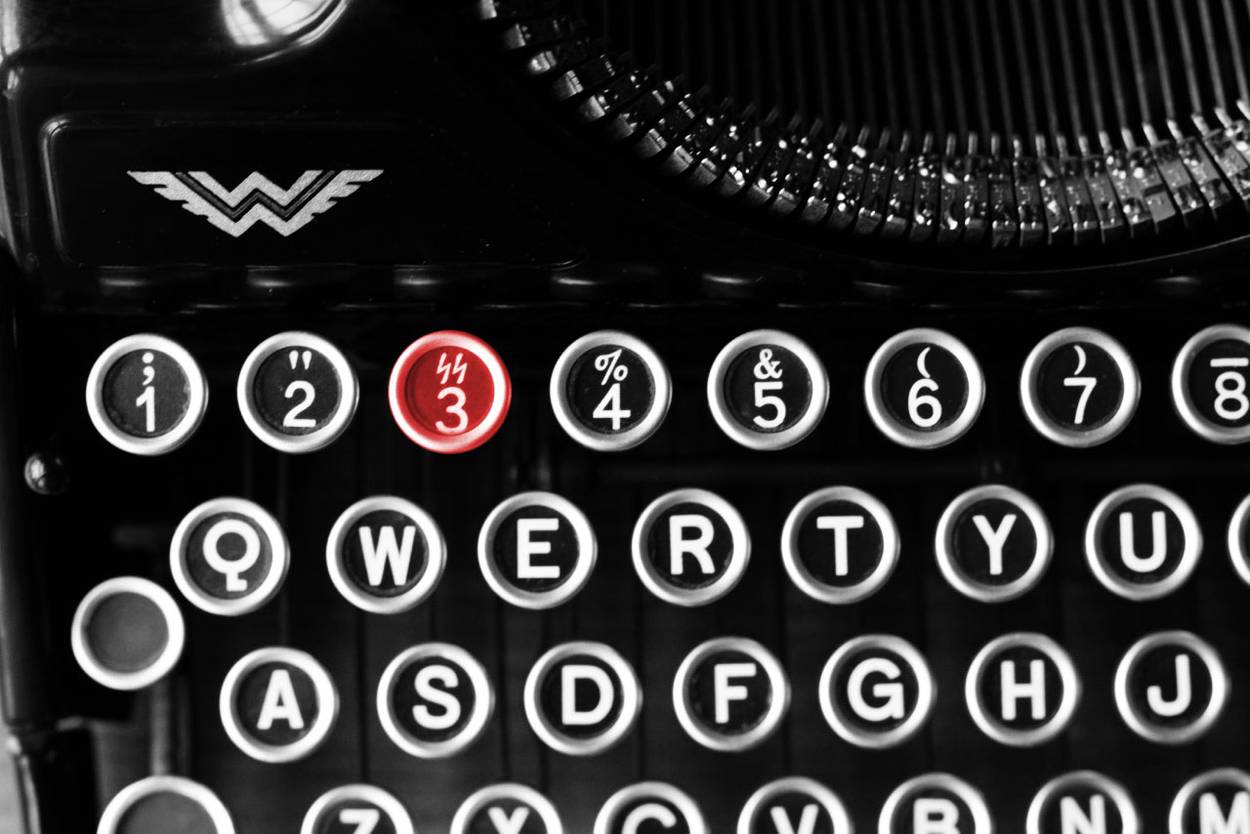

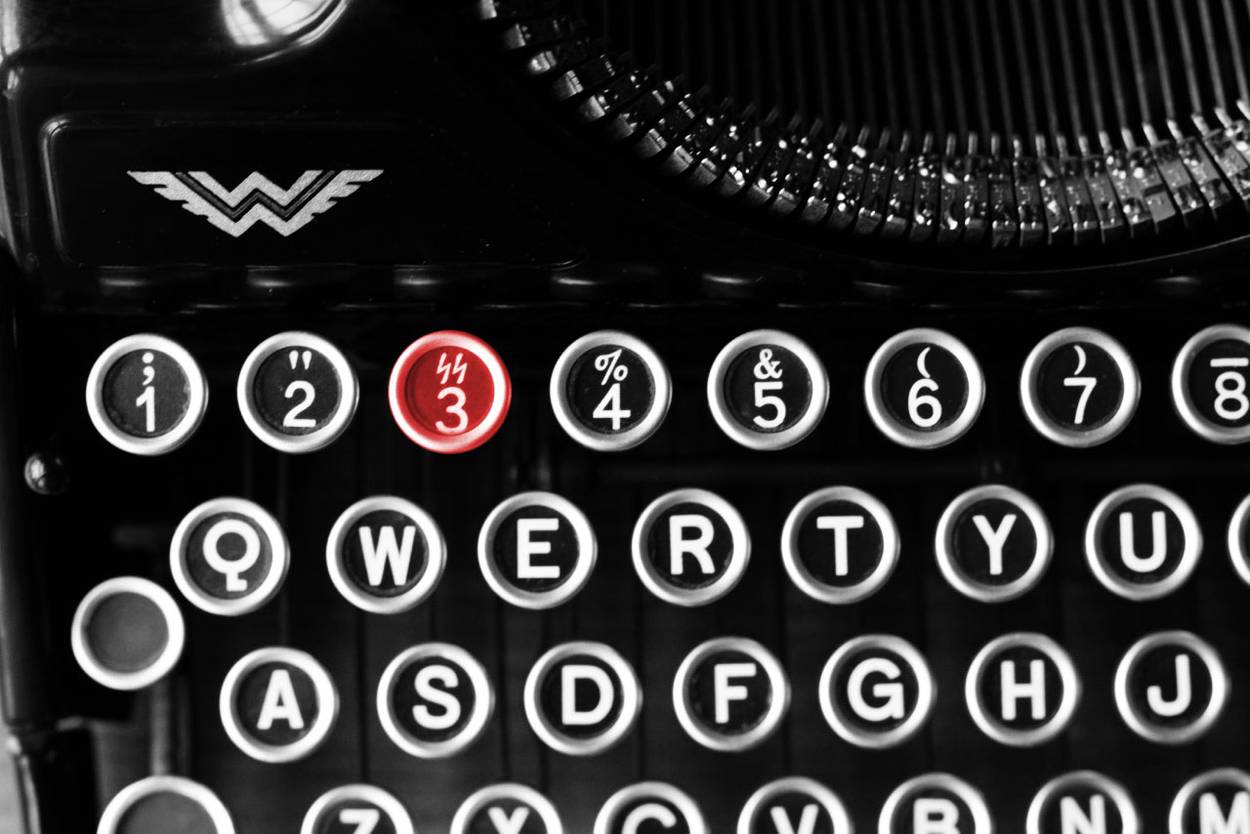

Some collectors have spent years on a quest for a rare relic—a Nazi-era typewriter with a key for the ᛋ ᛋ symbol

I recently asked the 5,000 members of the Facebook group Antique Typewriter Collectors why they wanted to own typewriters with a certain key. Specifically, a key with twin runic letters like lightning bolts: ᛋ ᛋ. The symbol stands for Schutzstaffel—the “SS”—the branch of the Nazi party tasked with organizing and carrying out the annihilation of European Jewry. It turned out I was reopening an old wound.

I joined the group on Facebook three years ago, shortly before traveling to a house in the hills outside Morgantown, West Virginia, to attend an annual gathering of typewriter enthusiasts. A hundred of us wedged our vehicles into the front yard and along a gravel road. Most people were far younger than the typewriters they’d brought along; the average human age was in the mid-forties. Men outnumbered women four to one. Two people in attendance had traveled all the way from Germany. I was struck by how familiar the group seemed. Inside jokes abounded. A kind of social hierarchy was just discernible. I often found myself sitting with the other first-timers, a little intimidated.

Some collectors attend the gathering hoping to find what’s known in the community as a “grail typewriter,” a reference to the Holy Grail. In early Arthurian legend, there’s only one Grail, and one knight worthy enough for it. Nowadays every collector has their own personal grail to search for. At the time, my own grail was a typewriter with a san serif typeface designed in the 1920s called Vogue. The defining feature of Vogue is a lowercase e with a sharply angled crossbar (think: ø). I’d been literally dreaming of that e. (The capital G is also elegant. How good my name would look in Vogue!) In planning my trip to the gathering, I’d contacted Mark, one of 10 group administrators, who offered to sell me his 1947 Royal Arrow with Vogue for $500. We met up, but I ended up passing on the sale. The road trip from Michigan had already been expensive, and anyway, I really wanted a Model P with Vogue, not an Arrow.

Mark owns about 200 typewriters. His local PBS station has interviewed him about his collection. He’s one of the most active members on the group page, and his posts have a knowledgeable, no-nonsense vibe. In his profile picture, he’s sitting with a typewriter in a folding chair in the sand. He’s wearing flip-flops, a camouflage hat, and a T-shirt with the logo “Appalachia ASP at Virginia Tech,” a Christian volunteer organization that repairs houses to make them safer from the elements.

One of Mark’s grail machines is his 1942 Royal Arrow with “U.S. Navy” stamped on the paper tray (his father was in the U.S. Navy). Another is his 1943 Olympia Robust “with the runes”—the ᛋ ᛋ key. The Robust was designed for “field use” and has a ribbon cover built to deflect shrapnel. In one post, he puts his grails together in a picture: “Both sides of the war: check!”

A typewriter with an intact ᛋ ᛋ key can sell for over $1,000; after the war, these keys were sometimes filed off. eBay policy prohibits selling them, but they’re often bought before they’re flagged. At least 20 members of the typewriter group own such a machine, and while there are detractors in the community, such ownership is generally celebrated. I don’t think these people are neo-Nazis; I think they mean well. That’s why this phenomenon troubles me.

It seems like magic that typewriters still work. Walter Benjamin, who died in 1940 fleeing the Nazis, described the “aura” of an original work of art, what’s missing from any reproduction, as “its unique existence at the place where it happens to be … the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning … its testimony to the history which it has experienced.” That explanation also captures one of the joys of owning a typewriter. Although they began on the assembly line as “reproductions,” over time, each one gains a kind of aura—it becomes singular, original.

Some typewriters arrive with troves of history. Almost always, there is hair from the previous owner(s) stuck inside them—at the very least. Once, I bought a 1956 Princess 100 on Craigslist from a woman in Ohio. Inside its case was a sheath of papers. There was a letter dated 12 October 1960 from Nürnberg to Toledo, which simply read “Meine leibe Ester und Karl …” with what might be the intended reply—all it says is “Leibe Tante uAlle”—on airmail paper bearing the letterhead of TS Hanseatic, a German cruise liner that caught fire in 1966 and was scrapped. There was the St. Mark’s Lutheran Church bulletin for “Girl Scout Sunday” 1961. There were notes on France (“the only country that spreads over more of Europe is the huge Soviet Union”) and architects (“Although there are some outstanding women architects, only about 1 percent of registered architects are women … I wanted to be an architect all my life, and I still do.”)

“Was this yours?” I asked the woman, looking over the papers. It wasn’t. Her daughter’s ex-boyfriend gave it to her daughter—he’d also bought it on Craigslist.

So when Mark said that a small disappointment of his SS typewriter is that he was unable to trace its specific history, I can almost relate. I love having this connection to a person I’ve never met and never will meet, because she grew up: a Girl Scout named Ester from Toledo, from 1961, who wants to become an architect. What I can’t understand is why someone would want that kind of connection with an SS officer.

Nobody in the group will dispute that, like trains, typewriters were essential to the scale of the Nazi genocide. Typewriters were the engines of communication within the massive network that orchestrated the Holocaust. Transports lists, call-up notices, orders of the pellets that made the gas, Zyklon B, were written on typewriters. Typewriters ensured accuracy and speed, and it took accuracy and speed to round up and kill two-thirds of the European Jews in a matter of six years.

A defensive refrain of those who own SS typewriters is that it is often impossible to know who used the typewriter and whether it was used at a concentration camp or elsewhere, in a field office, in a Berlin apartment. They claim that any German typewriter of the era could have been used by a member of the SS or by a member of the Resistance. Another collector put it this way: You don’t avoid walking under the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin just because Nazis once walked under it.

But that would only make sense outside the collector context, someone using a typewriter in spite of its ᛋ ᛋ key. Mark and others want them because they have an ᛋ ᛋ key. These typewriters are their grails, not the family glassware they inherited. It’s like flying to Berlin in order to walk under the Brandenburg Gate, but it’s more than that, because you can’t take a Brandenburg Gate home with you.

In his PBS interview, Mark says, “Particularly the Nazi machine is fun to use because that’s one that has a lot of negative stigma … But I see it as an inanimate object …There’s nothing negative about it to me. It’s a tool that can be used by anybody that was used by people who were,” he pauses, “bad.” That doesn’t make sense either. If the typewriter is fun for him to use because of its stigma—its history, its aura—then the typewriter is no longer an “inanimate object” to him. The stigma is animating it; he simply doesn’t find that stigma “negative.” Moreover, it’s not the stigma of Nazi symbols in general that gives Mark’s typewriter its power, it’s the possibility that his particular machine was in some way involved in what happened. Mark has warned that you have to be careful when buying an SS typewriter because there are a certain number of counterfeits out there: newer ᛋ ᛋ type slugs fitted onto older bodies. Counterfeits do not have the claim on the Holocaust that real SS typewriters do.

According to Mark and others, to destroy these typewriters instead of collecting them—“going all Kristallnacht on them,” as Mark called it—is to do what the Nazis did in burning books. One moderator wrote, “If we erase the SS keys and such things, we effectively allow people to deny the existence of what has happened … In some ways, owning one of these machines is a great responsibility.”

Personally, I don’t believe that the members of the group are actually under the illusion that failing to preserve the hundred or so SS typewriters in private collections, as functional machines, will begin a process in which the Holocaust is forgotten. These collectors are not worried about the Holocaust. They’re worried about the typewriters. That’s why Mark believes that “there can hardly be a worse fate” for SS typewriters than going to museums. In one post, he wrote, “Sometimes they disappear into storage; often they are not labeled great or just used as background props.” In another: “One of the typospherians donated a Robust to a Holocaust Museum, and I was in town and went to see it, and the label just said ‘German Olympia Typewriter,’ and it was off in a corner. They didn’t even bother to point out the runes.” In other words, he believes that museums, though they honor the memory of the people who died in the Holocaust, tend not to sufficiently honor these typewriters for what they are. He went to see the typewriter.

It’s telling that one collector described SS typewriters as “relics.” In Wagner’s “Parsifal,” keeping the Grail and other relics safe was the holy task left to King Amfortas and his monastic knights. Not because the life of Jesus might be forgotten without it (the Bible wasn’t going anywhere)—but because the Grail had mystical power in itself. Relics have a power all their own.

“I can’t even adequately put into words why I wanted one,” one member wrote. “It is an exercise in contradictions and duality that I lack the faculties to describe.” Mark has said that he is half-Polish and had relatives die in World War II. In fact, when a woman claimed to have friends whose relatives died in Auschwitz and expressed “distaste” for Nazi symbols, he responded that he too had “family that suffered at Auschwitz.” And his point, he said, was “simply” that he would like an SS typewriter.

Maybe it’s a fool’s errand to try to uncover why certain people are fascinated with certain things. A collector who volunteers each year on an island, helping tag at-risk migratory birds, wrote, “I am fascinated by Soviet typewriters, but that doesn’t make me a communist. I think [an SS typewriter] is cool.” When asked why he would want one, he wrote, “Doesn’t matter.” I replied, “I guess I wish it would matter to people.” He responded, “This isn’t a political place. It’s a safe space for all typewriters, one last realm of magic.” Soon afterward, he posted in support of “Typewriter Neutrality,” encouraging members to “keep scrolling or choose not to see” posts that might upset them. “If something is not at all typewriter-related, our moderators will squash it,” he wrote.

There was a reason why ᛋ ᛋ was written in ancient runic characters and why the SS considered itself a group of Teutonic knights and housed its “school” in a castle. Runes means “a symbol with mysterious or magic significance … an incantation.” Reich means “realm.” Himmler was calling something up. The symbol ᛋ ᛋ was meant for you to think it was cool. It was meant—if you felt like an outsider in your own country, in your own time—to offer something cool, something powerful, maybe even magical, with which to associate yourself. A relic of sorts to guard and defend.

Apparently, the symbol is still effective.

Graham Cotten recently finished a fellowship in fiction at the University of Michigan’s MFA program. He is at work on his first novel. Find him on Instagram @TheTypewriterForest.