The Journalist Who Fell Asleep on Prince

A new memoir from Neal Karlen, the writer formerly known as Prince’s favorite reporter

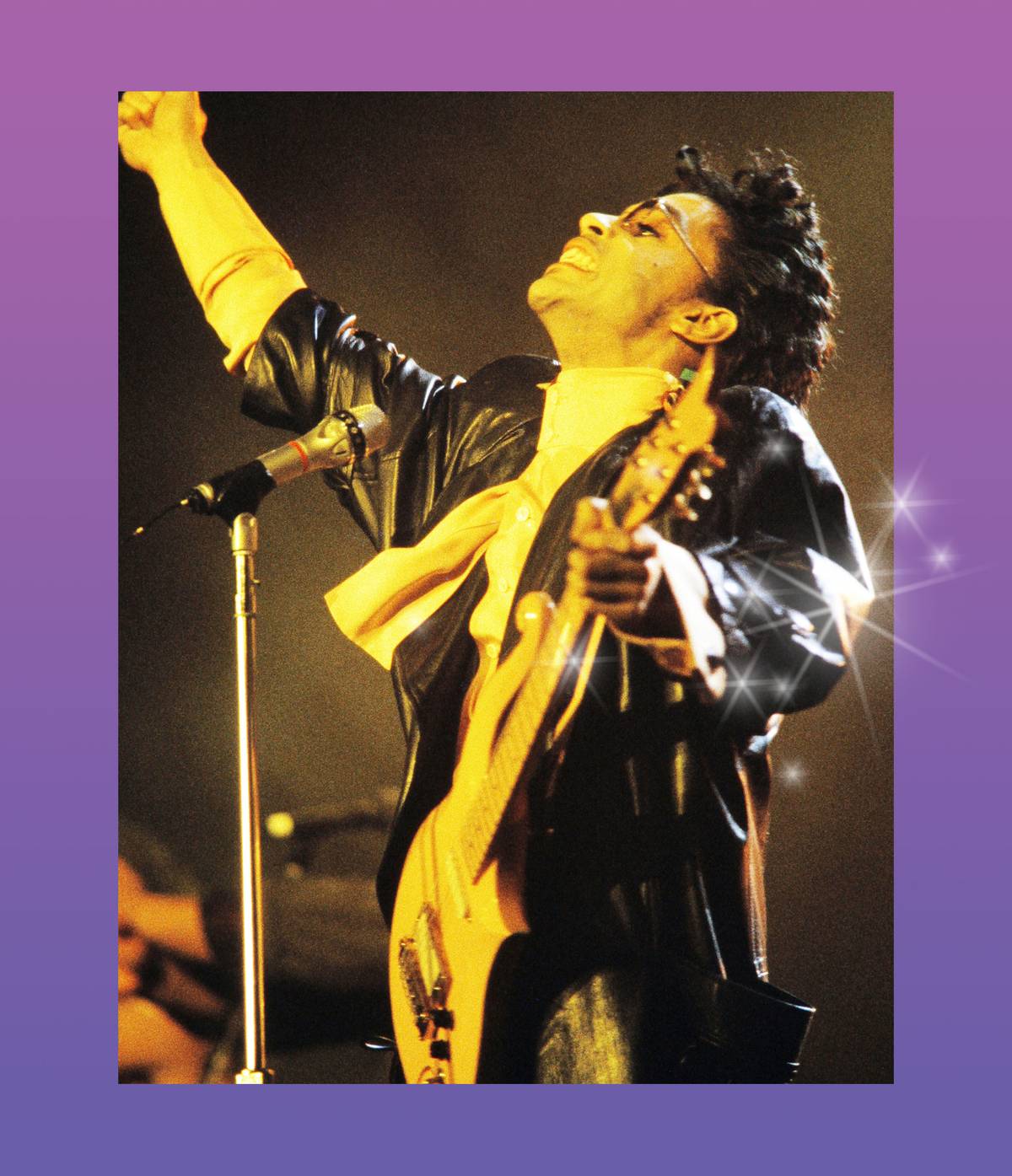

I remember when Neal Karlen was invited to interview Prince, the most famous rock star on the planet, for a Rolling Stone cover story in 1985. Neal had been invited by Prince himself, who at that point had maintained a three-year media silence, a veritable epoch in rock ’n’ roll time. The era began with the release of Prince’s first top 10 hit, “Little Red Corvette,” followed by “When Doves Cry,” the first No. 1 single from the movie Purple Rain, then the release of the movie itself, whose soundtrack took only eight days to reach No. 1, where it stayed for an astonishing 24 weeks. It continued with another No. 1 hit from the movie, “Let’s Go Crazy,” by Prince and The Revolution, and if that weren’t enough, shortly after Prince picked up his Oscar for best original soundtrack for Purple Rain, his seventh album, Around the World in a Day, featuring “Raspberry Beret” and “Pop Life,” also went to No. 1 in the United States.

By then, press was possibly beside the point. After all, in 1980, Robert Christgau, in his review of Prince’s Dirty Mind for the Village Voice, declared: “Mick Jagger should fold up his penis and go home.”

In any event, the reason I knew about Neal’s summoning by “the dynamic funk enigma that is Prince” is that we were both then toiling at Newsweek, cub reporters who had tumbled out of our respective college dorm rooms and into the skyscraper offices at 444 Madison Ave., where we were variously biding our time over savagely tedious tasks and battling the fires of Friday-night closings. Moreover, we had formed an exclusive club of two as the only Newsweekers who had just written cover stories for the far groovier Rolling Stone, eight blocks north on Fifth Avenue but 100 million cosmic miles away. Mine had been a story on the genre-busting TV show Miami Vice. And Neal had written about Jamie Lee Curtis, then starring alongside John Travolta in Perfect, the ‘80s self-referential paean to Rolling Stone, love, and gym life.

But, this. This was big, even for the glitzoid, over-the-top ’80s. The story that would emerge, “Prince Talks: The Silence is Broken,” would be Neal’s first of three cover stories for Rolling Stone about Prince. And it would mark the beginning of a friendship that would last 31 years until Prince’s death alone in an elevator in Paisley Park, his compound in Chanhassen, Minnesota, in a manner that Prince had predicted in that very first interview, while speaking about the tunes and tones in his head that caused him to make music all night, sometimes for 20 hours straight, with the help of studio engineers who worked in shifts. “‘One of my friends worries that I’ll short-circuit. We always say I’ll make the final fade on a song one time and ...’” stretching out on a recording console, as Karlen wrote: “limbs awkwardly splayed like a body ready to be chalked by the coroner, he crossed his eyes and stuck his arm out.”

Which is pretty much what happened, give or take a few details.

And now, Neal has published a memoir, This Thing Called Life, a compulsively readable reconstruction of the relationship between the two Minneapolis natives, alternately middle-of-the-night confessional, hysterical, and athletic. “You want to play ping pong?” Prince would ask during lulls in the action. On one side of the ring was “the universally acclaimed genius” and “personification of hip” to whom other “intergalactic hipsters offered unashamed gush.” Prince was the “cultural icon who defied and cross-bred genres from fashion to funk … and whose death made the Eiffel Tower, the cover of the New Yorker, the front-page above-the-fold headline picture of the New York Times, and all of downtown Minneapolis glow purple.”

On the other, pencil ever behind his ear, was the “flamboyantly engaging” motor mouth, Brown graduate, and former bar mitzvah tutor (Hebrew name Natan Shmuel), whose Yiddish-speaking grandfather made Shabbos wine under special governmental dispensation during Prohibition for his local Minneapolis synagogue. As a special Christmas gesture, he carried Mason jars of the runoff—“let’s be honest, several illegal batches”—to neighbors in his mostly Black neighborhood of North Minneapolis. This earned him the moniker “the Wine Jew,” a designation that “guaranteed my grandmother and him, both octogenarian foreigners, safety and popularity in the neighborhood.” Years later, a check of his grandfather’s logs revealed that one regular recipient of the Yuletide wine was Prince’s father, John Nelson.

The magna carta of the tale is the initial RS interview, birthed out of the same sorts of betrayals, double-crosses, and acts of true faith that characterized post-WWII international agreements—and most of Prince’s life, which Karlen followed and participated in, to a degree, until the musician’s death from a fentanyl overdose five years ago today.

In the summer of 1985, Neal was already working on a story about Prince’s women—Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman—his musical collaborators and bandmates in The Revolution. Eager for a vehicle to promote his new album, Around the World in a Day, since he would not tour it, Prince had agreed to speak to Rolling Stone through Wendy and Lisa, and to appear on the cover with them. But the two apparently liked Neal and mentioned this to Susannah Melvoin, Wendy’s identical twin sister and Prince’s then fiancée, who apparently recommended that Prince come out of his cone of silence and speak as well.

And suddenly, the cover interview would feature the man himself.

“By recommending to Susannah Melvoin (and perhaps positing the idea to Prince personally) that the Little Big Man talk to me,” Neal writes, “Wendy and Lisa did the unthinkably generous: They gave up their own cover story. True, they would make it the following year [a story Neal also wrote], but they didn’t know that, and once you give up the cover of any major magazine, it’s always doubtful that the wheel will come around again. People in rock and roll just don’t give up being on the cover of Rolling Stone.”

Shockingly, not more than a year later, after the galaxy of hits that had put Prince and The Revolution on a par with the Beatles, Prince would disband the group, forever affecting his relationship with the two women. Yet Prince could also express unshakable loyalty. When Neal arrived in Minneapolis to meet Prince for the interview, he was shocked to learn that Rolling Stone planned to yank the rug out from under him and send the music editor to poach the blockbuster interview with Prince for himself. But Prince whispered nyet and shut that idea right down.

Neal wrote: “Prince lived a life where nobody—nobody!—knew more than 15 percent of what was going on in his life and brain. Still, that 15 percent could encompass a lot of surprises.”

For two days after Neal arrived for the interview, (“Just get enough,” Jann Wenner had told him, “that we can put ‘Prince Talks’ on the cover,”) Prince observed him, but wouldn’t speak to him. Neal gamely sweated out this further indignity, until, finally, Prince greeted the reporter and invited him to go for a spin in his car. Before turning on the ignition, Prince stared straight ahead through the windshield of his 1965 bone-white Thunderbird, murmuring, “I’m not used to this, I really thought I’d never do interviews again.”

Moved by the star’s anxiety, Neal left the tape recorder off and put his notebooks away. And as they drove through Minneapolis, and onto the empty field in Chanhassen on which Prince would raise Paisley Park, his future home and state-of-the-art recording studio, Neal apparently quieted Prince’s fears with his Marx Brothers bonhomie and his unusual interviewing technique: “I didn’t so much pose a query as begin babbling a run-on something that usually makes the subject interrupt me and say something just to get me to stop not making sense.”

This is how Neal talks, exactly as described but for one last thing. After the word salad ends, he squints at you, looking like he might bolt down a rabbit hole, but also a little judgy, like he wants to tell you there’s a piece of lint caught in your eyelash. Thoroughly, confusingly disarming.

And next thing he knew, Prince was driving Neal to his purple house and walking him through every room of the lakeside split-level.

“No, the man does not live in an armed fortress with only a food taster and wall-to-wall, life-size murals of Marilyn Monroe to talk to,” he wrote in the RS story, eager to dispel the recent account of a cocaine-addled former bodyguard who had spoken of such things to the National Enquirer. (Prince kept the man on his payroll and urged him to return to his job, saying he was sure the smutty paper had twisted his words.)

“If a real estate agent led a tour through Prince’s house,” Neal adjured, “one would guess that the current resident was, at most, a hip suburban surgeon who likes deep-pile carpeting.”

And in case you were wondering about the master bedroom of the man who had written and sung “Jack U Off,” “Head,” “Soft and Wet,” “Darling Nikki,” and, with “Sister,” “made the topic of incest danceable.” It was “nice … And normal. No torture devices or questionable appliances, not even a cigarette butt, beer tab, or tea bag in sight.”

Next stop was the heart of darkness itself. Astonishingly enough, considering his original trepidation about the interview, Prince decided to bring Neal to meet his father, John Rogers Nelson. It was his 69th birthday, and the old man wanted to play pool with his son to celebrate. As they approach, Neal sees him. “Relaxing against a tree was a man who indeed looked just like the perfectly, dapperly aged Cab Calloway in The Blues Brothers. Dressed in a crisp white suit, collar and tie, a trim and smiling John Nelson adjusted his best cufflinks and waved.”

Although it’s not generally accepted by the cognoscenti that the relationship between father and son shown in Purple Rain was autobiographical, and several details are clearly not true, such as the movie father’s shooting himself in the head, “Prince told me several times,” Neal writes, “without a detectable agenda for why he’d lie, that he and his mother had indeed been knocked about by Papa John.” And the only time Prince went off the record during the dozens of interviews that made up the first RS story, Prince said, “You can’t say that, that he hit me.” Prince told Neal that the fact that he didn’t try to run away from the beatings, or fight back, made him “feel weak.”

When he drank, Prince’s father developed an “apocalyptic rage,” in spite of his neighborhood image as the “coolest, smoothest, best-dressed cat in the surrounding blocks.” And although Prince later engineered a public relations campaign to the contrary, “John Nelson drank.”

“Smack, Smack” and “... baby starts to cry/Please don’t lock me up again, without a reason why,” are not the most hair-raising lyrics Prince sings in “Papa,” the fifth cut on his 1994 album Come. Karlen writes:

John Nelson heaped physical abuse on his wife and child whenever he felt they impinged on his personal space by, in Prince’s case, trying to sneak a few scales on John’s off-limits piano; or, increasingly with [wife] Mattie, whenever she breathed her husband’s air or asked him a question.

“The Fabulous Prince Rogers” was the name Nelson gave himself when pretending to be a jazz man on the order of Thelonious Monk, but who in truth didn’t have a shadow of the chops or the talent. In fact, he had a stifling day job at Honeywell, and blew the family’s food money on women and sharp clothes for his night avocation—playing bump-and-grind honkytonk in a sleazy strip joint on Minneapolis’ Hennepin Avenue. Neal’s great uncle Augie owned the joint that was “one of John Nelson’s most frequent employers during the years Prince Rogers labored under the delusion that he was a historic jazz figure who’d so far just lacked the requisite break.” A watering hole where hoodlums of various stripes gathered with celebrities, comedians, and politicians—Jimmy Hoffa, Henny Youngman, John Dillinger, and Lenny Bruce among them—it offered no opportunity for Nelson to experiment with his own compositions, which he claimed were “ahead of their time.” He was simply required to play the basic accompaniment for the “peelers,” as they were called.

“Footage from A Current Affair provides perhaps the best-recorded proof that exists of just what an asshole John Nelson was,” Neal writes. “Sitting at a piano for one piece of the segment, John’s wrists wander up and down the keyboard in a cacophony of nothingness, then slide into ‘Purple Rain,’ purporting to show the direct influence he’d had on the song, which he ‘demonstrated’ that he essentially wrote.”

Nelson told Neal a few years later:

Prince says I gave him my name out of spite, as a curse, for him being born and taking away my career, while he got the life that was to be mine. He’s wrong. That name “Prince Rogers”—that was a blessing, a blessing from God. I gave that blessing to Prince, so he achieved what I myself was never given the chance to achieve.

Prince clarified: “He didn’t tell you he took the name ‘Prince’ off a dog he once knew—a dog he didn’t even like?”

It’s hard for a child not to turn his or her father into a hero, and sadly for Prince and his overcharged psyche, “between a third and half the time … Prince refused to second the motion that his father was a wretched reptile. At those times his father, Prince thought, was more than a great talent unto himself. Prince also thought he himself was his father. ‘Me and my father, we’re one and the same,’ he said in 1985. ‘My father’s a little sick, just like I am.’”

“Prince was the best of sons; Prince was the worst of sons,” Neal writes. “Either way, it was heartbreaking to watch. I knew the first entire day I spent with Prince, which included a half-day spent with Prince’s father, that John Nelson had long since killed off his son.”

How did he really feel? “My impressions … providing narration to his noxious aura from the second I met him? As Mike Tyson, former heavyweight boxing champion of the world and convicted rapist, said of Don King, his former manager who’d once kicked a man to death on the streets of Cleveland: ‘He’s a wretched, slimy, reptilian motherfucker.’”

“With all due respect.”

The same forces that broke Prince as a human being gave him the fire to take his talents to another world (his favorite movie was The Idolmaker.) Prince signed his first contract with Warner Bros. Records in 1977 while still a teenager, and he fought for the right to produce the record himself. He also played all 20 instruments on the disc, not to mention, as recorded in the liner notes, “all vocals.” The instruments he played on that record are “electric guitar, acoustic guitar, bass, bass synth, singing bass, fuzz bass, electric piano, acoustic piano, mini-Moog, poly-Moog, Arp String Ensemble, Arp Pro Soloist, Oberheim four-voice, clavinet, drums, syndrums, water drums, slapsticks, bongos, congas, finger cymbals, wind chimes, orchestral bells, woodblocks, brush trap, tree bell, hand claps, and finger snaps.”

Neal asks: “How in Minneapolis does a teenage African American male even learn the clavinet? For that matter, what is a clavinet?”

Prince was lucky enough that Mo Ostin, chairman of Warner Bros. Records, and Lenny Waronker, president of Warner Bros. Records, believed in following their guts. Moreover, Ostin’s general plan at the time was, according to music writer Robert Lloyd, to “sign the original and most extreme exemplar of any contemporary trend.”

Prince, as he would inform Neal, already had a “highly honed notion of the righteousness” of his own contemporary trend. He called it “sick.”

Prince cued up the tape of the just-released “Raspberry Beret” video to explain the concept. “The pretty-as-peonies song begins with Prince clearing his throat in a prolonged guttural rasp of the kind I emit when forced to eat mayonnaise.” He asks Prince why he did it.

“That’s it, that’s what I’m talking about,” Prince told him. “I just did it to be sick, to do something no one else would do.”

Prince took a moment to get the words right. “A lot of my peers make remarks about us doing silly things onstage and on records. They don’t understand the simple idea of sick.”

Neal asked: “What kind of silliness, exactly?”

“‘Everything,’ Prince said: ‘The music, the dances, the lyrics. What they fail to realize is that is exactly what we want to do. It’s not silliness, it’s sickness. Sickness is just slang for doing things somebody else wouldn’t do.’”

Prince was a genius, with his own vocabulary, aesthetic, and philosophy. But he also lied, telling stories about himself and his family for the sheer purpose of confounding everyone. He said he did so to throw reporters off the scent, so they would focus on his music and not the fact he came from a “broken family.”

To Neal, “he was the mere but reassuringly human man behind the curtain in The Wizard of Oz, pulling the levers to make impossible visions—but so painfully human one felt embarrassed for him when the curtain was pulled back to reveal the reveal. When people asked what Prince was like, I always said: ‘He was the loneliest person I ever knew.’”

But Prince craved solitude. When planning Paisley Park, he imagined it as a “place in your heart where you can go to be alone.” Neal compares Prince’s desire to hide to that of other geniuses, like James Brown, who was famously “foggy” about his past, and to Emily Dickinson, who tried to disappear in plain sight as a master of “covering her own tracks.”

One matter that caught Prince’s early attention and possibly earned his lifelong affection was the embarrassing fact that Neal fell asleep on him in the middle of one of those first interviews.

“Mamma jamma, you listening to me?” Prince asked, looking over to the passenger seat at Neal, whose attention, he sensed, was lagging. Mamma jamma was the jive word Prince was (unsuccessfully) utilizing to try to wean himself off of his other favorite word, motherfucker, now that he was considering it a good commercial idea to clean up his speech.

Neal, exhausted by the stress of the assignment and staying up all night with Prince, tried to find a second wind as he looked out the passenger window at all the familiar sights of the neighborhood. “That’s where my grandparents lived,” he told Prince. “Right there … A few blocks up on Plymouth.”

“What them old Jews, your grandparents, doing staying here North?” Prince asked. And Neal explained that after the seven summer riots of the 1960s had chased away most of the white people from the neighborhood, his grandparents had stayed in their “pleasantly peasant-size, spackled gingerbread house” on Oliver Avenue North.

Neal explained that his grandmother had said, according to his father’s translation from the Yiddish, “I walked across Russia to get here, and I’m not moving. We stop here.”

But Prince was more interested, astonished really, at catching Neal falling asleep before his very eyes, even momentarily.

Karlen, dragging himself out of his exhaustion, said, “We’re off the record now anyway.”

Prince: “You said that, not me.”

“I got what I needed. I got much more than I needed.” Karlen was talking about the RS interview, the anxiety about which was now blessedly draining from his nerves.

“They wanted to give you up, get their music editor to be you,” Prince said, laughing. “Everyone dying to hear me talk, and you falling asleep on me.”

“I was resting my eyes … So maybe I did fall asleep while the world’s biggest rock star was talking.”

‘“Man, you gotta wake up!’ Prince had commanded. ‘You know how many lives God gives you?”’

Prince alluded to an early death way back in 1985. ‘“Sometimes I’d be onstage and [feel] a little tired and run down, like maybe I wasn’t going to make it,’ he said back then, so softly you could hear a heart break. ‘I would hurt myself,’ he continued, ‘like I’d hit my arm with my guitar, or slide down the pole the wrong way and twist an ankle or something … I was afraid that I could kill myself out there, and nobody would notice.’”

Hearing this, Neal tried to make him laugh by sending him a copy of Dorothy Parker’s famous “Resumé.” He mailed The Portable Dorothy Parker to Paisley Park, “bookmarked at the mordant poem” in which Parker “enumerates how guns are against the law, the rope used to hang yourself could break; and gassing yourself would give off a terrible stink. She concluded: ‘You might as well live.”’

Prince memorized the poem.

By his account, Neal gave or lent Prince about a dozen other books over the years. Prince had “loved” David Simon’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, in which the author had followed homicide detectives for a year, awakening Prince “to the problems of Baltimore” about which, in response to the death of Freddy Gray in police custody in 2015, he’d written a song, “Baltimore.” Neal also gave him books about con men, a favorite subject of both, including The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man, a “classic 1940 sociological study of the art, science, and conscience behind the grift,” as well as “Yellow Kid” Weil: The Autobiography of America’s Master Swindler, the 1948 book that inspired the film The Sting. Neal also sent him Machiavelli’s The Prince, and, “to satiate his interest in golems, dybbuks, and the Kabbalah,” he sent him Joshua Trachtenberg’s Jewish Magic and Superstition, a 2013 reprint of “the 1939 classic that included incantations to make your own golem.”

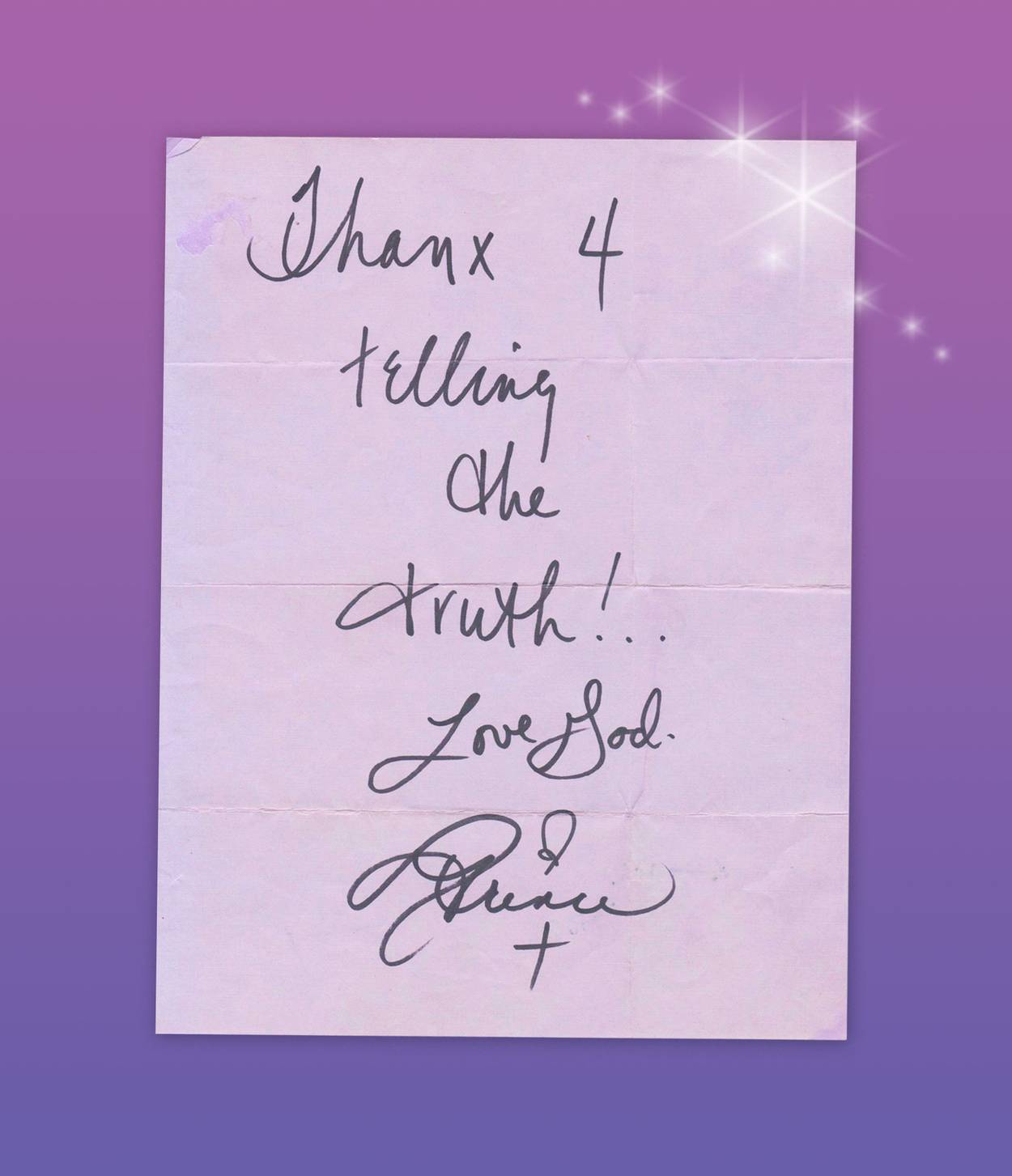

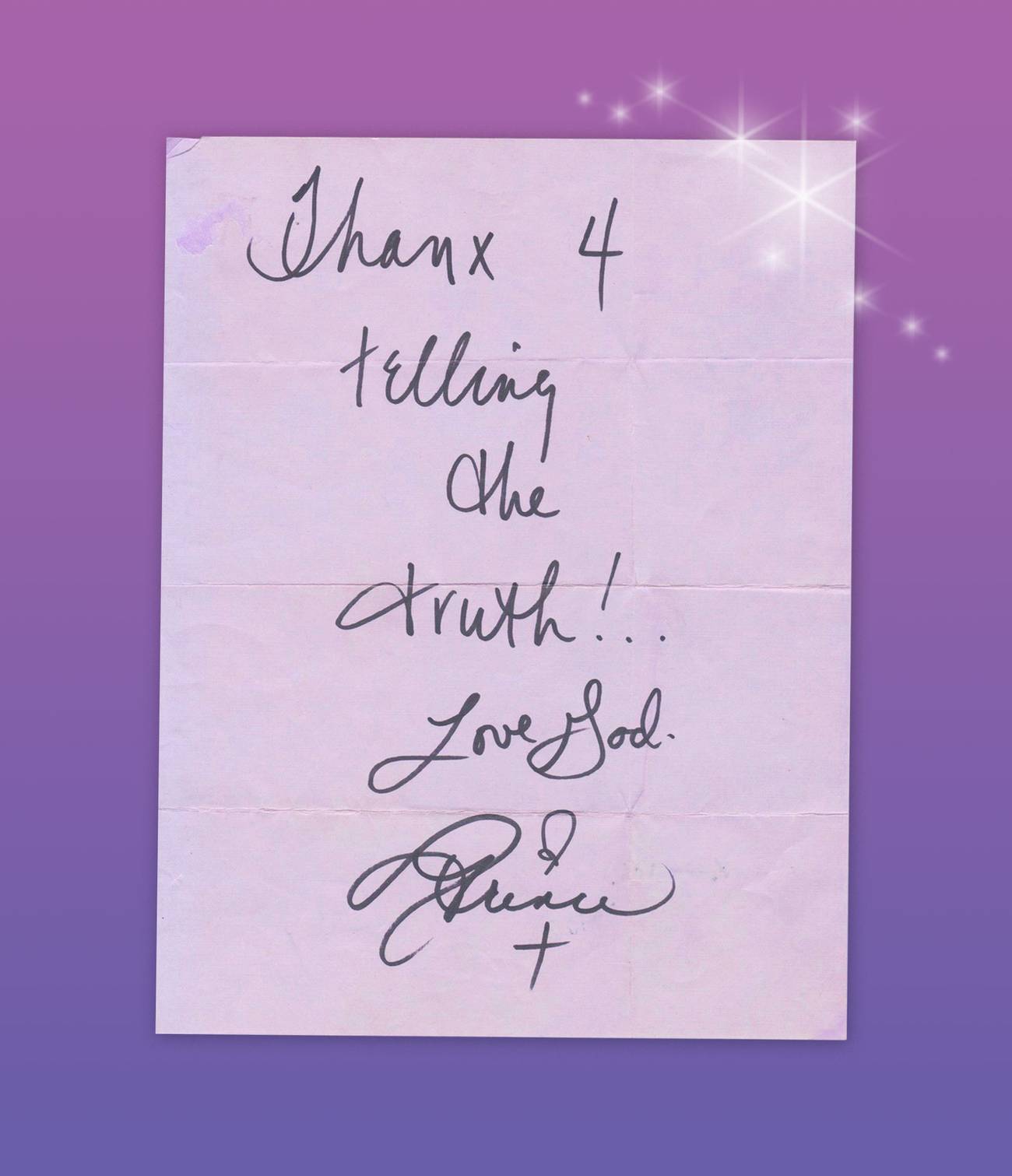

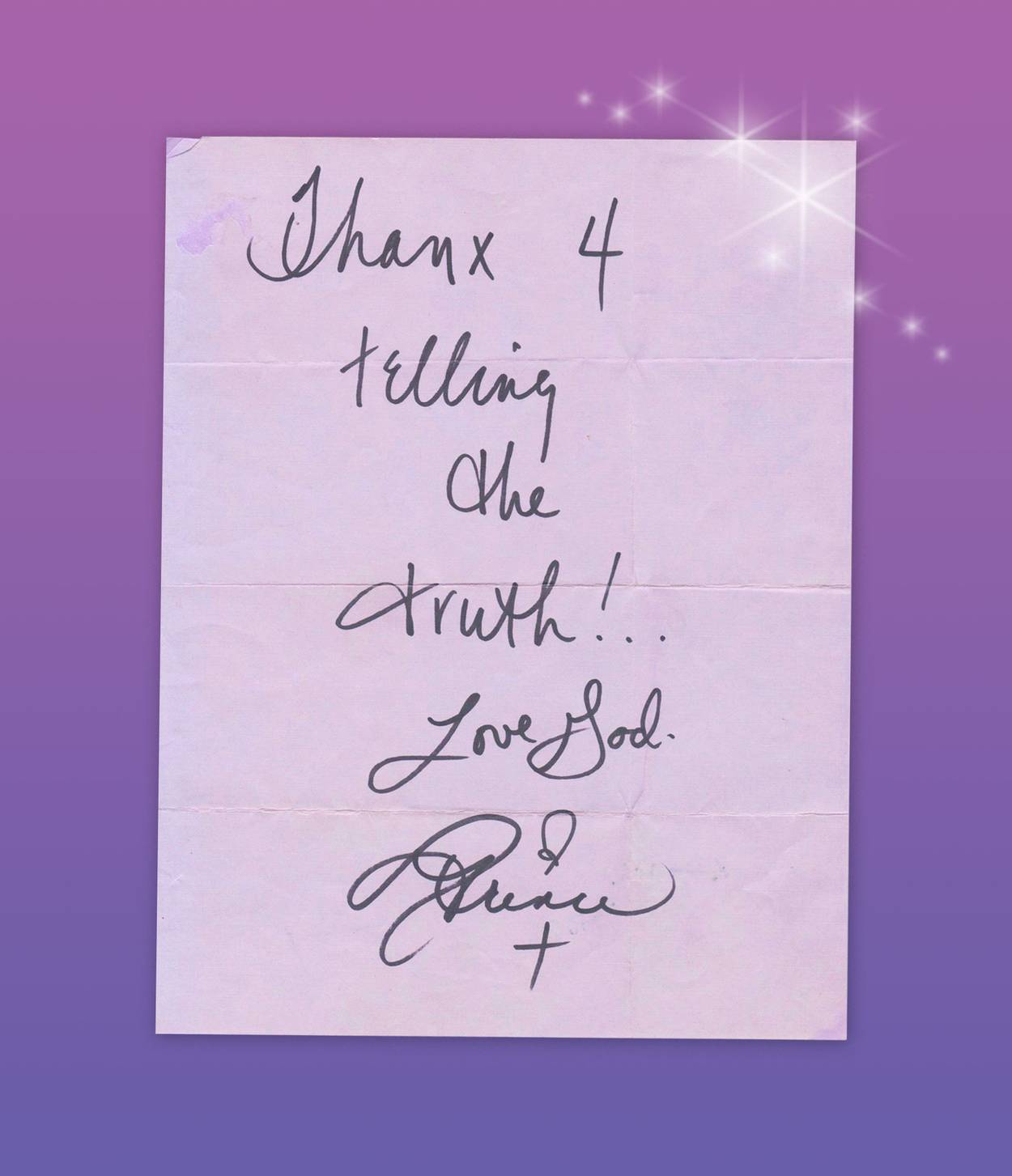

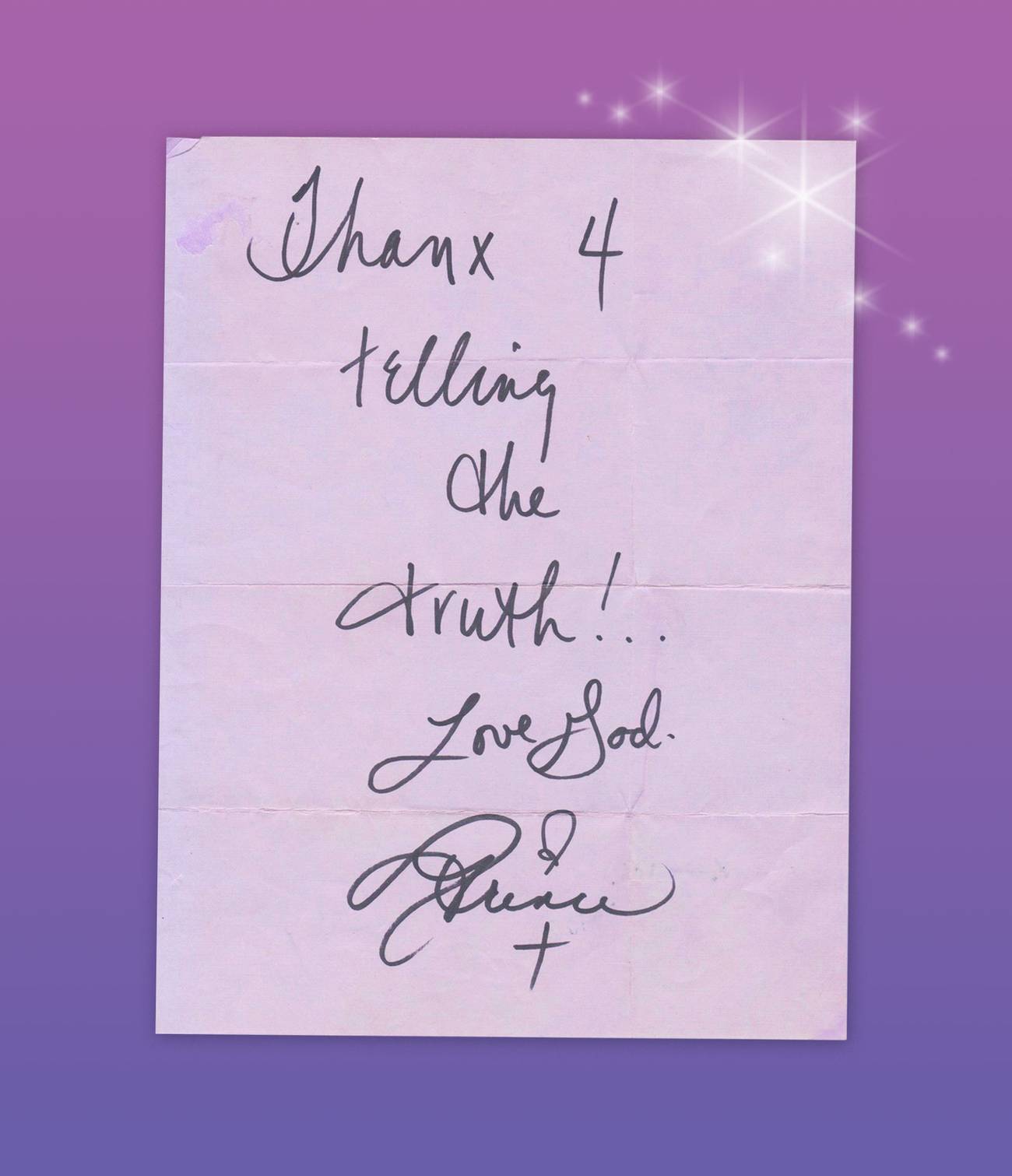

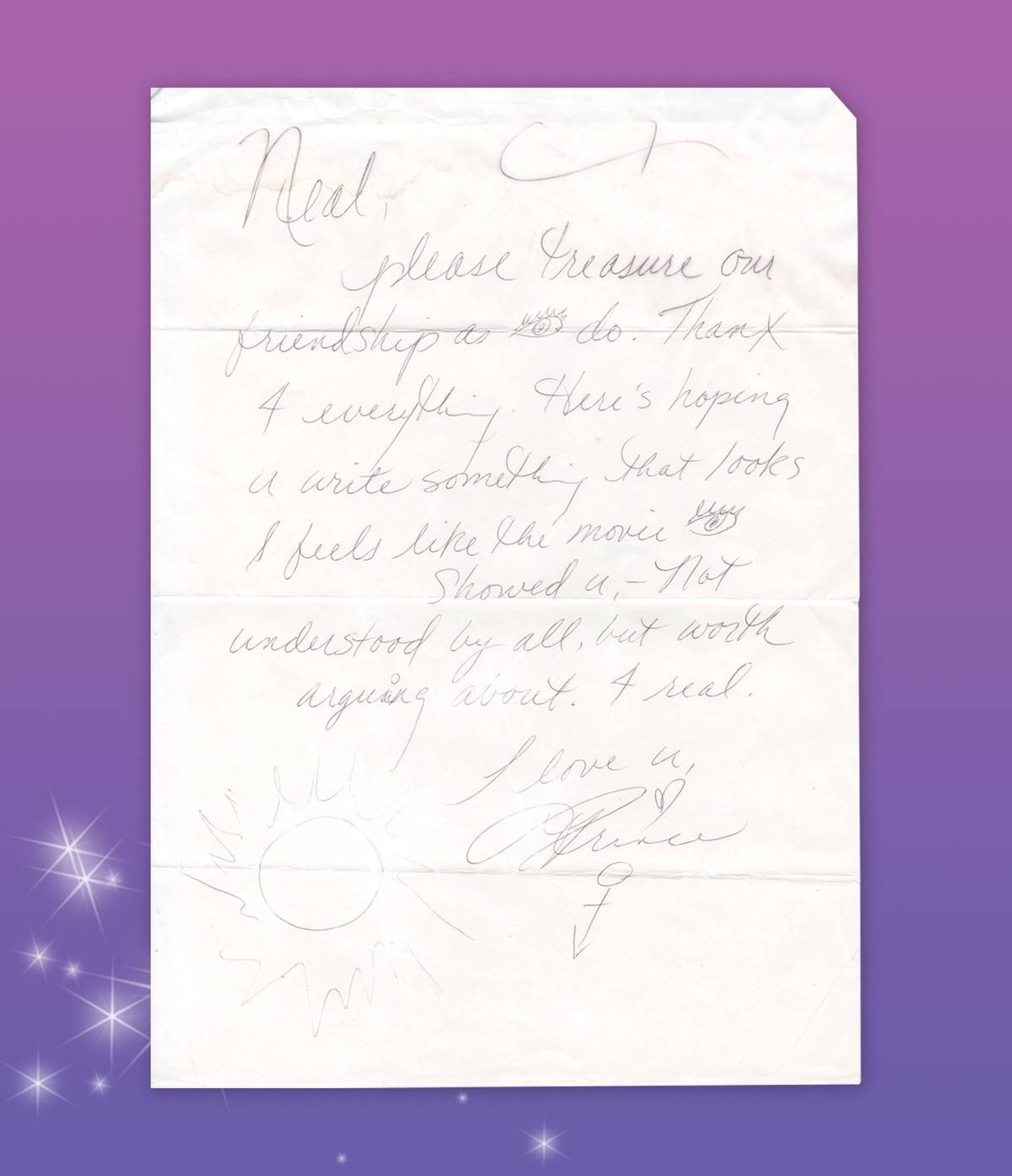

After the 1985 RS story came out, Prince sent Karlen a note: “Thanks 4 telling the truth! Love, God, Prince.” Neal put the note into a little frame and hung it up over his desk. Thirty-four years later, Susannah Melvoin told Neal, “You were the only reporter who made Prince sound like he really sounded.”

Neal remained the only reporter whom Prince would allow to record or take notes during interviews.

Until he wasn’t. Rolling Stone shelled out thousands of dollars to fly Neal to Paris and Switzerland to follow Prince for weeks on his 1990 Nude tour. Five seconds before their interview was to begin, Prince told him he couldn’t record or take notes of their conversations. “I knew he was fucking with me, but it wasn’t funny.”

Neal drank copious amounts of liquid and feigned a bladder problem while running off to the loo to scribble down notes on toilet paper and stuff them in his clothes. And Prince knew exactly what was going on, Neal “stealing off to the bathroom every five minutes to take notes, hour after hour, interview after interview, and it had all felt a little sadistic.”

After finishing the piece, Karlen never wrote about him again. “I didn’t quit Prince, I just quit writing about him or hanging around his world,” he writes. He was sick of celebrity journalism and wanted to strike out and do other things. (He has written eight other books.)

But they stayed in touch.

“Sometimes we talked on the phone several times a year in the middle of the night for between several minutes and several hours. Sometimes I got letters, sometimes on purple stationery. Two of the eight times I published what I thought were ‘real’ books, I received anonymous purple flowers. Over thirty-one years I’d guess we saw each other in preparation for published profiles on a couple of dozen occasions, saw each other socially thirty or thirty-five times, and talked on the phone a few hundred times in the middle of the night. About fifty unanswered (or unheard) calls from an ‘unknown’ number registered on my phone during the hours when only Prince would call.”

For his own reasons, during Prince’s lifetime, Neal could never bring himself to call Prince a friend. In part, he was allergic to getting caught up in Prince’s florid act. He also was determined to resist the self-inflation often visited on celebrity journalists. Yet, following the paralyzing grief that organized a surprise attack on him after Prince’s death, and continuing through the writing of the book, he has come to understand otherwise. Another letter from Prince shares pride of place over his desk. It reads: “Neal, please treasure our friendship as I do”—he drew an eye for an “I”— “4 real. I love u.”

Emily Benedek has written for Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and Mosaic, among other publications. She is the author of five books.