Through the Lens of Nissim Levis

An exhibit of stereoscopic photographs portrays a rarefied vision of Greek Jewish life, almost entirely wiped out in World War II

As a little girl in Ioannina, a city in northwestern Greece, Zanet Battinou recalls her grandmother speaking in hushed tones of the prominent 19th-century Jewish patriarch, Davidson Effendi Levis. “My grandmother was one of the older women of Ioannina to survive the war, so she remembered him,” said Battinou, now director of the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens, where we were seated on a recent morning. Their two families, like many in Ioannina, were Romaniote Jews, neither Ashkenazi nor Sephardic, but descended from Hellenic communities established around the third century BCE. “He was an important man,” Battinou remembers her grandmother telling her, “the head of a big family of notables and philanthropists.”

A photographic portrait of the fez-wearing banker and businessman—one of only four Jews elected to the short-lived Ottoman parliament of 1877—was hanging nearby, alongside a family tree displaying his and his wife Hannoula’s many descendants. Pinned to the photograph were family heirlooms, medals its subject had earned for his service, not only to the Ottoman Empire, but also to Greece, France, and Austria-Hungary.

Yet it was not Davidson Effendi’s many accomplishments, but rather, a hobby pursued by his son Nissim, that had brought us to the museum that day. Born in 1875, the fifth of six children, Nissim Levis was educated in Switzerland and trained as a doctor in Montpellier and Paris before returning around 1904 to Ioannina to practice, opening an office where he often treated patients for free. A handsome, mustachioed sophisticate, he was passionately interested in new technologies; his leisure pursuits included photography and automobile racing. He was affiliated with various women and enjoyed the companionship of at least one close, long-term male friend, but he never married and left no descendants.

What he left instead—before Nazi occupiers murdered 92 percent of Ioannina’s Jewish population, including Nissim, then age 69, and other Levis family members—were over 550 pair of glass negatives, the fruit of his passion for and skill with stereoscopic photography. He took pictures both at home and during his studies abroad and travels to France, Italy, and Switzerland, to the Ottoman capital of Istanbul (then called Constantinople) and to Izmir.

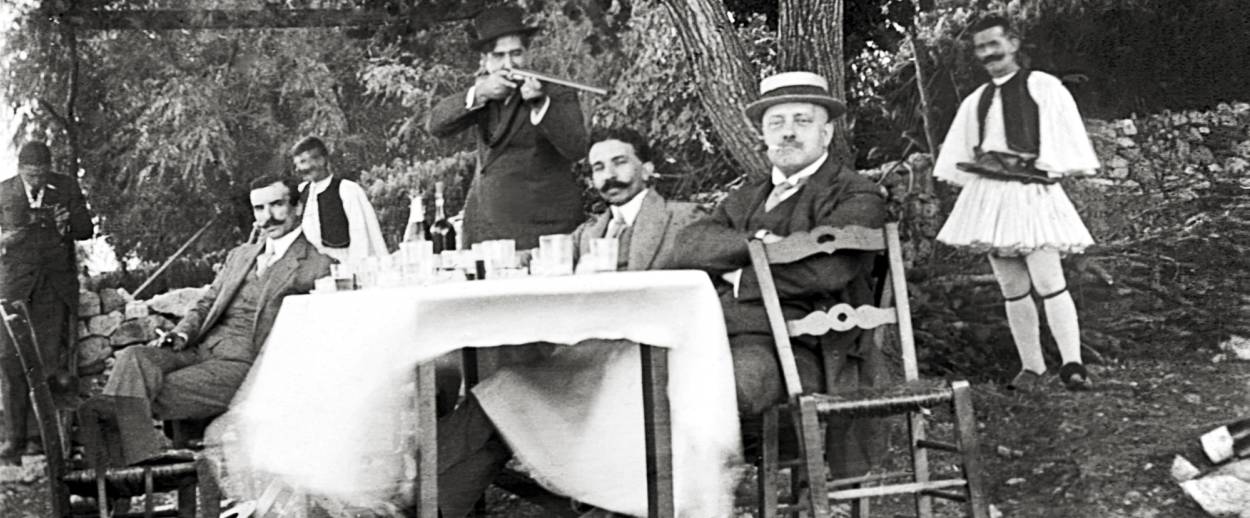

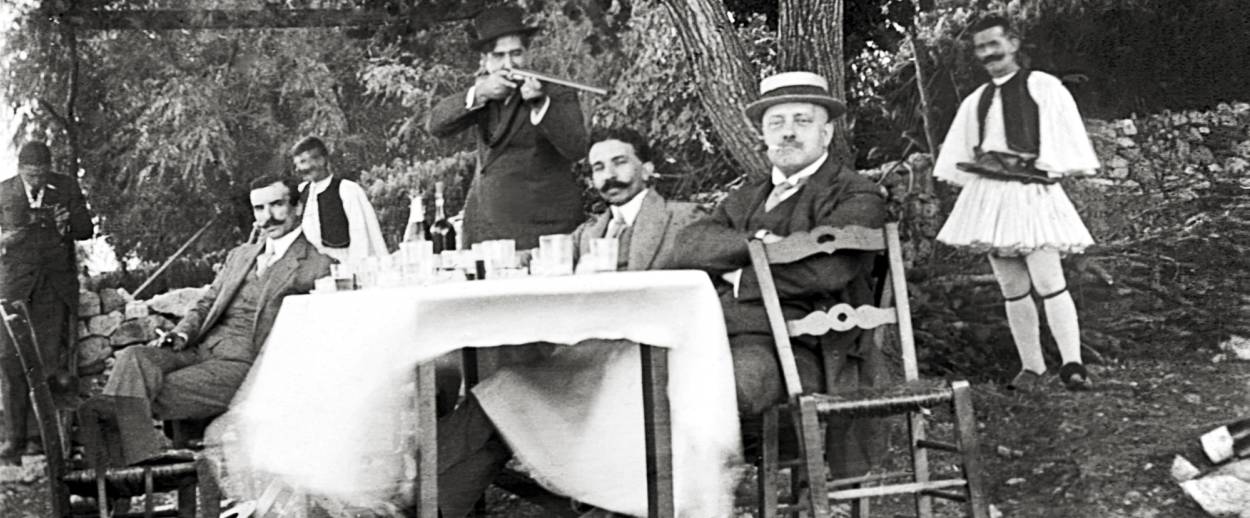

Through the Lens of Nissim Levis: A Family, an Era, a multimedia presentation closing today after a year run at the Jewish Museum of Greece, showcased this remarkable body of work. Among Nissim’s earliest photographs are pictures of fin de siècle medical intern life and high jinks in Paris, but laced (like the novels of French Sephardic author Albert Cohen, a Levis family friend) with a certain “Oriental” flair. He shows himself dressed up as a pasha, for example, for the interns’ annual masked ball, reclining on embroidered silk cushions brought from Ioannina. He photographs children—including one kaffiyeh-clad boy—sailing toy boats in the Luxembourg Gardens, or his friends playing whist and reading newspapers at the elegant Café Soufflot, a popular Left Bank hangout for expatriates, including members of the Young Turks movement. Other pictures—of top-hatted, fan-wielding crowds watching the races at Longchamp or returning via horse-drawn carriage from the Bastille Day parade on the Champs Elysées—reflect a fascination with speed and motion, reminiscent of his near-contemporary Jacques-Henri Lartigue.

But life at home under the Ottoman Empire also captured his attention. Back in Ioannina, he records outings on Lake Pamvotida to hunt waterfowl and promenades en famille (the women bearing parasols, the little boys in sailor suits) on the picturesque, abandoned island at the lake’s center. A devoted uncle, he notes with pride the engagements of his nieces, handsome young women displaying their copious dowries, and their weddings, when guests pack the town’s main street, which runs between the two Levis family mansions, as far as the eye can see. And he portrays their growing families.

Ottoman rule in Ioannina ended with the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913. Among Nissim’s many photographs of historic events is the picture he shot from a high clock tower of the victorious Greek cavalry entering the city, and the crowds awaiting them.

After that, the Levis family men stop wearing the Ottoman fez; many adopting straw boaters instead. The younger women gradually trade their mutton-sleeve gowns and feathered hats for drop-waist sheaths and cloches. The arduous trip from Ioannina to Western Europe—by horse or mule through the rough Epirus mountains, then by boat and train—becomes (for the lucky few to make the journey) a bit easier, though automobile mishaps are still common. The men of Nissim’s generation, including his brother Maurice, an inventor whom he visits repeatedly in Marseilles and Paris, take on weight and gravitas. There is Alpine hiking and cavorting amid the ruins of the Acropolis with his grandnieces, and the occasional family sojourn at a French Grand Hôtel.

But nothing changes all that much, in the pictures at least. Nothing seems to perturb the sense of optimism and belonging, the solidly bourgeois faith in progress, that decades earlier had led Nissim, as a young medical intern, to breathlessly chronicle the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The fairy-tale-like turrets and spires of its Palace of Electricity, its moving sidewalk, its exotic international pavilions lining the Seine, all appear to promise a cosmopolitan future of unlimited horizons.

The pictures become more rare around 1930. Photographic materials, which Nissim had imported (most likely from France) became harder to procure. Money was scarcer, borders were tightening; the distant rumblings of war would soon be audible.

And we know how this story will end. The Nissim Levis Panorama: 1898-1944—a catalog compiled by Alexander Moissis, whose great-grandmother was one of Nissim’s beloved nieces—ends with a photograph dated March 25, 1944. It shows men, women, and children, bearing bundles and boarding a truck parked just down the street from the Levis family homes. Nissim Levis didn’t take the picture; he was among the Jews deported that morning. He and his relatives were taken by truck to Larissa and loaded onto a train; a few days later those who survived the journey were murdered at Auschwitz.

The catalog, with an introduction by Columbia University historian Mark Mazower, also tells the story of the photographs’ rediscovery, once the world they depicted had vanished for good. After the war, Nissim’s grandniece, Hiette (who had escaped deportation by hiding out in Athens) returned with her husband to Ioannina, to find the family homes looted and burnt. Nothing of their past life, it seemed, had escaped the war’s devastation. But walking back to their hotel, they came upon a young boy, a street vendor selling “Views of the panorama!” for one drachma. Approaching him, they recognized their uncle Nissim’s stereoscopic viewfinder and his glass negatives. They bought the lot and began the decades-long hunt, here and there and in the flea markets of Athens, to collect as many of Nissim’s images as possible.

In Athens, the tiny Romaniote synagogue, called The Tree of Life (Etz Haim)—tucked away behind a courtyard where a centuries-old palm tree towers—is now only open for High Holiday services and special occasions. Its congregants, many of them aged, gather on Saturdays across the street at the city’s main synagogue, Beit Shalom.

Unannounced, my family joined them there for the close of Shabbat one Saturday evening. My teenage son was given an aliyah, and after services we sat with the congregants, a handful of elderly men, a married couple (Israeli tourists), and the young chief rabbi of Athens, Gabriel Negrin, who shares my paternal grandmother’s maiden name. In fact, I learned while writing this story that my grandmother, who died long before I was born and whom I had always assumed was Sephardic, was, in fact, a Romaniote Jew from Thessaloniki. (She had married into my grandfather’s large Sephardic family.) So the past yields its secrets slowly, if at all—a puzzle whose outlines we perceive but dimly.

For Greek Jews, Thessaloniki is, to a great extent, a missing piece of the puzzle. There, the death toll for the Jewish community during the war was even higher than in Ioannina—over 96 percent—and the Nazi looting of Jewish artifacts was far more extensive. “There were 16 synagogues in Thessaloniki, there were religious schools, rabbinical schools, homes, libraries,” Zanet Battinou explained, “but despite all that, there is very little from Thessaloniki in our collection.” The museum has been vigilant, but little has turned up. “I think all those looted items are together somewhere,” Battinou said ruefully, “though that somewhere could be at the bottom of a lake.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Leslie Camhi’s first-person essays and writings on art, photography, film, design, fashion, and women’s lives, have appeared in the New York Times, Vogue Magazine, and many other publications.

Leslie Camhi’s first-person essays and writings on art, photography, film, design, fashion, and women’s lives, have appeared in The New York Times, Vogue Magazine, and many other publications. Her translation from the French of Violaine Huisman’s award-winning debut novel, The Book of Mother, was published this month by Scribner. She’s on Twitter @CamhiLeslie and on Instagram @drlesliecamhi.