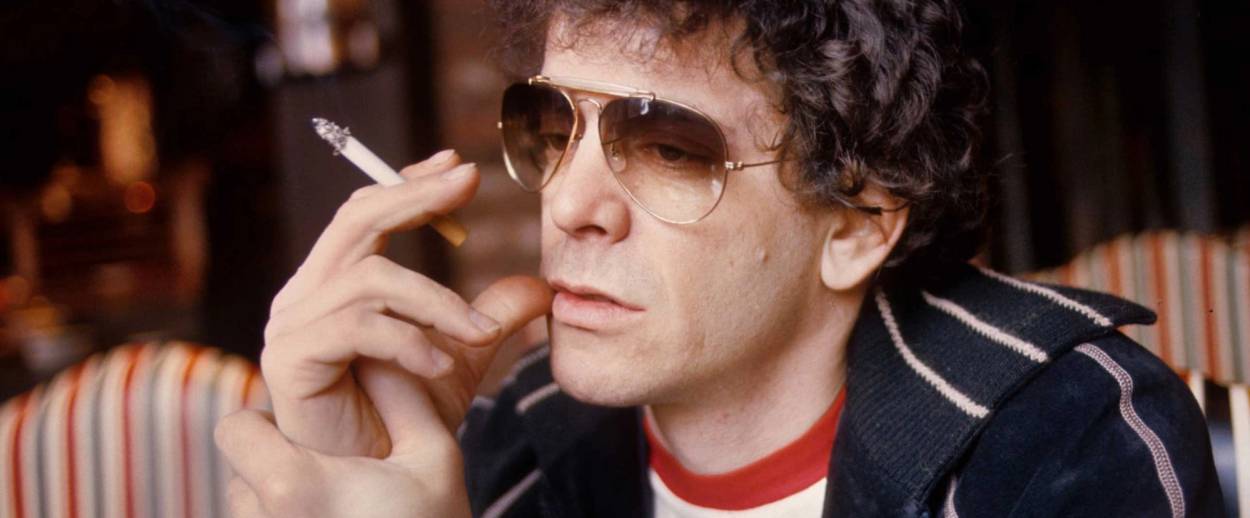

No Mr. Nice Guy: Lou Reed

On the late Lou Reed’s 69th birthday, Elizabeth Wurtzel explained that contrary to the assertions of Philip Roth and others, the problem with Jewish male artists is not that they are too nice

This piece was originally published on March 2, 2011, Lou Reed’s 69th birthday. The musician died Sunday.

I want to wish Lou Reed a happy birthday, but first I want to tell you a story that says something important, albeit indirect, about Lou’s life and his career, and the fact that he is such a legendary asshole. So please bear with me.

While I was living in New Haven a few years ago, I made plans to meet a high-reward, high-maintenance friend halfway at a Bruce Springsteen concert in Bridgeport. It soon became clear that this plan had all the charm of being inconvenient for both of us, and in a hateful place. My friend—I’ll call her Daphne, because that is her name—enlisted her brother to drive to the venue, and it was a great concert: This was during a time that Bruce was closing shows with an apocalyptic, prophetic version of Alan Vega’s “Dream Baby Dream.” After the show, Daphne and I went backstage, and for reasons that escape me, her brother went to move the car, which was ill-advised as there was no way he could get past security without me. Anyway, to bring this on home, we’d been chatting with the Boss for at least 45 minutes, he was telling us about how Philip Roth is his favorite author, and somehow Daphne’s lingering sibling comes up. So we reveal to a very astonished Bruce Springsteen that Daphne’s brother is somewhere in the parking lot waiting for us.

So here’s the takeaway: Bruce is gob-smacked that we have left this poor, lost brother somewhere out there, even though, truth be known, Daphne has issues with anyone she’s related to (and anyone she’s not related to, including people she’s never met), and her brother’s lonely parking lot exile is completely fine with her, I think, and possibly even a desirable thing. In any case, Bruce gets up off the couch, leaves the building, and goes and finds Daphne’s brother, and brings him back to his dressing room.

Now let me make this clear—I’ll even put it in Passover terms: It was Bruce himself and not an angel of Bruce who went looking for the errant brother, even though factotums and minions were here there and everywhere, and could easily have been dispatched.

I really don’t know why Bruce was so kind in this way to Daphne’s brother, who he did not even know, but this story is consistent with others that you’ll hear from almost anybody. People who live in Monmouth County who have been picked up in the Springsteenmobile while hitchhiking, and that sort of thing, is the most common version of this story. I’ve been bringing friends backstage with me to meet Bruce for maybe 15 years now, and he remembers names, he remembers their brothers-in-laws’ names when he signs autographs. He’s a hopeless mensch.

Bruce Springsteen really got any creative person’s dream career, and his good-heartedness and good-spiritedness are part of it: both because it made the people behind the scenes want to do their jobs that much better, but it also means that he connects with an audience in a way that holds them close. Is he really cool? No, of course not. I’m a huge Springsteen fan, and yet if either he or Bob Dylan had to be erased from the world’s hard drive, I would save Bob Dylan’s work for sure—he’s the greater talent, and by leaps and bounds and skyscrapers and rocket blasts. But Bob Dylan is an alien to his public. He’s disconnected and distant in a way that Bruce is present and close, which is, in itself, a talent.

All of this leads me to the strange case of Lou Reed, who makes Bob Dylan look like Will Rogers. Bruce Springsteen, with his good manners and total decency is kind of the nice Jewish boy that Lou Reed—and, of course, Robert Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota—ought to be. Which seems counterintuitive—after all, Lou Reed and Bob Dylan are Jewish, and according to Philip Roth (Bruce’s favorite author after all), the hardest thing for a Jewish boy to be is bad, and yet they are both legendarily unpleasant people.

But you know what? The anecdotal evidence—at least among our artistic icons—suggests that Roth got it wrong. I mean, Norman Mailer was not just a wife-stabbing wretch himself—he actually helped get another wretch out of jail to murder again. Woody Allen’s heart wants what it wants and … oh boy. Roman Polanski—dear me. Leonard Cohen—does he seem nice to you? Never mind Roth himself, who both bears witness against himself and has Claire Bloom and others to corroborate his self-accusations.

So all I can say is: What the fuck was Philip Roth talking about? Yes, yes: I know—the CPA who lives in a split-level in Demarest, New Jersey. All the same, as public figures expressing the notion of Jewish identity—or denying their Jewishness altogether, which is of course the most Jewish thing you can do—the creative Jewish man isn’t very nice at all. In fact, he has been an absolute dick.

To get back to the contrary and instructive example of Bruce Springsteen, playing the role of the Christian character known as the Good Samaritan—what could be less Jewish? All that good-natured generosity is way too open-hearted and even obsequious, it lacks the judgmental prickliness that makes Jews so picky and stingy with their love of human beings, despite a huge and unbridled passion for humanity. In any case, this is the best I can do by way of giving an ethnocentric explanation for the fact that I am trying to write a heartfelt tribute to Lou Reed on the occasion of his 69th birthday, and I can hardly find a soul alive who doesn’t have an unpleasant story to tell about some chance encounter that they had with Lou Reed.

If, like me, you happen to be a native New Yorker, there is a good chance that you take Lou Reed’s presence for granted, like the woman you see almost every day walking her Pomeranian when you are out strolling with your dog: He really lives here, he takes the number 1 train, he sees documentaries about R. Crumb at the Film Forum. The only other celebrity who comes close to being as present within the municipal bloodstream is Ethan Hawke, who proves Kurt Vonnegut was right when he said we are what we pretend to be, because Lou Reed has cultivated ordinary-creative-person-ness with such botanical intensity that it’s become who he is. And so it is, with Lou Reed living among us for many years with his wife Sylvia on West End Avenue opposite the Calhoun School, and now with Laurie Anderson on West 10th Street. An unusual number of people have had chance encounters with him, and apparently it’s been universally unfun.

Lou Reed stories are the opposite of Bruce Springsteen stories. No one’s brother-in-law is ever rescued from a parking lot and treated like a king. The pedestrian admirer or the average autograph desirer is greeted with derisive hostility, with the precise prototype of the punk-rock sneer that has made Lou Reed the precise prototype of the sneering punk-rocker. I remember buying a vinyl version of Live In Italy when I was in high school and getting into the 79th Street subway station on Broadway to be greeted by none other than Mr. Reed, who looked like none other than Robert Plant. Of course I was completely excited by the coincidence. It’s not like I’d bought something common like the first Velvets’ LP or something obvious like Transformer—and I was certain he’d be moved by my fanaticism. I started jumping up and down—I really was jumping up and down—and telling him to look and see what I had, which was no doubt annoying, but still, this was long before the reissue of all the Velvets’ stuff, no one cared about Lou Reed unless he/she was also claiming to be named Holly from Miami, and I was a teenager. Instead of responding, Lou Reed walked away and started kicking the tiled wall at the platform where people waited for the IRT, to show his displeasure with my enthusiasm for his work.

After that I learned my lesson. Many years later, I had an experience that might have been phenomenal if I hadn’t thought better of it at the time. At either the behest or the request of an editor I cared about, some time not long after the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, I was drinking at the legendary Lion’s Head in Sheridan Square with a young painter who had never been out of East Berlin. I don’t mean that he’d never been out of East Germany—for whatever reason, he had never even ventured beyond city limits, which he explained was strangely common in iron-curtain Europe. Somehow I asked who he’d most like to meet in New York City, and he said that the album Berlin had sustained his cohort for so many years, because it was the only way any of them know that anyone on the other side of the wall knew or cared that they were alive. Of course, the funny part about that album is that when it was made in 1973, Lou Reed had himself never been to Berlin, it was about an idea. And I remember sitting and thinking how great it was that this German guy’s misunderstanding—his idea—about someone else’s understanding—his idea—had such great force. And somewhere between thought and expression—go ahead, assume that I’m lying, if I were you I would—into the bar walks Lou Reed himself. If this were a movie, only no screenwriter trying to maintain anything like verisimilitude would put such an absurdity into a script.

Here’s the takeaway: Despite what has to be called a miracle—I will not call it a coincidence, because this was all too much—I did not get up from my barstool to walk over to Lou’s frosty gulag archipelago on the other side of the Lion’s Head. Even the potential for great beauty—it would have been pretty great, and maybe life-alteringly amazing—wasn’t worth what my cost-benefit analysis told me was a more likely outcome of pedestrian unpleasantness, accompanied by that sneer.

This is why Lou Reed’s career has been both extraordinary and uneven. This is why a lot of those RCA albums from the ’70s are not merely produced distastefully—the quality is also actually shoddy: because that is what the career of an asshole looks like. Sometimes incredibly good work will get done because talented admirers will show up willing to do anything, and so you get an album like New York (made in the ’80s for Sire, but same thing), which was good work all around. But too often one is confronted by something like The Blue Mask, a beautiful contemplation of sobriety and love and commitment that has mediocre production values. Lou Reed’s post-Velvet career makes it obvious that it really was a band, because it’s only in those live recordings at the Academy in the early ’70s, like on Rock n Roll Animal, when Mick Ronson is on guitar, that solo Lou comes close to sounding as interesting as VU Lou. For all his talent, Lou Reed’s recorded output would be a whole lot better if a good collaborator—or two or three—were not so hard for him to find.

Lou Reed, of course, ought to be able to behave like a human being. But he’s not in the service industry—he’s not the waiter telling you about the branzino special, he’s not your florist or your cobbler or your chauffeur. It really doesn’t much matter if he’s polite or rude. It ought to matter to those in his intimate circle, and in the media saturated world, we ought to expect a good persona, but why do we need a good person? Because that’s what we need. The Kardashians are a barely-human shrine to the testament that all that matters is Lou Reed’s personality, because ability to create great works of art is no longer as valuable as a family full of K-named girls.

And that’s what I want to say on behalf of Lou Reed—but you can throw Dylan, Springsteen, Joni Mitchell, and a few others in there too: He came of age, went through a midlife crisis, and is now heading toward his shuffleboard Shangri-la days, in a time when a musician—and really, I should say, a person—truly could have a career. I mean, a substantial, lengthy career, one that allowed a relationship with an audience to develop with the same rhythms of a friendship, one that allowed for lousy work en route to genius, one that actually did allow the personality of the artist to become invested with meaning and significance that could be either delightful or deranged, one that made the music industry seem like a worthy enterprise and not just a bunch of schmucks who got lucky. And career in this context is a good word, it’s not a limiting notion like choosing to become a lawyer because what else is there; it’s a choice that is a real choice.

You might note that Lou Reed, and all the other people I pointed to almost parenthetically, have not hyphenated their lives. They aren’t designing a line of durable sportswear made of organic fibers for Kmart or running a small production company in a studio bungalow. They do the thing they do well, because it’s satisfying, and it’s a full life. And I’d say that people my age are the last group of Americans to know a life of creativity that can sustain a person financially, but also intellectually and emotionally. After us, it’s as if the world lost its ability to focus and stick to the plot. We will never know the life story of Vampire Weekend, because the curvaceous course of a life stretched out before us like a slinky unwinding is not a narrative that anyone knows how to sustain anymore.

What I think I’m saying is that what’s held my interest in Lou Reed through many anecdotes about his miserable personality and many albums that had maybe one good song on them, if that—“Coney Island Baby,” “The Bells,” I could go on and on—is the reality show that is Lou Reed was being expressed through all those albums, high and low, good and bad. He didn’t always get it right, but he tried to keep us informed, he tried to let us know what was up and what was what. He rightly titled an album Growing Up In Public, because that is what he got to do. Lou Reed gave us the first Velvet Underground album in 1965, when he was 23, which means we’ve had 46 years of living a tattered scattered life, one that was underneath the bottle, that involved waves of fear, that eventually brought him to the last shot, and that has gotten him to the point where he is living with and loving a woman who is his equal, who is a substantial person—an outcome about as unlikely as his recovery from heroin addiction (I’ve been told that about one in 35 manage it).

We got to hear this story. We got to hear a life happen in all its imperfection and misery and elation and contentedness, and realize again that the great thing about life is not that the future is predictable—it’s that you have absolutely no idea what will happen. Happy people consider that good news. And if you want to see that human story unfold, if you want to understand that only the unexpected life is worth a damn, spend some time with 46 years of Lou Reed’s work, music that leaped and then looked. Safety is for the godless and the faithless.

Elizabeth Wurtzel, the author of Prozac Nation, Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women, The Secret of Life, and More, Now, Again, is Tablet Magazine’s pop music critic.