This Is Not an Article About Jews in China

The world is infinitely broader and more interesting when it isn’t viewed through the lens of one’s identity

My dear grandma traveled all the way from Portsmouth, Virginia, to Middletown, Connecticut, to attend my Wesleyan graduation. After the ceremony, she treated the whole family and a few of my friends to a late lunch at old MacAndrew’s. The entrees being ordered, and with a little air creeping into the table talk, Grandma asked me what my honors thesis had been about.

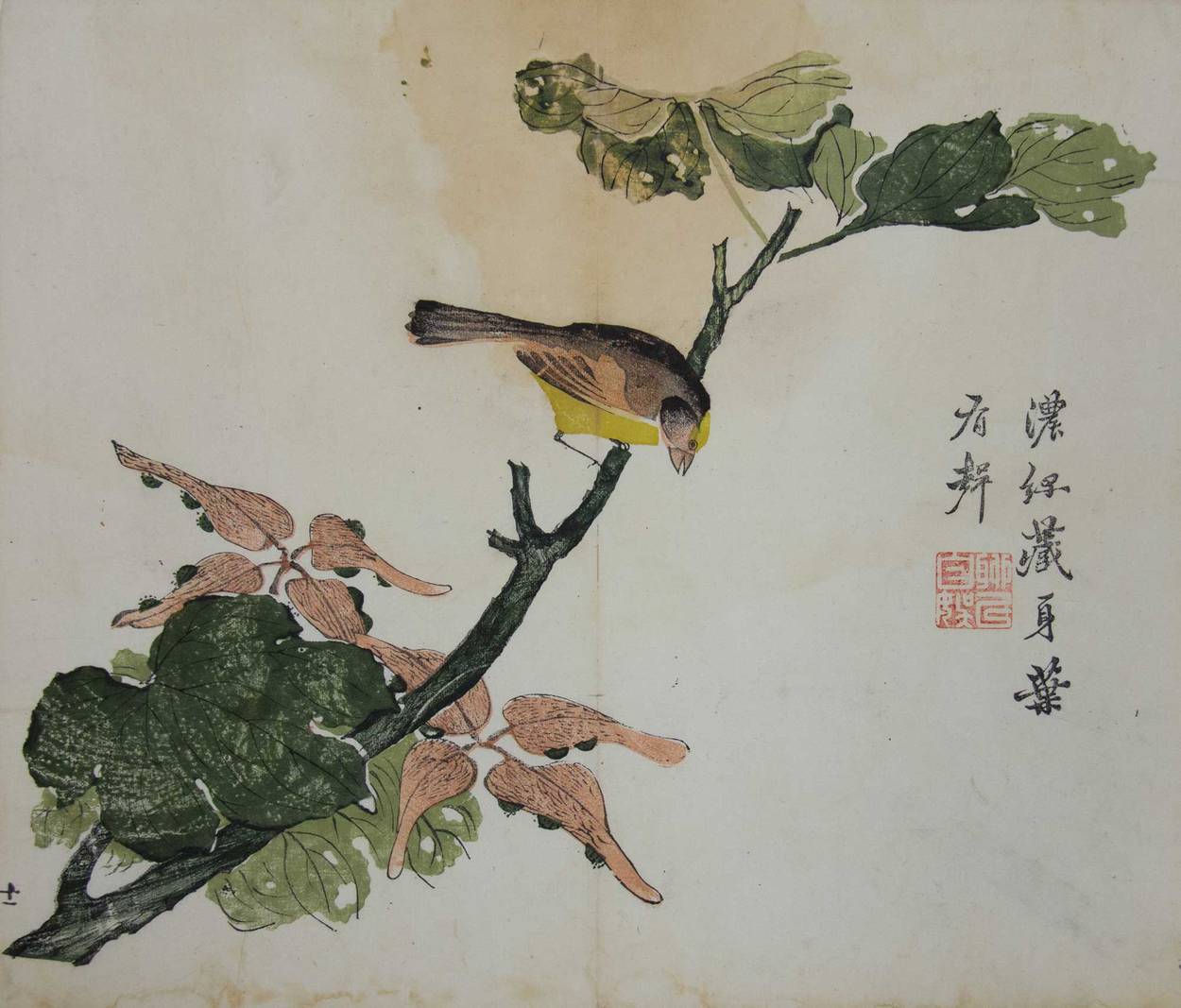

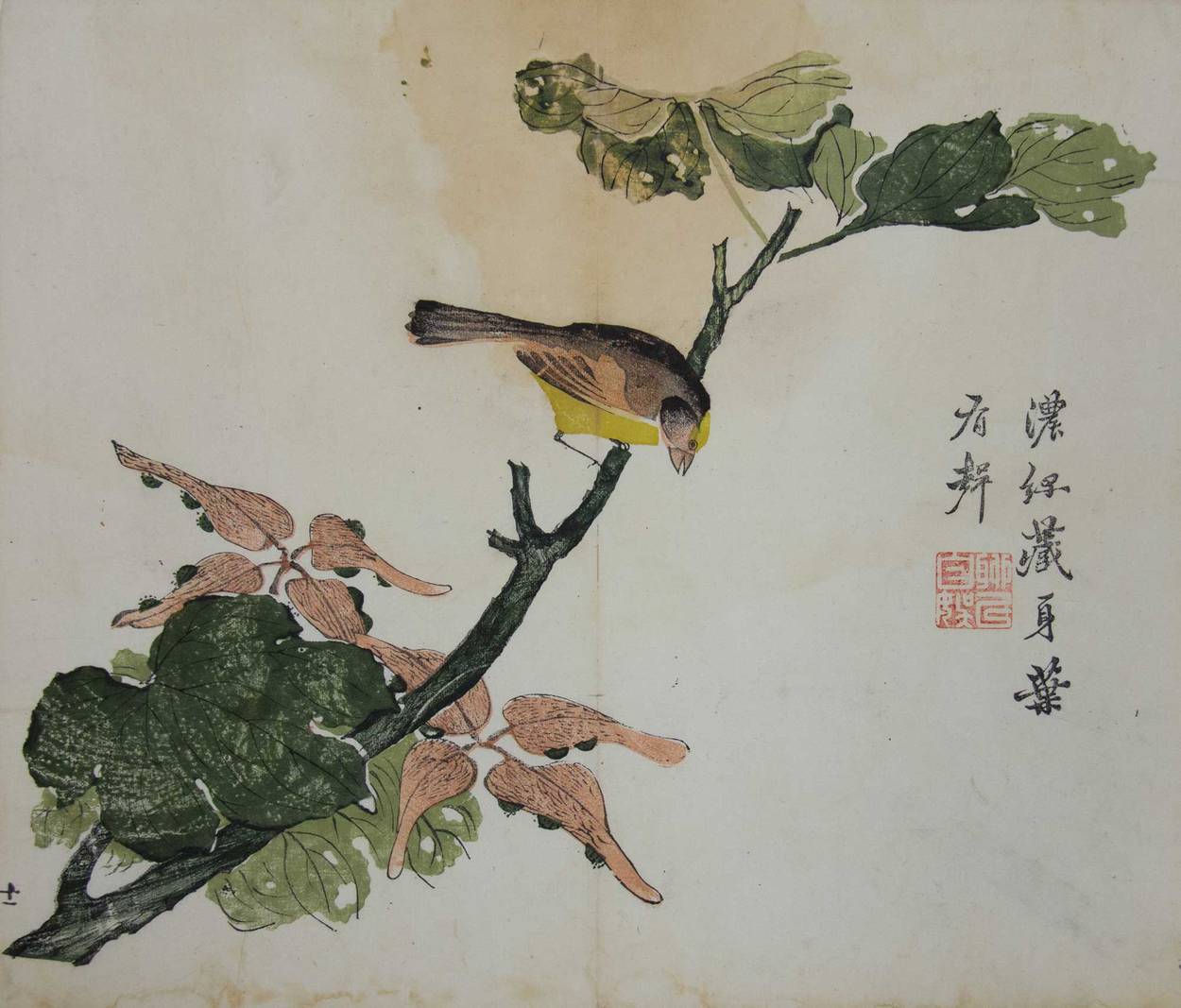

“Ming dynasty political history,” I replied (as Grandma nodded politely), “especially this group of fundamentalist Confucian scholar-officials from the last part of the dynasty called the Donglin faction. They were very critical of the emperor, and they attacked his policies as immoral. I think it’s interesting that they were using an ancient philosophy to do something … well, to do something kind of modern, like checking monarchial power. A lot of historians are looking at the 16th and 17th centuries in China to try to find signs of incipient modernity—like incipient democracy and incipient capitalism—but of course other Sinologists say that it’s wrong to expect China to have followed the same path of development that Western Europe did. I think it’s a fair inquiry, though, as long as it’s thought provoking.”

Grandma was having a sip of water. She nodded one more time as she put down her glass, and then she said, “I hear there were Jews in ancient China.”

What happened in my soul when she said that—and what has continued to happen with appalling frequency under similar circumstances ever since—forms the subject of this essay.

First, the basic facts: Yes, there were Jews in ancient China. I seem to remember that the Jews of the old Song dynasty capital of Kaifeng, and their descendants, were featured in several dentist office magazines in the late ’80s, when I suppose they came to my grandma’s attention. However, Grandma surely knew more about the Kaifeng Jews than I did, just from having read the articles in the dentist’s magazines (which I had not).

I loved my grandma very much and forgave her instantly for changing the subject on me, but the fact remains that change the subject she did. I also knew well that my grandma could find the Jewish aspect of anything. On the shelf in the den of her Portsmouth apartment she displayed a biography of Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, to express pride in our tribe’s contribution to the attempted murder of our country. Reflecting, furthermore, on her choice of like-minded friends, I recall how one of them lamented, at an exhibition of Civil War photo portraits at Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum, “It’s a shame awl the Jewish soldiers is Yankees”—the most singular utterance I’ve ever heard in a Southern accent.

Indeed, the abrupt diversion from Sinology to Judaica is something that I have continued to experience ad nauseam since I graduated from college, and then graduate school, and then on to teaching Chinese history. Every time this diversion occurs, it fills me with what William S. Burroughs called “a vertiginous, retching horror”—the horror of feeling 99.8% of the whole wide world fall away, leaving me with only the remaining 0.2% (i.e., the Jewish-identifying proportion of the world’s population). It’s very disconcerting to be focused on big things like China, Confucianism, politics, and history, and then to have my attention redirected to a relatively circumscribed and entirely different thing, like Judaism. In response, I feel more sadness than anything else. Wouldn’t you feel sad, if you had journeyed some distance to enjoy a panoramic vista, only to have someone proffer a tiny cardboard telescope for taking it all in?

It’s bad enough that, as the song goes, “Every girl I that go out with becomes my mother in the end”—meaning in this case that “Every thing that intrigues me becomes Judaism in five minutes flat”—but behind the tiresome presumption that I should be interested in all things Jewish lurks the more sinister notion that I shouldn’t be interested in anything else. In most cases, the admonition comes in the form of a rhetorical question: when goofing around with guitars as a teenager (“What’s a bunch of Jewish kids from suburban Baltimore think they’re doing playing Led Zeppelin?”), when feeling the Yuletide spirit (“What’s with the Hanukah bush, Bubbie?”), or even when having a little lunch (“A ham and cheese sandwich? Dude! Do I have to remind you that you’re Jewish?”).

I imagine at least some of you are saying, “So what? Can’t Jews in America ask you a simple question about Jews in China, or chide you about a Hanukkah bush, without you getting all bent out of shape? You’re still free! No one’s stopping you from studying China, or even from celebrating Christmas.” Yes, that’s all true. Maybe I am just pouncing unfairly on my own friends because they choose a familiar topic while making conversation. Maybe I’m a touchy freak.

Clearly, embedded within my sadness at the loss of the whole for the sake of a part, lies a bit of anger too. From whence comes the assumption that I should be interested in the Jews of China? Does my ancestry oblige me to be interested? Does it matter that I’ve spent my adult lifetime pursuing an interest in something else? Why did my friend recently send me an email containing nothing but the link www.chinesejews.com, under the heading “thought this would interest you”?

Why do these questions bother me so much? Well, it’s very vexing to be interrupted and put in my place, especially when I’m enjoying myself; and since most people seem to dislike being told what to do (or what not to do), I’m always surprised at how much they relish dishing it out. Injunctions to know one’s place, after all, are the kinds of things that drip from the mouths of British villains in the movies, like Lucius Malfoy sneering “You forget yourself, Potter,” so it’s odd to me that so many people whom I can safely suppose to be Harry Potter fans should play the Malfoy.

Of course, the Malfoys—the folks telling me to behave myself—are Jews. This little fact speaks volumes, but those volumes, in turn, are reducible to a single word, tribalism, which is something that has repulsed me since childhood. During the occasional bar mitzvahs I attended, the sermons—which I expected to contain instructions for better living—contained only desperate insistences as to the Jewishness of the congregation. (“Your Jewish identity is like the ancient Torah: not written on paper but carved in stone!”) I’ve always deemed it much more important to be a better person than a truer Jew, and so the world became my temple.

It’s not that I forget myself; it’s just that I choose to remember myself differently. The only identity that means anything to me is my American one. Americans are supposed to possess the right to the pursuit of happiness, which means that we are free to define happiness for ourselves, and then to pursue it, without having someone else define happiness for us and thus to sanction certain pursuits over others. At the risk of seeming to overreact, I’ve come to suspect—especially if I can’t even eat a fucking ham and cheese sandwich without fear of censure—that our denial of the right of self-definition (“Your Jewish identity is carved in stone!”) amounts to a renunciation of the right to the pursuit of happiness, for the former is essential to the latter.

I have a nightmare, a recurring one, or maybe it’s a memory of something that actually happened: I’m riding on a bus (in dream or in reality) in New York, and with me on the bus is a Black man reading The Autobiography of Malcom X, a guy with a yarmulke reading The Diary of Anne Frank, and an Asian lady reading The Joy Luck Club. That’s my nightmare. It’s a vision of a world without curiosity, without freedom, really, except the freedom to conform to type. Imagine yourself in my nightmare/memory as a Jewish-looking student trying to read de Toqueville, Tolstoy, or Tanizaki, amid a flock of yentas enjoining you to read something more appropriate, and you might be able to appreciate the hellish quality of my vision.

I see it everywhere around me on the campus where I teach, every day. I worry that as the cult of cultural conformity spreads, the ensuing loss of freedom may come with more than theoretical consequences. When I was adjuncting at Queens College in 1998, the head of the Jewish studies program there was let go because he wasn’t Jewish. The explanation for sacking him was that Queens’ Jewish studies students needed a “role model” (never mind that the incumbent was a role model, as a scholar and, God forbid, as a curious person). That rationale carried the day, resulting in a Jewish Jewish studies program head. In my own field, the scholar of the Nanjing massacre, Iris Chang, researched and wrote about the atrocity out of devotion to her grandparents, who were in it. (I am reluctant to write anything even incidentally negative about Iris Chang, not least because her book on Nanjing is so important; but the truth is that I felt threatened by her work as soon as I learned of it, for fear that the “family history” approach would become normative.)

The examples of Iris Chang and other academics with personal connections to their subjects, combined with perennial requests that I comment about Chinese Jews, have alerted me to the possibility that my area of expertise, and with it my choice of profession, might soon cease to make any sense to people. Are younger students going to keep taking Chinese history classes from non-Chinese professors like me? Are my credentials—curiosity and a desire to make sense out of unfamiliar things—destined to lose credibility in an ever-denser atmosphere of cultural correctness? With a lifetime of good reason, I live in daily dread of the fatal question: “What’s a Jewish guy from suburban Baltimore think he’s doing, teaching Chinese history?”

As freedom gives way to authenticity, I’ll continue to live eclectically and to follow my inclinations wherever they lead me, as they lead me now to “Free and Easy Wandering,” the beautifully entitled first chapter of the Daoist classic Zhuangzi:

In the bald and barren north, there is a dark sea, the Lake of Heaven. In it is a fish which is several thousand li across and no one knows how long. His name is Kun. There is also a bird there, named Peng, with a back like Mount Tai and wings like clouds filling the sky. He beats the whirlwind, leaps into the air, and rises up ninety thousand li, cutting through the clouds and mist, shouldering the blue sky, and then he turns his eyes south and prepares to journey to the southern darkness.

The little quail laughs at him, saying, ‘Where does he think he’s going? I give a great leap and fly up, but I never get more than ten or twelve yards before I come down fluttering among the weeds and brambles. And that’s the best kind of flying anyway! Where does he think he’s going?’

Harry Miller teaches Asian history at the University of South Alabama. He is the author of Southern Rain, a novel set in 17th-century China.