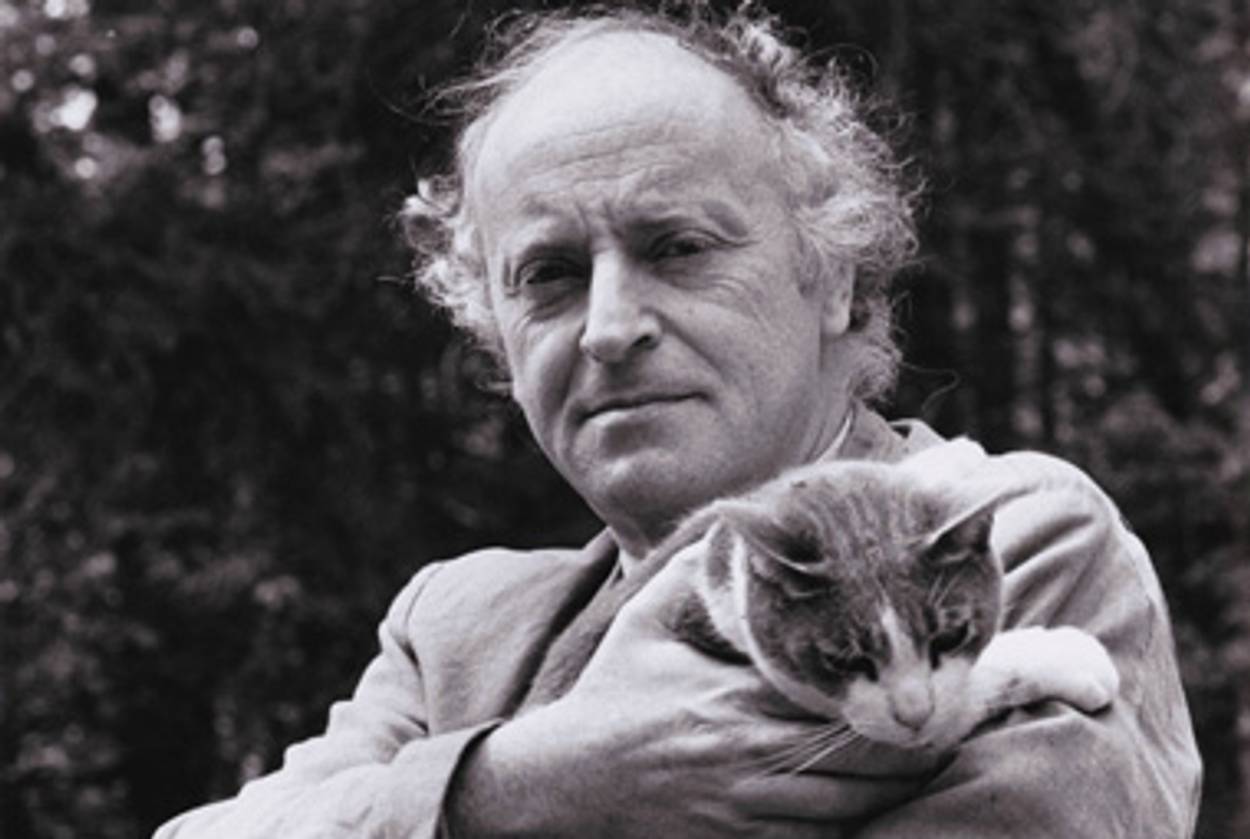

Nowhere Man

The poet Joseph Brodsky, kicked out of the USSR and never fully at ease writing in English, was a man of many residences and few homes, as a new biography shows

With most writers, the passage of time helps to consolidate their achievement and fix their reputation. Fifteen years after a poet’s death would seem like ample time for this posthumous process to be completed—especially in the case of a poet as famous as Joseph Brodsky, who became internationally known in his twenties and won the Nobel Prize in 1987. Certainly there is no mystery about the standing of poets like Seamus Heaney or Derek Walcott, Brodsky’s friends, contemporaries, and fellow-laureates. Whether you enjoy reading Heaney or not, the shape of his achievement is clear; his name stands for a certain kind of writing and thinking.

Brodsky, however, continues to look a little blurry to American readers. His work does not have the currency or influence, among younger poets, that his reputation would suggest. Some critics, especially in England, are prepared to dismiss him entirely, to call his work overrated and his reputation unearned. But most simply ignore him, as though he did not belong to the same conversation that includes Heaney or John Ashbery or Adrienne Rich.

In one crucial sense, of course, he does not. All those poets write in English; but Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky, born in Leningrad in 1940, was a Russian poet. This means that it is Russian readers, familiar with Brodksy’s language and literary tradition, who must decide his claims to greatness. And as Lev Loseff shows in Joseph Brodsky: A Literary Biography, his clarifying new book, the best Russian judges have been unanimous about Brodsky from the beginning.

When he was 21 years old, for instance, he was introduced to Anna Akhmatova, the tragic heroine of 20th-century Russian poetry. Loseff, a poet and friend of Brodsky’s, explains that such “pilgrimages” to Akhmatova were common for young writers, who would arrive “bearing flowers and notebooks full of poetry.” Unsurprisingly, the encounter made a deep impression on Brodsky: “I suddenly realized—you know, somehow the veil suddenly lifts—just who or rather just what I was dealing with.” What is more surprising is that Akhmatova, then 72 years old, immediately accepted Brodsky as an equal: “Iosif, you and I know every rhyme in the Russian language,” she told him. In 1965, after reading a poem of Brodsky’s, she wrote in her diary: “Either I know nothing at all or this is genius.”

There is nothing new about English readers being baffled by poetry that Russians adore. On the contrary, it’s a critical truism that Russian poetry doesn’t translate well. Pushkin occupies the same place in Russian literature as Shakespeare does in English, but it has always been hard for us to really understand why. Twentieth-century masters like Osip Mandelstam and Marina Tsvetaeva are probably as well known in America for their life stories as for their writings. If Brodsky belongs in their company, then it makes sense for him to remain a little obscure to Americans, just as they do.

What makes Brodsky’s case so unusual is that this Russian poet spent almost half his life in America. Between 1972, when he was expelled from the USSR, and his death in 1996, Brodsky traveled extensively—“probably no Russian writer ever traveled more,” Loseff writes. But his home bases remained New York, where he lived in a two-room apartment on Morton Street, and South Hadley, Mass., where he taught at Mount Holyoke College. He even managed to become a vital figure in the American literary world, eventually being named U.S. Poet Laureate. This was possible, in large part, because Brodsky translated his own later work into English—first with the help of translators and other poets, then on his own. (Eventually he even wrote some modest original poems in English.) These versions were the ones included in his American collections, published by Farrar Straus Giroux, and now available in Brodsky’s Complete Poems in English.

Yet few English readers have been really satisfied with Brodsky’s own translations. His desire to make them is understandable—by turning himself into an American poet, after a fashion, he was saved from the obscurity and resentment that is the usual lot of the literary émigré. But he never became a master of English, in the way that, say, Vladimir Nabokov did. (As Loseff points out, Brodsky came to English much later than Nabokov and was largely self-taught, while the well-born novelist had English tutors from childhood.) Indeed, Brodsky in English remains, all too often, wrenched, unidiomatic, and unmusical. The genius of the Russian poet can be intuited—you can sense it in Brodsky’s intellectual range, bold metaphors, and rhetorical flow—but not really experienced. Loseff quotes the American poet Robert Hass to the effect that reading Brodsky in English is “like wandering through the ruins of a noble building.”

Loseff’s book is, as its subtitle insists, a strictly literary biography. The outlines of Brodsky’s life are sketched, but private experiences are related only when they directly inspired his poetry. Thus Loseff tells, in brief and general terms, the story of Brodsky’s long, tumultuous love affair with a woman named Marina Basmanova, which drove him to a suicide attempt, produced a son, and inspired some major poems. On the other hand, Brodsky’s marriage, late in life, is dispatched in a single sentence, and there is little about other friendships or relationships.

Where Loseff excels is in sketching the Russian literary and cultural context for Brodsky’s work—the poets he knew and admired, the “schools” that dominated Leningrad poetry in his youth. This kind of analysis is a reminder of how little Brodsky can be understood through an American prism. Likewise, the excerpts from his early Russian poems, translated (along with the whole book) by Jane Ann Miller, show how much we would benefit from a comprehensive new translation of Brodsky’s poetry. Miller’s excellent work is only seemingly slighted by the odd way that each of her verse translations is followed by the word “non-poetic”: This is to show that the translation is not by Brodsky, but in fact, her lucid and convincing versions are often more effectively poetic than the poet’s own.

Joseph Brodsky: A Literary Biography also helps to shed light on the complex question of Brodsky’s Jewishness. In one sense, Brodsky is unequivocal on this subject: “I’m a Jew. One hundred percent. You can’t be more Jewish than I am,” he told an interviewer. Yet he was typical of his Soviet Jewish generation in having absolutely no knowledge of Judaism—apparently he did not even read the Bible until he was in his twenties—and his understanding of Jewishness seems to have been passive and minimal. “When anybody asked what my ethnic background was, I of course answered Jewish,” he explained, “but that didn’t happen often. There was really no need to ask. I can’t say a Russian r.” Brodsky saw Jewishness in terms of such details of speech and appearance, like his prominent nose and pale skin. It could also be a cause of (fairly minor) discrimination: He recalled being teased by classmates and having his application to the Naval Academy rejected because of anti-Semitism.

But his essential identity, as he created it in his poems and essays, was universalist and cosmopolitan. Its key ingredients were the Russian language, European art and literature, and classical history: “Roman Elegies,” “To Urania,” “Venetian Stanzas,” and “Twenty Sonnets to Mary Queen of Scots” are typical Brodsky titles. He seems to belong to the noble tradition of Jewish writers who, emancipated or severed from Jewishness, became universal humanists. One thinks of Marx, or Freud, or especially, in this case, Osip Mandelstam, whom Brodsky described in a superb essay as “a little Jewish boy with a heart full of Russian iambic pentameters.” The phrase is obviously autobiographical as well, and when Brodsky calls Mandelstam “the child of civilization,” he could be describing himself.

The story of the orphaned Jew who is reborn as the child of civilization is one of the great and ambiguous legends of modernity; and all such stories include a scene where the child is forcibly reminded that civilization doesn’t always trump history. That moment came for Brodsky in 1972, when he was abruptly summoned to the Leningrad bureau of OVIR, the office of visa and registration. The acronym was much in the American news at the time thanks to the Soviet Jewry movement. As Gal Beckerman writes in his recent book When They Come For Us We’ll Be Gone, it was OVIR that obstructed Soviet Jews from going to Israel—or, at certain politically opportune moments, made emigration possible. This was one of those moments—in 1972, 32,000 Jews were allowed to leave as a token gesture in advance of President Nixon’s visit to Moscow.

But Brodsky was quite surprised to be one of them. He was by no means a refusenik, and the reason why he was persona non grata with the Soviet regime had to do not with his identity as a Jew, but with his identity as a poet. In 1964, Brodsky had been denounced by a Communist party loyalist for the vague crime of “parasitism,” or refusal to work. In fact, Loseff writes, he held a number of jobs, many of them quite arduous—he had worked on a geological expedition to the Arctic and as an assistant to a boiler inspector. But he had no real career, preferring short-term work that kept his time free for writing, and he shunned the established literary clubs and unions.

In short, he was acting just as a poet should—educating himself in his art, preserving his freedom, steering clear of cant and obligation. In the USSR, however, this was an intolerable display of independence, and Brodsky was subjected to a trial that truly merits the adjective Kafkaesque. As Loseff shows, the witnesses against him were a cross-section of ordinary citizens—a clerk, a soldier, a retiree—who all “began their testimony by stating that they did not know Brodsky personally.” Indeed, they hadn’t even read his poems, few of which had been published at the time. Their testimony amounted to stating that, based on what they had read about Brodsky in slanderous, error-filled newspaper articles, they believed him to be “anti-social.”

The judge, a caricature of a party hack, asked Brodsky who had given him the right to call himself a poet: “Did you try to attend a school where they train [poets]?” His reply—“I don’t think it comes from education … I think it’s from God”—is deservedly legendary. Indeed, the trial created such a loathsome spectacle—a stupid bureaucracy persecuting an idealistic young poet—that it became an international embarrassment for the Soviets. Brodsky was sent to do hard labor in exile, but after pressure from abroad, including a statement by the usually pro-Soviet Jean-Paul Sartre, his sentence was commuted after a year.

The official malice toward Brodsky remained, however, and he was not allowed to publish his poetry in the USSR, even as unauthorized editions appeared abroad. In 1972, then, the authorities decided to take advantage of the Soviet Jewry agitation to get rid of Brodsky once and for all—and it was his Jewishness that gave them the means. Summoned to OVIR, he was told that he must write out a statement accepting an invitation to Israel, or else he’d be “in big trouble.” He had no interest in going to Israel, or even in leaving the country; but within four weeks Brodsky was on a plane to Vienna, the transfer point for Jewish émigrés. He never returned to Russia, not even after the fall of Communism, and he never saw his parents again. Nor, of course, did he go to Israel; and while he became an American citizen, his body is buried in Venice. Loseff quotes his friend Susan Sontag’s telling explanation: “Venice was the ideal place to bury Brodsky, since it was essentially nowhere.” Does being a child of civilization mean belonging everywhere and nowhere? As Brodsky himself put it, in his poem “Venetian Stanzas I”: “At night here we hold soliloquies/ to an audience of echoes, whose breath won’t warm up, alas.”

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.