The Odd Knight of the Cinnamon Shops

A new book explores the life and tragic death of Bruno Schulz, the great Polish Jewish magical realist writer and artist murdered by the Nazis

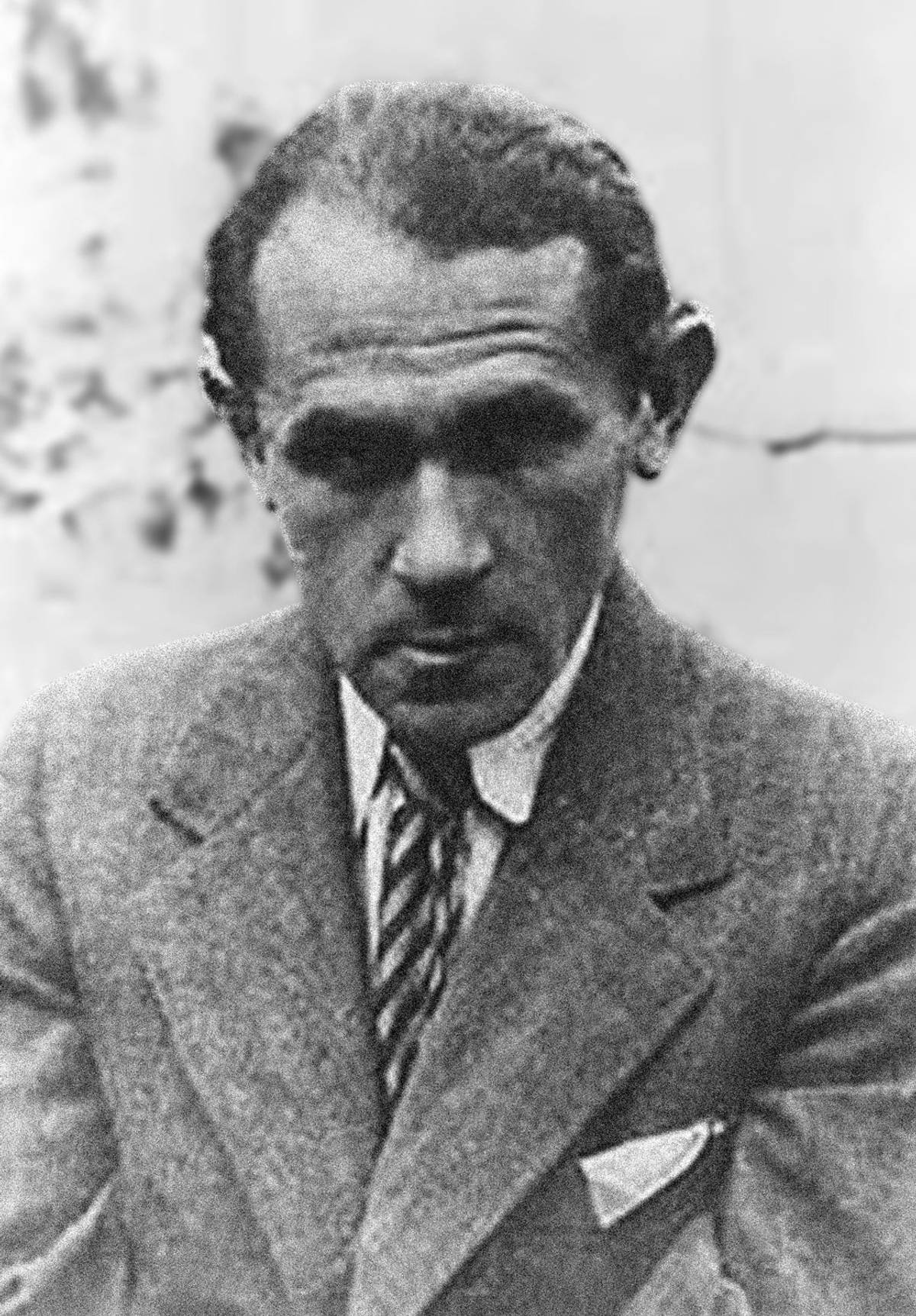

On Nov. 19, 1942, at the age of 50, Bruno Schulz, writer, artist, and idiosyncratic dreamer, was murdered in the ghetto of Drohobycz, Galicia. Earlier that month, Felix Landau, the SS officer who forced Schulz to produce works of art for him, had shot a Jewish barber enslaved by Karl Günther, another SS man. “You killed my Jew, I killed yours,” Günther said to Landau after murdering Schulz. At least, that’s the version of Schulz’s death that David Grossman recounts in his virtuosic novel See Under: Love.

In his new book, Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History (W.W. Norton, April 11), Benjamin Balint explains that Schulz’s death is highly disputed. He was certainly murdered on Nov. 19, but there are at least five different versions of what happened. According to various witnesses, he was killed by Landau himself, by Nazi gendarmes, by a Gestapo officer named Fritz Dengg, or by another Gestapo man who saw him feeding pigeons. That day was called Black Thursday in Drohobycz. A Jewish pharmacist had gotten hold of a pistol and shot a Gestapo guard’s finger, and in retaliation, the Germans were shooting hundreds of Jews in the streets.

Balint has done extensive research into Schulz’s life as well as his death. Like Balint’s previous book, Kafka’s Last Trial, about the legal battle over the Kafka manuscripts finally consigned to Israel’s national archive, Bruno Schulz deals with an author who straddles several cultures and is claimed by both—in Kafka’s case, Jewish and German; in Schulz’s, Jewish and Polish. Schulz felt an affinity for Polish writers like Witold Gombrowicz and Witkacy (Ignacy Witkiewicz), and his greatest critical advocate was Jerzy Ficowski, another Polish gentile. The late Polish poet Adam Zagajewski, a much-missed friend and colleague, has written movingly about him.

Schulz himself said that he was “an Austrian, a Jew, a Pole—all in the space of an afternoon.” One of his stories plays whimsically with the image of Kaiser Franz Josef, the aging colossus who presided over the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During Schulz’s childhood, Drohobycz was about 40% Jewish, 30% Polish, and 30% Ukrainian, testimony to the mixture of cultures under Franz Josef’s reign.

Schulz wrote in Polish, which his family spoke at home. He knew little Yiddish and even less about the Jewish religion. In his story “The Book” he prefers a multicolored advertising catalog, a true source of phantasmagoria, to the Bible (“Bent over the Book, my face aflame like a rainbow, I burned in silence from ecstasy to ecstasy”). Yet Schulz was murdered because he was a Jew, like 3 million others—90% of Poland’s Jewish population—and his fate has a claim on all his readers.

After oil was found near Drohobycz in 1869, the region became “the Polish California,” as Joseph Roth called it, dotted with drilling towers. Schulz ignored the oil barons who built their mansions in Drohobycz. In his fiction the town is full of merchants whose stores lined the streets. In these “cinnamon shops”—so called because of their brown wood paneling—“you could find Bengal lights ... magic boxes, stamps of long-vanished countries, Chinese decals, indigo, colophony from Malabar, the eggs of exotic insects, parrots, toucans, live salamanders and basilisks, mandrake root, windup toys from Nuremberg, homunculi in flowerpots, microscopes and telescopes, and, above all, rare and unusual books ...” Here was a “self-sufficient microcosm, installed ... on the very brink of eternity.” Schulz swore to a friend that he could live nowhere else.

The Russian Army, which invaded Galicia in 1914, turned the Schulz family into refugees. Bruno’s father died the following year. Bruno spent the war years in Vienna, returning to Drohobycz in 1918. During the next few years over 100,000 Jews were killed in pogroms carried out by Poles and Ukrainians.

In 1924 Schulz began teaching art and woodworking at the high school in Drohobycz, a job he would hold for the next 17 years. The drudgery of teaching made him feel “brutalized and soiled inside,” he said. His students remembered Schulz, who was frail and shy, as a magical storyteller. Instead of teaching, he spun tales for the class. “He told stories, and we listened ... the wildest kids sat there enchanted,” one former student remembered. “He was never angry, never raised his voice,” another said.

Schulz, who was timid by nature, inhabited a private kingdom of dreams. In a letter to the psychologist Stefan Szuman (July 24, 1932), Schulz reflected on his “state of spellbound suspension within a personal solitude.” He recounted his “truest and profoundest dream,” which he had at age 7: “I am in a forest at night, in the dark; I cut off my penis with a knife, scoop out a little cavity in the earth, and bury it there.” Struck by “the horror of the sin I have committed,” Schulz felt burdened by eternal guilt for this fantasized self-mutilation. He clung all his life to the posture of helplessness, like one of the damned writhing inside a glass globe of marvels.

Schulz sought refuge in his fantasy world, the only place he could truly exist. His drawings show imperious, lithe femmes fatales dominating small shame-faced men resembling Schulz himself. The men slink around under the sway of the implacable doll-like women, worshipping their legs and feet. Schulz’s females are languid, alien-looking and oddly childlike; they ignore the men who idolize them.

Hints of Schulz’s masochism appear in his stories. His women are slender, imperious, and aloof, and they delight in teasing the men, especially Jakub, the father of the youthful narrator Jozsef, who stands in for Schulz. The father, a cloth merchant, becomes increasingly strange, obsessed by his recondite scholarly pursuits. Spindly and half-alive, wriggling under his desk lamp, in the end he turns into a cockroach, “merg[ing] completely with that uncanny black tribe.” He becomes a puny nightmare grotesque, a mere toy for his son’s imagination to play with.

In a 1935 essay Schulz compared his first book to Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, which weaves biblical narrative together with “the timeless myths of Babylon and Egypt.” Schulz said that his own work, far more modest than Mann’s gargantuan, labyrinthine novel, “follows the spiritual family tree down to those depths where it merges into mythology, to be lost in the mutterings of mythological delirium.”

Schulz’s fiction is in fact delirious. A hothouse full of peculiar orchids, his writings seem to have sprung from the tropics rather than wintry Poland, as Rivka Galchen remarks in her preface to Madeline Levine’s superior recent translation of Schulz’s stories. Schulz is obsessed with the luscious and fertile spring and the claustrophobic heat of summer. Like García Márquez, he offers the reader a Wunderkammer full of fantastic oddities. An early magical realist, Schulz is also a decadent in the manner of Lautréamont and De Quincey.

Schulz’s narrator often fixates on the languorous, self-possessed family maid: “Adela, warm from sleep, her hair tousled, was grinding coffee in a mill, pressing it to her white breast from which the beans took on a radiance and heat. The cat was licking itself clean in the sunlight.” Schulz’s work is a fever dream, transfixing the reader, just as young Jozsef is intoxicated by Adela’s lazy gestures.

Schulz’s childhood memories were a “secret entrusted to him,” he said, and he wrote his stories because he longed to grasp their meaning. Like Proust he treasured the glimpses that broke through from youthful existence into adulthood. His work, a lush web, bursts with one sensual revelation after another, like the advertising catalog he pores over with near-orgasmic intent.

Balint portrays the bright side of Schulz’s emotional life as well as the dark. In 1937 Witkacy brought a young woman to his apartment, a barmaid named Alicja Mondschein. He told her that when Schulz opened the door, she should immediately slap him. She did, and Schulz fell down awestruck at her feet. He became friends with Alicja, and the two romped through the streets of Zakopane, a resort town near Krakow. They played hopscotch, while pedestrians muttered about “those two weirdos.” Alicja was tall and in her 20s, with a bare midriff, a short orange skirt and long, tanned legs. The diminutive Schulz, then in his mid-40s, cavorted in a jacket and beret.

Philip Roth was largely responsible for Schulz’s revival among English-speaking readers. Roth arranged for the reissuing of Schulz’s two books of short fiction under the Writers from the Other Europe imprint in the 1970s. Cinnamon Shops, Schulz’s first book, appeared as The Street of Crocodiles, and was followed by The Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. Since then, not only Grossman, but Cynthia Ozick and Nicole Krauss have drawn on the haunting figure of Schulz. In The Messiah of Stockholm, Ozick imagines the rediscovery of Schulz’s famous lost manuscript, a novel called The Messiah. The Quay brothers made a short film based on Schulz’s story “The Street of Crocodiles.” Every two years now in Drohobych, Ukraine, there is a festival dedicated to Schulz, attended by legions of scholarly fans, who call themselves Schulzoids.

In 2001 an international rescue mission claimed Schulz’s art for the Jews. A team from Yad Vashem, with the approval of Drohobycz’s mayor, removed what was left of the murals that Schulz painted for the children’s room in Felix Landau’s house, and took them to Jerusalem, where they are now on display. The fallout was instant: Israel was accused of art theft, though Schulz’s work had not been designated a cultural monument by Ukraine. John Czaplicka, a historian of Ukrainian culture at Harvard, wrote, “Perhaps the Mossad should now start spiriting away artworks painted by Jews in German or Austrian museums or carving out the walls wherever a ‘Jewish’ painter left her/his mark. ... Does Israel have the ‘God-given’ right to all cultural goods produced by Jews?”

Czaplicka’s inflammatory words to the contrary, Schulz was killed for being a Jew, and so, Yad Vashem said in an official statement, his murals belonged in Israel. While Schulz did his paintings in the children’s room he was being fed only a slice of bread and a bowl of soup each day by his “protector” Landau. The murals feature fairytale motifs, and the faces of knights, squires and kings have noticeably Jewish features, a sly subversion of his Nazi masters. Moreover, the murals, according to Yad Vashem, “were in a state of severe deterioration, having been neglected for over 55 years,” and were now being restored. The Israeli Holocaust museum “dismisse[d] attempts by any country to claim monopoly on an internationally acclaimed artist.”

Seven years after Israel took Schulz’s artwork, the Jewish state signed an agreement with Ukraine. The murals would stay in Yad Vashem on loan from Ukraine for 20 years, after which the loan could be renewed. Israel was acknowledging that it did not own Schulz or his work—at least not officially.

Schulz made about 100 pages of notes on the scenes of cruelty he witnessed in the Drohobycz ghetto. They have all been lost. By the time Schulz was murdered, 20 to 30 Jews were dying of starvation each day in the ghetto. This was the end of the beloved town that Schulz adorned with his lavish mythic inventions—his equivalent of Joyce’s Dublin or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, Balint remarks.

Drohobycz has today become a Ukrainian city (and renamed Drohobych), largely oblivious to its multicultural past. After Yad Vashem spirited away Schulz’s murals, Ukraine’s government protested that Drohobycz, which Schulz loved so wholeheartedly, had the sole right to his legacy. Polish officials also condemned the Israeli action. Yet until the murals’ removal, Drohobycz, which never erected a monument to Schulz, cared little about him. This is perhaps not surprising, since Schulz hardly noticed the Ukrainian contribution to Drohobycz’s culture.

Schulz is a case study of what happens when a writer’s legend fuses with his work. It is tempting to see his whole career through the lens of his terrible death. But he was little interested in prophecies of destruction, and he never foresaw the Holocaust that killed him. He was a slightly built, modest knight of eros, whose custom-built world glimmered with timeless, fertile energies, a land of cinnamon shops, crocodiles, stamp albums, and goddesslike women.

Schulz’s destiny is terrifying and exemplary, and Balint retells his life in captivating fashion. But what really matters is that readers keep finding refuge in what Adam Zagajewski calls his “downy prose,” which is sensitive, opulent, and utterly allergic to the ordinary.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.