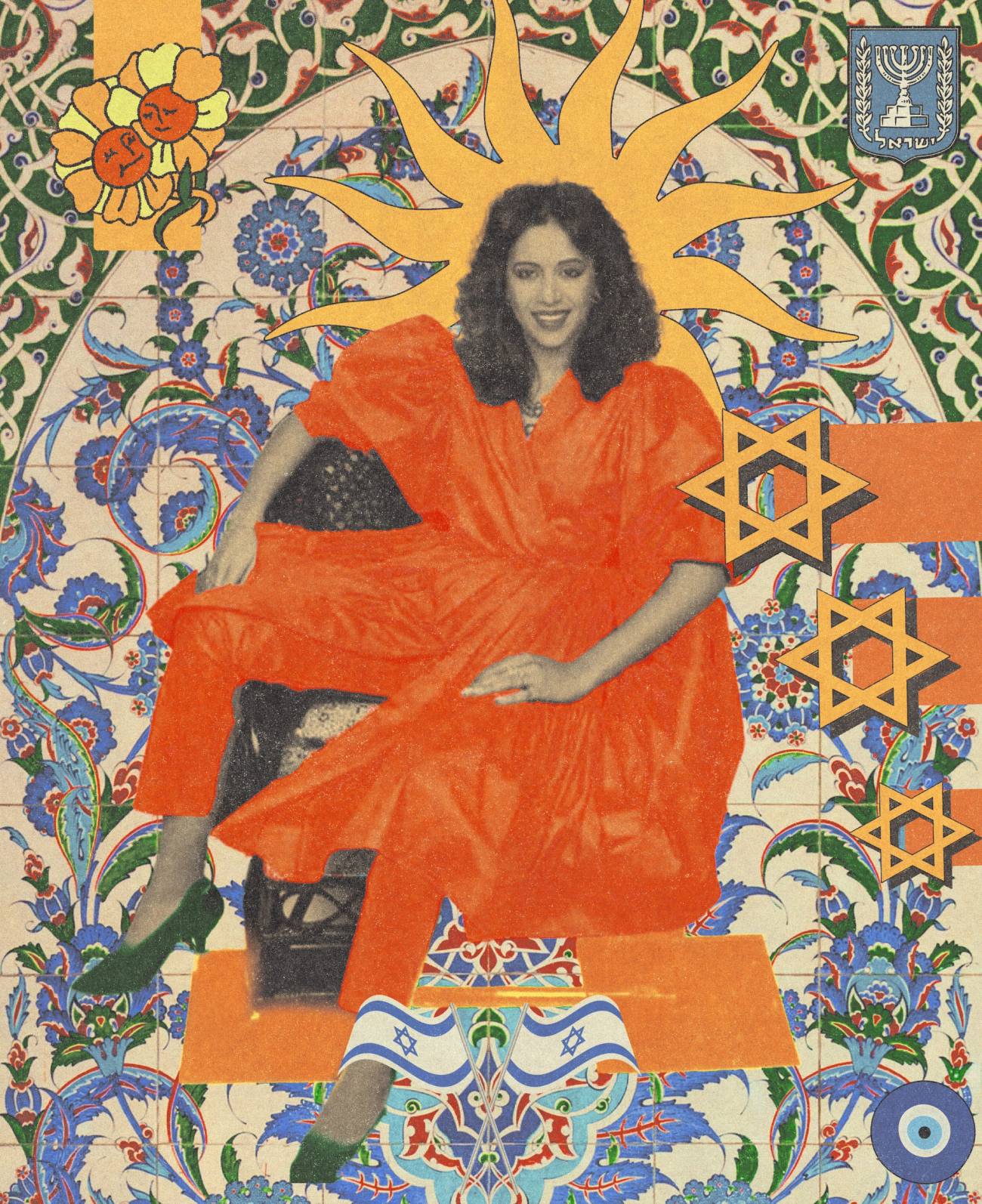

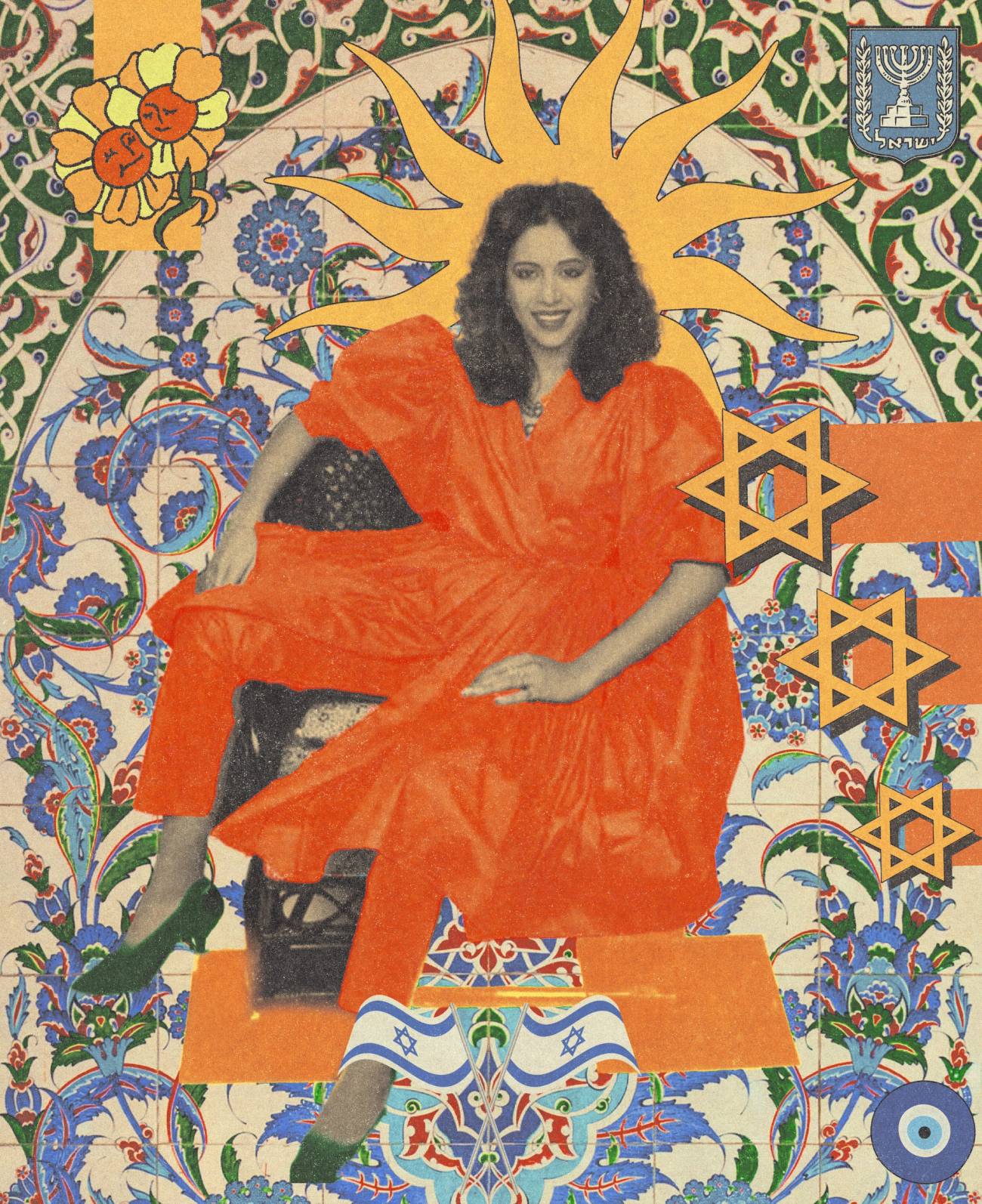

Ofra Haza, Tragic Israeli Pop Diva

The incandescent Yemeni Israeli singer sampled on Eric B. and Rakim’s ‘Paid in Full (Seven Minutes of Madness)’ died 23 years ago today

For Israelis, 2023 started with a great feeling of pride. On Jan. 1, Rolling Stone published its new list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time. There, at number 186, between Alicia Keys and Bonnie Rait, was Israel’s very own Ofra Haza. This surprising honor, coming 23 years after Haza’s death, is an excellent excuse to revisit the music of the “Madonna of the Middle East” and her magical, mysterious, and ultimately tragic story.

Ofra Haza remains, to this day, one of Israel’s biggest cultural icons, with nine streets named after her across the country and a postal stamp bearing her image. Born in 1957 to Yemeni Jewish immigrants, Haza grew up in a traditional family in Hatikva Quarter, a working-class neighborhood in south Tel Aviv. As a young girl, she began singing at local weddings, and at age 13, she was recommended to Bezalel Aloni, the manager of Hatikva Quarter’s Theater Troupe. Despite Haza’s tender age, Aloni recognized her potential and took her under his wing, and her career took off, first as an actress-singer on stage and in musical films and later as a bona fide pop star.

After releasing three albums with Aloni’s Theater Troupe, Haza released her first solo album in 1980. In Israel, she came to be associated with light pop and the genre known as Zemer Ivri—a clean-cut style of easy-listening music with folky roots and Zionist sentiments. By the early 1980s, she was a national celebrity, winning “Female Singer of the Year” four years in a row. In 1983, she took her first step toward international stardom by participating in the Eurovision Song Contest. Her entry, “Hi”—which was actually “Chai” in Hebrew, meaning “alive”—came in second place.

A year later, at the height of her success, she released a collection of songs very different than what her fans were used to. Yemenite Songs, released internationally as Fifty Gates of Wisdom, was an album of Yemenite folk songs—some ancient and some written in the vein of those traditional songs—that Haza dedicated to her parents. Israeli radio was baffled. The songs didn’t fit into the usual Zemer Ivri or pop of mainstream radio, and so it was only played on Mizrahi music programs, though it wasn’t Mizrahi music either. But if Israel didn’t know what to do with the album, it kickstarted Haza’s international career. In Europe, a new marketing category called “World Music” was starting to gain popularity. The West was craving “authentic” music from faraway lands, and this is exactly what Haza brought them.

A dance remix of “Galbi,” a song written and composed by Aharon Amram and produced by Izhar Ashdot, started to make waves in the U.K. This prompted another remix, this time of “Im Nin’alu,” Haza’s interpretation of Rabbi Shalom Shabazi’s 17th-century poem. Ashdot’s official remix of “Im Nin’alu” became a huge dance-floor hit in Europe in 1988 and made a splash in the U.S., too, reaching No. 15 on Billboard’s Hot Dance Club Play Chart. The song’s vocal intro was also sampled by English electronic duo Coldcut in their remix of New York hip-hop duo Eric B. & Rakim’s “Paid In Full.” Haza became an international ethnic-dance sensation, winning “Female Singer of the Year” in Germany twice in a row.

The remixes of “Im Nin’Alu” and “Galbi” appeared on her first international album, Shaday, released in 1988. This was the decade in which European pop culture was fascinated and titillated by anything exotic. German synth-pop band Alphaville conquered MTV with kimono girls in the video for “Big in Japan”; Duran Duran shot videos with exotic body-painted models in the Sri Lankan jungle; David Bowie protested racism by parodying Asian female stereotypes in the video for “China Girl.” Europeans were fantasizing about beautiful dark maidens who didn’t speak a word of English, and Haza fit the mold perfectly. She toured the world, wowing audiences from Tokyo to New York with her blend of Yemenite music and modern pop.

The first time we Israelis saw Haza through the eyes of foreigners, it was somewhat surprising, like the uncanny makeover scene in a teen movie. Haza’s image in Israel was always squeaky clean—smiling, innocent, wholesome, full of love and optimism. Seen from the vantage of the Western male gaze, however, she was suddenly tantalizing and seductive. The innocent girl we knew was suddenly replaced by Scheherazade—exotic, erotic and untouchable. Haza, with her dark beauty and endless charm, played the part.

The early 1990s were the peak of Haza’s international career. She collaborated with superstars ranging from Paul Anka to Paula Abdul, Sarah Brightman to Iggy Pop and The Sisters of Mercy. In 1993, she became the first Israeli to be nominated for a Grammy award, for her album Kirya, co-produced by Don Was. Her songs were featured in movies such as Dick Tracy and Wild Orchid. She did talk shows around the world—including Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show—and she performed at the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo. One of Haza’s last projects was voicing the character of Yocheved, mother of Moses (which was also illustrated to resemble her), in the DreamWorks animated musical drama The Prince of Egypt, based on the Book of Exodus. Haza sang Yocheved’s dramatic song, “Deliver Us,” composed by Hanz Zimmer. She voiced Yocheved’s dialogue in the original English version and in the Hebrew version, but being the professional that she was, she performed the song itself in 18 different languages for the film’s dubbing.

But at some point along the way, her career began to falter, for unclear reasons. It has been said that bad business decisions were made, either by her or by Aloni. Whatever the case, it was all cut short by her untimely death in 2000, at the age of 42. Which brings us to the great mystery of her personal life.

To say that Ofra Haza kept her private life private would be a huge understatement. More accurate to say: She lived her life in hiding. For years, the Israeli press speculated about when would she get married. She often claimed to have a boyfriend, but her boyfriends were nowhere to be seen. The first man she introduced to the media was Doron Ashkenazi, a divorced father of two, whom she married in 1997. Afterward, she severed her ties with Bezalel Aloni and let her husband manage her career. Less than three years later, she was dead from AIDS. Ashkenazi died the next year from a cocaine overdose. The media revealed that he was HIV-positive too.

The cliché in Israel is that Haza didn’t die of AIDS, she died of shame. She never revealed that she was HIV-positive—this was exposed in the press only after her death. Her family went so far as to claim that she didn’t know the nature of her own illness.

Haza had been careful throughout her career never to show any pain or hardship. We never saw her without makeup or with messy hair—she was always picture-perfect, and she did everything she could not to tarnish that image. For instance, in her last TV interview before her death, Haza gave a video interview instead of coming to the studio. The audience was told it was because she was in London, but the truth was that she was at home, too sick to leave. She hid her illness to the very end and even refused to go to the hospital out of fear that people would find out about it. Instead, she was treated at home by a doctor friend.

The nature of Haza and Ashkenazi’s relationship has been the subject of scrutiny and speculation. Some say it was a beautiful love story, while others accuse Ashkenazi of abuse and allege that Haza swapped Aloni’s domineering ways for her husband’s. Haza’s family blamed Ashkenazi for her death, and the moment she died, bitter courtroom battles regarding her inheritance ensued.

The popular assumption was that she was a virgin when she got married. That was the expectation for a woman of her background—a ludicrous one, given that Haza was a 40-year-old pop star. Nevertheless, members of her family held on to this assumption as it helped them claim that Ashkenazi was the one who gave her AIDS. The media, too, claimed at the time that her husband infected her with the disease, and Aloni later alleged the same in his book. One of the nastiest rumors was that Ashkenazi hid the fact he was HIV-positive from Haza when they wed and then infected her.

Others believe Haza was the one who caught the virus abroad, before getting married, and that she infected her husband. Shai Ashkenazi, her husband’s adopted son, loved her dearly. In a TV interview he gave on the 10th anniversary of her death, he said what a wonderful mother she was to him. He also said that he believed that they both were HIV-positive before they met and that was what brought them together. In another interview, he said that he believed his father committed suicide because he couldn’t go on living without his beloved Ofra.

After her death, it became clear that Haza wasn’t as innocent as we’d been led to believe. There are three sensational, very personal, and somewhat unseemly questions that Israelis who grew up with the myth of Ofra Haza remain curious about to this day: How did she get AIDS? Did she have any romantic or sexual relationships before she met her husband? And did she have an affair with her longtime manager, Bezalel Aloni? Except for one musician who claims he was her boyfriend early on and had sex with her, no one has yet produced more than hearsay on any of these matters.

A three-part Israeli documentary called Ofra, directed by Dani Dothan and Dalia Mevorach and broadcast in 2020, tried to untangle the enigma of the singer, but ultimately left more questions than answers. The series explores Haza’s strange relationship with Aloni, who refused to participate. Haza moved in with Aloni and his wife and kids when she was 14, and he was her manager and mentor for most of her life. Even though the documentary doesn’t expose anything unsavory, we are all familiar with horror stories of relationships between teen stars and their managers, and are left to assume the worst. Even if nothing sexually untoward happened, however, the narrative that emerges from the documentary is bad enough. According to the people interviewed, Aloni isolated Haza from the world, molded her image, denied her any kind of social life, and controlled every aspect of her career and personal life. A female friend and producer who worked with her at the height of her fame tells an anecdote of how she took Haza out to a club in Tokyo with Grace Jones. Haza was shocked to see Jones party freely without fearing what people would think, and was scared that Aloni would find out she went to a club. She was over 30 at the time.

Be this as it may, the documentary still paints her as something of a feminist icon. Haza may have been controlled by men, but in her own way she was still a rebel, having broken free of the family expectations she was born into. Instead of getting married at a young age, having children and being a housewife like she was supposed to, she followed her passion and she did what she loved, achieving a very impressive international career. And while we may not know who she really was, her roots and heritage always proudly showed through. Ultimately, we are left with her songs, her voice, and her radiant smile—which should be more than enough.

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.