In his work on the laws of teshuva, Maimonides outlined a three-step how-to guide for sinners soliciting forgiveness: abandon the sin, regret it, and accept a different future path. The twelfth-century philosopher’s target audience was individuals, not art museums. But since the latest exhibition at Chicago’s Spertus Museum opened just days before the High Holidays, it’s worth asking how, if at all, this museum might repent for its decision earlier this year to shut down a show of ancient and contemporary interpretations of maps by Israelis and Palestinians.

Spertus closed “Imaginary Coordinates,” which included both metaphoric and naturalistic maps of the Holy Land by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, on June 20, 80 days ahead of schedule, since “parts of the exhibition” were out of line with “aspects of [its] mission as a Jewish institution and did not belong at Spertus,” according to a museum release. In a conference call with the press that day, Spertus trustee Philip Gordon insisted, “This has nothing to do with censorship.” Howard Sulkin, president of the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, said of the developing news stories about the closed exhibit, “We would like to believe that there will be just a blip about that.”

To follow this show, Spertus could have opted for something tame—shtetl scenes by Chagall or colorful Agam designs—but instead it opened “Twisted Into Recognition: Clichés of Jews and Others,” an exhibit which was co-organized by the Jewish Museum Berlin and the Jewish Museum Vienna. “Twisted” is not as edgy as its predecessor—it has neither videos of a nude woman twirling a barbed-wire hula hoop while standing on Israel’s border, nor a driver asking ultra-Orthodox Israeli pedestrians for directions to the Palestinian city of Ramallah—but it is controversial in its own right, with works like Jen Taylor Friedman’s Barbie doll wearing a tallis and tefillin (Tefillin Barbie), and an installation of sculpted and painted noses by Dennis Kardon (49 Jewish Noses).

Tamir Lahav-Radlmesser’s installation includes samples of pubic hair he collected from friends and acquaintances in response to a 1939 exhibit that Josef Wastl, the Nazi curator of the anthropology department at the Vienna Museum of Natural History, created to demonstrate the racial inferiority of Jews. Wastl’s exhibit included plaster casts of faces and pubic hair taken from 500 “stateless Jews” who were subsequently sent to concentration camps.

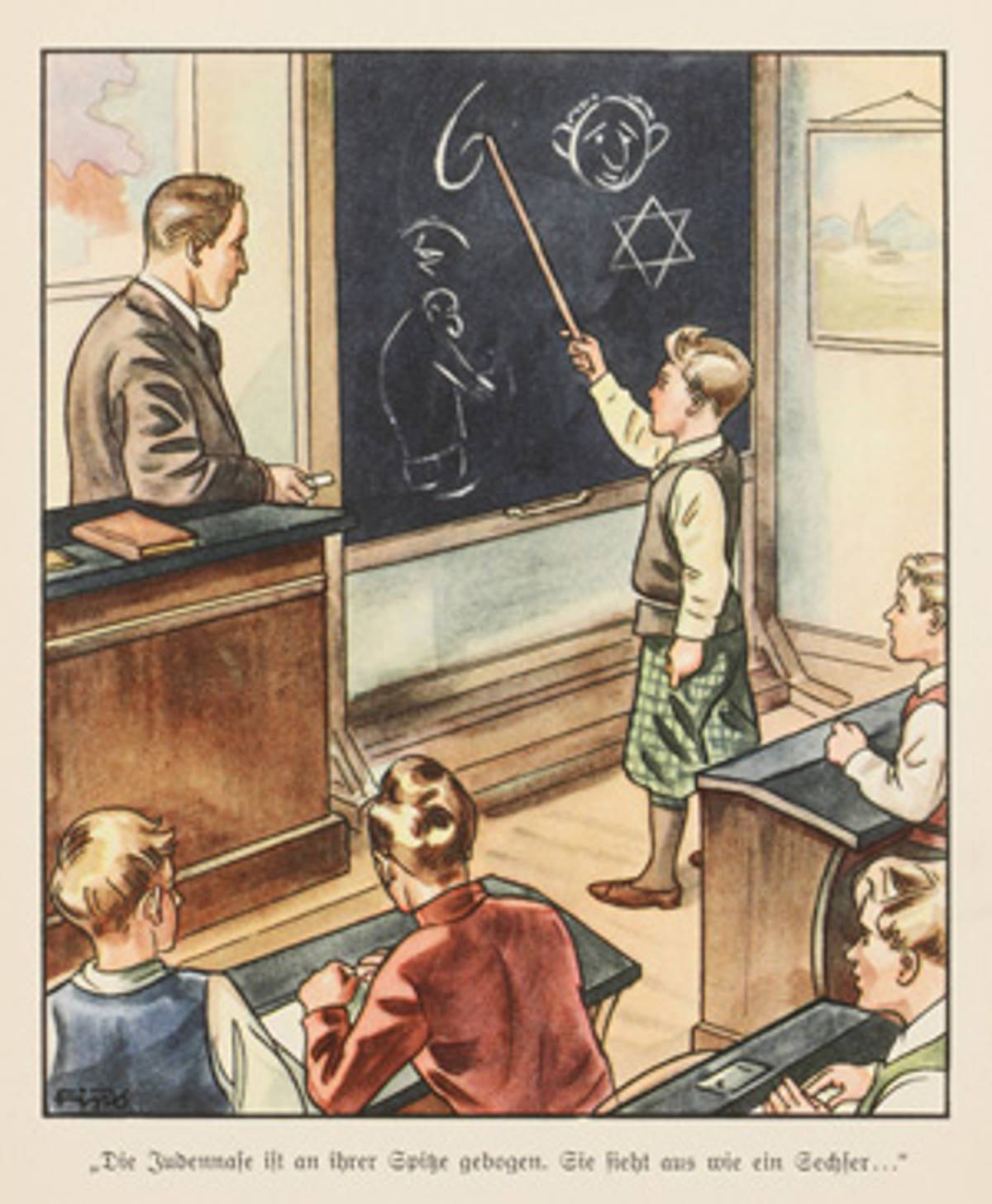

Perhaps the most controversial work in the exhibit is Der Giftpilz: ein Stürmerbuch für Jung und Alt (“The Poisonous Mushroom: an SS book for Young and Old”), a classroom textbook by Ernst Ludwig Hiemer which had a 1938 print run of 60,000. The Spertus exhibit shows an illustration from the book of four schoolboys, matching parts in their blond hair, looking on with their teacher as a fifth student holds a pointer to a blackboard that features chalk drawings of a Star of David, a hunched man who might be the wandering Jew, and the number six. The caption explains the last symbol: “Die Judennase ist an ihrer Spitze gebogen. Sie sieht aus wie ein Sechser,” or, “The Jewish nose is bent at its peak. It looks like a six.”

Spertus hopes the show will be “stereotype-busting,” and its release assures (perhaps both viewers and board members) that the show “does not intend to deny regional, ethnic, or cultural differences. Rather it explores how stereotypes about these differences are conveyed through images and objects, some of which communicate difficult or even brutal messages.” Yet most reviewers aren’t buying it, nor do they seem ready to forgive and forget the “blip.”

Manya Brachear’s review in the Chicago Tribune called “offending Jewish sensibilities” Spertus’ “new stock in trade,” and quoted Beth Gelman, the museum’s director of education, as saying that she expected some people to be offended, because “learning questions our assumptions.” Time Out Chicago’s Lauren Weinberg began her article with a discussion of the censored show, which she hailed as challenging and beautiful, before panning “Twisted” for being “so rigid that it doesn’t leave much room for surprises.” She wondered why Spertus’ show about stereotypes did not mention the museum’s own censorship.

Weinberg is surely aware that it is rare for any museum, let alone one funded by the Jewish United Fund/Jewish Federation, to criticize itself in its own exhibit, but she might be on to something in her critique that the show does not even attempt to respond to stereotypes of Israelis. She also questioned why there are “zero mentions of Palestinians” among the clichés of “others” included in the show: The only Muslim representative is Women of Allah: Rebellious Silence, a photograph of a woman wearing a headscarf and holding a gun in front of her face, which is covered with Arabic writing. The photograph was taken by Iranian artist Shirin Neshat, whose work also appeared in “Imaginary Coordinates.”

As for a question Weinberg did not ask: Why doesn’t “Twisted” tackle stereotypes of Jews by Jews? If the museum really wants viewers “to closely examine stereotypes and clichés, and to reflect on them and discuss them,” wouldn’t it have been fascinating if the show included ads from the Yiddish press at the beginning of the twentieth century which were designed to assimilate Eastern European immigrants? What about cartoons from Jewish newspapers, in which Jews of one denomination denounce other types of Jews? Showing nineteenth-century walking sticks with noses that double as handles, which were later appropriated as anti-Semitic objects, is an important and ambitious move for a Jewish museum, but an institution that is quick to expose others’ stereotypes might try interrogating and exposing its own biases.

The subtitle of “Twisted” promises that the exhibit will explore not only Jews, but “others.” Instead of examining the philosophical and psychological processes of interacting with (and often forming stereotypes of) “the Other,” Spertus narrowly defines “others” simply as non-Jews. Had “Twisted” taken a closer look at the Jewish community, it would have had to address the fact that Jews are hardly homogeneous, and that members of one denomination often see Jews of different nationalities or levels of religious observance as “others,” too.

Before it tries to repent, Spertus needs to identify exactly where it fell off track. Steven Nasatir, president of the JUF/Jewish Federation in Chicago, told the Tribune that “Imaginary Coordinates” was “clearly anti-Israel” and that he was “very surprised” and “saddened” that a Jewish institution would host such an exhibit. Michael Kotzin, executive vice president of the same organization, added that a Jewish museum is the “last place the Jewish community should hear echoes” of anti-Israel sentiments. But if museums should avoid edginess and provocation, one wonders what venues the American Jewish community has set up to hear constructive feedback and new ideas.

Luckily the Jerusalem Post’s Marilyn Henry elevated the discussion with her observation that the censorship “inadvertently performed a great communal service: It opened the door to a long-overdue discussion on the role of American Jewish museums.” Henry recommended that angry viewers either close their eyes or go home. “I, for one, do not see the geopolitical balance of the Mideast shifting because an American Midwestern museum exhibits its map collection,” she wrote. Instead, Henry sees American Jewish museums as “cultural sanctuaries,” which “may be the only open Jewish space in the U.S. where traditional, ethnic, and disengaged Jews can meet with each other and with the larger community.”

Nasatir and Kotzin seem to think of Jewish museums as mirrors that ought to reflect what the community already believes, while Henry sees their potential to look forward. This is surely a struggle for all museums—not just Jewish ones—as they try to prove that their mandate as educational institutions necessitates some pushing of the envelope. Being on the vanguard does not just mean filling an exhibit with pop culture symbols like Tinky Winky (the allegedly gay character from Teletubbies), Aunt Jemima, and Michael Jackson, as “Twisted” does. It is refreshing to see Monty Python’s comical Life of Brian beside Franco Zeffirelli’s sobering Jesus of Nazareth, and Al Pacino’s performance as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice in an exhibit that also includes Howard Zieff’s ad campaign, You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s, which shows a Native American man with braids and a feather also wearing a black hat and holding a deli sandwich. But this subject begs for more than just clever juxtapositions of art and kitsch.

With “Twisted,” Spertus had an opportunity to distinguish itself from other Jewish museums, becoming self-conscious and thus vulnerable. Instead, it settled for being just another PR voice for American Judaism, piling up even more evidence that Jews are marginalized and oppressed. Until it manages to grapple more fully and honestly with the provocative topics it raises so promisingly, it will be hard to treat the museum as much more than a $55-million building with a great view of Lake Michigan.

Menachem Wecker is a writer based in Washington, D.C. He blogs about religion and the arts at Iconia.

Menachem Wecker is a writer based in Washington, D.C. He blogs about religion and the arts at Iconia.